-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2014; 4(2): 62-70

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20140402.03

Pathways to Despair: A Study of Male Suicide (aged 25-44)

Macdonald JJ1, Smith A2, Gethin A3, Sliwka G4, Monaem A5, Powell K6

1Men’s Health Information & Resource Centre, University of Western Sydney, Richmond, NSW, 2753, Australia

2SILVERLINE Consulting, Amherst, Victoria, 3371, Australia

3Argyle Research, Hazelbrook, NSW, 2779, Australia

4United Care, Burnside, North Parramatta, NSW, 2151, Australia

5Family Planning, Ashfield, NSW, 2131, Australia

6Men’s Health Information & Resource Centre, UWS, Richmond, NSW, 2753, Australia

Correspondence to: Powell K, Men’s Health Information & Resource Centre, UWS, Richmond, NSW, 2753, Australia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Objectives This study sought to explore the real experiences in men’s lives that led them to attempt suicide. Its focus is on men, as it is men who are more likely to take their own lives. Method It was a qualitative study of two groups, involving one-to-one interviews with those who had attempted suicide and focus group discussions with those who had been close to someone who had taken their own lives. ResultsThe study showed that there was not one single factor that led to suicide but rather an interplay of difficult life experiences. Conclusion Understanding suicide and self-harm in the broader context of men’s lives is essential in order to create strategies for promoting a public health approach to suicide prevention.

Keywords: Suicide, Men, Men’s health, Social determinants of health

Cite this paper: Macdonald JJ, Smith A, Gethin A, Sliwka G, Monaem A, Powell K, Pathways to Despair: A Study of Male Suicide (aged 25-44), Public Health Research, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 62-70. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20140402.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- This study looks at the relevance of the context of male suicide through the accounts of selected men, who attempted death by suicide and members of families and friends who have lost men close to them from death by suicide. The pathways to suicide develop from a complex mix of social, economic and cultural issues, and to describe them in medical or pathological terms risks avoiding those real events in some men’s lives which can lead to suffering and despair and to the taking of their own lives. The focus of this article is on men, since in Australia, as in other countries, it is principally men who take their own lives (Coleman, Kaplan & Casey, 2011). This study adopted a social determinants of health framework, consistent with the World Health Organisation’s ecological approach to violence as a public health issue, which includes self-inflicted violence and suicide (WHO, 2004). Research within this framework is concerned with the importance of the context of people’s lives, and the impact that social, economic and emotional factors can have on health (Wilkinson & Marmot, 2006; Marmot, 2005; Macdonald, 2005; WHO, 2008), and it highlights the importance of services and players other than the health services, in the important task of attempting to prevent suicide.The Central Coast of New South Wales, Australia, was chosen for this study as it had, at the time, a higher than average incidence of male suicide, involving men aged between 25 – 44 years (Bauer, 2004). The study benefited from the participation of the Health Promotion Unit of the Central Coast Northern Sydney Area Health Service, and the Suicide Safety Network (Central Coast) Inc. (SSN), which included the Coroner’s office at Gosford, N.S.W., ensuring that accurate and specific data on local suicide was readily available to the researchers. In addition, the work was often guided by the insight and wisdom of Reverend Eric Trezise, who has worked in that area with many men at risk, and with bereaved families.This was a qualitative study involving two groups (see Table 1, for demographic information) – the first group being men who had made a serious attempt at suicide and the second group consisting of family or friends who have lost someone to suicide. The subjects were chosen from a semi-structured telephone survey where data was collected from almost 100 (mostly male) respondents from interviews using a semi-structured process. (Andrew et al, 1999). From this, eighteen interviewees were invited to participate in a one-to-one or group interview. One-to-one interviews were conducted with five men in the first group, and seven focus group interviews with the second. Such a small sample is not unique, Marshall (2005) having used just eight participants in a similar and useful study. The study set out to acquire insights into the motivations and influences of those attempting, and the perceptions of those bereaved by, suicide. There are studies dealing with the means whereby people kill themselves (and the restriction of access to these) (Ajdacic- Gross, Weiss, Ring, Hepp, Bopp, Gutzwiller & Rossier, 2008; Yip, Law, FuKing Wa, Law, Wong & Xu, 2010) but few which look at what Marmot, in the context of the social determinants framework, calls the “causes of causes” (Marmot & Wilkinson, 2006). This obliges us, if we wish to work towards prevention, to risk raising the difficult and complex issue of why people are taking their own lives. Whilst a small sample, as stated earlier, it is hoped that this study will contribute to the culture of our society by insisting that such factors be taken seriously, with a consequent effect on service provision. This study forms the basis for on-going, more quantitative and qualitative studies of the same phenomenon.

2. Interviews

- Given the sensitivity of the topic, it was important to create an atmosphere of trust and confidence and so the interviewer was experienced, well respected from the area. A relaxed atmosphere, ensuring privacy and confidentiality was created, and the process complied with the ethical requirements of the institutions involved.Table 1 below, illustrates the demographic characteristics of the participants:The four topic areas that formed the basis for discussion in the interviews were derived from work done by the Central Coast Organisations in the form of a semi-structured telephone survey (Andrews, Smith & Bauer, 1999) of approximately 100 men. Themes identified from this survey were as follows:1. The factors/issues which might have helped or hindered the respondents to be positive about their psycho-social health?• Boyhood experiences and upbringing;• School/education related experiences;• Work place issues/factors;• Relationship with partners, parents, children, friends and any other significant people;• Financial matters;• The expectations laid upon them as men in their own community.2. Their ability to manage distress – what/who helped, what did not help, and how they are coping now.3. The local services they approached in order to deal with their stress – what helped, what did not help; what do families and friends feel requires improvement in order to obtain better services from service providers; did they experience services as being male-friendly?4. Apart from providing help to individuals, what are some of the broader social and political issues which need to be addressed in order to reduce the incidence and severity of personal distress in men?

3. Analysis of Data

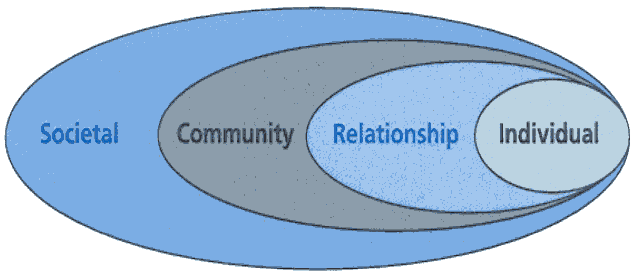

- Unraveling the stories of the participants and uncovering the pathways, and the connections between pathways, was a time-consuming and process, undertaken with as much rigour as possible, involving the three researchers reading and re-reading transcripts of interviews, singly and together. Each sentence was deconstructed for content and relevance to the study, and common themes identified. The researchers used NVivo, a qualitative text-based analysing software package (NVivo, 2004), as it assists in organising data into meaningful themes, and allows easy access to the original text for verification. The object of the analysis was to try to understand those pathways travelled by the men in question, leading them to despair and the act of suicide. The WHO Ecological Model, showing the four levels approach was taken as an explanatory framework.

| Figure 1. WHO (2004) Ecological Model |

3.1. Results from Analysis

- The main themes that emerged from the analysis were identified and listed for the two groups, and linked to the corresponding zones from the WHO model (see parenthesis below). There were other themes that emerged as contributing to the risk of suicide, such as social connections, personal characteristics, but the strongest connections were those listed as follows:Attempters§ Work related issues (Community)§ Drug/Alcohol abuse (Individual)§ Psycho-social health (Individual/Societal)§ Adverse childhood experiences (Individual § Relationship strain (Relationship)Family/Support Persons§ Drug/alcohol abuse (Individual)§ Work related issues (Community)§ Relationship strain (Relationship)§ Dissatisfaction with mental health services (Societal)Any one of these issues could be distressing in itself, but what emerges from the stories of the people involved is that when several of these are operating simultaneously, it is then that the victim treads the pathway to despair and possible self-destruction. What needs to be understood from this study is that there is no simple, single cause, but rather a “messy” interplay of contributory factors.

4. Part A: Accounts – Men who Attempted Suicide

4.1. Drugs and Alcohol

- It is clear from the accounts of this group of men that drug and alcohol abuse is one factor that has the potential to impact on all other areas of life. Strain in a relationship, for example, can prompt a respondent to have recourse to drugs and/or alcohol, to ”self-medicate”, which in turn impacts negatively on other aspects such as work, as well as worsening the relationship. Taken primarily as a means of coping with, or perhaps avoiding, a difficult situation, the escalating use of drugs/alcohol becomes a dominant feature for some men just prior to attempting suicide. Says one man speaking about difficulties in a relationship,…I was quite a different person. I don’t think I was a very enjoyable person to be with a fair bit of the time. I was very withdrawn and wasn’t very conversational, we didn’t really communicate all that much even though she probably tried to communicate with me a lot, but I probably pushed her away a lot of the time, too, when I was stoned and yeah, probably just went into my own little world a lot of the time.The term ‘depression’ gets used by people in the study, who use the term to describe feeling bad, but should not, however, necessarily be taken to mean clinical depression. What can be said, clearly, from the accounts is that substance abuse is very much linked to a desire to bury difficult feelings. …this sort of elaborated into depression and slowly but surely the alcohol didn’t come once a month, it became once a week and by the age of fourteen/fifteen I was heavily drinking.Alcohol abuse can often be exacerbated by work situations, one respondent describing doing “well’ at work, and having to take clients to lunch, which included drinking. This led him to chronic alcoholism.…and then probably bat on to dinner, so alcohol consumption was huge, business was happening, you know. There you go. Alcoholism was well and truly underway.To consider this simply in the light of, ‘He had an alcohol problem’ is to miss the context of a respondent’s life, and the inter-relationship between this and substance abuse, and subsequent attempts at suicide.

4.2. Work Related Experiences

- Work is a significant social determinant of health, and the impact of work on a person’s well-being, both mental and physical, can be found in the literature (Bottomly, Dalzeil & Neith, 2002; Wilkinson, 2006; Ferrie, Shipley, Newman, Stansfeld & Marmot, 2005). On the positive side, Marmot, Friel, Houweling & Taylor (2008) say, Work is the origin of many important determinants of health. Work can provide financial security, social status, personal development, social relations, and self-esteem and protection from physical and psychosocial hazards.On the negative though, Stress at work, defined as a combination of high psychological demands and low control or as an imbalance between effort and reward, is associated with a 50% excess risk of coronary heart disease and other indicators of mental and physical ill-health (Marmot et al, 2008).When people in this study were asked about their own experiences at work, many expressed feelings of low satisfaction, difficulty in sustaining employment, negative self-esteem resulting from the work situation, and general feelings of disaffection.I had a few of those feelings when I was putting together the plan for the grader, which faded, I guess, when I got the bad decision over the few times that we got sort of declined for the loan. I sort of slowly started to deteriorate again.Even a successful work experience, as mentioned earlier, created pressure to entertain clients, involving an increase in alcohol intake, which, when coupled with other issues in the participant’s life led to a breakdown of his relationship and a suicide attempt. For many of the participants, however, the work situation contributed to a sense of low self-esteem, which coupled with other factors, led them further down the path to suicide.

4.3. Psychosocial Health

- This term is used to reflect what is called a holistic view of the health of a person, taking into account the impact of the context of their lives over their lifespan on their wellbeing, notably, in this case, their mental wellbeing. It became apparent during the interviews that childhood experiences and experiences later in life had the potential to severely undermine the participants’ well-being. Some had been diagnosed with mental illness or depression. Generally, feelings of low esteem and sadness surfaced in many of the interviews. Sadness. Not really knowing that I was worth anything. I didn’t really feel like I was worth anything. I didn’t feel like I was going to get anywhere in life.Feeling valued and valuable is integral to sustaining good health (Macdonald, 2005), and when there is a build-up over many years of feeling negative about oneself, it is difficult to recover from this. I still have wonders about what life’s really about; probably think about whether life’s really worth it – still think about that once a day.Pollack (cited in Coleman, Kaplan & Casey, 2011) has noted that from an early age boys are taught to hide their emotions and any tendency to express emotion or vulnerability is severely censured (he calls this ‘gender straitjacketing’) and the effect was evident as these men spoke about their feelings of hopelessness and isolation. The following are three examples:The low spots were not being able to communicate, not being able to deal with feelings, not being able to ... um... not being able to ... the madness in my head, thinking I was insane, no way to stop the feelings, the projector going in my head, the suicidal thoughts... wanting to live one minute and die the next.Well, leading up to that I found myself very depressed, no one to talk to and I had all these memories and I was left alone.Everything was just hopeless, it’s really hard to describe, it was just a real feeling of desolation and hopelessness.Some participants described feelings of intense anger which have stayed with them even though their expression has changed, one man saying how as a young man he would lash out and hit things, whereas now he feels the anger building up with no way of “getting it out of your system”......so I can feel my anger getting into me – it seems to be building up I guess because things aren’t working out as much and...Sometimes what is expressed is frustration and a sense of unreality.At that time I had strange thought patterns, I couldn’t work out what was going on inside my mind. I had delusions, voices, sadness, happiness, a range of different things and I just had no idea, I had no way of coping.What pervades the narratives is a sense of sadness, of little to hope for, and no way forward and, of course, in this case, there are signs of definite mental illness, which requires appropriate care and treatment.

4.4. Adverse Childhood Experiences

- For the attempters and for those who were close to men who took their lives, the immense significance of early childhood experiences was evident from their narratives, and this is consistent with much of the research around social determinants of health. It has been found that risk factors for suicide later in life include divorce of one’s parents, substance abuse by parents, poor parent/child relationships, physical and sexual abuse, all of which undermine coping mechanisms and balance in later life (Maggi, Irwin, Siddiqi & Hertzman, 2010; Gilbert, Spatz Widom; Browne, Fergusson, Webb & Janson, 2008). Such stresses in childhood certainly affected some of the participants, one man describing the impact on the household of his father’s drinking.You know I got home that night and my mother started crying and so dad told her to ‘shut the fuck up’, and gave her a bit of a flogging and then it was my turn.Another man describes abuse at the hands of his mother and step-father, and how as a child he would pray for his mother to drink as this would at least render her unconscious for a while. Otherwise he would be dragged around the house being punched, slapped, on one occasion choked, and all the time being verbally abused, being told he was worthless. He, in turn, became an abuser.I became an abuser, I became everything, I became a woman beater, I became a person beater. I became self-harming, drug addict, everything as a result of my childhood.For another man it was not the home environment, but a stressful school situation that, whilst seemingly trivial in itself, became significant in the context of a series of negative experiences that led to despair and suicide. Self-conscious about warts on his hand, he describes his teacher’s behaviour:...we used to have once a week dancing classes and he tried to force me to dance with a girl, and I didn’t want to hold hands with the girls because of my warts, and he shouted at me and abused me in front of the class.

4.5. Relationship Strain

- Wilkinson (2005) has discussed the importance of belonging, being valued, feeling connected to a partner, and other significant family members and friends, and what emerges from the stories of men attempting suicide in this study, is the frequency of such relationships breaking down. Strong feelings of loss, anger, grief and pain, as well as overwhelming feelings of failure follow, particularly when children are involved. For one man:It was like – oh, my God, I’m not going to see my daughter again, I’m not going to be able to see my daughter.Pressure from work, where the participant was out more and more with clients, became one of the issues leading to one marriage breakdown, and contributing significantly to stress. Poor relationship with families, and having to make choices at a young age about which parent to live with, or being alienated from birth families in order to please a partner, resulting in a diminution of trust, were issues experienced by the men in this group, creating enormous strain.I was forced into going into a courtroom and sitting in front of a judge [and] saying, ‘…do you want this guy to be your father?’…and I didn’t but I was petrified but I just done what I was told.

5. Part B: Accounts from Family and Friends, who have Lost a Male Family Member or Friend from Suicide Death

5.1. Drug and Alcohol

- As in the lives of the attempters, in describing the lives of suicide victims, family members and friends observed a strong connection between drug and alcohol abuse and strain in close relationships, as well as poor mental health and low self-esteem. They describe escalating behaviour as the life gets out of control, drinking more and more as relationships break down, becoming paranoid, unable to sustain their role as a father or husband. These are comments from some of those people related to the suicide victims,Then with that, then maybe when he did split up and he wasn’t getting any sleep and he wasn’t eating right and he was smoking a lot of cigarettes and drinking a lot of beer.He was really paranoid…look I can’t do this…and saying people are watching me and I’m getting scared now, and I think that might have been the speed in his system at that time.I think his attempt to be a husband and father was very real, but we had the problem of alcoholism rearing its ugly head all the time and he didn’t realise how much that affected his whole physical, mental, social, spiritual life.

5.2. Work Related Issues

- Family and friends saw negative work experiences as a significant factor in the lives of some of the victims, who either lost their jobs or were frustrated at work. A sister describes her brother’s dissatisfaction with work and then how his self-esteem plummeted when, in desperation, he took a job which paid $2.00 per hour.But his self-esteem just went out the window then, that’s why I think he had a big episode breakdown, because like my self-esteem would go down too for $2.00 an hour.Unemployment is an indicator of a lack of social cohesion in society, which can lead to suicide (Marmot, 1999; Kposowa, 2001); Spikblad-Lundin, 2011). Apart from feelings of low-esteem, a sense of isolation and of not being part of the working community can increase the vulnerability of the victim. Says one wife, whose husband had committed suicide six years previously, He only got mediocre jobs that didn’t earn the same money [as previously] and that was very frustrating to him and he got very depressed – he got quite depressed about that.

5.3. Relationship Strain

- Strain in relationships figures significantly in the accounts of family and friends of victims of suicide, as they describe how it impacted on their self-esteem, creating feelings of worthlessness. One partner recounts how finding work before her partner did, built up feelings of resentment in herself, thus impacting on the relationship.…because I was still in the workforce and I had to be there, so after ten months of maternity leave I was forced to get back to work. We just couldn’t survive. So I could feel this resentment building up in me…Some of the people in this group saw incompatibility between partners as an issue, and here are some of their comments,I can see it now. I can. I still thought we were playing happy families right up until his death.…and met a girl and eventually had his child, but he was never allowed to see and that was aggressive and didn’t help him…

5.4. Dissatisfaction with Services

- In the narratives of those who had lost a close relative to suicide, what emerged is a sense of frustration as they tried to get assistance from local services. This applied whether it was mental health services, welfare or legal agencies. The main issues were, a) fragmentation of services;b) inexperience of mental health workers and the need for mentoring; c) the perceived differences between Drug and Alcohol Services and Mental Health Services – some felt that Drug and Alcohol services are more accustomed to males, while Mental Health Services had a stereotypical view, and did not get the ‘male point of view’.A sister who tried to get help for her brother before his death describes inadequate consultation by psychiatric staff, lack of co-ordination among service providers for treatment, the patient’s records were lost, all of which contributed to the victim’s stress when he urgently needed support. For another family, the services of the mental health agency were inadequate, and the psychiatric nurse assigned to the patient was seen to have failed in her duty of care as she did not take his threats of suicide seriously. Another member of the family complained about the poor exchange of information between agencies. When her husband went missing, she was unable to trace him, and he subsequently committed suicide.When he went missing, I couldn’t find out his whereabouts, and he was drawing the dole up in Queensland, and with the freedom of information, the police weren’t allowed to find out from the Department of Social Security about these…She felt that, had the information been passed on between the agencies, her husband may have been found sooner and given the help he needed.In some cases the assistance offered was from people lacking experience in dealing with potential suicide victims, and they were unable to provide the much needed support. These comments from some of those who felt the inadequacy of the support,…you get different youth workers and you can tell who’s a textbook worker and who’s a real life worker…The hospitals, they just don’t believe people. They don’t take them all…I feel they should take them all seriously. If somebody threatens suicide then take it seriously, but they’re not. It’s…once again…it’s probably a money situation…we haven’t got hospital beds, we haven’t got this, we haven’t got that…but it’s…and if the government thinks there’s not enough, how many is enough? With one suicide, there’s the mother, the father, the sisters, the brothers, the aunts, the uncles, the best friends and they’re all suffering for one suicide. One’s too many.One family described their anguish as they dealt with police, who they felt were biased against their son. Because he had been charged with assault, they judged him and discriminated against him.This study attempts in a modest way to give voice to the people involved, and this is important. However, listening to those involved in service provision would also reveal frustration and difficulties, lack of resources being the most significant.

6. Resilience

- Given the study’s preoccupation with prevention, interest focused on discovering those factors which were potentially buffering or supportive in giving participants the strength to go on with life. The notion of resilience comes closest to what was being sought, many researchers acknowledging the importance of social support for positive mental health and in building resilience. This has been defined as the capacity for successful adaptation to change, a measure of stress coping ability or emotional stamina, the character of hardiness and invulnerability, or the ability to thrive in the face of adversity or recover from negative events (Conner, 2006; Olsson, Bond, Burns, Vella-Brodrick& Sawyer, 2003). This is clearly related to Antonovosky’s ideas about salutogenesis – the capacity to come through even the most harrowing situations (Antonovsky 1979, 1987; Macdonald, 2005). Resilience is seen as a protective factor against the development of psychiatric disorder in the face of adversity (Rutter, 1993; Seery, Holman & Cohen, 2010), and Roy, Sarchiapone, &Carli (2007) found it strange that resilience had not been examined directly in relation to suicidal behaviour. It has been noted by some researchers that those who are regularly surrounded by close, supportive and comforting individuals show reduced neurocognitive and physiological stress responses in certain situations, and over time this may well result in better health outcomes. Understanding this link between social relations and health may be crucial in improving health outcomes, and reaffirms the importance of social relationships for survival (Eisenberger, Taylor, Gable, Hilmert & Lieberman, 2007) and also clearly reinforces the evidence showing that social support is a major determinant of health (Wilkinson & Marmot, 2005).The literature also discusses ‘hardiness’, and this is clearly related to resilience:It helps to buffer exposure to extreme stress. Hardiness consists of three dimensions: being committed to finding meaningful purpose in life, the belief that one can influence one’s surroundings and the outcome of events, and the belief that one can learn and grow from both positive and negative life experiences. Armed with this set of beliefs, hardy individuals have been found to appraise potentially stressful situations as less threatening, thus minimizing the experience of distress. Hardy individuals are also more confident and better able to use active coping and social support, thus helping them deal with the distress they do experience (Bonnano, 2004).A study such as this one, as has been said, is primarily interested in suicide prevention, so it was considered important to look for the absence or presence of resilience or hardiness in the lives of those attempting suicide. Taken from the previous list of themes, it was felt that those that could be related to resilience were, • Social connections within family• Social connections with religion• Social connections outside family• Feeling valuedIn looking at the comments from those who attempted suicide, it must be noted that they are made after the attempt(s) at suicide and are what they see as factors helping them survive and turn away from suicide (often by means of some form of what we can call ‘social support’).

7. Family

- From a ‘post attempt’ perspective, one participant comments, “I can’t do this by myself”, and then identifies what has helped him to get through. Despite childhood trauma, he comments positively on his parent’s efforts since his suicide,I wouldn’t be the man I am today if it wasn’t for a lot of their good attributes.Many derived support and comfort from their birth families. Even after breaking contact in one case, because the man’s partner had issues with his family, they came to his aid when he attempted suicide.And…um, my brother and I had been talking by this stage for about three or four months and we get along all right now, and he and his wife turned up on the day of the court with their baby boy who absolutely adores me and they stayed with me the whole day, eventually eight or nine hours.

8. Church and Other Social Groups

- Spirituality, and having a religious affiliation (acknowledged as not necessarily being the same thing) have been shown to have sometimes, at the least, a buffering effect in the lives of people suffering distress, providing them with a coping strategy (Dein, Cook, Powell & Eagger, 2010). Whilst there are exceptions, where religious practice can denote pathology, there is significant evidence to support the notion of this positive correlation between religious involvement and good mental health (Levin, 2010).I mean being part of…my being part of the church, being my faith in God, again in the 12 steps program, being part of…not being unique…knowing that there’s other people out there like me and having that support network is very important, whether it be AA, NA or GA.Religion can also give the person a sense of being valued, of self-worth (see the section below on being valued).What some researchers say about sense of belonging and community and health in Canada, surely applies elsewhere:The strength of the association between community- belonging and health-behaviour change in general suggests that community-belonging could be an important component of primary prevention initiatives aimed at increasing health through broad population initiatives. Community-belonging may represent greater social integration within one's community, increased access to social support, aswell as material, cultural and psychosocial resources for improving one's health (Hystad & Carpriano, 2012).In this vein, other participants mentioned the supportive element in the group dimension of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). When this sort of support is not available and the person feels as though he is not understood, then there is a negative effect on his coping mechanism.

9. Individual Support

- For one man connection with a supportive person was important, one who had been in a similar position of despair…I just had said it’s all too hard, mate, I don’t want to be around anymore and he picked up on that, ‘cause I think he’d been there himself. And he said, ‘You’re in a very dark space’ and came around and picked me up… yeah … and I told him what I’d done.The love and support of a friend or partner can be a lifeline, and an unexpected visit from a friend from his earlier life gave hope to one man in hospital after an attempt at suicide.I had a school friend come and visit me a few times and I thought, people do care.They went on to form a positive relationship.One man had no such support, and in desperation he created a person who became so real, he called him Peter.…I was actually crying out for Peter, and at that stage Peter was a friend and Peter was inside my head. I was calling out for this Peter and then searching high and low for this Peter, and I knew all along that there was no Peter, but I thought there was.

10. Feeling Valued

- Negative beliefs about oneself which have been ingrained from childhood reinforce what the social determinants of health literature says about the importance of early life in determining people’s physical and mental health and their resilience in later life.Slow growth and a lack of emotional support during this period (early life) raise the life-time risk of poor physical health and reduced physical, cognitive and emotional functioning in adulthood (WHO, 2003).Not feeling valued reduces our capacity to cope with difficult issues, our resilience. One participant describes how he has moved from feelings of despair which led him to attempt suicide.It’s starting to get by where I’m starting to cope with these fears and these inadequates [sic] that I have in my mind, these beliefs that were ingrained at such young age that I was such a bad kid or such a bad person. It’s only now come out that I can look at them and realise and say, Oh, well, God doesn’t make mistakes and God will be there for me at the end.

11. Conclusions

- This study has shown that the pathways to suicide do not involve one single factor, but are often characterised by the experience of an accumulation of difficult life situations. The interviews with those who had attempted suicide and the interviews with family and friends are remarkably similar in some of their themes, not least of which is the underlying theme of the importance of being valued in one’s life. Neglect, abuse and lack of support in childhood were frequently present in the narratives of those men who had attempted suicide, supporting other literature that recognises the impact of these things on people later in life. What is significant is that the cumulative effect of these factors impact negatively on resilience, often leading to drug and alcohol abuse as a way of coping, which in turn has a deleterious impact on relationships, and other areas of life. In both sets of interviews work was a prominent issue in the narratives, stress and problems at work profoundly affecting some of the participants. Unemployment also figured as an important determinant of health, with feelings of failure and low self-esteem resulting from the inability to sustain employment. Loss of a relationship, or conflict within a relationship also led men to despair, especially when this involved being separated from children.When one of these factors is experienced in isolation it rarely leads to suicide, but when several are present in a person’s life the cumulative effect can be, and has been, disastrous. This study also noted that those who attempted suicide, or the family and friends who lost someone through suicide, experienced difficulty negotiating available services for help. Several expressed the opinion that mental health and legal services had failed to give appropriate support to men when it mattered, and seemed to lack efficient referral systems that could have provided a full range of support for potential suicide victims. When this is coupled with the fact that men canfind it difficult to seek appropriate counselling in the first place, the result is yet another step along the pathway to despair.It is perhaps to say the obvious that for many men on the pathway to despair an important factor is the sense of not being valued, and that any attempts to support people on a trajectory to suicide must take this into account. In addition, what we can say with some certainty is that understanding suicide and self-harm in the broader context of men’s lives is essential in order to create long-term strategies for promoting a public health approach to suicide prevention.

References

| [1] | Ajdacic-Gross,V., Weiss, M.G., Ring, M., et al. (2008). “Methods of suicide: international suicide patterns derived from the WHO mortality database”. (Research)(Report) Pub: Bulletin of World Health Organization.pp.726(7). |

| [2] | Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, Stress, and Coping.San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. |

| [3] | Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unravelling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. |

| [4] | Andrew, L., Smith, A. & Bauer, L. (1999). “Men – it’s your call”, Health Promotion Unit, Central Coast Health, Ourimbah, NSW. Retrieved June 2011 from: http://www.suicidesafetynetwork.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Men-Its-Your-Call.pdf. |

| [5] | Bauer, L. (2004). “Suicide on the Central Coast: 2003 Health Report”, Health Promotion Unit, Central Coast Health. Available from:http://www.suicidesafetynetwork.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Suicide-on-the-Central-Coast-Report-2003.pdf. |

| [6] | Bonnano, G.A. (2004). “Loss, Trauma, and Human Resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events?” American Psychologist. 59(1), pp. 20-28. |

| [7] | Bottomly, J., Dalziel, E. &Neith, M. (2002). “Work Factors in Suicide”. Creative Ministries Network. East Victoria. Available from:www.cmn.unitingcare.org.au/pdf/WorkFactorsin Suicide.pdf. |

| [8] | Brodsky, B.S., Oquendo, M., Ellis, S.P., et al.(2001). “The relationship of childhood abuse to impulsivity and suicidal behaviour in adults with major depression”. American Journal of Psychiatry. 158, pp. 1871-1877. Available from, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11691694. |

| [9] | Coleman, D., Kaplan, M.S. & Casey, J.T. (2011). “The Social Nature of Male Suicide: A New Analytical Model”. International Journal of Men’s Health. 10 (3), pp. 240-252. |

| [10] | Conner, K. (2006). “Assessment of resilience in the aftermath of trauma”. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67(2), pp. 46 – 49. |

| [11] | Daigle, M. (2005). “Suicide prevention through means restriction: Assessing therisk of substitution: A critical review and synthesis”. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 37, pp. 625-632. |

| [12] | Dein, S., Cook, C.C.H., Powell, A. &Eagger, S. (2010). “Religion, spirituality and mental health”.The Psychiatrist34, pp. 63-64 doi:10.1192/pb.bp.109.025924†http://pb.rcpsych.org/content/34/2/63.full. |

| [13] | Eisenberger, N.I., Taylor, S.E., Gable, S.L., et al. (2007). “Neural pathways link social support to attenuated neuroendocrine stress responses”. NeuroImage.35(4), pp. 1601-1612. |

| [14] | Fergusson, D.M., Woodward, L.J. &Horwood, L.J. (2000). “Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behaviour during adolescence and early adulthood”. Psychological Medicine. I, pp. 23-29. |

| [15] | Ferrie, J., Shipley, M., Newman, K.et al. (2005). “Self-reported job insecurity and health in the Whitehall II Study: potential explanations of the relationship”. Social Science and Medicine. 60, pp. 1593 – 1602. |

| [16] | Hystad, P. &Carpiano, H. (2012). “Sense of community- belonging and health-behaviour change in Canada”. Research Report. Journal of Epidemiology Community Health.66, pp. 277-283doi:10.1136/jech.2009.103556. |

| [17] | Kposowa, A.J. (2001). “Unemployment and suicide: a cohort analysis of social factors predicting suicide in the US National Longitudinal Mortality Study”. Psychological Medicine.31, pp. 127-138. |

| [18] | Levin, J. (2010). Religion and Mental Health: Theory and Research. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies.7(2), pp.102–115 DOI: 10.1002/aps.240. |

| [19] | Macdonald, J. (2005). Environments for Health. London: Earthscan. |

| [20] | Marmot, M. (1999). “Job insecurity in a broader social and health context”.WHO Regional Publications. European Series. 81, pp. 1-9. |

| [21] | Marmot, M. (2005). “Social Determinants of Health inequalities”.The Lancet. 365, pp. 1099-1104. |

| [22] | Marmot, M. & Wilkinson, R.G. (Ed) (2006). Social Determinants of Health. Oxford University Press: Oxford. |

| [23] | Marmot, M., Friel, S., Houweling, T. et al. (On Behalf of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health). (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet. 372(9650), pp. 1661-1669. |

| [24] | Marshall, D.S. & Schultz, D. (2005). Service provision in response to suicide: A qualitative investigation. Georgia State University. 3166982. |

| [25] | Olsson, C.A., Bond, L., Burns, J.M., et al. (2003). “Adolescent resilience: a concept analysis”. Journal of Adolescence. 26, pp. 1-11. |

| [26] | Roy, A., Sarchiapone, M. &Carli, V. (2007). “Low Resilience in Suicide Attempters”. Archives of Suicide Research. 11(3), pp. 265-269. |

| [27] | Rutter, M. (1993). “Resilience: Some conceptual considerations”. Journal of Adolescent Health. 14, pp. 626-631. |

| [28] | Seery, M.D., Holman, E.A. & Cohen-Silver, R. (2010). “Whatever does not kill us: Cumulative Lifetime Adversity, Vulnerability, and Resilience”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.99(6), pp.1025–10410022-3514/10/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0021344. |

| [29] | Spikblad-Lundin, A. (2011). Unemployment and Mortality and Morbidity – Epidemiological Studies.Thesis published by the Karolinska Institute. |

| [30] | Theorell, T. Siegrist, J. & Marmot, M. (2006). “Health and the psychosocial environment at work”.In Marmot, M. & Wilkinson (Eds). Social Determinants of Health (pp.97 – 124). Oxford: University Press. |

| [31] | Wilkinson, R.G. (2005). The impact of inequality: how to make sick societies healthier. New York: The New Press. |

| [32] | Wilkinson, Richard G. (2006) “Health, hierarchy, and social anxiety." Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896(1): pp.48-63. |

| [33] | Wilkinson, R.G., & Marmot, M. (2006) (Eds). Social Determinants of Health. Oxford University Press. World Health Organisation (WHO) (2003).The Solid Facts.Geneva: WHO. |

| [34] | World Health Organisation (WHO)(2004). Preventing Violence: a guide to implementing the recommendations of the world report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO. Available from:http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/9241592079.pdf. |

| [35] | World Health Organisation (WHO) (2008). Commission on Social Determinants of Health – Final Report. Available from:http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/index.html. |

| [36] | Yip, P.S. F.; Law, C.K.; Fu, King-Wa; et al. (2010), “Restricting the means of suicide by charcoal burning”. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 196(3), March 2010, p 241–242. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML