-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2015; 5(1): 32-38

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20150501.06

Prevalence and Response to Occupational Hazards among Nursing Students in Gaza Strip, Palestine: The Role of Personal Protective Equipment and Safety Regulations

Ashraf Eljedi

Faculty of Nursing, Islamic University of Gaza, Gaza Strip, Palestine

Correspondence to: Ashraf Eljedi , Faculty of Nursing, Islamic University of Gaza, Gaza Strip, Palestine.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Although nursing students are more prone to occupational hazards and injuries in the course of their clinical training activities, they have not been the primary focus of any published study of exposure incidents in Gaza strip, Palestine. The aim of this study was to describe the prevalence of exposure to occupational hazards among nursing students and to determine the degree to which occupational safety and health control strategies are applied. A cross sectional descriptive study was conducted at the faculty of nursing in the Islamic University of Gaza, Palestine. The results from 114 respondents showed that 44.3% were exposed to at least one of the occupational hazards. Exposure to psychological hazards was the highest (56.6%) followed by accidental hazards (44%), chemical hazards (43.9%), and biological hazards (39.8%), while the lowest was the physical hazards (39.3%). Needle-stick injuries when using sharp devices were reported by 45.5% of the students. About 67% were exposed to verbal or physical abuse while 43.0% were exposed to the x-rays and other types of radio-graphical procedures. Irritation of skin, eyes and nose was quite prevalent among students (48%) due to exposure to hazardous chemical substances. Although most of the participants (97.4%) were fully aware of using Personal Protective Equipment and safety regulations, only 25% were actually compliant. In conclusion, most of the nursing students were exposed to at least one of the five occupational hazards. It is important therefore to continuously encourage behavioral changes, promotion of safety measures and application of occupational health services to minimize workplace-induced injuries.

Keywords: Hazard Exposure, Occupational Hazard, Safety Regulations, Nursing Students, Palestine

Cite this paper: Ashraf Eljedi , Prevalence and Response to Occupational Hazards among Nursing Students in Gaza Strip, Palestine: The Role of Personal Protective Equipment and Safety Regulations, Public Health Research, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 32-38. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20150501.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- It is widely acknowledged that nurses are a crucial component of the healthcare system. They are an integral part of clinical services and have primary responsibility for a significant proportion of patient care in most healthcare settings [1]. Nurses are prone to occupational hazards and injuries in the course of their day to day activities in the health care settings [2]. Given the nature of nursing working environment, responsibilities and duties, nurses are on the frontline of numerous occupational hazards such as biological/infectious disease, chemical risks, environmental/ mechanical risks, physical risks, and psychosocial risks [3-6]. The safety of nurses from workplace-induced injuries and illnesses is important to nurses themselves as well as to the patients they serve. The presence of healthy and well-rested nurses is critical to providing vigilant monitoring, empathic patient care, and vigorous advocacy. Although nurses are known to be a high-risk subgroup for these events, nursing students may be at even greater risk due to their limited clinical experience [7]. According to a British study, nursing students have not been the primary focus of any published study of exposure incidents, and nursing students were twice as likely to experience a sharp-related injury as "trained" nurses [8].In Gaza strip, nursing schools have increased from one to five institutes in the last decade and offered many degree programs. Unfortunately, no previous study was conducted in Gaza strip to tackle this serious issue. All of the studies have focused on the occupational hazards experienced by the registered health care workers in the Palestinian health institutions. Therefore, this study aimed to focus on the occupational hazards that nursing students may face during their training period and the preventive measures they use to protect themselves and their patients.

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Needle-stick Incidents (NSIs)

- Of all healthcare workers, nurses are at most risk of needle-stick incidents. In fact, nurses tend to be exposed 4.27 times more often than physicians [9]. A study in Pakistan revealed that in addition to very high rates of NSIs, low safety practices including inadequate vaccination coverage, unavailability of infection control guidelines and other preventive facilities were reported [10]. Other studies found that injuries from contaminated needles and other sharp devices used in healthcare settings have been associated with transmission of more than 20 different blood borne pathogens to nurses such as hepatitis B and HIV [11, 12]. In Gaza strip, a study conducted by Eljedi reported that 66% of health care workers had been injured by needles or sharp medical instruments in Gaza hospitals [13]. A hospital-based cross sectional study conducted in a general Hospital in Malaysia found that the prevalence of NSIs was 12.5% among nurses [14].

1.1.2. Musculoskeletal Injury Exposure

- The largest share of hospital injuries and accidents result from puncture wounds and injuries associated with handling heavy equipment [5]. Back injuries account for the most job-related days lost [15]. In a study by Meier [16] found that 38% of all nurses are affected by back injuries, nearly all of these injuries (98%) are due to nurses lifting and moving patients manually. Further, de Castro states ‘‘Work-related musculoskeletal disorders are the leading occupational health problem plaguing the nursing workforce’’ [17].

1.1.3. Chemical Hazards

- There are a variety of chemical hazards related to patient treatment and maintenance of a proper environment in the hospitals. As a result hospital and health care workers are thought to be the largest group at risk from these chemicals. These Substances commonly used in the health care setting can cause asthma or trigger asthma attacks [5]. In many ways, these chemical hazards appear to be the most dangerous, as it's more difficult to determine their short- and long-term effect on nurse.

1.1.4. Workplace Violence Exposure

- Compared to other healthcare workers, nurses face a higher level of risk of violence. More than 9.5% of general nurses working in general hospitals are assaulted annually [18]. Gerbrich et al. [19] reported that rates of both physical (13.2%) and non-physical (38.8%) violence are on the rise for emergency department, home/long term care, intensive care, and psychiatric/behavioral care nurses. Similarly, McPhaul and Lipscomb [20] stated that the majority of threats and assaults to nurse arise from patients.

1.1.5. Physical Hazards

- Physical hazards include fires and burns from laser beams, noise levels from technical equipment, electrical burns and fires [5], and ionizing radiation from x-rays, fluoroscopy, image intensifiers, radioactive implants and other therapeutic radiation procedures.

2. Methodology

- The primary purpose of this paper is to investigate two empirical questions: first, to determine the incidence of occupational hazards exposure in Islamic University school of nursing as reported by students during their clinical training in the health care settings; and second, to determine the degree to which occupational safety and health control strategies are applied in this accredited nursing school. To achieve these goals, a two-part, researcher-developed questionnaire was developed. Part 1 of the questionnaire collected demographic data and programmatic data for all respondents and assessing the total number of exposure incidents experienced by respondents in clinical education settings. In Part 2 of the questionnaire, the respondents were asked whether they had access to various items of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in their clinical educational settings and whether they ever had the opportunity to use various safety engineered devices. To check the validity of the questionnaire, the questionnaire was distributed in April 2012 to a group of experts with different backgrounds (Education and nursing fields) and a pilot study was carried out on sub sample of students (30 students) and accordingly some modifications were done.

2.1. Participants

- There were a total of 305 students in the second, third and fourth level in the college of nursing. Those students are distributed for training in different health institutes sectors (governmental, United Nation, and private) which include primary, secondary and tertiary levels of prevention. The questionnaire was distributed in May 2012 to 150 nursing students. They were surveyed directly after final exams to include their entire nursing student experiences and to eliminate respondent concerns that their schools of nursing would learn of non-reported incidents.

2.2. Ethical Considerations

- The ethical and administrative considerations were taken. The ethical approval and administrative permissions to perform the study were obtained from the faculty of nursing at the Islamic University of Gaza. Every participant in the study received a complete explanation about the purpose of the study. All participants signed consent forms before participation. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained all over the study period. Time allocated for filling the questionnaire was 15-20 minutes.

2.3. Data Analysis

- SPSS version 18 was used to analyze the data. Frequency and percentages were calculated for describing the socio-demographic and academic variables. Cross tabulation was conducted to determine the relationships between two variables or more. Proportions were used to rank the incidence of the hazards from highest to lowest. T-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed to compare means between groups regarding occupational hazards. P value < 0.05 was determined as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

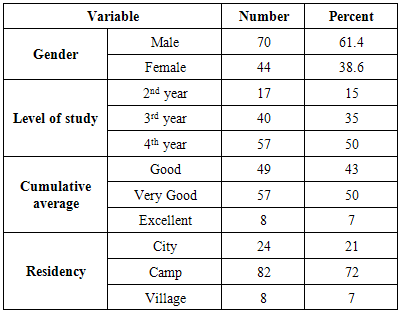

- From a group of 150 students, 114 successfully completed questionnaires were obtained (overall response rate 76 %). There were 17 students from the second year (15 % of the total), 40 from the third (35%) and 57 from fourth (50 %). Most of the respondents were male (61.4%); about 50% had "very good" cumulative average and 72% live in refugee camps in Gaza strip (Table 1).

|

3.2. Exposure Incidents

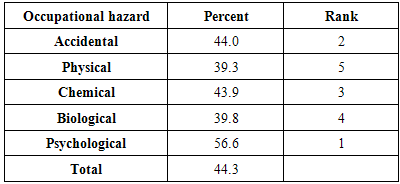

- Table 2 presented the incidence rates of the different occupational hazards that the students encountered during their clinical training in the health care settings in Gaza strip. As it is presented in the table, exposure to psychological hazards was the highest followed by accidental hazards, chemical hazards, and biological hazards, while the lowest incidence rate was the exposure to the physical hazards. About 44.3% of the students were exposed to at least one of the five occupational hazards investigated in this study.

|

3.2.1. Accidental Hazards

- There were different exposure incidents experienced by the respondents. The most common exposure was Needle-stick Incidents (NSIs) with rate (45.5%) when using syringes and other sharp devices. The second hazard in this category was back injuries with rate (37.7 %) due to lifting and moving patients manually.

3.2.2. Psychological Hazards

- Exposure to psychological hazards among the respondents was high with rate 56.6%. About 67% experienced psychological stress while 45.3% faced a significant risk of injuries from assaults by patients or their families.

3.2.3. Biological Hazards

- The most common biological hazard experienced by the respondents was the exposure to parasites and worms when dealing with patients' skin or their secretions (41.2%). The second biological hazard was the exposure to the blood-borne diseases with rate 38.3%. However, none of the respondents infected by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV).

3.2.4. Chemical Hazards

- There were different exposure incidents to chemicals experienced by 43.9% of the respondents with symptoms ranged from dermatitis and asthma to anaphylaxis. Hazardous chemical exposure occurred in a variety of forms-including aerosols, gases, and skin contaminants-from medications used in practice. Exposure can occur on an acute basis, up to chronic long-term exposures, depending upon practice sites and compounds administered; primary exposure routes were pulmonary and dermal. About half of the participants (48.0%) reported frequent irritation in their eyes, skin and nose due to the inhalation of chemical particles, touching disinfectants and contaminated materials and splashes of irritating fluids. Allergic reaction to Latex was reported by 43% of students which ranges from mild redness of the skin to severe itching and irritation.

3.2.5. Physical Hazards

- About 43.0% reported that they were exposed to the x-rays and other type of radiographical procedures during clinical training either in the radiology departments or in other hospital settings.

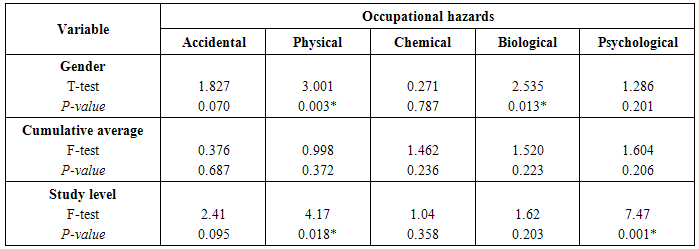

3.2.6. Occupational Hazards and Socio-Demographics

- To measure significant differences between the study variables (gender, level of study year and cumulative average) and exposure to occupational hazards, we used T test and one way ANOVA analysis. According to table (3), there are significant differences between male and female students in regards to the exposure to physical (P=0.003) and biological hazards (P = 0.013). Male students were more exposed to these two hazards than females (Physical: Mean for male = 2.51 and for female = 2.11; Biological: Mean for male = 0.794 and for female = 0.446). Moreover, there are significant differences between the level of study and both psychological hazard (P=0.018) and physical hazard (P=0.001) in favor to students in fourth-year level because students at level four spend more time in the training in the hospital than other students in the college. However, no significant differences were found between cumulative averages and the incidence of the occupational hazards (P-value ≥ 0.05).

|

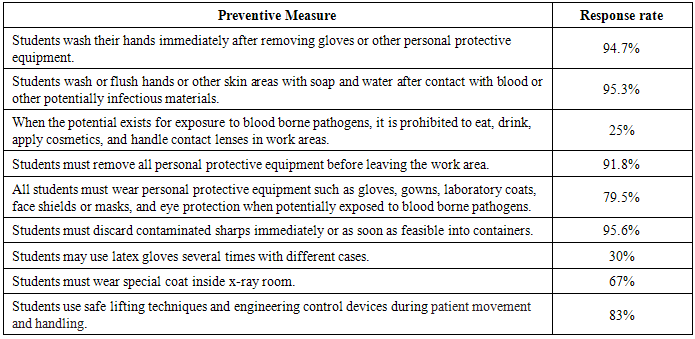

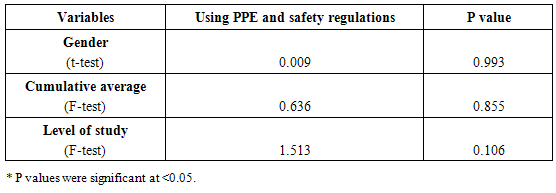

3.3. Using Personal Protective Equipment and Safety Regulations

- Although almost all respondents recalled access to latex/vinyl gloves with rate 97.4% during their clinical educational experiences, 30% of the students used latex gloves several times with different patients. When respondents were asked whether they ever had the opportunity to use other safety devices during their student clinical experiences such as goggles, coats and surgical masks, 79.5% of respondents recalled the use of coats during collecting blood samples and 67% of respondent were wearing special coat in x-ray room. About 95.6% of the students confirmed that they used standard methods when they deal with medical wastes. Most of the students (83%) are fully aware of using good body mechanics and engineering devices during positioning and transferring patients to prevent muscle strains (Table 4).

|

|

4. Discussion

- In this study, most of the respondents were male with "very good" cumulative averages. There were 15% sophomores, 35% juniors and 50% senior students. About 72% live in refugee camps in Gaza strip. It was very interesting in this study to indicate that exposure to psychological hazards was the highest among all occupational hazards for nursing students. This could be explained by the fact that Gaza strip is a very poor area in which the hospitals suffer from severe shortages in infra-structure, equipment, supplies and human resources. This made the students to feel that they were unable to provide the best level of care for their patients. Moreover, recurrent wars in Gaza with their overwhelming burden on hospitals developed feelings of helplessness and hopelessness among students. However, such results are in opposite to many studies in which physical risks were the most common hazards reported by registered nurses and nursing students [21, 22].The exposure to needle-stick injuries (NSIs) was the most common (45.5%) in the accidental category. This finding is strongly supported by the researches cited concerning (NSIs). The NSI prevalence rate among nursing students in other countries seems to vary widely [23]. For example, Yassi and McGill found that 12% of their students working in a large medical center had an NSIs [24]. Among Chinese nursing students, the NSIs rate was around 32% [12] compared to 9% of Taiwanese nursing students [25] and 15% of Italian nursing students [26]. However, a study conducted in Gaza strip to evaluate the compliance of HCWs with the universal safety precautions found that 66% of health care workers had been injured by needles or sharp medical instruments in Gaza hospitals [13]. This indicated that not only the students in Gaza strip but also the registered HCWs are at higher risks for blood-borne diseases because of the high incidence of the NSIs. In spite of high prevalence rate of NSIs in our study, none of the respondents infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV); students' immunization against vaccine-preventable diseases such as HBV before clinical training was a very important protective factor against this infectious disease. The second hazard in this category was back injuries (37.7%) due to lifting and moving patients manually. These findings are consistent with previous research where occupation-related back pain affected 38% of nurses in USA. At the same time, 12% of those affected were thinking of leaving nursing because of back pain [5].In the psychological category, about 67% of the students experienced psychological stress due to the nature of nursing profession which requires spending long time with people who are suffering, working with unconscious clients and caring for dying patients. Moreover, work at night (between 9 pm and 8 am) and rotating shifts (shifts that change periodically from days to evenings or nights) lead to long-term insomnia and excessive sleepiness and inability to adapt sleep hours adequately on these shifts. Furthermore, 45.3% also faced a significant risk of injuries from assaults by patients or their families. Those who were carrying weapons in emergency departments in Gaza strip (due to political instability) created the opportunity for severe or fatal injuries. This finding is strongly supported by other studies concerning psychological hazards. In a survey of more than 43000 nursing personnel in five countries, 17–39 percent planned to leave their job in the next year due to physical and psychological demands [5]. It was reported that rates for both psychological (38.8%) and physical (13.2%) violence are on the rise for emergency department, home/long term care, intensive care, and psychiatric/behavioral care nurses [19]; and most of these threats and assaults to nurse arise from patients [20].Regarding using Personal Protective Equipment and safety regulations, it was clear that most of the students were fully aware of safety regulations; however, there was noncompliance in some areas such as eating, drinking, applying cosmetics, and handling contact lenses in work areas when the potential risk exists for exposure to blood-borne pathogens. Such finding confirms that knowledge of occupational safety precautions does not necessarily impact compliance [14, 27]. This study also revealed no significant differences in using PPE based on gender, cumulative average and level of study; this may be due to the fact that all students received strict instructions and close supervision about appropriate and effective use of PPE.

5. Conclusions

- This study indicated that there are several key areas of concern existing within field settings that linked with incidents and accidents. These factors included biological / infectious disease, chemical exposure, environmental / mechanical hazards, physical risks and psychosocial risks. Furthermore, it was important to include both accidents and incidents when dealing with these concerns because it is in these "incident" situations where the potential lies for accidents to occur.The frequency of exposure incidents in this study revealed the potential for nursing student's acquisition of life-threatening hazard infection. The discovery that most of these exposure incidents were potentially preventable by using existing safety-engineered devices and routine safety practices provides a mandate for nursing education. Nurse educators must ensure that students are knowledgeable about mechanisms of disease transmission, and different type of occupational hazards and the safety regulation. Nursing students need to know the characteristics and benefits of safety engineered devices so that they value them and lobby for their use when they enter practice environments. Nurse educators must also educate health care administrators about studies documenting device efficacy. A safe practice environment for nursing students and also for practicing health care professionals may depend on their actions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- We would like to express our gratitude to all students in the college of nursing at the Islamic University of Gaza who participated in the study. Many thanks also go to the academic and administrative staff at the college for their cooperation and assistance. Their sincere contributions made this research fruitful and possible.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML