-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2014; 4(3): 79-84

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20140403.01

Continuity of Social Interaction and Functional Status: A Nine-year Population-based Prospective Study for the Elderly

Bailiang Wu 1, Emiko Tanaka 1, 2, Kentaro Tokutake 1, Taeko Watanabe 3, Yukiko Mochizuki 1, Lian Tong 4, Ryoji Shinohara 5, Yuka Sugisawa 6, Yuko Sawada 7, Sumio Ito 8, Rika Okumura 8, Tokie Anme 1

1Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan

2Research Fellows of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan

3Japan University of Health Sciences, Satte, Saitama, Japan

4School of Public Health, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

5Department of Research Interdisciplinary Graduate School of Medicine and Engineering, University of Yamanashi, Yamanashi, Japan

6Ushiku City, Ibaraki, Japan

7Department of physical therapy, Morinomiya University of Medical Sciences, Osaka, Japan

8Department of public welfare, Tobisima, Aichi, Japan

Correspondence to: Tokie Anme , Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

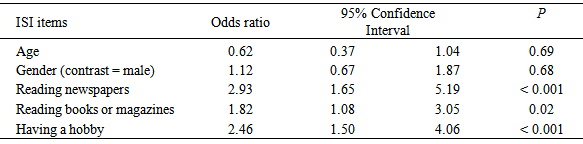

Since the dimensions of social activity have not been described comprehensively in detail and whether the continuity of activity effectively protects functional status over the long term were not clear, this study was designed to clarify the association between continuity of social interaction and functional status in a group of elderly people with a social interaction measure. The participants were elders (n=363) over 60 years old living in a rural community close to major urban centres in Japan. The content of the questionnaire included a social interaction measure named Index of Social Interaction (ISI) that developed for evaluating social interaction of various types, Lawton-Brody IADL, age, and gender. Subjects consisted of 147 males with a mean age of 68 (SD = 5.7) and 216 females with a mean age of 68 (SD = 5.4). The continuity of social interaction was examined by data analysis. During a nine-year follow up, after controlling for elders’ age and gender, the consistent social activities significantly related to their future functional status included: “reading newspapers” (odds ratio (OR) = 2.93, P < 0.01), “reading books or magazines” (OR = 1.82, P = 0.02), and “having a hobby” (OR = 2.46, P < 0.01). The findings indicated that consistent social interactions involving intellectual activities and hobbies were effective in protecting elder’s functional status.

Keywords: Elder, Functional status, IADL, Social interaction

Cite this paper: Bailiang Wu , Emiko Tanaka , Kentaro Tokutake , Taeko Watanabe , Yukiko Mochizuki , Lian Tong , Ryoji Shinohara , Yuka Sugisawa , Yuko Sawada , Sumio Ito , Rika Okumura , Tokie Anme , Continuity of Social Interaction and Functional Status: A Nine-year Population-based Prospective Study for the Elderly, Public Health Research, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2014, pp. 79-84. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20140403.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Consistent with the global trend, countries in the Asia-Oceania region face serious, rapid aging of the population. Japan is typical in that advances in the social and medical fields have improved life expectancy [1]. With the longer life span and decreasing birthrate of an aging society, social engagement of elders has become an important issue and attracted considerable interest regarding its association with cognition, functional status, and affect [2-6].Existing studies have demonstrated that engagement in social activities may contribute positively to a person’s functional status. Previous studies have shown active participation in community events has a positive association with the maintenance of functional status among older people [7, 8]. Other studies also showed that lower social interaction related to cognitive activity was associated with functional status decline [9, 10]. Studies with older people living in urban communities reported that baseline levels of social roles and intellectual activities significantly predict new onset of disabilities in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) during follow-up periods [11, 12]. In summary, it can be inferred that a high level of engagement in social activity is positively related to older people’s functional status.Despite this inference, several issues are not clear. The dimensions of social activity have not been described comprehensively and in detail. There are few studies using specific tools to measure social activity; rather, most collected such data simply as one part of their research. To completely describe a person’s social activity, appropriate measuring tools are required. Another issue is whether the continuity of activity effectively protects functional status over the long term. Previous studies found that having one social activity could contribute positively to functional status, but there is insufficient global evidence for the effects of continuity of social activity.To address these issues, a nine-year follow-up study was completed to clarify the association of continuity of social activity, using a specific measuring tool for social activity and IADL for functional status. This study was expected to provide evidence to understand the association between elder’s functional status and their social interactions in daily life.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

- A longitudinal study (Tobisima study) was carried out with a sample of people living in the rural community of Tobisima, Japan, which has a population of 4,688 and where 14.6% of residents are engaged in the primary sector industry. This study examined factors related to elder longevity in order to improve the health program to maximize the quantity and quality of life for all residents. All residents agreed to participate in this study. A total of 549 elders over age 60 with independent functional status were enrolled in 2002. After nine years, 363 persons, including 147 males with a mean age of 68 (SD = 5.7) and 216 females with a mean age of 68 (SD = 5.4) were still in the study until 2011, resulting in a response rate of 66.1%.

2.2. Social Interaction

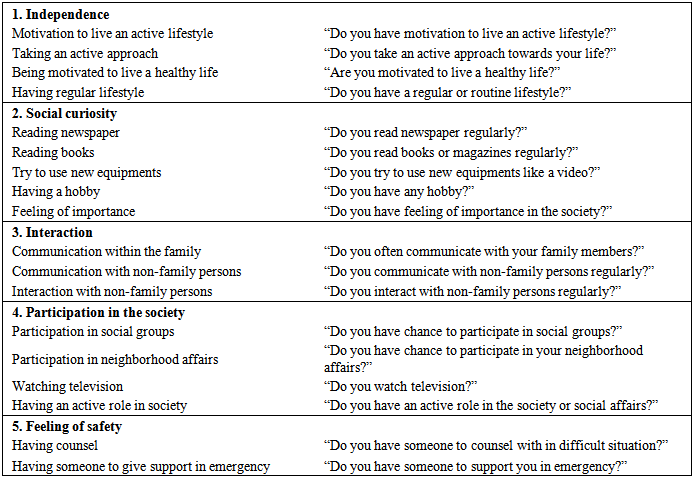

- The social interaction of residents was measured by the Index of Social Interaction (ISI). This scale was developed for evaluating social interaction of various types [13]. There are 18 items in this scale, classified into five subscales: 1)“Independence” measures motivation to live an active lifestyle, taking an active approach towards life, being motivated to live a healthy life, and having a regular or routine lifestyle; 2) “Social curiosity” is composed of reading newspapers, books, or magazines; trying to use new equipment; having a hobby; and having a feeling of importance; 3) “Interaction” includes communication within the family, communication with non-family persons, and interactions with non-family persons; 4) “Participation” in society includes participation in social groups, participation in neighbourhood affairs, watching television, and having an active role in society; and 5) “feelings of safety” is comprised of having counsel, and having someone to give support in an emergency. Cronbach’s alpha for the subscales ranged from .78 to .81. The score of each item was rated one point for a positive response (e.g., “yes, I do” or “yes, I have this”) and zero for a negative response. The 18 items of ISI and corresponding questions are presented in appendix 1.

2.3. Functional Status

- The Lawton-Brody IADL Scale was introduced to measure the functional status of elders, including the ability to use a telephone, shopping, food preparation, housekeeping, laundry, model of transportation, responsibility for own medications, and ability to handle finances [14]. Positive responses mean the elder can engage in instrumental activities of daily living. Functional status score was calculated by summing each positive response point and a higher IADL score denotes a better functional status.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

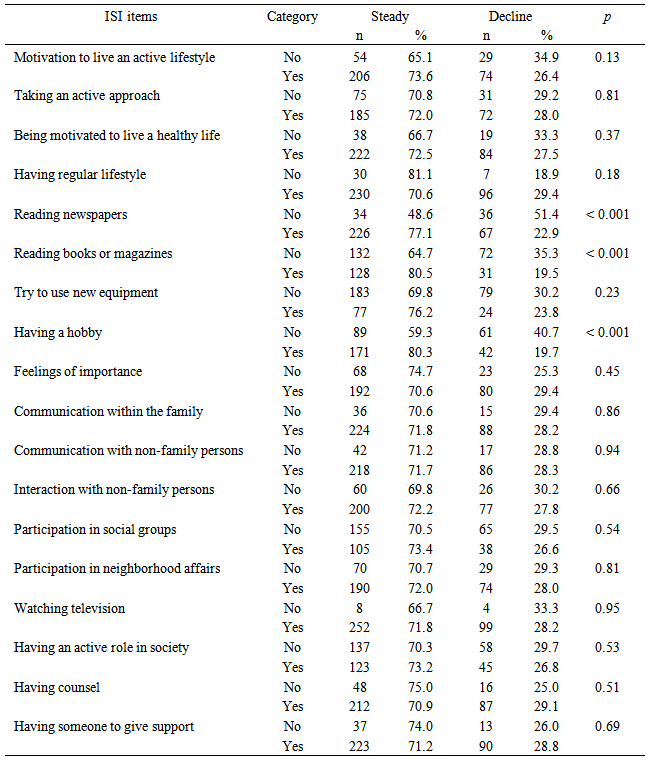

- In this study, age, gender, and continuity of social interaction were analysed as independent variables. Change in functional status was the dependent variable over this period.ISI data from 2002 and 2011 were used to evaluate continuity of social interaction. If a participant’s response was positive for an ISI item in both 2002 and 2011, it was defined as “yes, the participant had continuity on this item of social interaction.” If there was a negative response for an item of ISI in either 2002 or 2011, it was defined as “no, the participant did not have continuity on this item of social interaction.”Since each participant exhibited independent functional status in 2002, all IADL scores were eight points as measured by the Lawton-Brody IADL Scale. To examine change in functional status, participants whose 2011 IADL score was lower than in 2002 were classified as the “decline group” and those participants who maintained an eight-point IADL score in 2011were the “steady group.”The continuity of social interaction was examined. First, chi-square (X2) tests were completed to examine the relationship between continuity of ISI item and decline of functional status. Second, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to predict the functional decline from the continuity of ISI items, controlling for age and gender. All procedures were conducted using the Windows SAS 9.1 program, and P < 0.05 was accepted as the significance level for all statistical results.

3. Results

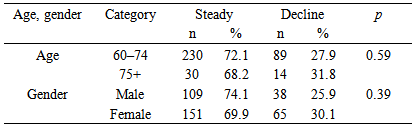

- Table 1 shows the results of analysis for age, gender, and functional status after nine years. The functional status of 89 persons (27.9%) declined in the 60–75-year-old age group and 14 persons over 75 (31.8%) exhibited functional decline. However, the proportion of functional status decline was not significantly different between these two groups. In addition, functional decline was not significantly higher among female (30.1%) versus male (25.9%) participants.

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Japan is a developed country that has been experiencing an aging population for many years. Delaying the functional decline of elders has attracted significant attention in multiple studies. Cross-sectional studies are limited in examining long-term associations, so this study focused on the association between elders’ social interactions in a baseline year and subsequent functional status with a longitudinal perspective.Although this study shows that more people tended to have declining functional status after the age of 75, this tendency was not statistically significant. Although previous studies found that elder’s functional status declined as they aged [15-17]. Other studies suggested there was no significant relationship between age and physical capacity [18]. This study emphasized that age was not a predictor for functional decline. In our follow-up surveys, some participants reported their functional status became better in comparison to previous years, so these persons’ functional status may have accounted for improvement rather than decline in functional status in this longitudinal study. This result could also suggest that there are many more important factors that affect elders’ functional status besides age.Statistical analysis did not find that gender was a factor related to elders’ functional status. Some previous studies showed similar results [16, 19], but others found a significant association between gender and functional change [15]. This discrepancy could have been caused by variance in the non-related study sample, so this study suggested more evidence is needed to clarify if gender is a predictor of functional status.After controlling for age and gender, intellectual activities within social interaction, including reading newspapers, books, or magazines, were considered significant predictors of functional decline. Many studies provide evidence that intellectual activities are associated with elders’ functional status. One previous study reported a longitudinal, independent association of positive changes in exposure to intellectual activities over a two-year period with positive changes in IADL functioning in the subsequent two years [20]. Other studies also showed that lower levels of exposure to intellectual activities were risk factors for a decline in IADL function [11, 12]. Finally, previous studies presented associations of lower intellectual activity level with overall cognitive impairment [21], and pointed out cognitive status contributed independently to the risk of functional dependence in non-disabled elders [22]. The findings of this study were consistent with previous results, and suggested long exposure to intellectual activities was more effective in protecting elders’ functional status than other social activities. In addition, the results of consistency of intellectual activities implied that engaging elders in intellectual activities should emphasize the development of the habit to maintain their cognitive ability rather than just providing chance for them.The findings of this study also indicated that having an ongoing hobby was significantly related to elders’ subsequent functional status, and this result confirmed the conclusions of previous studies. For example, some previous studies have pointed out that having less involvement in hobbies or interests was an independent predictor for depression [23], and suggested that female elders who had continued to enjoy hobbies had higher levels of cognitive function, quality of life, physical activity, social activity, and life satisfaction than those who had not [24]. Meanwhile, other existing studies have reported that there was a significant association between depression and physical decline in older adults [25, 26]. Our results suggest the association between having a hobby and depression is a key point in predicting elders’ subsequent functional status; moreover, the findings specifically indicate that continuing to enjoy a hobby could relieve the prevalence of depression and guard against functional decline in normal life. Besides, considering the cultural tradition in Japan wherein men are expected to dominate through their careers while women take charge of managing the home, the consistent hobby may be more important for male elders after retiring from their careers. In this community of study, the male elders tend to undergo a more apparent change in their social lives therefore consistent hobbies are essential to prevent them from depression when they have to face the changes in their lives.Considering the cultural tradition in Japan wherein men are expected to dominate through their careers while women take charge of managing the home, Although existing studies showed an association between participation in social activity and functional status [7, 8, 17], this study did not find a significant association with “participation in a social group.” This does not mean “participation in social group” is an ineffective factor in preventing decline, but there may be some reasons for the inconsistent results in this study. First, the details of participation were not described in previous studies. It is hard to create similar activities in different social groups, areas, and time periods. Moreover, previous studies revealed that increasing age does not reduce occupational or role engagement, and continued participation in valued roles may be important for older people’s life satisfaction [27]. Thus, the detail of “participation” (whether it includes appropriate role engagement and intellectual activity) may be decisive to the positive association. Second, nine years of ongoing social participation was probably difficult to maintain, so some individuals who had a positive result from social participation over a period of less than nine years might have been classified as lacking continuity. This may have resulted in non-significant statistical results that differed from previous studies.This study has several strengths. First, its longitudinal nature confirmed that social interaction was continual in elders’ normal lives, not just a temporary interaction at the time of survey. Second, social interaction was measured in a multi-dimensional manner. The ISI contains five subscales, which provide a rich picture of various dimensions of social interaction, and represent the dynamic nature of an elder’s daily life. Limitations within this study also existed. Since it aimed to clarify the variables affecting functional status through social interaction, other potential predictors were not evaluated. In addition, there was only one community studied, and the rate of missing responses exceeded 30 percent, potentially biasing the study.

5. Conclusions

- This study showed specific associations between the social interactions of elders living in a rural community and their functional status after nine years. It indicated that consistent social interactions that engaged elders’ cognitive abilities in intellectual activities have a positive association with delaying elders’ functional decline. In addition, having a consistent hobby was effective in protecting elders’ functional status through the relieving of depression.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We are deeply grateful to Mr. Kuno (Mayor of Tobishima), Mr. Hattori (Deputy Mayor), and all the participants and staffs of this study. This research was supported by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (21653049, 23330174).

Appendix 1. Index of Social Interaction (ISI)

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML