-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2015; 5(1): 16-23

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20150501.03

Strengthening Health Systems and Interventions towards Quality Maternal Care: A Focus on Millennium Development Goal Five

Robert Bella Kuganab-Lem1, Rhubamatu Iddrisu, Issahaku Must2

1University for Development Studies, Department of Allied Health Sciences, School of Medicine and Health Science, Tamale, Ghana

2University for Development Studies, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Science, Tamale, Ghana

Correspondence to: Robert Bella Kuganab-Lem, University for Development Studies, Department of Allied Health Sciences, School of Medicine and Health Science, Tamale, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In Africa South of the Sahara, lots of women die during pregnancy and childbirth largely due to lack of access to skilled routine and emergency care. There is consensus that a well functioning health system is imperative in providing quality maternal care to reduce maternal mortality. This study sought to assess the quality of maternal health care delivery in the Tamale metropolis of Ghana. It was a descriptive cross-sectional survey; probability proportional to size was used to select participants. The study samples were made up of 390 women of child bearing age who attended the health facilities and 75 health personnel in five facilities. Two focus group discussions were also held in two randomly selected communities of the metropolis. The key findings were that there was general client dissatisfaction. This was expressed in long waiting time, dirty environment and unfriendly staff attitude. 88.7%, 41.3% and 60.5% expressed dissatisfaction with the waiting time, dirty facility environment and unfriendly staff attitude respectively. The study also found that very critical and important materials such as emergency drugs and blood were in short supply. 54.8% of respondents who went on emergency admissions could not get emergency drugs at the facility and 82.2% who needed to be transfused could not be transfused immediately because blood was not readily available. The numbers of Health personnel were found to be inadequate. They had little or no refresher training in dealing with emergency maternal health care issues. The study concludes that given this situation in a metropolis, makes the achievement of MDG five a long shot, particularly In Ghana where majority of the population live in rural and underserved communities.

Keywords: Health systems, Quality Maternal Care, Millennium Development Goals

Cite this paper: Robert Bella Kuganab-Lem, Rhubamatu Iddrisu, Issahaku Must, Strengthening Health Systems and Interventions towards Quality Maternal Care: A Focus on Millennium Development Goal Five, Public Health Research, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 16-23. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20150501.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The issue of quality maternal health care has become critical since the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Quality health care means providing health services to individuals and communities to improve their health outcomes. It is usually focused on client’s perspectives on satisfaction and on achieving efficiency in health care facilities [1]. The provision of quality health care hinges on a well functioning health system. Health Systems are often referred to as all the activities whose primary purpose is to promote, restore or maintain health [2]. It is the identification of issues that interfere with the provisions of quality services and introducing system changes that result in sustainable improvements in health that is referred to as Health System Strengthening [1, 2]. The WHO defines maternal health as the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period. Maternal Care includes antenatal care (ANC), care during delivery, intranatal care (INC) and care of mother for 42 days after delivery, postnatal care (PNC). Many Countries including Ghana have tried over the years to introduce arrays of initiatives and strategies to improve the functions of the health system to lead to better health. These initiatives are often aimed at improvements in access, coverage and quality of care, especially maternal care.Quality is the degree to which a product or service meets the expectation of an individual or a group [3]. Whilst there is no universally-accepted definition of "quality care", it is widely acknowledged to embrace multiple levels from patient to health systems and multiple dimensions, including safety as well as efficiency. Quality care as noted by [4] should lie at the core of all strategies for accelerating progress towards MDG Four and Five. They [1, 2] observed that quality maternal health care implies the extent to which maternal health care resources and services correspond with standards of a particular country. However, to provide quality maternal health, health care providers need to have adequate infrastructure, clinical skills, necessary equipment and supplies and a functioning referral system so that women with complications can get treatment as soon as possible. Successful prevention of maternal deaths hinges on adequate and quality emergency obstetric care. To achieve this quality emergency health care is having skilled health care personnel, a supportive environment in terms of essential drugs and supplies, adequate equipment in quality and quantity and a good referral system. Many household surveys report a reasonably high proportion of women delivering in health facilities. However, the quality and adequacy of facilities and personnel are often not assessed [2].The World Health Organization issued guidance in 2001 on a new model of antenatal care (ANC) called focused antenatal care (FANC). Ghana adopted this and reinvigorated antenatal care services. Three major interventions were adopted and vigorously implemented. These were; using focused antenatal care job aids (charts and posters). Implementation of integrated services, which includes history taking, physical and laboratory examinations and ensuring that the same provider attends to the client during all antenatal care visits which was reduced from 13 to four comprehensive visits. In 2008 the government added a benefit package of free maternal care for pregnant women. The Benefit Package includes the following; free registration or renewal of membership of the National Health Insurance; no processing fee for registration or renewal and also no maturity period for an insurance cover [5].Making antenatal care attendance comprehensive and personalised and removing the financial barriers were ways to improve access to quality maternal health care in public and private health facilities. [6] Assert that regardless of continued high-level political and organizational commitments, maternal mortality and for that matter quality maternal health delivery remains as one of the greatest challenges facing the developing world, as well as a tragedy that is often neglected or compromised. To them, the progress on the maternal mortality reduction target has been far too slow to reach the set goal, a sad reality that many view as one of most embarrassing manifestation of health and social systems failure.In Ghana even though over 90% of pregnant women attend antenatal care in health institutions, only 43% deliver in health facilities [7]. The national caesarean section rate stands at 3.7% and this reflects inadequate obstetric coverage for maternal health set in MDG Five [8].Several reports suggest that reducing maternal mortality and reaching the MDG Five target by 2015 is difficult for Ghana. The question therefore is what is the challenge in the provision of quality maternal health services in Ghana and particularly for a metropolis, given interventions to improve the health system for maternal health care delivery?

2. Methodology

- Tamale Metropolis is one of the twenty six administrative and political Districts in Northern Region and is the capital town of the region. It is located in the centre of the region, approximately 175km east of longitude 1° west and latitude 9° north. The Metropolis has a total population of 371,351 projected at 2.9% regional growth rate. Population of WIFA is Ninety Three Thousand One Hundred and Forty Five (93,145) and expected deliveries 15,525 [10]. It has a surface area of 1011 sq. km. which forms about 13% of the total land area of the Northern Region. Its population density is 384 persons per sq. km [7, 9].This study was a Descriptive Cross-sectional survey. The study population were all women in the Tamale Metropolis and health personnel at five selected hospitals and clinics. The study sample included pregnant or women with children who attended child welfare, antenatal and post natal clinics in the Metropolis (390) and Midwives, Nurses and Doctors working in the health facilities (75).Quantitative data was gathered using questionnaire administered to the women who attended the five health facilities, whiles qualitative data were gathered from in-depth interviews with staff of the maternal health units of the facilities and two focus group discussions in two randomly selected communities. The dependent variable for the study was quality maternal health care measured by client satisfaction and outcomes while independent variables were; Staff-Client interpersonal relationship including levels of therapeutic communication and attitudes, Adequacy and quality of staff, Available resources in health facility and Client satisfaction.

3. Data Analysis and Results

- A set of questionnaire was administered to 390 respondents at three public hospitals, a private hospital and a maternity home in the Tamale Metropolis. An in-depth interview was also conducted for Nurses, Midwives and Doctors. Two focus group discussions were also conducted in two communities. Data were processed and analyzed using SPSS version 17. The data analyzed are presented in tables, graphs and a pie chart. The focus group discussions were transcribed and translated and emerging themes extracted. The in-depth interviews were also analyzed manually.

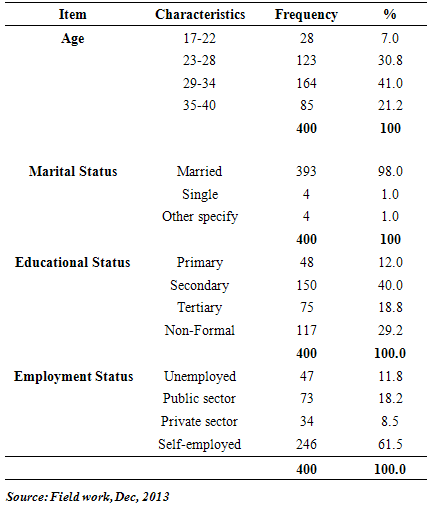

3.1. Socio Demographic Status

- As shown in the table 1, the age group of study participants ranged from 17 to 40 years. 41% were between the ages of 29 to 34 years. A huge majority of the respondents, 98% were married. Only 1% of the respondents were single and another 1% were either divorced or separated. 12% of the respondents had primary education, 40% had secondary education whiles 18.8% had tertiary education. 29.2% did not have formal education. 11.8% of the respondents were unemployed. Respondents on public sector employment were 18.2%, 8.5% were employed in the private sector. A good majority of the respondents, 61.5% were self-employed.

|

3.2. Client Satisfaction

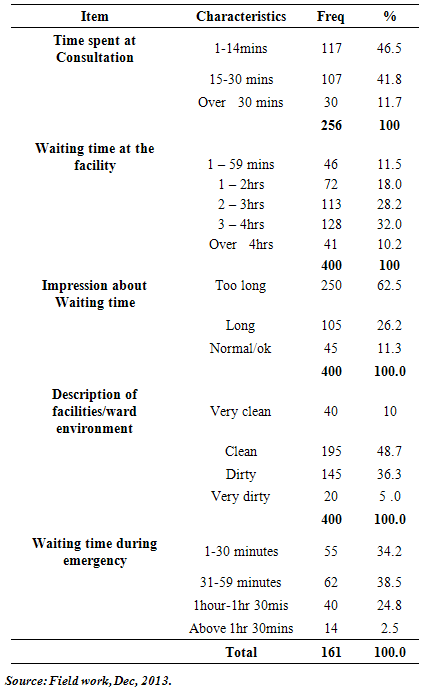

- Waiting time at the facilities was averagely high. 11.5% of the respondents waited for one to 59 minutes. 18% waited for one to two hours, 28.2% waited for two to three hours. Respondents who waited for three to four hours constituted 32% whiles 10.2% said they waited for over four hours to be seen by the care giver. Asked about the time respondents spent with the provider during consultation, 46.5% of respondents spent one to 14 minutes, 41.8% spent 15 to 30 minutes and 11.7% said they spent over 30 minutes.Asked about their view on the waiting time, 62.5% felt the waiting time was too long, 26.2% felt it was long. Only 11.3% felt the waiting time was normal.The waiting times for those who visited during emergency were; 34.2% for one to 30 minutes, 38.5% waited for 31 to 59 minutes and 24.8% waited for one hour to 30 minutes. The rest of the respondents who waited for over one hour 30 minutes constituted 2.5%. Respondents impression about the facility/ward environment was fair.10% said the environment was very clean, 48.7% reported it was clean, 36.3% indicated that the ward environment was dirty and 5% said it was very dirty.On the issue of if respondents were generally satisfied with services received at the facilities, 52.5% were generally satisfied and 47.5% said they were dissatisfied with the services of the facilities.

|

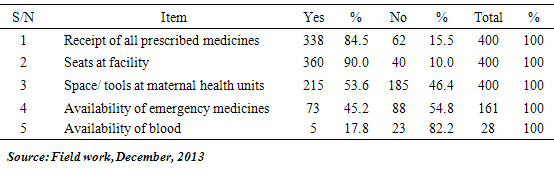

3.3. Material Resources

- Majority of the respondents got their prescriptions at the same health facility, 84.5%. Only 15.5% did not receive all the prescribed drugs at the same facility. On the availability of drugs, staffs interviewed and the focus groups were agreeable that routine medications were always available in the dispensary.Table 4 above depicts responses on availability of material resources at the facilities. On availability of space and tools, 53.6% of the respondents indicated that there were sufficient tools and space at the facilities. Majority of respondents got seats at the facility (90%). Equally, the focus groups were of the view that there were sufficient basic tools and space. In the in-depth interviews, staff noted that basic material supplies were adequate except that the supplies at times were erratic.

|

|

3.4. Human Resources

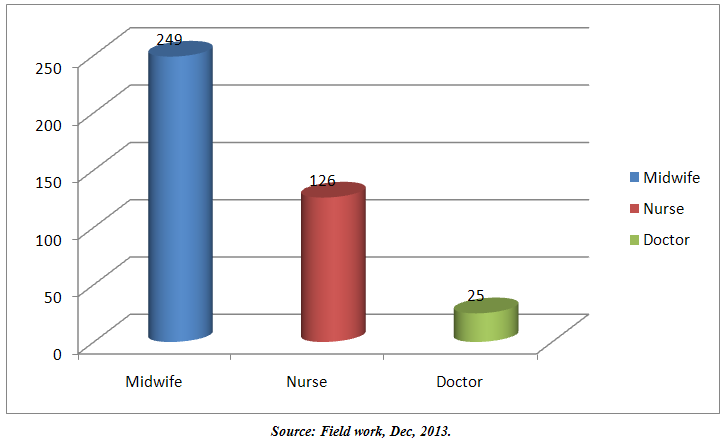

- 62.4% of the respondents when asked about the category of health personnel who attended to them mentioned a midwife, 31.5% mentioned a nurse and 6.1% said that a doctor attended to them. 53% of respondents thought that health staffs were not adequate to deliver maternal health services where as 47% thought health personnel were adequate.On the adequacy of the health staff, majority of FGD participants were of the view that they are inadequate. They intimated that their inadequacy sometimes cause them to have long waiting hours at the facility.The health staffs were of the view that their numbers were inadequate. At the West Hospital, only two doctors attend to all clients including maternal health cases. At the ANC, only five staffs attend to an average of 70 clients daily. At the Central hospital, five staffs attend to 85 clients daily. At the private clinic, it was noted that one doctor (part-time) and a nurse or midwife attend to the clients. Most often in situations of emergency, the Doctor has to be called from somewhere.On staff quality, it was noted that majority of staff from all the study facilities have not had any refresher training for over three years. The few who have had training had it once over the last three years.

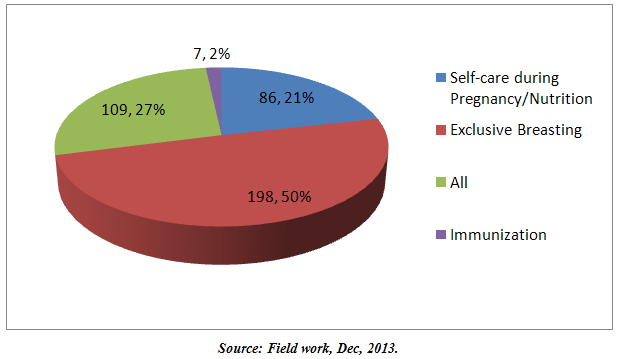

| Figure 1. Education and Counseling |

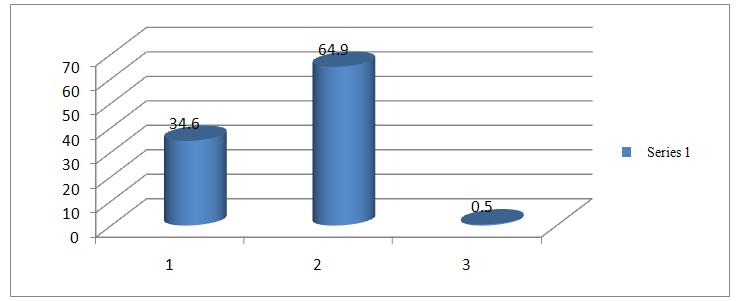

| Figure 2. Laying place at last delivery |

| Figure 3. Human Resources |

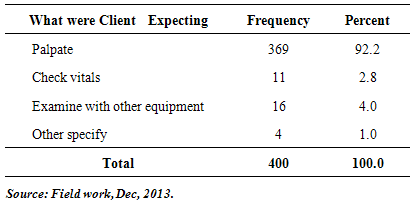

3.5. Client Expectations of Services and Communication

- An overwhelming majority of the respondents, 92.2% indicated that they were expected to be palpated during any visit to a health facility. 2.8% expected their vital signs to be checked whiles 4% of the respondents’ expected that they should be examined with some equipment. When respondents were asked whether there was sufficient communication between them and the health care professionals, 35% indicated that there was sufficient communication and 65% of the respondents said there was little or no communication at all on findings/ results of palpation, vital signs or any other assessment done by the health professionals.This statement was typical amongst the focus groups.“they do not communicate with us. the only word you hear is go and take this medicine.” On whether respondents were welcomed at the point of delivery of service either in consulting room, labour/maternity wards or at ANC, 39.5% said they were welcomed and 60.5% said they were not welcomed.On whether staff had the right attitude, 58.7% of respondents indicated that staff were unfriendly and displayed bad attitude where as 41.3% said they were friendly, caring and showed good attitude.

4. Discussions

4.1. Client Satisfaction

- Client satisfaction was measured in respect of waiting time, the facility environment, availability of toilets, consultation time and expectation of services. A study in Nigeria reported that the national mean waiting time before antenatal consultation was 131.1 minutes [10]. This national average for Nigeria is in consonance with this study were the mean waiting time is 130 minutes. A study to determine the average waiting time in a Malaysian public hospital and to gauge the level of patient satisfaction also found that on average, patients waited for more than two hours [11]. Majority of the women intimated their frustration when they go to the clinics or hospital due to the long periods of time they have to spend. For them, more than one hour of wait was dissatisfying. A common remarked was; “any time I have to go to the health facility especially for antenatal or postnatal, I feel sad because I will not be able to do any work that day because by the time I come back, it is too late for me to prepare food and go out to sell”.It has been well documented that overall satisfaction declines the longer a patient has to wait in a health facility. Patients experience extreme inconvenience and negativity if they have to wait longer and his can increase patient anxiety expressed by physical and emotional discomfort. It is important for health care providers to tell patients how long they are expected to wait and also treat them with courtesy and respect to reduce their anxieties. This can improve patients' perceptions of their wait and result in increased patient satisfaction and improved patient-provider relationship.From the respondent’s assessment of the health facility environment, 41.3% of respondents felt the environment was unclean and unpleasant. The findings confirms a study by [12] in Bangladesh, a developing country where 43% of study participants felt dissatisfied did so for reasons related to poor/ unclean environment, no toilet facilities and poor beddings at the clinics. In the same study it was noted that in Bangladesh the mean waiting time across all facilities was 39 to 40 minutes. Even though Bangladesh reported a lower waiting time period for a developing country, they also reported poor quality of care represented by poor and less consultation time. During focus group discussions, the participants intimated that the toilets and bath rooms were very dirty. This they said was largely due to lack of running water. Perceptions of poor care can emanate from a situation where a health facility has unclean rooms and bathrooms. Unclean rooms can become contaminated and contribute to hospital acquired infections in patients. This fact was long noted by Florence Nightingale when she stated that the sick room itself will interact with the disease and cause harm to the patient [13]. It is therefore critical that facilities maintain some acceptable levels of hygiene, provide some comfort, clean seating and bath rooms. It is conclusive that it is not only the wait that brings dissatisfaction but also the environment in which the patient waits.

4.2. Availability of Material Resources

- Societies that have achieved the lowest levels of maternal mortality have done so by preventing unwanted pregnancies, reducing the incidence of pregnancy complications and by having adequate and equipped facilities to treat pregnancy and labour related complications [14]. This assertion underscores the importance of material resources in the delivery of quality maternal health and the achievement of desired health outcomes. Materials, which include medicines, supplies and logistics systems, are critical to good performance of the health care system. Medicines are the most important indicator of quality commonly cited by health care consumers. On availability of material resources, 84.5% of the respondents indicated that all prescribed medications were received at the health facility. 90% of the respondents intimated they have had seats to sit on when they last visited the health facility. 53.6% of the respondents also asserted that there was enough space at both the labour and maternity wards when they last visited the health facility, whiles 64.9% of the respondents who last delivered in a health facility slept on a bed. This is collaborated by the focus groups where 90% of the participants observed that the health facilities had the necessary tools to work with. However, an earlier study [15] on resources for quality maternal health delivery noted inadequate material resources as a bane to achieving quality maternal health care delivery. The study noted that infrastructure and financial problems were critically limiting the delivery of services. This was also earlier observed by [16] He noted that a major problem hindering quality delivery of ANC is inadequate resources. In a qualitative study in Zimbabwe [17] health workers during in-depth interviews expressed concern over shortage of antenatal resources such as medications. This study on the other hand noted the availability of routine resources. 84.5% of the respondents said they had received all the prescribed medicines at the health facility. In a study conducted in Gambia [18], they noted that quality of services was affected by shortage of essential medications. The study noted that in many facilities the available supplies were inadequate and erratic. From the in-depth interviews with health personnel it was noted that supplies of medications and other materials are adequate though not regular and at times erratic. In this study, the supply of essential emergency medicines was limited. 54.8% of respondents affirmed this. This supports [15] that intermittent shortage of essential medicines in the hospitals is a chronic problem. The availability of blood is essential and life saving. 82.2% of respondents said blood was not readily available for transfusion purposes. The shortage of emergency medicines and blood is worrying. This stems from the fact that Anemia and Hemorrhage are leading causes of maternal mortality. There is a strong association between maternal mortality and blood transfusion and the provision of such critical supplies cannot be underplayed as it undermines effective maternal health care provision. Governments and donors agencies must establish and maintain budgets for blood and essential emergency medicines for all maternal and child health units.

4.3. Adequacy and Quality of Staff

- Human resource is the bedrock for the provision of quality maternal health services. It is therefore important to ensure the availability of quality and adequate human resource to deliver quality maternal health care. In this study, it was noted that 6.1% of respondents were attended to by a medical doctor. Majority, 62.4% were attended to by midwives, 31.5% of the respondents were attended to by a nurse. 47% of the respondents said the staff quality were enough, whiles 53% thought that staff numbers were inadequate to handle clients that come to the health facilities. The skilled delivery is 68.5% in the metropolis compared to a report of 84% in 2008 of urban deliveries nationally [7]. The same report notes that rural skilled deliveries are 43%. The 68.5% observed in this study of a metropolis clearly indicates that Tamale cannot be described as entirely urban. In the interviews with staffs, majority of them asserted that they were being over stretched and work beyond the normal working hours because of their limited numbers. A study in Palestine [19] noted the lamentations of a Nurse that they are given loads that are extremely exceeding their abilities as individuals and humans. It is “insane” she observes. A study reported that Ghana’s health professional staff reported working long hours. In Ghana, the doctor-patient and Nurse patient ratio it is reported to be 1:10,000 and 1:1240 respectively [20]. The in-depth interview with staff revealed that some doctors consult with more than 50 clients a day. It further revealed that three to four nurses attend to 75 to 85 clients at the ANC units at the Central and West Hospitals. FGDs also confirmed that there were not sufficient staffs. Participants expressed their frustration of the inadequate staff numbers that causes long waiting time at the facilities.“any time you go to the hospital, you spend so much time because there is no enough workers. You may see one or two nurses doing all the work. They cannot attend to us early so we just sit and wait…” On staff quality, majority of staff reported that they attend fewer refresher training than they should with some reporting that they have not had any refresher training over the last three years. The few of them who have had training reported having it once over the last four years. Nurses and Midwives are the key front line staff in most health care delivery systems and their contribution is crucial to meeting MDG five. There is however growing evidence of the impact of inadequate numbers of nurses and midwifes on the delivery of maternal health care. The causes of low staff numbers are multi faceted and include several push and pull factors. These are under supply of new staff, poor human resource planning and allocation, poor retention polices, poor incentive packages and lack of progression through career development plans.To make progress in MDG five there must be a search for solution which has to focus on providing conducive work environment, refresher training, opportunities to progress professionally and also incentives and motivation to returning Nurses and Midwives. These strategies fall in line with the WHO Global Standards for professional nursing and midwifery education and training and should be adopted to enhance adequacy in numbers and quality in maternal health care delivery.

4.4. Communication and Interpersonal Relationship

- It is reported widely that interpersonal relations between health care providers and clients is one of the key factors to improved client satisfaction, up-take and sustained use of services, compliance and better health outcomes [12, 19, 21]. Interpersonal relations has to do with effective communication with clients, reception of clients to the facility, how friendly service providers were to clients and the general attitude of health service providers to clients.From this study, 58.7% of respondents reported that the health professionals were not friendly. Earlier studies conducted, [15, 22, 23] have all indicated that health professionals are seen as unpleasant and unfriendly. A review report by Ministry of Health Ghana cited poor interpersonal relations, unfriendly and disrespectful staff attitude as a major cause of client dissatisfaction. A participant at a focus group narrated the following experience; “the nurses and midwives did not care about me and I was in pain for three days”. She also said when she started delivering, there was no person around and the baby was more than half way out before a nurse or midwife was prompted and she rushed to me with “kulikuli” (a local snack) in her hand. Reports of this nature are very common and yet, on their part, all the health personnel during the in-depth interview said they have cordial, friendly, good rapport and good relationship with their clients. They admitted however, that they at times have issues with some clients especially when they have to work with an overwhelming numbers of clients at the same time.The issue of poor staff attitude from the perspective of clients is nagging and can be improved through sustained training of staff in communication skills as well improvement in work environment and motivation of staff. The critical task is to create an open and transparent communication environment. Such an open environment can build an effective Nurse-Patient relationship that is therapeutic. It will optimize patients’ involvement and compliance in treatment by building patients sense of safety in the hands of caring professionals.

5. Conclusions

- To attain some levels of achievement in relation to MDG five it is imperative that the health system of Ghana deals with the issues which hinder the provision of quality health care services. The system has to bring in changes to improve the delivery of maternal health care services. The areas for health system strengthening should include improving on the time Clients have to wait to receive services. Improving on the facility environment, both internal and external is also crucial for client satisfaction and appreciation. A healthy working environment is equally necessary for staff motivation and output in performance. The availability of material resources in the delivery of maternal health care is critical. It was noted that very critical and important supplies such as emergency drugs and blood are not in regular supply. The erratic supply nature of these essentials can severely affect and hamper the objective of MDG five and reverse gains made in maternal care. As we approach accounting for the MDGs, there is urgent need to look at strengthening the building blocks of health systems and particularly reformulating new antenatal models that will enhance quality for maternal health care delivery. This strengthening should cut across urban and rural settings as both are in dire need.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML