-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2014; 4(6): 225-233

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20140406.02

Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness: A Study of Postpartum Women in a Rural District of Ghana

Robert B. Kuganab-Lem1, Razak Dogudugu2, Ladi Kanton1

1Department of Allied Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana

2Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Regional Hospital, Bolgatanga, Ghana

Correspondence to: Robert B. Kuganab-Lem, Department of Allied Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

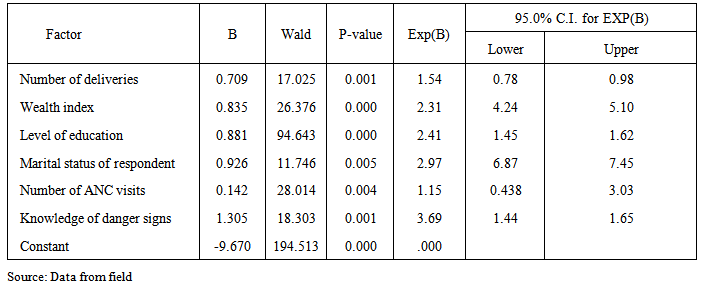

Adequate birth preparedness and complication readiness planning could determine the survival of a pregnant woman and her unborn child. The aim of this study was to determine the status of birth preparedness and complication readiness among postpartum women in the Sisala East District of Ghana. A cross sectional descriptive study was conducted in 40 communities of the district. The results from 400 respondents showed that 58.0% of the respondents sought prenatal care during the first trimester of pregnancy while 1.5% did not seek any prenatal care in the entire duration of their pregnancy. Home deliveries formed 63.25% of deliveries in the study sample which was mainly attributed to the lack of health facilities in the study communities. Age (p = 0.001), educational level (p=0.001) and socio-economic status of respondents were significantly associated with the use of skilled delivery services. Also, 79.0% of the respondents were aware of the possibility of severe bleeding during pregnancy while 72.8% mentioned eclampsia as one of the dangers or risks during labour. Only 23% of the respondents met or followed the steps of birth preparedness and complication readiness plan. Factors that were found to influence birth preparedness and complication readiness include; number of deliveries (p=0.001), wealth index (p=0.001), level of education (p=0.001), marital status (p=0.001), number of ANC visits (p=0.004) and knowledge of danger signs (p=0.001). Only 4.5% of the communities had emergency transport arrangements for pregnant women whereas none of them had emergency financial support services for pregnant women. It is important therefore to continuously maintain the strategies to get women plan adequately for child birth and thus equally ready in the event of pregnancy and birth complications.

Keywords: Postpartum, Birth preparedness, Complications readiness

Cite this paper: Robert B. Kuganab-Lem, Razak Dogudugu, Ladi Kanton, Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness: A Study of Postpartum Women in a Rural District of Ghana, Public Health Research, Vol. 4 No. 6, 2014, pp. 225-233. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20140406.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Inadequacy or lack of birth and emergency preparedness is one of several factors contributing to maternal deaths. Birth and emergency preparedness is an integral component of focused antenatal care which involves planning with the key stakeholders; the health provider, pregnant women and relatives and the community (Moran et al., 2006). Udofia (2013) noted that pregnancy and childbirth are normal physiological events and the desire of any family at the end is to have a healthy mother and a healthy baby and when this happens, pregnancy can be regarded as a joyful event and the birth of a child celebrated. Adequate birth preparedness and emergency/complication readiness (BP/CR) planning could determine the survival of a pregnant woman and her unborn child (Onayade et al., 2010). BP/CR planning is a key component of globally accepted safe motherhood programs. It helps women to reach professional delivery care when labour begins and reduces delays that occur when mothers in labour experience obstetric complications (Hailu, Gebremariam, Alemseged & Deribe, 2011).Birth preparedness programmes generally address ‘three delays’ to care-seeking for obstetric emergencies; delay in recognition of problem, delay in seeking care, and delay in receiving care at health facility. These delays represent barriers that often result in preventable maternal deaths (JHPIEGO, 2004). The safe motherhood programme defines a range of complementary interventions to improve maternal and new born health, one of which is the birth-preparedness package. The purpose of the package is to encourage pregnant women, their families, and communities to plan for normal pregnancies, deliveries and to prepare to deal effectively with emergencies if they occur (McPherson, Khadka, Moore and Sharma, 2006).BP/CR plan reduces delays in deciding to seek care in two ways. First, motivating pregnant women to plan to have a skilled provider at every birth. If women and families make the decision to seek care before the onset of labour, and they successfully follow through with this plan, the woman will reach care before developing any potential complications during childbirth, thus avoiding the first two delays completely. Second, complication readiness plan raises awareness of danger signs among women, families, and communities, thereby improving problem recognition and reducing the delay in deciding to seek care (Hailu et al., 2011).The BP/CR plan also encourages women, households, and communities to make arrangements such as identifying or establishing available transport, setting aside money to pay for service fees and transport, and identifying a blood donor in order to facilitate swift decision-making and reduce delays in reaching care once a problem arises. To have birth preparedness and complication readiness at the provider level, nurses, midwives, and doctors must have the knowledge and skills necessary to treat or stabilize and refer women with complications, and they must employ sound normal birth practices that reduce the likelihood of preventable complications. Birth and emergency planning is important because of the unpredictability of obstetric complications. It has been acknowledged that receiving care from a skilled provider is the single most important intervention in safe motherhood but often women are confronted with delays in seeking care (Udofia, 2013).Adabre (2012) stated that there is some lack of women empowerment in the Sissala East District as a result decision about health care choices are often left in the hands of male partners who consult a soothsayer and make pronouncement on the outcome of an expected delivery before a woman in labour is sent to a clinic to deliver. That may delay efforts in seeking professional care and mortality may occur.Despite the great potential of Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness in reducing the maternal and new born deaths, the successes of this strategy is not well known in most of sub-Saharan Africa.According to the 2012 Annual Report of the District Health Directorate of the Sissala East District, uptake of skilled delivery services was 44.2%. The report also stated that maternal mortality situation has worsened with maternal mortality rate of 97 per 100,000 live births in 2010 as against 190 per 100,000 births in 2012. This above 100% increase was attributed to pregnant women who reported late with obstetric complications in the health facilities. This study sought to assess the awareness of birth preparedness and complication readiness strategies among postpartum women in the Sissala East District of Ghana.The Sissala East District is located in the North- Eastern part of the Upper West region of Ghana with total land size of 4,744 sq. km, representing 26% of the total landmass of the region. It shares boundary at the North with Burkina Faso, at the East with Kassena Nankana and Builsa Districts, to the South East with West Mamprusi District, South West with Wa East and Nadowli Districts and to the West by Sissala West District. The district has sixty one communities with a total population of 56,528 and an annual growth rate of 1.9%. Adult literacy rate is low (59%) Male female ratio is 96 males to 100 females, women in fertility age (WIFA) is 23.7% and 7% of women 15 to 49 years are in marriage before age 15 (GDHS 2008). The settlement pattern is highly dispersed and rural by nature. More than 80% of the people are living in rural settlement and are engaged in farming.The district has a major problem of poor road infrastructure. This in effect affects the socio-economic development of most communities in the district. Typical examples of such communities include Gwosi, Santijan and Bawiesibelle which are almost cut off from the rest of the communities in the district during the peak rainy season (Sissala East District Profile 2010).

2. Methodology

- The study was a cross sectional descriptive study in which both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods was used. The study population was 2 months postpartum women. A 40 x 10 (40 communities with 10 respondents) multistage cluster sample procedure was used. The communities were selected using probability proportional to size (PPS) method. By this method the populations of all the communities in the district were summed cumulatively and the sampling interval calculated. Quantitative data were also collected by the use of structured questionnaires. These were based on socio-demographic characteristics, household characteristics, wealth index, BP/CR practice, maternal knowledge of obstetric complications and community support and emergency system for pregnant women. The qualitative arm of the study employed focus group discussions among the respondents. Information was gathered on the barriers to adequate preparation towards delivery, spousal support and attitude towards birth preparedness, complications readiness and knowledge of obstetric complications.

3. Data Analysis

- Quantitative data collected were entered into SPSS version 21.0. Univariate, bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed for the quantitative data. Mean differences were considered to be statistically significant at p<0.05. Independent variables found to be statistically significant at the 0.1 level based upon the results of the bivariate tests, were entered as potential variables included in the logistic regression models. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used because the main outcome variable was binary and it also allowed for testing for confounding and independent contribution of potential factors that influence birth preparedness. The focus group discussions were recorded with a voice recorder after which the recorded tapes were transcribed. A thematic analysis was then carried out for this qualitative data.

4. Results

- The results of the study are presented as follows;

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

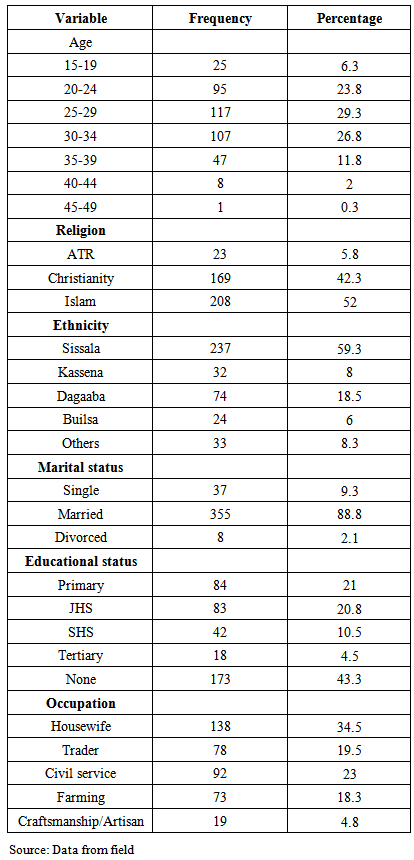

- The mean age of the respondents was 26.83 ± 6.47 (mean ± SD) with a range of 15-49 years. Majority of the respondents were within the age group of 25-29 and formed 29.3% of the study population. Muslims formed the majority of the study sample and represented 52.0% while African Traditional religion believers were the minority group and formed 5.8% of the study sample. The dominant ethnic or tribal group of the study was Sissala who formed 59.3% of the study sample. About 88.8% were married with 9.3% being single. There was also 1.8% who divorced. Also, 4.5% were educated to the tertiary level while 20.8% and 21.0% were educated to the JHS and primary levels respectively with 43.3% without formal education. Another 34.5% of the study sample was housewives and unemployed while18.3% was farmers. Civil servants formed 23.0% of the respondents.

|

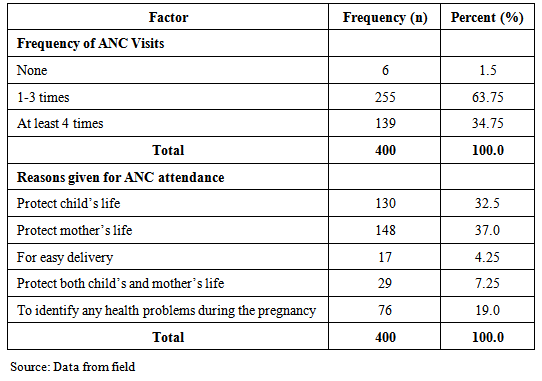

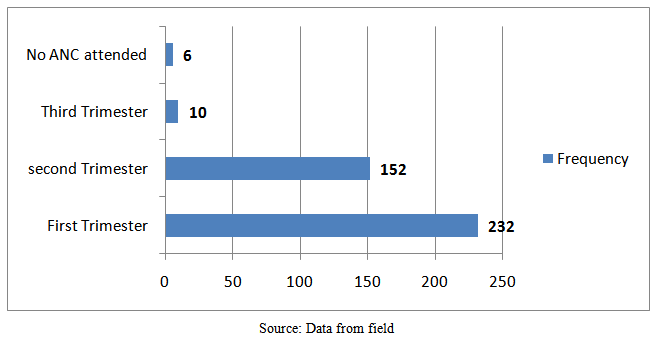

4.2. Utilization of Prenatal Care

- The study assessed the use of prenatal care services among the respondents. The results showed that 58.0% sought prenatal care during the first trimester of pregnancy while 38.0%, 2.5% and 1.5% sought prenatal care in the second trimester, third trimester and the entire duration of their pregnancy as shown in figure 4.1. For ANC visits, 63.75% made more than one visit while 34.75% made a minimum of four ANC visits in the entire duration of their pregnancy as shown in Table 4.2.

|

| Figure 4.1. Timing of ANC among respondents |

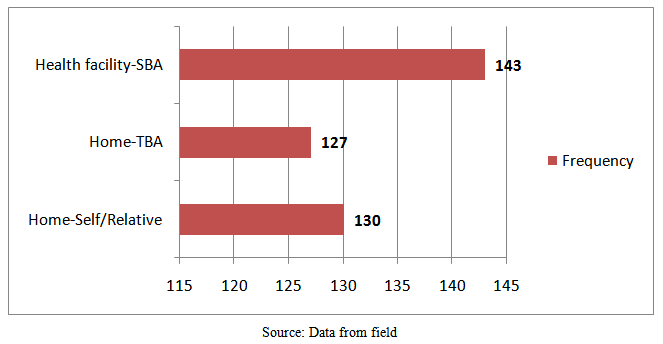

4.3. Utilization of Skilled Delivery Services

- Majority of the respondents who formed 63.25% of the study population delivered their latest child at home. Home deliveries were either conducted by Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) or by relatives who were mainly in-laws or mothers of the respondents. TBAs conducted 31.75% (127) of the home deliveries whilst 31.5% (126) of the home deliveries were conducted by relatives as shown in figure 4.2. Deliveries that were conducted in health facilities by Skilled Birth Attendants (SBAs) were 35.75% (143).

| Figure 4.2. Place of delivery |

4.4. Relationship between Place of Delivery and Socio-demographic Characteristics

- Bivariate analyses showed that older women delivered at home as compared to younger women who delivered in health facilities (p = 0.001). However, religion had no association with the use of skilled delivery services (p=0.09). Educational level of respondents was also found to be significantly associated with the use of skilled delivery. Services (p=0.001). Equally, the wealth index of respondents was found to have a positive relationship with the use of skilled delivery services. Women with low wealth index mostly delivered at home whilst those with high wealth index delivered in health facilities (p=0.001). Parity is also a significant factor in the use of skilled delivery services. As the number of deliveries by a woman increases the less likely she delivers at home. Women doing their first delivery or second deliveries are more likely to deliver in health facilities.

4.5. Knowledge of Danger Signs during Pregnancy

- The results show that 79.0% of respondents were aware of the possibility of severe bleeding occurring during pregnancy, while 60.3% suggested that abortion could occur during pregnancy. Another 56.5% and 64.5% suggested respectively that severe waist pains and anemia can be experienced by a pregnant woman. Other possible or potential dangers that were mentioned include vomiting, oedema and severe headache. Also, eclampsia, retained placenta, severe bleeding and malpresentation were stated as dangers during labour by 72.8%, 43.8% and 79.3% of the respondents respectively. A few people mentioned prolong labour as one of the risks or dangers during labour.

4.6. Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness

- The birth preparedness plan was considered based on arrangements that were made for a blood donor, transport, a delivery pack (items for the baby, mother and delivery) a caretaker and discussions that were made with the family before labour and child birth. Respectively, 3.0%, 97.0%, 46.0%, 39.2%, 53.3% of the respondents arranged for a blood donor before delivery, did not arrange for any blood donor, made some financial savings towards delivery, bought a delivery pack before labour or arranged for transport before delivery. 38.0% of the respondents arranged for a skilled birth attendant before labour while 31.7% of the respondents discussed their birth plan with the family members before delivery.

4.7. Composite index of Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness

- As shown in Table 4.3, a composite index of birth preparedness and complication readiness was created using seven variables which include financial savings, transport arrangement, blood donor arrangement, caretaker arrangement, and arrangement with a skilled birth attendant. The other variables that were added are discussion of birth plan with the family and purchase of a delivery pack. These variables were selected based on the birth preparedness matrix as recommended by the Safe Motherhood Project of the World Health Organization. A binary scale was drawn by scoring respondents who made any of these variables ready before labour as one, whilst the respondents who did not make any arrangement of the variables were considered to be inadequately prepared for birth whilst those with a mean score of less than 3.5 were regarded as not prepared for birth and complications.

|

4.8. Factors that Determine Birth Preparedness and Complications Readiness

- From the multiple logistic regression analyses (Table 4.3) the number of deliveries by respondent was a significant factor of birth preparedness and complication readiness. Women who were delivering for the first time were found to have a birth plan and were prepared for birth as compared to those who had multiple number of deliveries (p=0.001). Wealth index was also found to be significantly associated with birth preparedness and complications readiness. 2.8% of the respondents reported that their communities have identified blood donors to donate blood during emergencies in labour and child birth.

4.9. Findings from Focus Group Discussions

- Focus group discussions were organized in the communities with the postpartum women. Women who were part of the focus groups were not interviewed with structured questions. The themes and extracts from these interviews revealed the following; high awareness level of transport arrangement before labour, low knowledge of need to identify a blood donor against emergencies, high level of financial preparations during pregnancy and a high knowledge level of dangers or complications during labour. Barriers to birth preparedness and complication readiness were also discussed and respondents revealed the following; a lack of money or financial constraints, low level of autonomy from spouses as well as unwillingness to change.

5. Discussion

5.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

- The study was conducted among women in fertile age with majority of them within the age group of 25-34 years which is consistent with the findings of the 2008 Demographic and Health Survey conducted in Ghana. This is attributable to the fact that women may start having children from age 25 or started having children earlier than age 25. Muslims formed the majority of the study sample and represented 52.0% which is contrary to the report by the Ghana Statistical Service (2012). Sissalas were the dominant tribe in the study sample (59.3%). This is consistent with the report by the District Planning Unit of 2011 which noted that Sissalas form about 74% of the population of the district and are mostly moslems. About 88.8% of the respondents were married with only 9.3% being single. The proportion of married women in the study far outweighs the national proportion of married women which is 42.9%. This could be attributed to the rural nature of the study area and also the religious affiliation of the study population. Largely, Muslim women engage in early marriages and also Muslim communities are mostly polygamous. Majority of the respondents representing 43.3% of the study sample did not have any formal education which is consistent with the finding of the 2010 Population and Housing Census which found that 44.2% of people in the Upper West region do not have any formal education. This figure is higher than 33.1% which was reported by the population census as people living in rural areas who do not have formal education. Only 4.5% of the respondents were educated to the tertiary level which is consistent with the 3% found by the GDHS of 2008.On the economic activities of the respondents, most of the women, 34.7% were housewives and unemployed which are slightly lower than the 37.4% of females in Ghana who are reported to be unemployed. Most of the women who were employed were engaged in farming or agricultural activities. This is far lower than the 72.6% reported by the GSS (2012). The difference could be due to the fact that most of the respondents were housewives.

5.2. Utilization of Prenatal Care

- The WHO (2007) recommends that pregnant women make a minimum of four ANC visits through the entire duration of her pregnancy. This is aimed at identify dangers or health risks associated with the pregnancy. In this study, only 34.7% of the respondents made a minimum of four plus ANC visits. This figure is far lower than that of the MICS (2011) which found that 84.7% of pregnant women in Ghana attended the minimum number of four visits. The proportion of pregnant women who made a minimum of four ANC visits in the Upper West region for the year 2008 was 73.4% as reported by the GDHS. The findings of this study does not support the findings of the 2011 MICS and 2008 GDHS reports due to the rural nature of the study area. Only 1.5% of the respondents did not seek any antenatal care in the entire duration of their pregnancy which is lower than the 4% of pregnant women in Ghana who were found not to seek antenatal care in the 2008 GDHS. This could be attributed to the intense education through community durbars and the media.The reasons for the use of antenatal care services differ among women. In this study majority of the women sought antenatal care to protect their lives which were earlier found by (Saaka & Iddrisu, 2014) that most women seek antenatal care to protect their health. Some of them representing 19% also said that they sought antenatal care to protect both the health of the mother and the foetus which supports earlier findings that antenatal care when sought at the right time helps to protect the foetus and the mother’s health (White, Dynes, Rubardt, Sissoko & Stephenson, 2013).

5.3. Utilization of Skilled Delivery Services

- The use of skilled delivery services helps in reducing mortalities among mothers and the infants. Complications are also well managed when women deliver in health facilities. In the study, 64.2% of the women delivered their latest child at home whilst 35.8% delivered in health facilities. The findings of this study support the findings of the 2008 GDHS and 2011 MICS which noted that skilled deliveries in the Upper West Region for 2008 was 46% and 60% respectively. The 35.8% found by this study which is lower than the figures established by both surveys could be attributed to the rural nature of the Sissala East District which has very deplorable roads and inefficient transport system which prevents women in labour from accessing health facilities. The findings of this study are however consistent with that of the WHO (2005) which estimated that 34% of mothers globally deliver with no skilled attendant. The study findings when compared with the national average of 59% of delivery assisted by a health professional show that majority of women in the study area deliver without assistance from health professionals. These findings support the assertion by the GDHS 2008 that assistance from health professionals during delivery is high in urban areas than rural areas, 84% versus 43% respectively. The main reason for home delivery was the unavailability of health facilities in the study communities as stated by majority of the respondents. White et al. (2013) noted that women in rural areas deliver at home because of the distance they have to travel before accessing a health facility. Deogaonkar (2012) also found that rural women deliver with ease as compared to their counterparts in the urban areas. He noted that they delivered at home because they did not encounter any difficulty with the previous deliveries and therefore have the notion that they can deliver with ease. This observation was noted in this study. High cost of delivery pack also hinders pregnant women from seeking skilled delivery. This reaffirms the findings of McCarthy and Maine (1992), UNICEF (2010) and the GDHS (2008) that wealth index of households or socio-economic status of pregnant women is a major determinant of the place of delivery.

5.4. Relationship between Place of Delivery and Socio-demographic Characteristics

- Results of this study found that age of a pregnant woman is significantly linked with the use of skilled delivery services. As a woman increases in age the less likely she is to seek assistance from health professionals in delivery. This observation supports the findings of GDHS (2008) and Abioye et al. (2001) who found that the age of a woman has a significant relationship with the use of skilled delivery services. It is likely that older women tend to have experience in delivery and feel that they can deliver safely without the help of any health professional. In consonance with the findings of Baral et al. (2010) religion and tribe were not significant determinants of skilled delivery services utilization but rather educational status and wealth index of the woman. Mrisho et al. (2007) also noted that as a woman’s level of education increases she becomes more empowered and can take decisions that affect her health and the health of her children.Parity is also a significant factor in the use of skilled delivery services (El-Badawy et al., 2004). As the number of deliveries by a woman increases the more likely she delivers at home whilst those with their first delivery or second deliveries are more likely to deliver in health facilities. About 90% of the women in the study sample with more than three children delivered at home. This could be attributed to the fact that they have experience in delivery and are not scared by the dangers of home delivery.

5.5. Knowledge of Danger Signs during Pregnancy

- The knowledge of dangers of pregnancy was high among the respondents. Most of women (79%) intimated that there could be severe bleeding during pregnancy. This supports the findings of JHPIEGO (2004) where they reported excessive or severe bleeding during pregnancy as the most common problem identified by women. This they attributed to the fact that TBAs and relatives who assist pregnant women to deliver at home usually encounter such conditions. Only some few people in the study sample mentioned other conditions such as oedema, severe headache and waist pains as some risks of pregnancy. According to Starrs (2006) knowledge of other danger signs during pregnancy is low because they are not considered as bein very serious dangers that can kill a woman or her unborn baby.

5.6. Knowledge of Danger Signs during Labour

- Knowledge of danger signs during labour and child birth was also high among respondents. Majority of the respondents thus 72.8% (291) mentioned eclampsia as one of the dangers or risks during labour. This confirms the findings of Thaddeus and Maine (2004) who reported that eclampsia is a condition that kills most pregnant women who go into labour in rural areas as a result of lack of transport services to health facilities. As the number of children increases the knowledge of danger signs during labour also increases and this is consistent with the findings of Del Barco (2004) who revealed that knowledge of danger signs in labour is positively associated with parity and education.

5.7. Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness

- The findings of the focus group discussions are in tandem with the results of the quantitative arm of the study which found mothers’ autonomy, mothers’ socio-economic status and knowledge level of obstetric danger signs as significant factors that influence birth preparedness and complications readiness among women. These findings are consistent with that of Ekabua et al. (2011) who found that women make financial preparations or savings towards delivery more than considering making arrangements for blood donors. Women who arranged for a skilled birth attendant were in the minority because of the limited number of health facilities and skilled birth attendants in the district. This was earlier reported by Ekanem et al. (2005) who noted that the number of skilled birth attendants and health facilities in rural areas are limited and therefore prevent pregnant women form making personal arrangement for birth attendants.Women who live in rural areas have challenges in getting transport to access health care services. Fajemilehin (1991) reported that transport arrangements are not made by pregnant women before delivery. In this study about 53.3% of the women made transport arrangements before delivery. Those who made the arrangements were mostly women whose husbands or relatives had means of transport such as motorbikes or tricycles.

5.8. Composite index of Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness

- A composite index of birth preparedness and complication readiness revealed that less than one-third of the women were prepared for birth and but however ready to mitigate any complications that could possibly come up. Ekabua et al. (2011) in their study in Nigeria found that less than half of pregnant women who deliver are adequately prepared for birth and to handle complications of birth. The lack of preparedness was blamed on their lack of awareness of the birth preparedness plan or birth preparedness matrix. The findings of this current study support that of Ekabua et al. (2011) because most of the women were not aware of the particular need to look for a blood donor before labour and delivery.

5.9. Community Support Services for Pregnant Women

- Community leadership has an important role to play in removing barriers to health care access as well as improving access to a skilled care provider/attendant for women and their newborn babies. In this study, only 4.5% of the respondents had community transport services to support them during labour. The WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF/World Bank (1999) noted that communities should have some emergency support services for pregnant women to help reduce the maternal mortalities. The lack of these support services in the communities is attributable to the high poverty levels of rural communities in Ghana. The near absence of identifiable blood donors in the communities in case of emergency situations means a lot needs to be done to achieve complication readiness.

6. Conclusions

- This study demonstrates that socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women have a significant association with the use of skilled delivery services. An alarmingly low level of awareness of the steps in birth preparedness has culminated in low facility delivery. The study also revealed that women who made a minimum of four ANC visits was low and most of the women never made adequate preparations before delivery. The failure to make adequate preparations for delivery is largely due to poverty and low educational status of women. There is thus a need to develop strategies that will promote the adoption of BP/CR and increase the capacities of rural communities to design community-level systems to provide emergency funds, transport, and create pools of blood donors.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML