-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2014; 4(5): 195-202

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20140405.07

Exploring Women Knowledge of Newborn Danger Signs: A Case of Mothers with under Five Children

Robert Kuganab-Lem1, Adadow Yidana2

1University for Development Studies, Department of Allied Health Science, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Tamale, Ghana

2University for Development Studies, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Tamale, Ghana

Correspondence to: Adadow Yidana, University for Development Studies, Department of Community Health and Family Medicine, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Tamale, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The future of humanity in any part of the world is dependent upon the rate of infant’s survival at any given point in time. Many infants or neonates die out of avoidable diseases. Many infants across the globe are handled by their mothers; as such the knowledge of such mothers on the signs and symptoms of ill-health with regard to the infants is very important in curbing morbidity and mortality. Field data for this study was gathered from two sub-districts (an intervention and comparison communities) in the East Mamprusi District of the Northern Region of Ghana, using structured questionnaire. Results of the study, which sought to explore women knowledge of neonatal danger signs, revealed that many of the women have limited knowledge regarding neonatal danger signs. As far as the quality of antenatal care is concerned, it was observed that many of the women get the standard antenatal care as recommended by World Health Organisation. This study thus suggests that as part of health education and sensitization, women should be taken through danger signs prior to their discharge from hospital so that they can easily detect signs and rush to health care facilities as and when necessary.

Keywords: Neonatal, Danger signs, Mortality, Knowledge, Complication, Pregnancy

Cite this paper: Robert Kuganab-Lem, Adadow Yidana, Exploring Women Knowledge of Newborn Danger Signs: A Case of Mothers with under Five Children, Public Health Research, Vol. 4 No. 5, 2014, pp. 195-202. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20140405.07.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In societies across the globe, pregnancy and child birth are events that women are so much elated about and do not often wish to miss. In view of this, losing a child during or after birth is a painful experience women do not wish to experience. It has been observed that most of the under five (98%) mortality occur in developing countries [1]. Neonatal mortality, defined as death of an infant during the first 28 days of life, is a major challenge that confronts many developing nations [2]. Many women and their newborn babies are often at risk of developing complications during pregnancy or childbirth. As noted in most developing countries, research shows that most neonatal deaths occur at home [1, 2]. In a related research conducted at Uttar Pradesh, [3] observed that most of the home deliveries are mostly supervised by untrained personnel. As [1] has indicated in their research in India, many respondents indentified continuous crying of a baby as a manifestation of neonatal illness. As the case may be, when neonatal complications occur, care and care seeking among mothers is often impeded by a variety of cultural, logistical, and financial barriers, including what [4] describes as norms of poor hygiene and isolation. Indeed, reducing neonatal mortality rate by two-thirds by the year 2015 is one of the targets set by many developing nations [5]. Evidence from clinical and program research suggests that effective neonatal health interventions could be bundled together to suit existing health systems [6, 7]. What must be noted is that newborn morbidity and mortality continue to increase significantly in developing nations including Asia and Africa [8, 9]. In situations like this, knowing the danger signs of neonates is one way of seeking early care. However, [3] have observed in their study that only 37% of mothers had knowledge of loss stool as a neonatal danger sign. Aside the above mentioned issues, the suboptimal newborn care practices that still persist also contributes the increasing rate of neonatal mortality, contributing about 40% of all under-five deaths world-wide [10, 11]. Though global estimates of neonatal mortality rate have decreased from 33.2 to 23.9 per 1000 live births between 1990 and 2009, and a reduction of 28% or 1.7% per year [12], the situation in low income countries record the lowest reduction of 17% compared with 40% in developed countries. In the opinion of [5], the primary cause of neonatal death is sepsis (pneumonia, meningitis, neonatal tetanus, and diarrhoea). Though this may be so, others have argued that newborns health is closely related to the state of being of their mothers, though they have a unique need that ought to be addressed by health care practitioners [13]. In Ghana for instance, reducing or eliminating neonatal mortality requires sustainability of care, often lacking in many communities. It is worth noting that neonatal mortality rate in Ghana is 43 per 1000 live births [12]. In the opinion of [14], most neonatal deaths occur at home in low resource setting against a backdrop of poverty, unskilled home deliveries, ignorance, suboptimum care-seeking and weak health systems [3]. There are some who are of the view that current effort at reducing neonatal mortality is hindered by poor understanding of the social determinants of health as well as danger signs of neonate and putting into place appropriate strategies to reduce its impact [1]. This suggests that most of the neonatal deaths in high-mortality regions are due to preventable and behavioural modifiable causes. However, the extent to which preventive measures could reduce neonatal mortality is not known [14, 15]. Low utilization of available health services, such as supervised deliveries and post natal care continue to persist even where financial and geographic access is deemed adequate [16]. As people attribute high neonatal deaths to low utilization of neonatal care services at crucial stages of pregnancy, delivery, post-partum and post-natal periods [17, 18], neonatal complications during birth or after the birth of a child greatly contribute to neonatal and infant mortality in developing nations [19]. It is worth noting that complications can easily be averted if women are well educated on the nuances of neonatal health. This paper thus explored mother’s knowledge of danger signs of newborn babies.

2. Methodology

- The study was conducted in Ghana in the East Mamprusi District of Northern Region. The district is divided into five sub districts that include approximately 300 rural sparsely-located settlements. Average household size is 8 and almost half of married women (48%) are in polygamous unions. The educational status of women in the district is very low with 78% of them being illiterates. Interestingly, one in 6 pregnancies occurs in girls 15-19 years old [20]. A community-based non-randomized cluster survey was carried out between February and March 2013 involving two arms; one intervention study area and one comparison study area. The Intervention Group received an innovative intervention in addition to standard maternal health services available to women in Ghana. The Comparison Group received only standard maternal health services. A sample size of 1,020 (510 per study arm) respondents was estimated in order to have a 90% chance of detecting a significant difference (at 95% confidence interval) in the primary outcome measure (from a baseline figure of 43% in the comparison group to 58% in the intervention group), and assuming a correction factor of 2 (the “design effect”) for cluster sampling. Two sub districts were selected based on their geographical but which never the less have similar socio-economic, demographic and health care characteristics. A two-stage cluster sampling procedure was applied in each sub district to select the communities using probability proportional to size. In all, 30 clusters were selected from each of the study communities (intervention and comparison). In each cluster, 17 households representing 17 study participants were randomly selected and interviewed. A complete list of all households was compiled serially and systematic random sampling used in the selection process. In the first step, the total number of households in a cluster was divided by the expected sample size of 17 to give the sampling interval. The first household was randomly selected by picking any number from 1 to the calculated sampling interval. Subsequent selections were made by adding the sampling interval to the selected number in order to locate the next household to visit. If the selected household did not have a target respondent, the next household was selected using the systematic sampling procedure. The main research language was Mampruli since majority of the participants could not speak or understand English Language. For reliability and validity of data collected, all field assistants were given training on the objectives, methodology, standard measurement procedures, data recording, and administration of questionnaires. Face to face interviews were conducted using pre-designed structured questionnaires to collect representative data. Additionally, Focus Group Discussions were held with key community members. Data cleaning and consistency checks were done before the analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version18. Before the commencement of the research, research participants were educated on the essence of the study. Permission was also taken from Ghana Health Service.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Sample

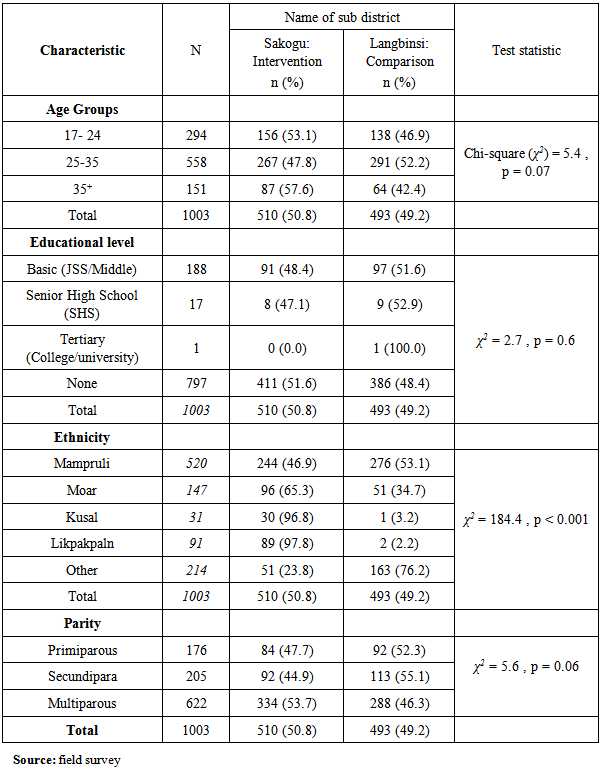

- In all, 1003 respondents were interviewed; 510 from Sakogu sub District (Intervention communities) and 493 from Langbinsi (Comparison communities). The mean age of the respondents was 28.5±6.6 years with the minimum and maximum ages of 17 and 49 years respectively and majority of them were in the age group of 25-35 years. There was a mean parity of 3.6± 2.1 with a range of 1-10. About 51.8% (520) of the respondents were from the Mamprusi ethnic group. Sadly, 79.4% (796) of them had no formal education. Table 1 below displays a comparison of the socio-demographic characteristics in the intervention and comparison communities.

|

3.2. Antenatal Utilization Decision Making

- As far as decision making with regard to ANC visits and choice of delivery sites, varying responses were provided by respondents. The most frequent person in decision to seek ANC care being mothers (51.3% and 48.7% in intervention and comparison communities). In the same vein, respondents mentioned husbands (50.7% and 49.3% in both the intervention and comparison) in decision making. These two persons play instrumental role in the determination of where to seek help. It has been observed that in the intervention and comparison communities, mothers, husbands and mother/father in-laws has equal power in terms of making decisions on ANC and choice of delivery sites. However, neighbours seem to have minimal role in making decisions regarding ANC visits as only fewer respondents mentioned neighbours as part of their decision making process.

3.3. Content and Quality of ANC Services

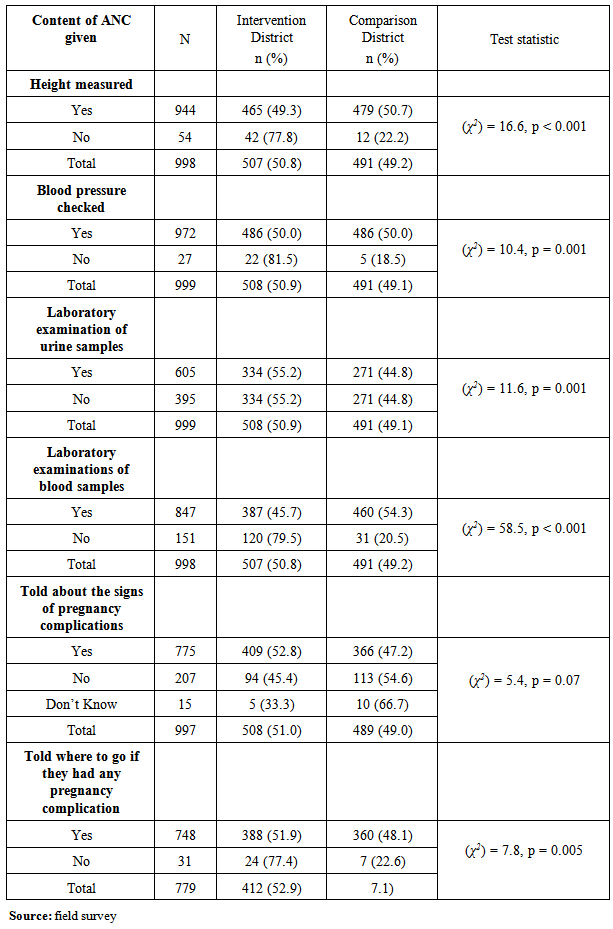

- With regard to the content and quality of ANC services, and as shown on Table 2, the following were responses; 94.6% (944/998) had their height taken. 77.7% (775/997) of mothers recalled they were educated on danger signs of pregnancy, 96.0% (748/779) were told of where to go if they had any pregnancy complication whilst 94.7% (950) were given drugs in order to prevent or treat malaria. However, only 51.5% (489) took the recommended doses of three in malaria prevention/treatment. Timing of the first dose of SP for a significant number of women was in 4-6 months of gestation.

|

3.4. Utilization of Institutional Delivery Services

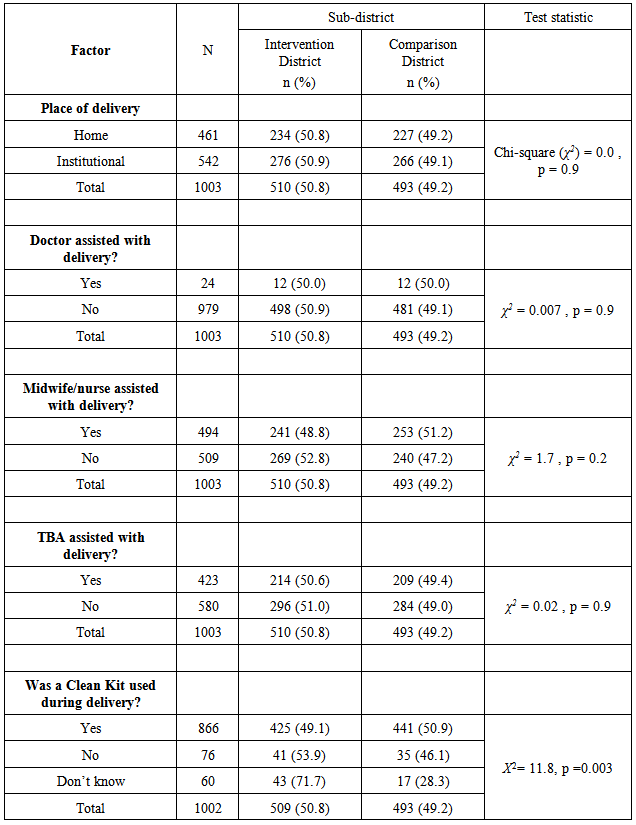

- Respondent were to provide information regarding the utilization of health care facilities as delivery sites. As table 3 shows, there was no significant difference in the uptake of skilled delivery services between the intervention and comparison communities. Traditional birth attendants (TBA’s) and Midwife/nurse were mentioned as people who assisted some of the respondents during delivery. The use of skilled birth attendants (such as doctor, midwife) during delivery was 54.0% in the study communities. Most respondents especially those from the comparison district (Langbinsi) reported that clean delivery kits were used during delivery.

|

3.5. Prevalence of Essential Newborn Care Practices

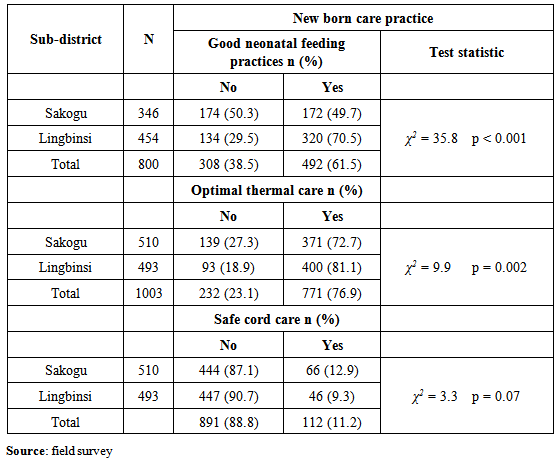

- Overall the prevalence of essential newborn practices with regards to safe cord care was exceptionally low. Langbinsi sub-district was better off in terms of good essential newborn care practices at baseline as is shown on table 4.

|

3.6. Management of Newborn Danger Signs

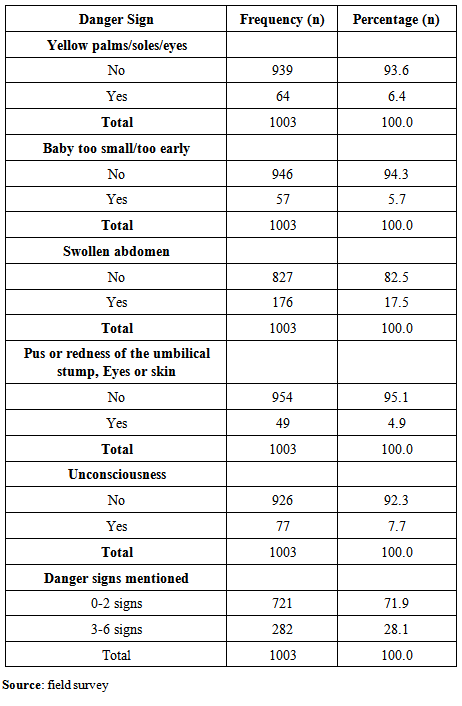

- Poor suckling or feeding and fever were the newborn danger signs that were frequently mentioned. Apparently, they were signs that will prompt women to take their newborns to health facilities for care. The knowledge levels on the rest of the danger signs among the respondents were very low (Table 5). Out of the ten known newborn danger signs, only 28.1% (282) of respondents could mention at least four danger signs.

|

4. Discussion

- In many developing countries, women and newborn babies are at risk of developing complications during or after childbirth [21]. Out of the 1003 respondents who were interviewed regarding their knowledge on neonatal complications in the studied communities, majority of them (58%) were from the Mamprusi ethnic group. Though there was almost a balance of the Mamprusi ethnic group in the comparison and intervention communities, the other ethnic groups were many in the intervention communities than the comparison communities. This means that many of the cultural practices would be skewed towards the major ethnic group. Out of the 1003 study participants, 797 of them, comprising 411 (51.6%) in the intervention communities and 386 (48.4%) in the comparison communities had no formal education. It was observed that the few who had secondary education were more likely to deliver at health care facilities. This study is consistent with other studies done in other parts of the world [22]. The results also found that majority of the study participants were in the age group 25-35 in both the intervention and comparison communities. This is not surprising because it appears to be the active reproductive and child bearing age among women [23]. This ties in well with [1] study that suggests that highly educated persons are more likely to make use of health care facilities than the non-educated persons.Another important dimension is the choice of a place of delivery, which has been consistently found to be associated with maternal and neonatal outcomes [24]. Delivering within medical facilities was attended to by trained medical staff. About 42% of those who delivered at home were attended to by traditional birth attendants whereas 49.3% of those who delivered at health facilities were attended to by midwives. This shows how important traditional birth attendants are in the health care delivery system. This finding is consistent with [22] study in Bangladesh which found that almost all births that took place at home was attended to by traditional birth attendants. What was also realized is that decision making in seeking antenatal care is usually made by the mother of the women or her husband. This revelation ties in with [19] study that suggest that mother-in-laws and husbands are key figures in deciding place of delivery. The content and quality of ANC is dependent upon the type of services provided at the health facility. On this note, women were asked whether specific services including taking of weight and height, measurement of blood pressure, and taking blood or urine samples were carried out for them. Of the total number, 94.1%, 97%, 60.3%, 84.4% indicated that their height, blood pressure, urine sample and blood sample were all examined respective during the ANC visits [26]. It is worth noting that almost all women who attended the recommended four antenatal visits had received quality ANC by virtue of the fact that they had received the recommended intervention [26]. As is expected in most cultural settings, most men are often not expected to accompany their wives to the antenatal clinic or be present during delivery [27, 28]. In determining good and essential newborn practices, both single and composite outcome variables were created: (a) Good cord care (defined as use of a clean cutting instrument to cut the umbilical cord plus clean thread to tie the cord plus no substance applied to the cord); (b) Optimal thermal care (defined as baby wrapped within 10 minutes of birth plus baby being dried/wiped immediately after birth); and (c) Good neonatal feeding practices (defined as initiating breastfeeding within the first one hour after birth, plus no prelacteal given and colostrums fed to the child). These composite variables were then dichotomized to Yes (all practices present) or No (one or more practices missing). Generally, good newborn care practices such as baby dried (wiped) immediately after birth before the placenta was delivered, use of a clean cutting instrument to cut the umbilical cord, non-application of substances on the cord, wrapping of newborn after delivery appear to be universally practiced in the study communities. However, combination of these individual practices was below recommended levels. Of the 1003 respondents, only 11.2% (112) were judged to have had safe cord care, 76.9% (771) optimal thermal care, and 61.5% (492/800) were considered to have had adequate neonatal feeding. All the respondents reported haven to apply some kind of substance including Shea-butter (locally produced oil), antiseptic, charcoal powder, chalk, ash on the cord stump. To ensure maximum thermal protection for the newborn, it is recommended that the newborn should be dried and wrapped immediately after birth but before the placenta is delivered, and bathed only after 24 hours from birth. This finding is contrary to similar studies such as [29] that suggest that umbilical cord care was very high. Mother’s knowledge of the danger signs of newborn complications is an essential step in the recognition of complications and a way towards reducing neonatal mortality [30]. From the study, it has been observed that the study participants had little knowledge regarding neonatal danger signs. In all, 93.6%, 94.3%, 82.5%, 95.1% and 92.3% did not know that Yellow palms, baby too small, swollen abdomen, redness of umbilical stump, and unconsciousness were neonatal danger signs respectively. Additionally, only 28.1% could mention up to 3 danger signs. These is not consistent with studies conducted in other parts of African were knowledge of danger signs was relatively higher [29; 30]. The poor knowledge may be due to the high illiteracy rate among women, and probably explains why neonatal mortality is still high. To ensure safe and complication free newborn, women are entreated to undertake early antenatal care within the first trimester. This is crucial because it allows for early detection and management of complications, as well as detection of existing diseases and treatment, promotion of health and prevention of disease [29]. The growing body of evidence from clinical and program research suggests that effective neonatal health interventions could be bundled together to enhance cost-effectiveness and to suit existing health systems [10, 6].

5. Conclusions

- As governments and stakeholders in developing nations strive to reduce maternal mortality by 75% by 2015, health workers (midwives) ought to provide comprehensive client friendly education and care to all women, especially expectant mothers. With a poor knowledge of newborn danger signs, tackling the problem this way will guarantee provision of essential neonatal care at birth as well as improve women knowledge of danger signs and symptoms of complications. Poor knowledge of neonatal danger signs was a significant issue identified that needs urgent action from policies makers within the health sector. Many of the participants, 76.7% were observed to be illiterates; suggesting why their knowledge of danger signs was very low. Quite a number of them did not know about birth preparedness, thus, a large proportion of clients were not prepared for obstetric emergencies. As [31] have pointed out, antenatal care in many developing countries reports ineffective organization of educational sessions and poor counseling for both birth preparedness and risk factors. Going by the findings, there is the need for quality of the information to be disseminated to women with regard to their newborn’s health and what danger signs to look for. It must also be added that issues that will prompt newborns returning to the health care facilities should be passed over to the mothers before they are discharged from hospital. As has been indicated, this is an important component that should not be missed [32, 33]. It is also necessary to put in place a well structured educational plan to work towards reducing the effects of the three delays that often lead to needless deaths of neonates would be reduced. Other measure includes modification of cultural norms to be consistent with best practices, a strategy that would make the education acceptable. Based on this, it is crucial for antenatal as well as postnatal care to place emphasis on birth preparedness, complication readiness as well as knowledge of neonatal danger signs to improve neonate’s quality of health.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML