-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2014; 4(4): 111-116

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20140404.01

Epidemiology of Influenza-like Illness (ILI) in Java Island, Indonesia in 2011

Hartanti Dian Ikawati, Roselinda, Vivi Setiawaty

Center for Biomedical and Basic Technology of Health, National Institute of Health Research and Development, Jakarta, 10560, Indonesia

Correspondence to: Vivi Setiawaty, Center for Biomedical and Basic Technology of Health, National Institute of Health Research and Development, Jakarta, 10560, Indonesia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

In tropical regions, influenza virus activity can occur throughout the year. The aim of this research was to investigate the epidemiology of influenza-like illness (ILI) and the circulation of laboratory-confirmed influenza viruses in Java Island, Indonesia during 2011. ILI cases were analysed based on demographic characteristics (age, sex and origin of site) and we have also assessed patient contact with dead poultry. Numbers of ILI cases differed considerably between the six different sites in Java. Most ILI cases occurred in Semarang (central Java) and the least in Bandung (West Java), with most cases overall reported in children under 5 years of age. ILI was more frequent in males than females. Contact with dead poultry was most commonly observed in adult males and children aged 6-12 years old. Of the ILI cases, 18.72% were confirmed to be positive for influenza virus using molecular detection techniques in the laboratory. Of these, influenza A viruses predominated over influenza type B, with 9.12% of ILI cases A/H3N2 and 5.60% A/H1N1pdm09. No seasonal A/H1N1 or A/H5N1 subtype viruses were detected. Peak A/H3N2 activity occurred in December and peak A/H1N1pdm09 activity in January. Together, these data provide important baseline information regarding the incidence of ILI and the circulation of influenza viruses in different regions of the island of Java.

Keywords: Influenza-like Illness, Java, Indonesia, Seasonality

Cite this paper: Hartanti Dian Ikawati, Roselinda, Vivi Setiawaty, Epidemiology of Influenza-like Illness (ILI) in Java Island, Indonesia in 2011, Public Health Research, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 111-116. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20140404.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Influenza viruses are members of the family Orthomyxoviridae and are divided into three types: A, B and C. Type A and B viruses cause epidemics of respiratory illness which are often associated with increased hospitalization and mortality. Influenza type C viruses cause mild infections and is not a major cause of disease in humans. Poultry is a major reservoir of influenza A viruses. [1]Global influenza surveillance indicates that influenza viruses can be isolated from people throughout the world in all months of the year. In countries with four distinct seasons, influenza occurs most commonly in the winter months. In the northern hemisphere, influenza activity usually occurs between November and March, compared to a peak between April and September in the southern hemisphere. In tropical regions, influenza activity can be observed at any time throughout the year. [1]Epidemiology is the study of distribution anddeterminants of health-related issues in a specified population. [2] Since influenza viruses exhibit high rates of mutation, it is important to understand its epidemiology in order to prepare for epidemics and pandemics associated with this disease.Indonesia is an archipelago which consist of thousands of islands spread along the equator line. Each island has unique geographic and demographic characteristics. Indonesia has a tropical climate with two seasons, a dry season and a wet season. [3] In the wet season, disease associated with a range of microbes, including viruses, often increases in incidence. It has been proposed that in the wet season the humid air facilitates growth and spread of respiratory pathogens. [4] In addition, the combination of poverty, population density and population migration can expedite the spread of respiratory infections. As a result, a number of infectious diseases of the respiratory tract, including influenza, may spread rapidly in countries with these population demographics. [5]Java is one of the major islands in Indonesia. Approximately 60% of the total population of Indonesia live on the island of Java. Therefore, understanding the circulation of influenza viruses in the island of Java is particularly important to gain insight regarding particular types and subtypes of viruses currently circulating and to provide information which may be used to minimize the impact of future pandemics. Influenza viruses are constantly changing due to genetic mutation so it is important to monitor their genetic and antigenic characteristics. In general terms, the total number of influenza-like illness (ILI) cases which arise in a region reflects the circulation of influenza viruses in that region. [6] This study aim at examining the epidemiology of influenza-like illness (ILI) cases in Java Island.

2. Methods

- This study uses ILI surveillance data from National Institute of Health Research and Development (NIHRD) from 6 sites in Java Island including Bandung, Tangerang, Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Semarang and Malang. ILI was defined as presentation with sudden onset of fever (temperature, ≥38.0°C) plus cough and/or sore throat, which was not diagnosed as other diseases. Throat and nasal swabs were taken from patients who met this case criteria by trained health workers at health centers. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) was used to determine the type and subtype of influenza viruses in these specimens by regional laboratories, and results were confirmed by the Virology Laboratory, National Institute of Health Research and Development, Jakarta. [7]The data used in this study comprises (i) demographic data (age, sex, site of origin), (ii) risk factors associated with influenza virus infection, including contact with dead chickens, (iii) monthly of presenting case and (iv) results from real-time reverse-transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assays on clinical specimens. Data was cleaned using STATA to eliminate variables not needed for further analysis. Total ILI cases are presented as a percentage for number of cases for each site. Distribution of ILI cases by sex and age were determined by analyzing variable data including the original site, gender and age of the patient. Age variables are classified into six groups: 0-5; 6-12; 13-17; 18-34; 35-49 and over 50 years. Afterwards, age group and gender was analyzed based on the status of contact with dead chickens. The percentage of ILI positive influenza cases was calculated by using combined data from 6 sites. Cases with no specimens were eliminated. The persentage of ILI positive influenza cases, type and subtype are calculated and presented in tabular form. Monthly distribution of influenza virus type and subtype circulating in Java were also determined.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. The Number of ILI Cases in Java

- 625 ILI cases were recorded in Java during 2011. The highest number of ILI cases occured in Semarang, followed by Malang, Jakarta, Yogyakarta, Tangerang and Bandung, respectively (Table 1). Semarang is located near the sea and is therefore associated with an increased risk of tidal floods. These floods have the potential to promote spread of infectious diseases as residual water remains in pools and puddles for several days. These pools can serve as a reservoir for influenza viruses, especially if contaminated by poultry waste. In Tangerang, Jakarta, Yogyakarta and Bandung the number of ILI cases were markedly less than in Semarang and Malang. In these regions, ILI patients may be treated in hospitals rather than in local health centers and these cases would not be recorded for the purposes of this study.

|

3.2. Distribution of ILI Cases by Ages

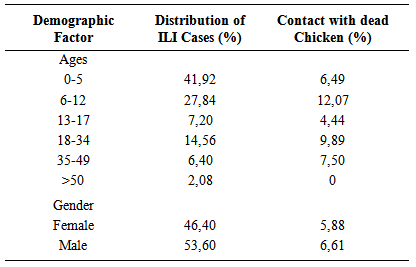

- ILI cases occur in all age groups, mostly among children aged 0-5 and 6-12 years old. The incidence of ILI dropped in 13-17 year olds but increased again in the 18-34 age group (Table 2). Our results are in accordance with previous studies which report that children have the highest rates of influenza virus infection. [13]

|

3.3. Distribution of ILI Cases by Gender

- The number of ILI cases also varied by gender (Table 2). More than half of all ILI cases occured in males. Differences in gender could affect exposure to pathogen, vulnerability to infection, health-seeking behavior and immune responses to pathogens, resulting in differences between males and females in the incidence, duration, severity and case fatality rates following infection. [20]Behavior risk factors such as smoking are more common in males than females. Females have better hand hygiene than males. [20] Simple hygienic behavior such as washing hands has an important role in preventing the transmission of influenza virus and therefore limits influenza disease. According to the WHO survey of 59 countries in 2002-2004 regarding health care access, adult females sought treatment for illness more commonly than males in both low- and high-income countries. [20-21]Males and females also have different roles in society. In Indonesia, males are generally the primary source of income for the family and actively work outside the home whereas females are responsible for taking care of the home and the family. Therefore, exposure to pathogens such as influenza may be more likely in males rather than females.

3.4. Distribution of ILI Cases by the Contact Status with the Dead Chickens

- Children aged 6-12 years old had the highest incidence of contact with dead poultry (Table 2). However, the highest number of ILI cases occurred at the age 0-5 years where contact with dead chickens occurred less frequently (Table 2). Contact with dead poultry is certainly not the only factor affecting the incidence of ILI, although it can be particularly important in the acquisition of A/H5N1 infections. However, the incidence of ILI due to seasonal virus strains is strongly influenced by many different factors including population density and behavior, nutrition, personal and environmental hygiene and pollution. [5]Based on gender, contact with dead poultry occurred more commonly in males rather than females (Table 2). In Indonesia, the practices associated with raising chickens around the home are often performed by the male. These habits increase the risk of avian flu infection. [18] Rural people raise chickens in the yards surrounding the family home and the birds are used for their own consumption or sometimes in cockfights. The chickens are allowed to roam during the day and put into a cage during the night. Larger poultry farms are sometimes located close by and birds may also be sold at nearby markets. When some birds are sick, they are often housed with healthy birds due to space restrictions, which may promote spread of avian influenza viruses. Particular care must be taken when handling chicken products for consumption due to the potential for human infection with avian influenza viruses. Farmers are also advised not to use chicken wastes as fertilizer in their field. [18]

3.5. The Percentage of Influenza Positive of ILI Cases

- Laboratory-confirmed influenza virus was detected in 18.72% of all ILI cases in Java. The low percentage of laboratory-confirmed cases likely occurred due to misinterpretations related to case definition as a number of patients presented with body temperatures of < 38℃, often as the result of reduced temperature due prior consumption of medicine before visiting the health center. In 2012, the ILI case definition follows the WHO guideline, hopefully the number of positive influenza will increase. [22] Recent study in Cambodia found that surveillance for acute fever provide a significant increase in the number of influenza patients identified. [23]

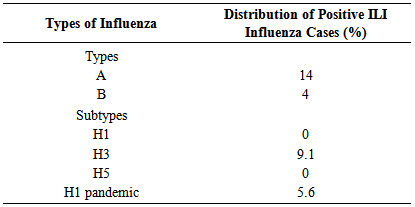

3.6. Frequency of Types and Subtypes of Influenza

- Of the laboratory-confirmed influenza cases, type A was detected more frequently than type B viruses (Table 3). Of the type A viruses, the H3 subtype was detected more frequently than the H1pdm09 subtype. Seasonal H1 and H5 subtypes of influenza A virus were not detected in this study (Table 3). H5 cases are often associated with severe symptoms and require specialized hospital treatment. Since data for our studies was derived only from health centers, the possibility to detect acute H5 cases was small. Previous reports indicate that clinical symptoms associated with H3 subtype infections can be more severe than those associated with H1pdm09 infections. [24] If this were true, the mild clinical symptoms associated with H1pdm09-infected people in our study may mean that they did not seek treatment. This could be a factor contributing to the low H1pdm09 incidence in our study.

|

3.7. Monthly Distribution of Influenza Cases

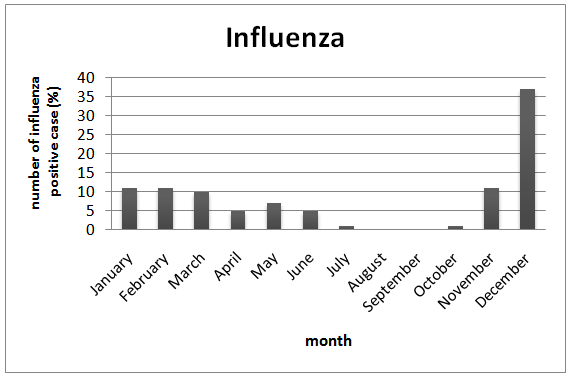

- Monthly distribution of influenza in Java fluctuates throughout the year. At the beginning of year the incidence of laboratory-confirmed influenza increases, then declines such that influenza was not detected in August and September. Confirmed cases appeared again in October, rose significantly in November and reached peak activity in December. In January, February, March and December, the number of ILI cases increased more than the average of ILI cases. (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Java’s Monthly Activities of Influenza Cases in 2011 |

3.8. Monthly Distribution of Influenza Virus Subtypes

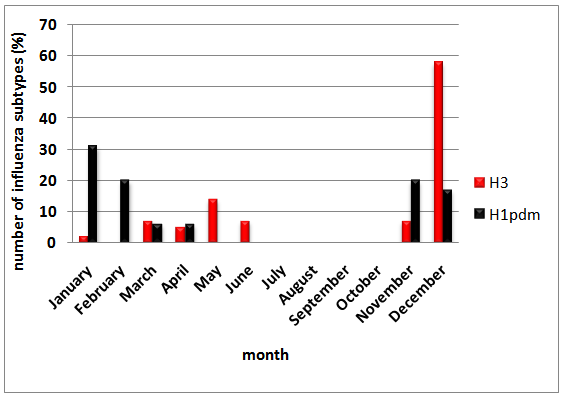

- H3 subtype influenza A viruses were most commonly detected in December, whereas the number of laboratory-confirmed cases of H1pdm09 peaked in January (Figure 2). These data correspond with data from Flunet [27], showing that H3 is the predominant subtype circulating in Indonesia in 2011, appearing at the end of year and that H1pdm09 was the predominant virus circulating at the beginning of year.

| Figure 2. Java’s Monthly Distribution of Influenza Virus Subtypes in 2011 |

4. Conclusions

- We have analysed ILI cases from 6 different regions in the island of Java, Indonesia during 2011 and report marked differences in the incidence of ILI between these sites. The highest incidence was recorded in Semarang and the lowest in Bandung. ILI cases occurred in all age groups, but most commonly in children aged 0-5 years old. Males tended to suffer ILI more frequently than females. At the age of 6-12, children reported the most frequent contact with dead chickens. 18.72% of the total cases of ILI were confirmed to be positive for influenza via laboratory testing using a rRT-PCR assay with type A viruses detected most commonly. Of the type A viruses, A/H3 and A/H1pdm09 were detected, but not A/H1 or A/H5, with A/H3 viruses detected more commonly. The monthly distribution of ILI cases in Java shows the highest incidence at the start (Jan/Feb) and end of the year (Nov/Dec) with little activity during the middle of 2011 (July – Oct). A/H3 showed high incidence in December, whereas A/H1pdm09 peaked in January.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author would like to thank to Rabea Pangerti Yekti, DVM, MPH for the guidance during the writing process of this scientific papers. Many thanks to Virology laboratory team for the good work and collaboration. Thanks to the District Health Officers and Doctors and Nurses in the Primary Health Centres for the continuos contribution for the Influenza surveillance in Indonesia. The authors that Dr. Patrick Reading from the WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza, Melbourne, Australia for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML