-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2014; 4(5): 185-194

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20140405.06

Towards a Sustainable Health Care Financing in Ghana: Is the National Health Insurance the Solution?

Ebenezer Owusu-Sekyere1, Daniel A. Bagah2

1Department of Development Studies, University for Development Studies, Wa, Ghana

2Department of Social, Political and Historical Studies, University for Development Studies, Wa, Ghana

Correspondence to: Ebenezer Owusu-Sekyere, Department of Development Studies, University for Development Studies, Wa, Ghana.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

As part of rejuvenated efforts at pursuing sustainable health care financing options that promote universal coverage, Ghana has adopted a National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) to provide financial access and universal coverage for health care, which is key in promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health interventions for all at an affordable cost. However, since its operationalization in 2004, the policy is facing a lot implementation challenges that are threatening its viability. Our research investigates the financial sustainability of the scheme. This qualitative study was conducted between July, 2013 and July, 2014. Ten in-depth interviews were conducted with officials connected with the NHIS selected across the Ashanti and the three Northern regions of Ghana. Additionally, ten focus group discussions were also conducted and this was complemented by analysis of policy documents. The study reveals that the sustainability of the scheme is threatened by lack of funds which has resulted in indebtedness to service providers. Out-of-pocket payment has been re-introduced by service providers and in some cases, NHIS card holders who are unable to make upfront payment are rejected at health facilities. The study posits that the trend is likely to continue and perhaps even escalate unless a well planned policy intervention to refit the scheme is adopted and competently implemented.

Keywords: National Health Insurance, Cash and Carry, Equitable, Healthcare

Cite this paper: Ebenezer Owusu-Sekyere, Daniel A. Bagah, Towards a Sustainable Health Care Financing in Ghana: Is the National Health Insurance the Solution?, Public Health Research, Vol. 4 No. 5, 2014, pp. 185-194. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20140405.06.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- “I still look at the picture of my child and feel a sense of deep sadness. If we could have afforded the hospital or the medicines, would my daughter still be alive”? [1].This quotation from OXFAM represents the sentiments of Samata Rabi, a 50 year old mother who lost her youngest daughter because she could not afford to pay the insurance premium of GHc 15 (USD 10) as at 2011 which would have entitled her to free health care in Ghana. The story of Samata illuminates the susceptibility of the poor and marginalized in assessing health care. It is for this reason that providing citizens with accessible, affordable and quality healthcare continues to be the most important social objectives of all governments in Ghana. This is because there is demonstrated relationship between health and development as healthier nations also happens to be wealthier nations. Indeed, healthier populations are equipped to deliver much higher labour productivity, which in turn contributes to the creation of wealth for the nation. Thus, health is not only a human rights issue, but also a key driver of wealth creation, and ultimately of national development. Health care financing refers to the methods used to mobilize resources that support basic public health programs, provide access to basic health services, and configure health service delivery systems. It also includes resource mobilization, allocation, and distribution at all levels, including how providers are paid as well as motivation for users. Again, healthcare financing also includes revenue collection, pooling of risks, purchasing of interventions and putting in place technical, organizational and institutional arrangements so that health systems will perform its functions in protecting people financially in the fairest way possible. At the core of efficient healthcare financing schemes are the issues of equity, efficiency, sustainability, and quality [2]. Realizing that over 90% of the population in low-income countries is unable to seek appropriate health care because they could not afford the out-of-pocket payment at the point of service delivery, the 192 members of WHO in May 2005, endorsed a resolution entitled 'Sustainable health financing, universal coverage and social health insurance' which among other things, urged member states to develop their financing systems to ensure that their populations have access to needed services without the risk of financial disaster [2]. In recognition of this, most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Ghana not exclusive, have developed and implemented several development frameworks which recognizes the need to reform the health sector aimed at improving their citizens’ health status [3]. They include the Millennium Declaration, the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy and the Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS I and II), the 2007 Maternal Health Survey Report and the various health sector policies and strategies. These policies emphasize the critical role healthy lifestyles, health-enhancing environments and a functioning health industry play in improving health and socioeconomic development [4]. The policies are aimed at the provision of comprehensive health care system that promotes preventive and curative as well as rehabilitative services. The policies also acknowledge the need to promote a vibrant local health industry that would support and sustain efficient service delivery, create jobs and contribute directly to wealth creation and the attainment of national development goals [Ibid]. Ghana eventually adopted a National Health Insurance Policy in 2003 to provide health care financing options that ensure that the larger society is benefited in a way that limits up-front payments and instills confidence in the health system. Whiles there are success stories to tell since its introduction, persistently increasing claims and other implementation challenges have threatened the sustainability of the scheme. While this may be attributed to the increasing numbers of active members, moral hazards from both provider and subscriber ends may not be ruled out. This research tells some of the success stories and illuminates some major challenges of the National Health Insurance Scheme since its implementation. Of specific concern to this research is the issue of financial sustainability. Our hope is that the lessons that will be learned from this study will be useful not only for future policy formulation and implementation, but more importantly, can identify appropriate, cost effective and sustainable strategies for efficient management of the scheme. The study is organized in five main parts. The next section outlines the conceptual framework adopted for the study, which draws on the sustainability framework for health care financing. Section two is devoted to the historical antecedents of health care financing in Ghana. The search for sustainable healthcare financing received critical consideration in the third sections while the fourth section highlights some of the achievements of the NHIS and the last section discusses threats to the financial sustainability of the National Health Insurance Scheme.

1.1. Framework on Sustainable Health Care Financing

- The crucial and critical issue of development policy in developing countries is sustainability, its definition and measurement. Sustainability refers to the continuing ability of a project to meet the needs of its community [5]. The concept is seen as “development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [6]. Though the concept is generally credited to the 1987 report of World Commission on Environment and Development, that is the Brundtland Commission [6]. [5] argues that the concept has its origins as far back as 1798, when Malthus, an economist, argued that life sustaining systems would not be able to sustain life with time if population growth and attendant consumption was allowed unchecked. The concept, however gained much importance in the latter parts of the 20th century, when the United Nations explored the connection between environmental quality and quality of life. Sustainable development is a three-dimensional model of growth, which addresses the need to maintain the environment, economy and society [5]. Contributing to the debate, [7] describes the model of sustainable development as three props where the props refer to the economy, the environment and society. Similarly, [8] argues that a “sustainable system or development is one which suits environmental sustainability, economic sustainability and social sustainability.Sustainable healthcare financing involves a policy which utilizes the ability of all stakeholders to make health care viable and operational for a long period of time without collapsing, thus, ensuring perpetual existence. This is where universal health insurance offers the way. A well crafted universal health insurance makes health care acceptable, accessible, equitable, and affordable and delivers sustainable quality care. Health insurance schemes cannot be implemented in isolation. The success of their implementation depends on factors like affordability, unit of enrollment, distance, timing, quality and sustainability [9]. In their efforts to improve health systems, developing countries face the challenge of integrating traditional government health resources with a large and growing private health sector. Within such a ‘mixed health system’, where some poor people seek care from private practitioners, three financing and delivery mechanisms are key instruments that can improve access, availability, and quality of health services [10]. Kutzin in 2001 introduced a framework with the aim of developing a tool for descriptive analysis of the existing situation in a country’s health system with respect to healthcare financing and resource allocation, and equally as a tool to assist the identification and preliminary assessment of policy options. Kutzin’s presentation focuses on categorization and description of the elements of the financing system (collection of funds, pooling of funds, purchasing of services and provision of services) rather than on the relationship between financing and the broader health system. He emphasizes that the conceptual framework is driven by the normative objective of enhancing the ‘insurance function’ of providing access to care without financial impoverishment.Health financing is explicitly related to the overall role of health system functioning by distinguishing three components, which he referred to as three pillars: these he explains as Objectives, which includes broad health system goals and financing policy objectives; Functions and policies of health financing; and Contextual factors, particularly fiscal constraints Kutzin [11]. Among broader health system goals, Kutzin saw an important role for health financing in promoting universal protection against financial risk and promoting a more equitable distribution of the funding burden. Programs that have been implemented within this framework cover a broad spectrum of interventions that address specific challenges common to many developing countries, including reducing the fragmentation of private providers (franchises and provider networks), changing provider incentives and improving monitoring (accreditation and licensing models and insurance or voucher programs), and providing subsidies for targeted populations and high-impact interventions (public and private risk-pooling programs) [12]. While unable to transform health systems as standalone interventions, many of these programs can complement key elements of countries’ health care financing and delivery platforms.

2. Research Approach

- This qualitative study was conducted between July, 2013 and July, 2014. As a starting point, Ten in-depth interviews were conducted with officials from the NHIS selected across the Ashanti and the three Northern regions of Ghana. The Ashanti region was specifically selected for two main reasons; first, it is the most populous region in Ghana with a population of more than five million [13]. Second, it is the region that has been chosen for a pilot program under the National Health Insurance Scheme (Health Insurance Capitation Program). This piloted project has received stiff resistance from residence from the region and this has threatened the sustainability of the scheme. Available statistics from the scheme offices indicate that the introduction of the capitation program has seriously affected enrollment and renewal rate in the region. The choice of the three Northern regions is justified by the fact that they are the most deprived and marginalized social groupings in Ghana [14] and at the same time are the group that have subscribed and benefited most from the scheme [15]. The major issues that formed the fulcrum of the discussions were policy implementation, service delivery, sustainability and constraints of the policy.The second strand of the methodological approach involved Ten focus group discussions, four focus group discussions were conducted in the Ashanti region and the rest of the six focus group discussions were held in the three Northern regions. In the recruitment of members in the focus group, bias attempt was made to include more women than men. This is because the scheme has a special intervention for pregnant women to attend health facilities for free during pregnancy. Again, in the traditional setting of Ghana, one of the key responsibilities of women is attending to the sick and accompanying them to health facilities, especially children, the weak and fragile. They were therefore in a better position to give accurate responses on their perception, satisfaction or otherwise of the scheme and were able to explain better, the workings of the scheme based on their practical on-the-ground experiences with the service providers and scheme officials.Lastly, the study reviewed extensive literature on the subject and also benefited from official documentations from the National Health Insurance Authority, which is the official regulatory body of the scheme, managers of health facilities and other allied agencies connected to and working with the National Health Insurance Authority. These documentary analyses helped considerably in illuminating the true state of the scheme and also helped in checking and cross-checking some of the information obtained from the empirical data from the interviews and the focus group discussions.

3. Health Care Financing in Ghana

- Historically, Ghana’s policies on health financing have been fashioned out to suit the political ideology of the implementing government. Whiles the colonial master was capitalist oriented, immediate post independence ruling class were more socialist inclined and therefore place the government at the center of all policies. This section examines the influence of the different political ideologies on health care financing in Ghana.

3.1. Era of Free Medical Care

- Scholarships have chronicled that during the pre-independence era of Ghana, financial access to modern health care was predominantly by out-of pocket payments at point of service use [16]. After independence, the government of Ghana established a National Health Service (NHS) which was fully financed from state revenue. The NHS system which was seen as being progressive, provided service for everybody without any costs and insulated the poor and marginalized people from financial distress. The NHS system did not involve out-of-pocket payments at point of service and all such services were made free. This system, though lauded at the time, its sustainability was threatened and was short-lived due to the declined fortunes of Ghana’s economy culminating in inadequate resources and budgetary constraints. The quality of medical services deteriorated, medical services became attractive to the urban population, while the largely rural poor were excluded.

3.2. Out-of-Pocket Payment

- By the early 1970s, Ghana’s economy started stagnating, general tax revenue dwindled and therefore, the policy of tax-based health financing system could not be supported. A minimal user fees was thus introduced in 1971 to cover hospital procedures and overheads with the enactment of the Hospital Fees Decree 1969 which was later amended into the Hospital Fees Act 1971. The economic downturn in Ghana led to general decline in agricultural productivity as well as exports. There was also increased inflationary pressures, and a gradual build up of unemployment. With the Ghanaian economy literally on the verge of bankruptcy, Ghana had no choice but to accede to the then attractive proposals from the IMF and the World Bank. This led to the introduction of a structural adjustment program in 1983 [17]. Central to this was the goal of getting prices right by withdrawing subsidies and liberalizing the domestic and external trade regimes. Efforts were made in this regard to also encourage deregulation of various aspects of the economy, reduce the size of the state bureaucracy through civil service retrenchments, encourage the private sector, and promote the embrace of the market. There were budget cuts in social spending with health and to some extent education bearing the heaviest brunt. The government was forced to introduce full cost recovery (also known as cash and carry) into the health system with the introduction of the Hospital Fees Regulation 1985 (L.I.1313) which broadened the fees charged to include consultation, laboratory and other diagnostic procedures, medical, surgical and dental services, medical examinations and hospital accommodation [18]. The World Bank/IMF propelled a policy of privatization in the health sector as part of a whole module of macroeconomic structural adjustment program hoisted onto the Ghanaian populace. The main argument put forward by proponents of the health sector privatization was that it would increase the public’s appreciation of health services and prevent overuse [18]. In responding to the arguments of the poor potentially losing out on access to health care, the World Bank argued that, revenues from user fees could be used to subsidize those who could not afford care. Exemption schemes were also proposed to get round the threat of poor people being unable to afford adequate health care. However, a lot of these did not work out. Later empirical studies on the effects of the health sector reform component of the structural adjustment programs revealed severely awful consequences (Asenso-Okyere et al. 1997). Access of the poor to health services was adversely affected [17]. The Cash and Carry system of paying for health care at the point of service put an enormous financial pressure on the poor and served as a major barrier to health care access. Health care inequalities became widespread, especially around the later part of the 1990s and early 2000.

4. The Roadmap to Health Insurance in Ghana

- Ghana, recognizing the importance of health care to the quality of human capital, made several attempts at finding alternatives that will abolish the cash and carry system. The alternatives experimented proved unsuccessful, largely because of lack of resources and capacity of the government to pay for the budget of the health sector. Finally, the government took the decision to experiment with a social health financing initiative with the introduction of a health insurance scheme on a pilot basis in the 1990s. The thinking in major discussions on health service utilization and the burden of increasing cost of medical care was settling on community-based health insurance (CBHI) as a transitional mechanism to achieving universal coverage for health care in low-income countries. This was based on the theory that contends that health insurance lowers the cost of medical care at the point of use, thus effectively removing the financial barrier to access and utilization of health service will increase [19]. The empirical results have largely been positive and slightly controversial. To achieve the objectives outlined in the pilot program, a few districts were selected to experiment with the scheme because of the cost involved and the experiences of other countries that failed in the same endeavour because of inadequate resources.

4.1. Community Health Insurance in Ghana

- The first community health insurance (CHI) scheme in Ghana started at Nkoranza by the St Theresa’s Catholic Mission Hospital in 1992. It proved popular and endured the test of time [20]. The government therefore created a unit in the 1990s in the Ministry of Health (MOH) to establish national health insurance as an alternative to ‘cash and carry’. The unit focused its efforts and resources on consultancies and feasibility studies for a pilot social health insurance (SHI) scheme for the formal sector and organized groups such as cocoa farmers in the Eastern region. By 1999, the proposed SHI pilot had died a stillbirth without insuring anybody. No public acknowledgement or explanation was given for its demise. However, it appeared to be partly related to lack of leadership, consensus and direction in the MOH as to the way forward; as well as a failure to sufficiently appreciate the difficulties of implementing centralized social health insurance in a low-income developing country [20, 16]. Following the demise of the Eastern region pilot, the social security and national health insurance trust (SSNIT) started planning for another centralized health insurance scheme to be run by a company called the Ghana Health Care Company. Like the Eastern region pilot, it never took off despite the huge public expenditure on personnel, feasibility and software.In 1993, UNICEF funded exploratory research on the feasibility of district-wide community health insurance (CHI) for the non-formal sector in Dangme West [21], a purely rural district with a subsistence economy and widespread poverty. The study had strong support from the MOH. The study showed enthusiasm among community members for the concept of CHI. A pilot district-wide CHI was planned in the same district. At the local level, the district health directorate and research center, the district assembly (local government) and communities continued their collaboration and completed the design of the pilot district CHI scheme. The district assembly contributed part of its UNDP poverty reduction fund to support community mobilization and household register development, and WHO, AFRO and DANIDA provided start-up funding. Registration of beneficiaries and delivery of benefits started in October 2000. Provision of funds for the continuous implementation and evaluation was provided by the Ghana Health Service (GHS) and the MOH [22].Several other CHI schemes also called Mutual Health Organizations (MHO), also sprang up in Ghana. Their rate of development accelerated exponentially after 2001 [23]. Many were sponsored by faith-based organizations. Development partners that played a major role in their support were DANIDA (Danish International Development Assistance) and PHR-plus (Partnership for Health Reforms plus), an organization funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). These two organizations also jointly supported the development of a training manual for administrators and governing bodies of MHO [20]. Many of the MHO were in the Brong Ahafo and Eastern regions, related in part to the fact that in these regions MHO had active ‘champions’ in the form of technically well-informed regional coordinators in the GHS. Besides these CHI, the Christian Health Association of Ghana (CHAG), represented mainly by the Catholic Church, who had many mission facilities in these regions and actively supported the growth of MHO around its facilities.

4.2. Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme

- The development of the current National Health Insurance Scheme began with Ghana’s decision to access the highly indebted poor country (HIPC) initiative in March 2001. Among the areas where the government of Ghana was to expend the funds that would accrue from the HIPC initiative included funding of projects for poverty reduction and economic growth [24]. Inclusive of the areas that were to benefit from the initiative was the expansion of the social protection basket of the nation with much emphasis on the protection of the poor and marginalized, with special reference to women and children. To this end, the MOH in February 2003, allocated some of the HIPC funds to support the creation of government sponsored MHOs in all districts where they did not exist. By July 2003, the final version of the national health insurance bill (Act 650) was placed before the legislature for considerations and approval to be passed into law. The bill required the formal and the informal sector to enroll together in government-sponsored district MHOs. The national health insurance scheme is financed from a pool of sources which include individual premium payments ranging from GHȻ7.2 to 48.0 (roughly USD 3.6 to 24) per person per year. These premiums are progressive which means the rich pays more than the poor. This source contributes about 4% of the NHIS revenue. The major source of funding is the value-added tax of 2.5% on all goods and services earmarked for national health insurance constituting about 61% of NHIS revenues. Other sources include investment income or interest earned on National Health Insurance Fund reserves (17% of NHIS revenues), a 2.5% of social security contributions from formal sector workers (15% of NHIS revenues); and donor aid in the form of sector budget support2 (2% of NHIS revenues) [25]. Almost all outpatient and inpatient services targeting over 90% of the disease burden including essential medicines (as included in the NHIS approved list) are offered to the insured without any co-payments. The insurance is cashless and the insured are not required to make any payment at the time of health care delivery. Payments for referrals (under the gatekeeper system) up to teaching hospital are covered. However, HIV retroviral drugs, hormone and organ replacement therapy, heart and brain surgery other than the ones caused accidents, diagnosis and treatment abroad, dialysis for chronic renal failure and cancers are excluded from the insurance package.

5. The Picture so far

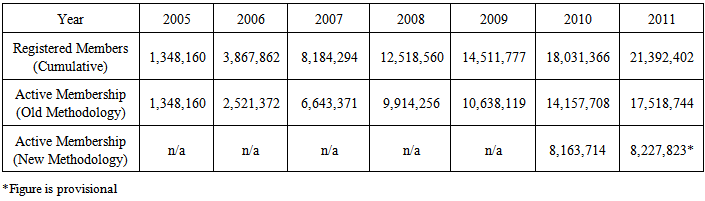

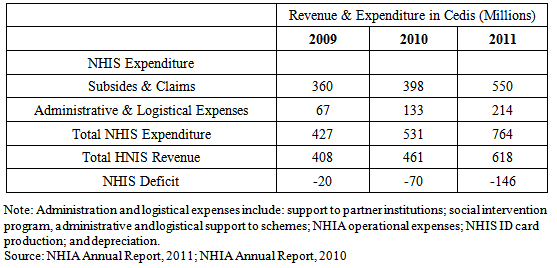

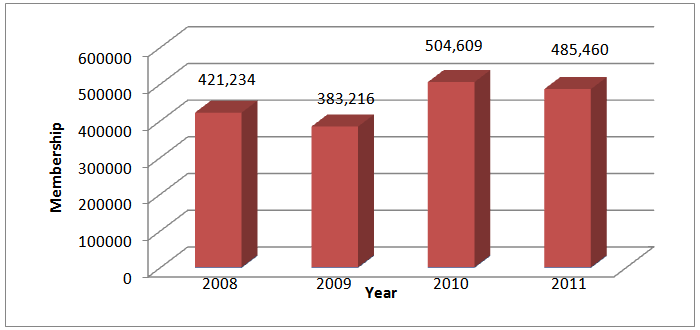

- The National Health Insurance Scheme, which was implemented in 2004, has been accepted by Ghanaians as one of the best homegrown social intervention programs to be introduced in the country. Our research reveals that the National Health Insurance Scheme has expanded access to health care for the majority of the population who hitherto could not afford health care under the ‘cash and carry’ system. As at the end of December 2011, the total active membership of the scheme increased from 8.16 million in 2010 to 8.23 million in 2011 showing an increase of 0.8% over the 2010 figure and representing 33% of the population (Table 1).

|

| Figure 1. Outpatient utilization trend from 2005 to 2011 [NHIA, 2013] |

| Figure 2. Free Maternal Registrations [NHIA, 2013] |

6. Threats to Financial Sustainability

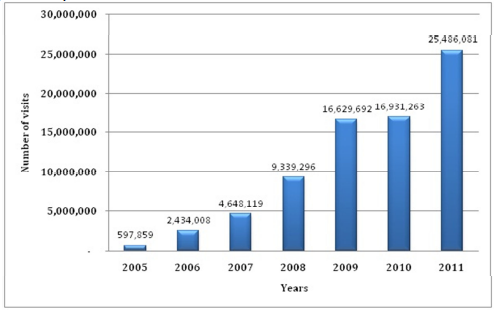

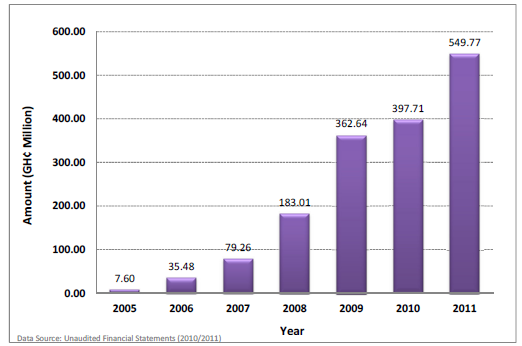

- There are emerging issues that seek to threaten the financial sustainability of the national health insurance scheme. They include corruption, delay in release of identity cards and many others. Whiles many of these are not new, their intensity and impact poses a fundamental challenge to the scheme. Prominent among the challenges is lack of funds that has led to the persistent indebtedness to service providers by the NHIA. The lack of funds has been blamed on escalating claims payment by the NHIA, see figure 3. The findings of this research show that claims payment is the major cost driver of the scheme. Claims payments increased from GH¢7.60 million in 2005 to GH¢549.77 million in 2011representing 76.2% of the total expenditure of the NHIA (figure 3).

| Figure 3. Claims Payment trend from 2005 to 2011 [NHIA, 2013] |

|

7. The Way Forward

- The importance of this research is its illumination of the fact that whiles universal access to health care through insurance is important, building pillars for credible and a sustainable funding source is even more urgent. Whiles many countries in sub-Sahara Africa rush to introduce social protection schemes for political reasons, building a sustainable component of funding is often overlooked. What is crucial is that many of these countries, Ghana not exclusive have large informal sector whose average incomes do not compel them to make contributions towards such schemes. Again, where compulsory taxes are introduced, like the case in Ghana, improper tax accounting procedures, political interference and corruption have many times led to the diversion of funds to other sectors that may be less pressing. In Ghana, the 2.5% VAT levy on goods and services is a statutory fund whose payment is charged to the consolidated fund. What it means is that the fund so accrued should be channeled to the NHIA within the legally mandated period; this is where the political machinations are rifed. The fact that the scheme is limping on one leg is no secret; for instance an OXFAM report in 2011 points to the fact that majority of Ghanaians still pay user fees in accessing health care and the situation is even worse among NHIS card holders. The research has shown that the current state of funding the NHIS is not sustainable even though majority of the funds are from the National Health Insurance Levy and 2.5 per cent of VAT on goods and services, a large number of people are not on the NHIS because they cannot afford to pay the annual premium.In the meantime, the most important objective of health insurance is the role it plays in promoting universal protection against financial risk and promoting a more equitable distribution of the funding burden. It is when the sustainable financing policy objectives are in place that other objectives which seeks to promote equitable use and provision of services relative to need; improving the transparency and accountability of the system to the population; promoting quality and efficiency in service delivery; and improving efficiency in administration of financing as suggested by Kutzin in 2008 becomes more apparent.Whiles there is need to either increase the national health insurance levy or explore other sustainable avenues of funding, there is also the urgent need to peg the system of the administrative inefficiencies such as poor payment of premium and membership card administration. There is the need to introduce innovative strategies and cost containment measures that can save the scheme from collapsing. As authorities from other countries visit Ghana to learn from the NHIS experience, which is touted as among the best on the continent, one issue should be the guiding principle; sustainable funding sources are critical to the survival of a universal health insurance scheme. The benefits of health insurance are normally seen in twofold: gains made from avoidance of financial risk by the purchaser and the benefits derived from insurance’s ability to make accessible medical care that would otherwise be financially unaffordable, [28]. What then happens when the purchaser is denied health care because the government owes health providers? That seems to be the state of Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme.Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the staff and members of the National Health Insurance Scheme in the various regions, the staff of the various health facilities who were generous in giving data and the various patients who made time to respond to the questions at those difficult moments.Ethical Issues: Ethical approval was given by the various institutions used in the research.Competing Interests: The author declare that there are no competing interests. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of any governmental agency.

Notes

- 1. Paraceutamol is the commonest and cheapest pain killer in Ghana2. I have changed the names of the victims in order to protect their identity.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML