-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2014; 4(3): 98-103

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20140403.04

Empowering Non-family Caregivers of Older Adults in Macao Chinese Society: Combining Theory Knowledge Lesson and Basic Care Skill Laboratory

Cindy Sin U Leong1, Lynn B. Clutter2, Mei Wai Ho3

1School of Health Science, Macao Polytechnic Institute, DHSc, MHS (Gerontology), BSN

2The University of Tulsa, Oklahoma, United States of America, PhD, APRN, CNS, CNE

3University Hospital, Macao, BSN

Correspondence to: Cindy Sin U Leong, School of Health Science, Macao Polytechnic Institute, DHSc, MHS (Gerontology), BSN.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The objective of this study was to empower non-family caregivers’ with regards to knowledge and important basic-care skills of dependent older adults at home in Macao Chinese society. A mixed method study with qualitative measure and quantitative descriptive were conducted over four months. Twenty-five non-family caregivers were purposely selected to participate in a teaching and training class related to general elder care topics. All non-family caregivers (NFCs) provided care services to older adults. Caregivers completed a pretest and posttest before and after the teaching and training class. A primary quantitative finding was that the mean difference between pretest and posttest scores was 25.79 with a 95% confidence interval between 8.78 and 42.80. T-test showed that the difference between two means was significant (t = 4.210, df = 4, p = 0.01, 2-tailed). A qualitative assessment (N=3) identified themes of education for non-family caregivers is essential to support home-based older adult care with higher quality of life outcomes for older adults.

Keywords: Older adult care, Non-family caregivers, Knowledge and skill

Cite this paper: Cindy Sin U Leong, Lynn B. Clutter, Mei Wai Ho, Empowering Non-family Caregivers of Older Adults in Macao Chinese Society: Combining Theory Knowledge Lesson and Basic Care Skill Laboratory, Public Health Research, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2014, pp. 98-103. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20140403.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- There has been a recent and alarming global increase in the older population. This is due to declining fertility and improvements in health and longevity. There will be an estimated 2 billion adults over 60 by 2050 [1]. This trend is especially true among the Baby Boomer generation. By 2035, adults over the age of 65 years will account for 1 in 5 persons [2]. An estimated 13% of the US population is over age 65, accounting for 38.9 million American residents [3]. It is expected that there will be 72 million older people by 2030 and the percentage of elderly will be approximately 17% in the US [3]. In European countries such as the UK, the number of older adults over 65 reached 17% in 2010, accounting for 1.7 million people [4]. It is predicted that by 2033, the proportion of adults over 65 will reach 23% of the UK population [5]. The number of people aged 85 and over was 1.4 million in mid-2010. Men make up approximately 37% of the adults aged 85 and over and women take up the remaining 67% [6]. Older people are the primary users of social care resources. Older women in particular are more likely to be admitted to a residential home [7]. Of older adults using government-funded live in residential or nursing homes, 77% are aged over 65 and 65% of these consume community-based social care [7]. It is well-known that the World Health Organization originated the concept that the best place for older adults is their own-“home” as the older adults have loved ones and are familiar with the surrounding area [13]. With regards to this development of well-being for the aging population, the local government has the responsibility to use health policy strategies to assist older adults to remain in the community as long as they are capable and willing.According to the [8], aging in place is defined as the freedom and right to live with a level of independence in one’s own home with the community provision of safe environment and easily accessible transportation, social support such as home care service as well as inexpensive nearby primary health services. When it is possible for older people to stay in their home and community longer, institutional time and financial requirements decline and older people and their family members have higher levels of satisfaction [9]. A research report announced by the State Survey of Liveability Policies and Practices showed that 90% of the aging population prefer to stay at home [9]. In reality, approximately 5% of older adults reside in nursing homes (skilled care facilities) [10]. There is a report showing that almost 80 % of adults over aged 50 prefer to stay in their own homes as they age [11]. This implies that with increasing numbers of older adults, the number caregivers needed will increase. Older adults benefit from periodic assistance in living activities regardless of health status. Given the shortage in older adult day care centres and nursing homes, care of this nature is primarily from non-family caregivers in much of the world. Additionally, in Chinese and other cultures older adults consider nursing homes to be for older adults who have been abandoned or have a “lack of love” by their adult children. In addition, adult children may feel bad by putting their elderly parents in nursing homes. Traditional Chinese and a variety of other cultures assume that the care of older adults is the responsibility of other family members. Older parents being cared for in nursing homes can feel inferior and even shamed in these cultures. However, for the most part only older adults who do not have children or any close relatives would prefer to stay in nursing homes [12]. In other cultures and situations, older adults prefer to stay in facilities that can meet their needs more suitably than family members can. Some facilities have various levels of care but only accept residents at a point of independent or assisted living status. Then with health status changes, residents can change to units with greater health care or specialty units such as Alzheimer care units. This type of advanced gerontology care is not available worldwide and can be quite expensive.The quality of nursing homes is variable, even for expensive facilities. The better the quality of the nursing home, often the longer the wait time is for availability. Some nursing homes require a wait time exceeding several years as there are no vacancies for new occupants until an occupant passes away. As an example, one well-qualified nursing home in Macao has had no vacancy for females since it opened to the public (1999).Even with well-organised established nursing homes facilities, the cost may be prohibitive for the older population. In addition, some believe that autonomy, feelings of security, self-esteem, bonding, identity and other issues important to older adults are difficult to maintain in such facilities [13]. Other older adults feel that their facility provides greater opportunity to grow in these areas than would a home environment. Even with the existing status of residential care in various countries, there is a great need for quality non-family caregivers who are sensitive to the unique needs of older adults.In Macao, these caregivers mostly originate from the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam. According to the information, the household of the family in Macao is 7.8%. There are total of 15,874 non-family caregivers caring for local residents [14]. Interventions can encourage their enthusiasm for their work by increasing their knowledge and basic-care skills for caring for older adults. One unique advantage is that with taxation revenues, all Macao permanent residents over 18 years old can receive $625USD for continuing education within any 3-year period. Mostly, older adults did not use the subsidised funding for continuing education. Therefore, these funds may be used for training courses for their non-family caregivers to enhance knowledge and skills needed in care of the older adults.According to the theory of “aging in place”, caregivers are required for assistant when older adults reach 85 years. In Macao, also some older adults require assistance even at age 65 or 75. Those with chronic illnesses including common diagnoses such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and arthritis may require from NFCs at younger age. Caregivers who are familiar with the daily habits of older adults such as eating style, sleep patterns and daily activities are more effective in their care. Those who have specialized knowledge in the needs of older adults can be more effective in enhancing the quality of life for those in their care.Macao, a moderately sized city of 600,000 residents who are predominantly Chinese (97%), is approximately 30 km2 in size (Statistics & Census Service 2013), and is located in the southern part of Guangdong Province. There are approximately 44, 000 older adults over 65 years of age. Macao has a total of 1109 hospital beds (Health Statistics, 2011). The population has an average life expectancy of 84.7 years, but only 7.9% of the population is over the age of 65 years. For every 1000 residents, there are 2.6 physicians, 2.9 registered nurses (RNs) and 1.0 traditional Chinese medical doctors. The ratio of RNs to residents is 1: 460 in Macao which is far below the ratio of other countries. In addition, there are eighteen elderly nursing homes in Macao providing 1200 beds for elderly who are unable to take care of themselves. Therefore, many elderly are cared for by non-family caregivers. Increasing the basic care and knowledge of caregivers for older adults might hope to decrease or delay the admission to nursing homes or hospital and is a worthwhile nursing contribution to advance the care of older adults.The aim of the educational workshop was to advance caregiver knowledge about typical changes, physical and psychosocial issues in older adults. Through an educational workshop presented by nurses, caregivers would be more aware of abnormal signs and symptoms in the elderly, and would demonstrate earlier reporting to prevent any delays in treatment. The quantitative study aim was to evaluate changes in pre- and post-test findings of non family caregivers (N=25). The qualitative study conducted prior to the educational workshop had an aim to identify unique older adult need priorities and felt-needs of the NFCs in their caregiving.

2. Methods

- Considering the frequency of acute hospital readmissions, the authors aim to explore this issue. Therefore, interviews of frontline nursing staff in acute and emergency centres, medical wards and senior day-care centres were conducted. The combination of qualitative and quantitative methods helps to reinforce the findings. A qualitative approach explores real life experiences from a multidimensional stand-point. A quantitative approach has the ability to measure and assess solutions. In this study, both qualitative and quantitative approaches were applied to empower non-family caregivers. Qualitative data were collected through interviews with randomly selected nursing staff and caregivers during daily care in wards and homes.There are two major objectives of this study:To investigate the major inadequacies in knowledge among nursing staff and non-family caregivers of older adults.To assess whether the non-family caregivers benefited from the educational workshop based on pretest and posttest measures.

2.1. Qualitative Method

- Qualitative data were collected using semi-structured interviews with selected participants from the medical and emergency wards and senior centres prior to the workshop. The choice of participants for these interviews was guided by nurses’ familiarity older adults’ admission to these facilities. To compare and contrast with the findings from the professional nurses, non-family caregivers of older adults were also randomly selected for interviews. A total of 5 participants were recruited and oral consent was obtained from them. All participants were volunteers and understood that they could withdraw at any time during the interview. Participants were also informed that subsequent publications would keep maintain their anonymity and confidentiality. All the main points were recorded and the accuracy and truth of the accounts were verified.

2.2. Quantitative Method

- A total of 25 non-family caregivers registered for the workshop. Information regarding normal age-related changes was provided during the five sections of workshop. The last section of the workshop was carried out in a nursing laboratory, with the authors demonstrating basic-care skills. The educational interventions were composed of classroom teaching for non-family caregivers regarding normal age-related changes in older adults. There were 5 classes, each 2 hours in length, providing basic knowledge about the cardiovascular system, respiratory system, pain management, safe environments, nutrition and communication skills. The normal and abnormal situations for each of the topic were covered. Some obvious and significant signs and symptoms for each covered topic were presented. There was subsequently a 2-hour laboratory demonstration of basic skills in assessment and interventions for care of older adults including proper bed rest positioning, transfers and from wheelchair to bed, assistance with eating in a sitting position and so on.

2.3. Other Measures

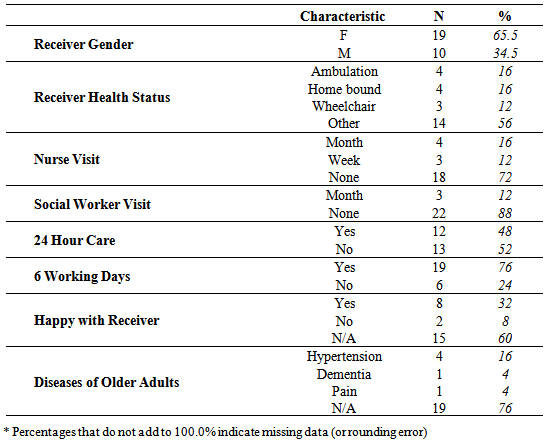

- For all the sections, a pretest before and posttest after the workshop were performed. Five major topics were covered: skin integrity, the cardiovascular system, the respiratory system, digestion and safe environment precautions. Basic, daily problems and experiences were discussed and shared during the workshop. Simple basic nursing care skills such as transfer an older adult from a bed to a chair, the comfort lying position for bed-bound older adult, and the proper position for feeding. The details of the participants are presented in Table 1 below.

|

3. Results

3.1. Results from Qualitative Data Analysis

- A total of 3 nursing staff and 2 non-family caregivers participated in the interviews. The three interviews with nursing staff were conducted at the end of their shifts while the interviews with caregivers were performed during their day off from work. Two questions posed to the nurse participants were: “What are the most frequent causes for admission of older adults to the hospital and what type of information should be provided in the workshop for non-family caregivers of older adults?” During initial recruitment discussions, the 3 nursing staff members consented to give suggestions on important issues for the educational workshop. The 2 caregivers were asked what they faced during caregiving and what they most preferred to learn in the workshop. Important points were recorded and reviewed with the interview participants for verification of accuracy. Descriptions provided by the nurses and non-family caregivers are given below.“They were mostly admitted to my ward because of dehydration mostly. The caregivers did not encourage the older adults to drink more water. Some older adults may not like to drink water because of resulting nocturnal urination”. (Participant 1)“A new caregiver is not familiar with the older adult. She thinks the older adult typically eats less, so she does not match her cooking style to her older adult’s taste”. (Participant 2)“Caregivers need to be familiar with the basic signs and symptoms of high blood pressure, and not wait until the older adult gets worse before reporting the signs or symptoms to their adult children”. (Participant 3)“I would like to improve my communication skill with my client and would like to learn some basic daily caring techniques for older adults”. (Participant 4)“I like to expand my age-related knowledge. My previous client was a 95-year old woman who was bedbound. I provided all of her care”. (Participant 5)

3.2. Results from Quantitative Data Analysis

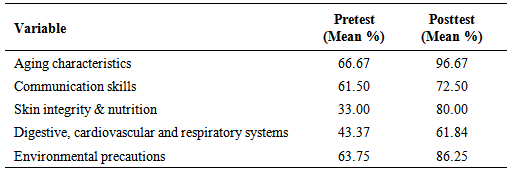

- The non-family caregivers mostly cared for female older adults who were home bound and wheelchair bound (16% and 12%, respectively). In addition, less than 20% of the older adults have regular (monthly or weekly) visits from nursing staff or social workers at home. 48% of the non-family caregivers needed to provide 24 hour care six days per week. It was noted that 24% of the older adults have chronic health problems. Thirty-two percentages of the non-family caregivers were happy with their older adult client. There were 5 administrations of pretest and posttest assessments associated with the five 2-hour classes. The pretest was conducted before the educational session and the posttest was administered after the class. The mean difference between pretest and posttest scores was 25.79 with a 95% confidence interval between 8.78 and 42.80. T-test showed that the difference between the two data sets was significant (t = 4.210, df = 4, p = 0.014, 2-tailed). The effect size (Table 2) showed that the education intervention designed to address gaps in caregiver knowledge is effective.

|

4. Discussion

- There are many research studies exploring caregivers’ attitudes and gaps in knowledge. When the spouse or partner is the care recipients, caregivers would like to provide the best care possible. However, with inadequacies in knowledge and skill, care does not meet the standards necessary to assess symptoms across the disease state and treatment process [15, 16]. However, the spouse or partner is typically no longer young themselves. They may have chronic illness or be very frail. A study shows that caregivers have very limited knowledge about schizophrenia [17]. The caregivers even blamed the care-recipients because of their lack of understanding of the symptoms induced by the illness. There are studies demonstrating that caring for a recipient with dementia takes approximately 10 years. The process will be more relaxed and comfortable if the caregivers have some basic knowledge and information related to the consequences of the progression of dementia [18]. The caregivers will be more patient in their care. With adequate knowledge and skills, family members are happy to see their loved ones cared for by qualified non-family caregivers. The training course to provide knowledge and skills for daily care activities for non-family caregivers is necessary. With inadequate knowledge and skill, non-family caregivers may worry that they are not caring well for the older adults, who may worsen physically and psychologically [16]. This unfamiliar condition may lead to hospital readmission and put the older adults in dangerous situations. Recent studies conducted in China show that an improved knowledge of bedsore precautions is helpful for caregivers who care for older bed-bound or wheelchair-bound adults [19, 20]. It is possible to not only reduce the hospital admission costs but also to increase the satisfaction of older adults and family members.Care at home is preferred by older adults [21]. However, studies show that spousal caregivers often are no younger than their partners. Their ability to provide care to spousal recipients is greatly dependent upon their own cognitive and physical status. These elderly caregivers may have decreased abilities to adapt to provide prolonged and stressful care [22]. There are many studies demonstrating that older adults have difficulties adapting and may face risky situations in new environments, such as with new caregivers or in a new living area. Even non-family caregivers may have a hard time adapting to their new work environment, causing great distress, burnout and job dissatisfaction [23]. With adequate knowledge and skills for daily care, non-family caregivers may be able to work for longer periods of time which could benefit older adults who would not have to adapt to multiple new caregivers. Furthermore, health professionals may schedule their weekly visits to assess the older adults’ health status which may provide support for the stress of caregiving. Regular home visits by health professionals to care recipients and to caregivers can decrease rates of admission to care homes by provision of practical, mental, and informational support [12].Educational workshops on common basic topics could make caregivers more aware of some abnormal developments in the elderly, enabling the caregivers to report these developments as soon as possible, preventing any delay in treatment. Over the long-term, the cost of admission to nursing homes will hopefully decline. Older adults will be more content living with their family members. Recently, the Chinese government announced that older adults should be regularly visited by their adult children, and if not, the adult children may be fined. Therefore, with skilful and knowledgeable non-family caregivers, older adults do not need to end up in nursing homes. Older adults are happier and healthier in their familiar communities and environments. They can go window shopping and to the park every day. There are undoubtedly psychosocial and spiritual benefits. They can often meet with their old friends, old neighbours and relatives with the assistance of caregivers. Therefore, it is necessary to empower caregivers to give support to not only the older adults but also the family members. The manpower and resource burden will be reduced in the long term.LimitationDespite initial useful findings from the study, quite a few limitations must be mentioned. First, the small sample size of participants may decrease the study’s statistical power and lead to non-significant findings. The study sample must be increased for improved data analysis as the workshop continues to evolve. Secondly, it is difficult to predict whether the effects of the empowerment in knowledge and skills will be sustained long term. It is also uncertain whether the recognition of common signs and symptoms of the chronic illness will be applied, and whether the rates of hospital admission will decline. Hence, long-term outcomes of the older adult clients of the participants must be studied. Third, the posttest measurements were performed right after each workshop intervention was completed, reflecting recent memory recall. The impact of the education workshop on the quality of care for older adults is not measured as there was no follow up the older adults cared for by the participants. In future studies, feedback from the older adults and measures of their quality of care must be included.

5. Conclusions

- Empowering non-family caregivers is very important. It not only reduces the chances for hospital admission due to improved recognition of signs and symptoms but also increases physical and psychosocial support for the older adult clients. Older adults can adjust and manage their daily activities with the assistance of non-family caregivers. Some older adults can exercise in the morning with their companion. Consistent contact with neighbours and friends either in the park or at the senior activity centre helps them to remain social and share their life events. The theory of aging in place may work well for frail older adults with non-family caregivers. Thus, healthcare policy makers will also benefit from this study, particularly as they make decisions regarding community health care services.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Authors would like to thank the Caritas Macao allowing conducting the case study as well as appreciating the participants spending their valuable time for completing the training course.

References

| [1] | World Health Organization (2012). Good health adds life to years: global brief for world health day 2012. World Health Organization. |

| [2] | United Nation (2012). Population Facts No. 2012/4, December 2012 - Population ageing and development: Ten years after Madrid. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/develop ment/desa/population/publications/factsheets/index.shtml, accessed 10 June 2013. |

| [3] | US Census Bureau (2010). Projections of the population of the United States: 1997 to 2050. In: current population reports. Profile America Facts for Features. CB10-FF.06. Available at: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb10-ff06.html, accessed 1 June 2013. |

| [4] | Age UK (2013). Late Life in the United Kingdom: August 2013. Available at: http://www.ageuk.org.uk/Documents/ EN-GB/Factsheets/Later_Life_UK_factsheet.pdf?dtrk=true, accessed 5 May 2013 |

| [5] | Office for National Statistics (2010). Annual mid-year population estimates, 2010. Statistical Bulletin. United Kingdom, Theme Population date 30 June 2011. Release: Population estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, Mid-2010. Available at: NationalpopulationprojectionONS.pdf, accessed 10 June 2013. |

| [6] | Office for National Statistics (2011). Detailed Characteristics for England and Wales, March 2011. Statistics Bulletin. United Kingdom, Theme People and places date 16 May 2013. Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011- cesus/detailed-characteristics-for-local-authorities-in-england-and-wales/stb---detailed-characteristics-for-england-and-wales--march-2011.html#tab-Key-figures, accessed 13 June 2013. |

| [7] | McCann, M., Donnelly, M. & O’Relly, D. (2012). Gender differences in care home admission risk: partner’s age explains the higher risk for women. Age and Ageing 41, 416-419. |

| [8] | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011). Aging in place. Healthy Places Terminology, Healthy Places. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ healthyplaces/terminology. htm National, accessed 15 May 2012. |

| [9] | Farber, N., Shinkle, D., Lynott, J. (2011). National Conference of State Legislatures and the AARP Public Policy Institute (2012). Available at: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ ppi/liv-com/ib190.pdf, accessed 15 June 15 2012. |

| [10] | Mynatt, E., Essa, I. & Rogers, W. (2000). Increasing the opportunities for aging in place. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/showciting?cid=111746, accessed 5 May 2013. |

| [11] | Oberlink, M.R. (2008). Opportunities for creating livable communities: center for home care policy and research, visiting nurse service of New York. AARP Public Policy Institute. Available at: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/2008_02_communities.pdf, accessed 1 July 2013. |

| [12] | McCann, M., Donnelly, M. & O’Relly, D. (2011). Living arranagements, relationship to people in the household and admission to care homes for older people. Age and ageing 40, 358-363. |

| [13] | Wiles, J. L., Leibing, A. & Guberman, N. (2012). The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. The Gerontologist, 52(3), 357-366. |

| [14] | Macao Daily Times (2011). Over 75,000 imported workers in MSAR. Available at: http://www.macauhr.com/resource/ 2011-01-15/Over-75,000-imported-workers-in-MSAR/1552, accessed 12 July 2013. |

| [15] | Alemseged, F., Tegegn, A., Haileamlak, A. & Kassahun, W. (2008). Caregivers’ knowledge about childhood malaria in Gilgel Gibe field research center, southwest Ethiopia. Ethiopia Journal Health Development 22(1), 49-54. |

| [16] | Given, B., Given, W., Sikorskill, A., Jeon, S. & Sherwood, P. (2006). The impact of providing symptom management assistance on caregiver reaction: results of a randomized trail. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 32(5), 433-443. |

| [17] | Harrison, C.A., Dadds, M.R. & Smith, G. (1998). Family caregivers’ criticism of patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 49(7), 918-924. |

| [18] | Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K., Dura, J., Speicher, C., Trask, J. & Glaser, R. (1991). Spousal caregivers of dementia victims: longitudinal changes in immunity and health. Psychosom Medical 53, 345-362. |

| [19] | Yang, X. T., Deng, J., & Wu, H. (2008). Analysis of the influencing factors of burden of caregivers in inhabited aged people. Modern Prevents Medicine 35(14), 2700-2701. |

| [20] | Zhou, D. M. Qian, X. L., Lu, M. M. Jia, S. M. & Sun, X. C. (2011). Investigation on the caring behaviors and its influencing factors among family caregivers of patients with pressure ulcer. Chinese Journal Nursing 46(4), 378-381. |

| [21] | Ieong, S.T., Cheang, G., Ng, F., Wang, Y., Fong, C.L., Jiu, G.M.E. & Wang, N. (2008). The burden of home caregivers’ impacts and analysis. Modern Preventive Medicine (In Chinese) 35(14), 2700-2701. |

| [22] | Vugt, M.E., Jolles, J., Osch, L.V., Stevens, F., Aalten, P., Lousberg, R. & Verhey, F.R.J. (2006). Cognitive functioning in spousal caregivers of dementia patients: findings from the prospective MAASBED study. Age and Ageing 35, 160-166. |

| [23] | Given, B., Given, W. & Sherwood, P. (2012). Family and caregiver needs over the course of the cancer trajectory. Journal Support Oncology. |

| [24] | Health Statistics (2011). Government of Macao special administrative region. Available at: http://www.dsec.gov. mo/getAttachment/32d8a6b5–0253–4e9b-bd6a-34eccb4197 d6/E_SAU_PUB_2009_Y.aspx, accessed 26 April 2014. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML