-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2014; 4(5): 179-184

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20140405.05

Psychological Health of Medical and Dental Students in Saudi Arabia: A Longitudinal Study

Khalid Aboalshamat1, 2, Xiang-Yu Hou2, Esben Strodl3

1Community Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

2Public Health and Social Work School, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia

3School of Psychology, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia

Correspondence to: Khalid Aboalshamat, Community Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction: Many studies have indicated the poor psychological health of medical and dental students. However, few studies have assessed the longitudinal trajectory of that psychological health at different times in an academic year. Aim: To evaluate the positive and negative aspects of psychological health among preclinical medical and dental students in Saudi Arabia prospectively. Methods: A total of 317 preclinical medical and dental students were recruited for a longitudinal study design from second and third-year students at Umm Al-Qura University in the 2012-2013 academic year. The students were assessed at the middle of the first term and followed up after 3-monthes at the beginning of the second term. Questionnaires included assessment of depression, anxiety, stress, self-efficacy, and satisfaction with life. Results: Depression, anxiety, stress, and satisfaction with life were improved significantly at the beginning of the second term, whereas self-efficacy did not change significantly. The medical, female, and third-year student subgroups had the most significant changes. Depression and stress were significantly changed at the beginning of the second term in most demographic subgroups. Conclusion: Preclinical medical and dental students have different psychological health levels at different times of the same academic year. It is recommended to consider time of data collection when analyzing the results of such studies.

Keywords: Psychological health, Medical students, Dental students, Dental education, Depression, Anxiety, Stress, Self-efficacy, Satisfaction with life

Cite this paper: Khalid Aboalshamat, Xiang-Yu Hou, Esben Strodl, Psychological Health of Medical and Dental Students in Saudi Arabia: A Longitudinal Study, Public Health Research, Vol. 4 No. 5, 2014, pp. 179-184. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20140405.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Multiple systematic reviews have reported unfavorable psychological health status among medical and dental students globally [1-4]. This distress has been suggested to negatively affect the students’ health, professional life, and their patients’ safety [5, 6]. Similarly, other measures of psychological health such as perceived stigma have been associated with students’ drop out of medical and dental programs [4, 7] which in turn results in a subsequent reduction in the health care workforce. Many academic factors have been reported to be behind medical and dental students’ poor psychological health, such as a high workload, future study concerns, the long duration of academic days, and a high number of examinations [3, 4, 8, 9]. In addition many students who enroll in medical and dental schools may experience performance pressure in order to do well in their studies due to their desire to satisfy the value of helping others, attain prestigious jobs, and achieve a stable financial future [10, 11]. This might explain the high level of psychological distress that accompanies the elevated percentage of satisfaction among medical students [12]. An investigation into these students’ psychological health should therefore include both the positive and negative aspects of their health in order to achieve more wholistic evaluation of psychological health in this population. The predictors of psychological health in medical and dental students is complex with emerging evidence of moderators of these associations. For example, several studies have highlighted a gender difference in psychological distress levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. These studies have indicated that females were more vulnerable to distress than males [3-5, 13]; however, some studies indicated that there were no differences [14, 15]. In addition, year of study has been as a possible moderating factor with the evidence still being contradictory. For example, some have suggested that the early years were more distressing [5], whereas others have suggested that distress in the students’ last years was greater [4, 16]. Moreover, other studies have highlighted that the discipline being studies may be a moderating factor given that dental students are more distressed [17, 18] and less satisfied than medical students [19]. Despite the high number of publications since 2000 on the psychological health of medical and dental students, most were cross-sectional studies. Only a few longitudinal studies were conducted to assess the changes across time; some found that psychological distress [14, 20] and life satisfaction [21] deteriorated from the first years to the final years among medical students. A study in the United Kingdom found that the psychological distress was transient during the first academic year among medical students and did not persist in subsequent years [22]. Few studies have investigated these changes across the same year. A longitudinal study in Malaysia on first-year medical students indicated that they had higher depression, anxiety, and stress levels at final examination time compared with the beginning of the year [23]. However, such findings were not supported by other literature from other countries; investigations of other years or on dental students have not been reported. Furthermore, no longitudinal study has been conducted into the psychological health of medical and dental students in the Middle East. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the change in the psychological health (positive and negative aspects) of Umm Al-Qura University (UQU), Makkah, Saudi Arabia, preclinical medical and dental students prospectively at different times. It also aimed to identify changes over time in psychological health between different demographic subgroups. It was hypnotized that psychological health at the beginning of terms are better than the middle. It was also hypnotized that different subgroups to act differently.

2. Methodology

- Both medical and dental program at UQU are six-year programs. The students at both faculties study an orientation (1st) year together with other health specialties (such as pharmacy and nursing). After that, medical and dental students study separately for two preclinical (2nd and 3rd) years, followed by three clinical (4th, 5th, and 6th) years. Each year is composed of two terms. Students at both faculties at UQU take multiple quizzes and examination that start from the 4th-6th week of each term and continue, with intermittent periods free of exams, until term’s final exams.

2.1. Design, Sample and Ethics

- A longitudinal study-design was used on the preclinical students at both faculties for the 2012-2013 academic year at UQU. Calculating sample size was done using sample size equation for one group and continues outcome [24]. The following values where used; α=0.05, study power 90%, standard deviation =7 as derived from similar study [25], and clinical difference of 4 points. This resulted in 65 participants as the minimal number of participants needed to detect a difference. Different promotional methods were used (poster and personal invitation) to recruit adequate sample size to avoid bias due to lack of power. Selective sampling was used to included all male and female students at the preclinical years at both faculties (654). The students were invited at week 12 of the first term. The exclusion criteria, that included being under psychological treatment or drugs, were not applied on the students, so all the students were eligible to the study. Reporting this study was compliance with STROBE checklist.

2.2. Study Setting

- Data were gathered using a self-reported hard-copy questionnaire that was distributed and collected by research assistants twice: first (T1) at the middle of the first term (week 12) after days of minor quizzes, followed up after 3 months (T2) at the first week of the second term. T2 was after the students spent one-week vacation between the two terms. Students at T1 or T2 were not taking any exams or quizzes concurrently. The questionnaires were disseminated and collected by research assistants at breaks between lectures. The questionnaires were reviewed and analyzed by the main investigator. Participants were asked to sign a study consent form. Participants were informed that they would have another follow-up questionnaire, their data would have no influence on their relationship with their faculties or the research team, and that the data would be treated anonymously. The 3 months between T1 and T2 was probably sufficient to avoid recall bias. A number of research assistants were allocated and trained to disseminate and communicate with participants in a uniform and organized manner to avoid attrition bias. Ethical approval was obtained from Queensland University of Technology (QUT) in Australia, and from the medical and dental faculties at UQU in Saudi Arabia.

2.3. Outcomes and Instruments

- The self-reported questionnaire assessed the students’ positive and negative psychological health aspects (depression, anxiety, stress, life satisfaction and self-efficacy) using three scales. The first was the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) [26, 27] in its Arabic version [28]. DASS-21 is a 21-question scale that is comprised of 7 questions that are summed for each subscale of depression, anxiety and stress. DASS-21 has good psychometric properties, with reliability coefficients ranging from 0.82 to 0.90 in each subscale [26]. The second was the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) [29], which measures satisfaction with life; an Arabic version employed in a previous study was used [30]. SWLS is a five-question scale that also has good psychometric properties with a reliability coefficient of 0.87. The third was the General Self-Efficacy scale (GSE) [31], which measures self-efficacy within students; this GSE was used in its Arabic version [32]. GSE is a 10-question scale that has been tested in 25 nations and has good psychometric properties, with a reliability coefficient of 0.86. DASS-21 was used to measure the negative aspects of psychological health, whereas SWLS and GSE were used to assess the positive aspects. These instruments have excellent psychometric properties and were chosen to avoid instrument bias. Demographic questions were potential effect modifiers and confounding, and were included for department, gender, year of study, family income, marital status, and nationality.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 21. Frequency tables were generated for the descriptive data. T-test and chi-square test were used to compare between the study participants and the students who dropped out of the study. Paired t-tests were used to analyze the change in depression, anxiety, stress, GSE, and SWLS means between T1 and T2. Subgroup analyses involved using paired t-tests to compare changes between T1 and T2 across faculty (medical/dental), gender, year of study, and family income. Only students who completed the questionnaires at T1 and T2 were analyzed. Level of significance was measured as p< 0.05 for all tests. Students who dropped out of the study at T2 were not included in the statistical analysis of this study. Very few values were missing (overall less than 0.1%). Expectation maximization (EM) method were used to replace missing values.

3. Result

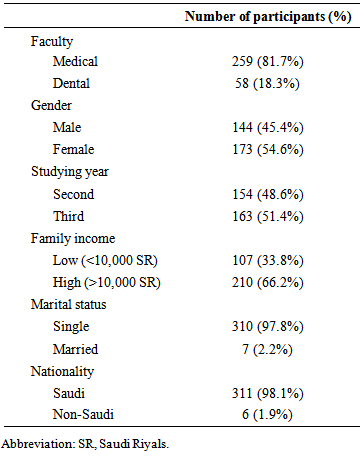

- Only (422) of the invited students accepted to participate, resulting in 64.52% response rate. This might be because the students’ were not willing to participate in a study with follow up, especially when they at study time. Of these, (317) completed the follow-up, yielding a 24.88% dropout rate. The drop out can be explained by the students’ failure to return follow up in the specific time. The 317 students formed the sample size of this study; of these, 81.7% were medical students. Females represented 54.6% and third-year students represented 51.4% of the cohort; 66.2% had a family income of more than 10,000 Saudi Riyals (2,667 USD); only 1.9% were non-Saudi; and 2.2% were married (table 1). The Students’ ages ranged between 20 and 22 years.

|

|

| Table 3. Demographic subgroups associated with depression, anxiety, stress, GSE, and SWLS scores at T1 and T2 in the preclinical years for UQU students |

4. Discussion

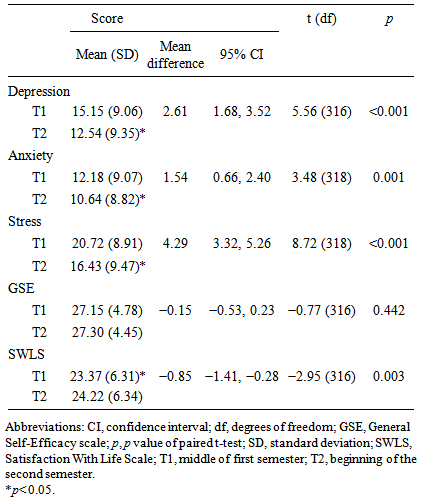

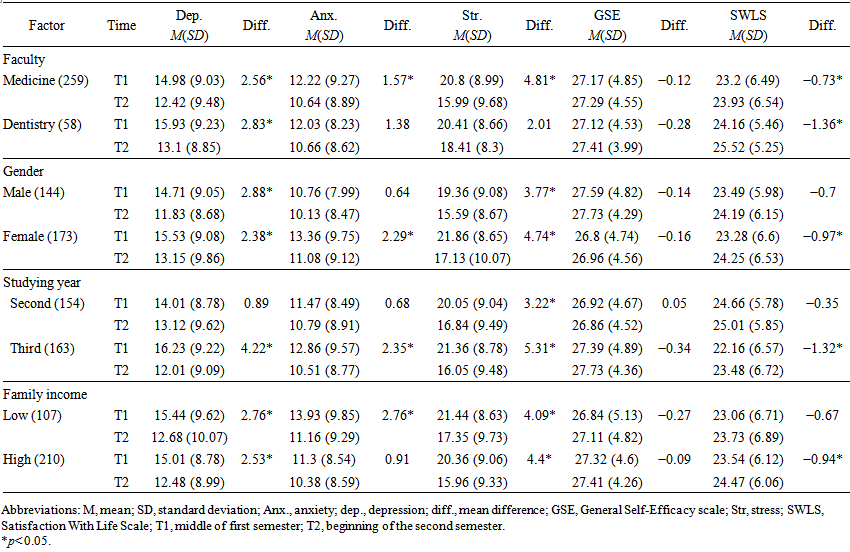

- Depression, anxiety, and stress status were significantly lower at T2 for the students overall, indicating an improvement in the negative aspect of psychological health. This also indicates that students at the middle of years taking classes, exams, and quizzes might manifest a higher distress in compared to beginning of a new term after having one-week vacation. It also agrees with a previous study in Malaysia that finds that depression, anxiety, and stress at the beginning of a term are lower than during or at the end of a term [23]. In addition to the reduction in negative aspect, the students also experienced an increase in satisfaction with life at the start of the second term supporting the view that mid-term vacations are important in rejuvenating university students. On the other hand, general self-efficacy did not change significantly between T1 and T2, and neither was any demographic subgroup associated with significant changes in GSE level. It is therefore possibly the insignificance of our results might be because the short time between the T1 and T2 (3 months) did not provide enough academic experience or time in the course unit to elevate GSE level. More specifically the findings of the study also suggest that there were significant differences in psychological health among the demographic subgroups such as department, gender, year of study, and family income. Neither nationality nor marital status were included in the statistics because of the low number of non-Saudi (6) and married students (7). We identified four patterns in changes in psychological health based on changes in depression, anxiety, stress and satisfaction for life. First, medical, third year, and female subgroups had larger improvements in depression, anxiety, stress, and satisfaction with life between T1 and T2 than dental, 2nd year and male subgroups. Second, several significant results found in medical students were not significant in dental students (e.g. anxiety and stress scores) despite direction of means being consistent across groups. It is likely this is due to differences in sample size of the two groups perhaps rather than anything intrinsic to the groups themselves. However, the presence of persistent anxiety levels among dental students has another potential explanation as UQU Dental Faculty is newly established, meaning there is continuous reform in the curriculum and academic environment that could potentially increase students’ anxiety about unknown challenges. Also, Silverstein indicates in her longitudinal study that stress level changes differently among different dental schools [33] which could be another suggested explanation to our finding in terms of stress. Third, we noticed that second-year students’ psychological health did not improve except in terms of stress levels, while third year students’ psychological health improved in terms of depression, anxiety, stress, and life satisfaction. This might indicate that third-year students suffer from more challenges and distress, as indicated in another study [34]. The significant reduction in stress level in both years can be justified as quizzes and examinations, which might increase students stress especially, are more frequents in the middle of terms than the beginning. Last, depression and stress level were reduced at all the demographic subclasses, unlike anxiety and SWLS. Anxiety and SWLS seem to be sensitive to gender, year of study, and family income. Male and second-year students had no improvement in anxiety or satisfaction levels at T2. In regard to income, low family income students had a significant reduction in anxiety in contrast with high-income students. This might be due to financial burden of expenses during the term. On the other hand, high family income students had a significant increase in SWLS, unlike low family income students. This is may be because high family income students can spend extra money to enjoy their time at the beginning of the year in contrast to low-income students. This study had the following strengths: 1) the prospective study design. 2) There were very few missing data and dropout percentages. 3) There was no demographical or psychological difference between the our sample and dropped out students. Also, 4) The instruments used in this study had good psychometric properties and have been widely used in different cultures.On the other hand, caution needs to be taken in generalizing the results of this study to all preclinical medical and dental students in Saudi Arabia because the study was conducted in UQU only. Participating was based on self-selection and so was not random-based. Also, medical and dental students ratio was not equivalent. However, this was unavoidable due to the low number of dental students positions in compared to medical students in UQU.

5. Conclusions

- The general improvement in our results in psychological health (depression, anxiety, stress, and satisfaction) constructs suggests that the medical and dental students experience different educational environment along the terms. The multiple examinations in the middle of the term is suggested to be an important distressful factor in compare to the beginning of a term. Our results also suggest that the student are rejuvenated by vacation breaks between terms and emphasizes the importance of such breaks in promoting the psychological health of medical and dental students. This also drew an implication on the majority of the cross sectional studies on psychological health among medical and dental students, as the differences in the cross-sectional results might be because of different data collection time. Students with different gender, faculty, financial status and academic year might response differently to each psychological construct. This should be taken in consideration when designing or analyzing future studies on such population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The first author used Queensland University of Technology (QUT) PhD candidature fund in addition to Umm Al-Qura University (UQU) scholarship fund to conduct this study. QUT and UQU had no influence on this study. Authors has nothing to disclose.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML