-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2014; 4(2): 45-50

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20140402.01

Treatment Outcomes of Private-Private Mix Tuberculosis Control Program in South-Eastern Nigeria

Prosper O. U. Adogu1, Henry A. Efegbere1, 2, Arthur E. Anyabolu3, Emeka H.Enemuo3, Anthony O. Igwegbe4, C. I. A. Oyeka5

1Department of Community Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, P.M.B. 5025, Nnewi, Anambra State, Nigeria

2Department of Research and Training, Global Community Health Foundation, P.O. Box 2887, Nnewi, Anambra State, Nigeria

3Department of Internal Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, P.M.B. 5025, Nnewi, Anambra State, Nigeria

4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, P.M.B. 5025, Nnewi, Anambra State, Nigeria

5Department of Statistics, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Prosper O. U. Adogu, Department of Community Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, P.M.B. 5025, Nnewi, Anambra State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

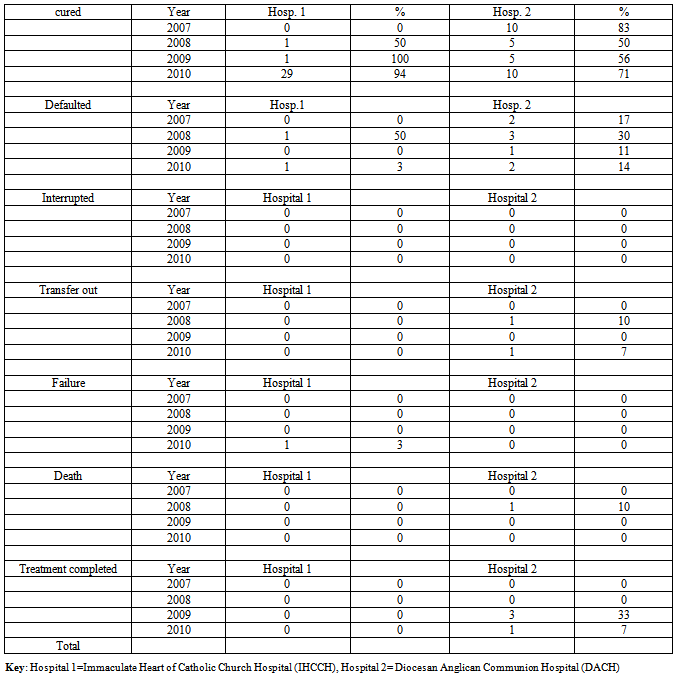

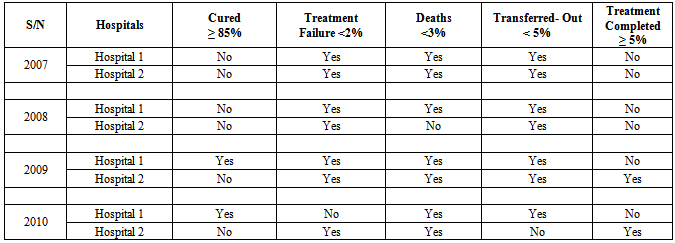

The aim of this study was to assess treatment outcomes of private-private mix Tuberculosis (TB) control program in South-Eastern Nigeria. A retrospective cohort study design was used to analyze secondary data set (2007-2010) of patients accessing TB Directly Observed Short course treatment in two private health facilities Hospitals 1 and 2 in South-Eastern Nigeria. Gender of patients were male: female 48% (34 patients): 52% (37 patients) and 60% (29 patients): 40%(19 patients) in Hospitals 1 and 2 respectively. Treatment outcomes were compared against targets set by WHO which are 85% cure rate, 5% treatment completed, 1-2% treatment failure, 2-3% deaths, 5% lost, and 5% transfer out. Gender of patients were male: female 48%(34 patients): 52% (37 patients) and 60%(29 patients): 40% (19 patients) in Hospitals 1 and 2 respectively .In 2007 health facilities adjudged as effective were, Hospitals 1and 2 using the indicator of treatment failure rate; Hospitals 1 and 2 using the indicator of death rate; Hospitals 1 and 2 using the indicator of transfer out rate. In 2008: Hospitals 1 and 2 using the indicator of failure rate; Hospital 1using the indicator of death rate; Hospitals 1 and 2 using the indicator of transfer out rate. In 2009, effective health facilities was only Hospital 1 using the indicator of cure rate; Hospitals 1 and 2 using the indicator of treatment failure rate ; Hospitals 1 and 2 using the indicator of death rate; Hospitals 1 and 2 using the indicator of transfer out rate; Hospital 2 using the indicator of Treatment completion rate. In 2010: only Hospital 1 using the indicator of cure rate; Hospitals 1 and 2 using the indicator of treatment failure rate; Hospitals 1 and 2 using the indicator of death rate; only Hospital 1 using the indicator of transfer out rate; Hospital 2 using the indicator of treatment completion rate. In conclusion, Hospital 1 was more effective than Hospital 2 facility over the four years time period.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Effectiveness, Treatment Outcomes, Private-Private Mix

Cite this paper: Prosper O. U. Adogu, Henry A. Efegbere, Arthur E. Anyabolu, Emeka H.Enemuo, Anthony O. Igwegbe, C. I. A. Oyeka, Treatment Outcomes of Private-Private Mix Tuberculosis Control Program in South-Eastern Nigeria, Public Health Research, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 45-50. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20140402.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- World Health Organization (WHO) developed the use of directly observed treatment short course (DOTS) strategy to effectively control tuberculosis (TB) pandemic [1]. The global target for TB control through full DOTS expansion was the attainment of 70% case detection and attainment of 85% cure rate by 2005 [2]. Though critical, these targets are insufficient in achieving the TB- related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) target of halting the spread and beginning to reverse the incidence of TB by 2015 [3]. Unfortunately, even these targets were not achieved, especially in Africa by the year 2005 [4]. One major constraint identified as limiting the attainment of these targets is the non-involvement of the private sector in the TB control programs [5], hence, to improve DOTS implementation WHO has begun addressing the issue of private providers in TB control. Some experts believe that private health facilities not only out number public health care providers in some countries but also manage a large proportion of the unreported TB cases [6]. Private health facilities also often offer better geographical access and more personalized care than the public facilities [6]. This resulted in the formation of a global TB control strategy called public-private mix for DOTS implementation (PPM DOTS) as promoted in the current Stop TB strategy [7,8]. However, much still remains to be accomplished if the epidemic is to be controlled in the face of dwindling resources [9,10]. Recommendations on how to evaluate treatment outcomes using standard categories have been issued by the WHO in conjunction with the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease [11]. In a study at the Makati Medical Center DOTS Clinic, a private health facility in Philippines, treatment success attained was 79.5% (108 patients), 10% (14 patients) had treatment failure; 5% (7 patients) were lost, 4.5% (6 patients) died and 1% (1 patient) transferred-out [12]. In Nigeria the treatment success rate of smear positive TB cases increased from 73% in 2004 to 82% in 2008 and 83 % in 2009 [13]. In a study conducted in Kaduna State, northern Nigeria the cure rate was 60.9% among patients managed by the private health facilities. The defaulter rate was 5.8% among patients managed by the private facilities. Treatment success (that is, the combination of cure rate and treatment completion) was 83.7 % among patients managed by the private facilities [14]. In another study in a private hospital in Imo state of south-eastern Nigeria the outcomes obtained were 56% cure rate, 14.4% defaulted, 11.1% died, and 1.7% treatment failure [15]. Treatment outcomes are compared to the targets for new smear-positive pulmonary TB (PTB) set by the WHO which are 85% cure rate, 5% treatment completed, 1-2% treatment failure, 2-3% deaths, 5% lost, and 5% transfer out [16]. For Private Public/Private Mix (PPM) DOTS to be effective it may be necessary to assess how much effective are the private health facilities on the DOTS strategy. The objective of this study was, therefore, to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment outcomes of private-private mix form of PPM in the management of tuberculosis patients by private health facilities in Nnewi North Local Government Area in Anambra State, Nigeria.

2. Materials and Methods

- Nnewi, a major commercial city in south-eastern Nigeria, has an area dimension of 72 km2 and an approximate population of 155,443 (77,517 males and 77,926 females) with average population density of 2,159 people per km2 [17]. Igbo language is the vernacular though English is widely spoken. There are about 64 registered hospitals at Nnewi, 2 missionary hospitals, 1 tertiary (Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital) and 24 primary health centers [18]. The sampling technique used to select two private health facilities (Immaculate Heart of Catholic Church Hospital (Hospital 1) and Diocese of Anglican Communion Hospital (Hospital 2)) was a multi-stage sampling technique. Stage I: Selection of Nnewi North Local Government Area (L.G.A.) by purposive sampling technique from a sampling frame of 21 L.G.As in Anambra State. Stage II: Selection by systematic random sampling technique of two private health facilities that have been providing DOTS services for the past six years and registered with Anambra State Government Ministry of Health. The study population were tuberculosis patients that accessed DOTS anti-tuberculosis care in Nnewi North Local Government Area (LGA) at Hospitals 1 and 2 from the period of 2007 to 2010 (a four year period). Only health facilities registered with the Anambra State Government Ministry of Health and have been providing Directly Observed Therapy Short course (DOTS) services for treating TB for the past six years were enlisted for the study. Also, patient treatment cards with information on any of the six treatment outcomes according to the WHO [19] and treatment completion rate outcome according to other researchers [20], socio-demographics (that is, age and sex), HIV status, year of treatment initiation and category of DOTS administered were evaluated. Treatment outcomes definitions, adapted from an international standard classification, were as follows: (1) cured (a smear-positive patient based on the medical record, who had a negative sputum smear during the eighth month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion); (2) died (a patient who died during treatment irrespective of cause); (3) failed (a smear-positive patient who remained smear-positive at the fifth month of treatment); (4) defaulted (a patient who did not come back to complete chemotherapy and there was no evidence of cure through the sputum result during the fifth month of therapy), (5) treatment interruption (a patient who did not collect medications for 2 months or more at a particular time or at interval, but still come back for treatment and in the 8th month of treatment, the sputum result was positive), and (6) transferred out (a patient who was transferred to another treatment center and for whom treatment results are not known) [19]. Another terminology hereby analyzed, treatment completion rate is the percentage of patients who completed treatment but without laboratory proof of cure, of new smear positive patients [20]. A retrospective cohort study design was used to evaluate the treatment cards of TB patients accessing DOTS anti-tuberculosis for treatment outcome for the period of 2007-2010. Data set of the selected treatment cards that have information of inclusion criteria were extracted using a checklist. Data was analyzed using computer software package SPSS version 17. Results of variables were represented in tables. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Nnamdi Azikiwe University/ Teaching Hospital Ethical Committee (NAU/NAUTHEC). Permission to conduct this study was obtained from heads of the two DOTS Centers in Nnewi North Local Government Area, south-eastern Nigeria.

3. Results

- Gender of patients were male: female 48% (34 patients): 52% (37 patients) and 60%(29 patients): 40%(19 patients) in Hospitals 1 and 2 respectively (see Table 1).

|

|

4. Discussion

- Tuberculosis control is one of the many public health challenges for which innovative approaches to public-private partnership are being sought, partly because the private health sector is often the first point of contact for many patients with tuberculosis [5]. Although the present study showed that the proportion of patients load managed at the two private comparable health facilities were 53% and 47% (averagely same level!) for Hospital 1 and 2 respectively, studies elsewhere indicate that private health facilities manage reasonably high number of tuberculosis cases [21]. The later study in India noted that 60% of individuals with a longstanding cough first went to a private practitioner [21]. Indeed, evidence shows that in many developing countries much of the populations across all socio-economic strata are known to turn to individual or institutional private health care providers [22]. Preference of some tuberculosis patients to private health facilities may be because they are often located close to and are often trusted by the community [5]. Since a reasonable number of tuberculosis patients are first treated by private health facilities World Health Organization is scrutinizing the effectiveness of treatment of these cases by the private practitioners with the aim of improving tuberculosis management, hence, the establishment of the private-private mix as a component of the public-private mix. Indeed, all of the published studies from Asia and many other parts of the developing countries have identified important shortcomings in effectiveness of tuberculosis cases management by the private practitioners [23-25]. This study also showed that majority of patients in cohort in the two private facilities was male which is in keeping with studies elsewhere [26-28]. This implies emphasis should be placed on shifting PPM DOTS from facility care to Community TB Care [29] with more advocacy to the male more than the female dominated community-based organizations. This will enhance TB care program sustainability in a male dominated culture in south-eastern Nigeria in the long run. In this study the cure rate trends at both private health facilities were increasing (2008-2010) with cure rate in Hospital 1 in 2009 and 2010 meeting the WHO target of 85%, unlike the cure rate of 80%, 56% and 61% reported in Barangay San Lorenzo, Philippines [12], Imo State, south-eastern Nigeria [15] and Kaduna State, northern Nigeria [14] respectively which were ineffective by not meeting the WHO target. This is a testimonial to the need for promoting private-private mix model of the public-private collaboration strategy in developing economies. Death rate trends at both facilities were decreasing except in 2008 with 10 % record in Hospital 2.The later value is almost same with that obtained in a study in northern Nigeria [14] but higher to that reported in a study at Philippines [12]. Failure rate trends at both facilities were decreasing except in 2010 when it was 3% in Hospital 1 which is less than that reported by Quelapio et al [12] but higher than that reported by Enwura et al [15] in Imo State of south-eastern Nigeria. This could be an indication of better standardization of DOTS practices by private-private mix in Nigeria than what obtains in the Philippines. Transfer out rate trends at both facilities were decreasing showing a possible capacity to satisfy patients’ health seeking behaviour. This is in keeping with findings of Bennett [22] and Okeke & Aguwa [5] that preference of some tuberculosis patients to private health facilities may be because they are often located close to and are often trusted by the community. Defaulter rate trends were decreasing at both facilities (2008-2010), though with ranges of 50% to 3% and 30% to 11% in Hospitals 1 and 2 respectively. In a study by Okeke & Aguwa [5] in south-eastern Nigeria, private facilities were found to have constraints; while about half of the private facilities have heard about DOTS strategy and keep record of their patients, only a few follow up their patients after treatment and have facilities for tracing defaulters. These findings are similar to those of many other researchers [21]. In a study by Kumar (2001) about 20% of private practitioners maintain a record of tuberculosis patients under their treatment while none of them had facility to trace a defaulting patient receiving tuberculosis treatment [30]. The high level of defaulter rate among private facilities in south-eastern Nigeria is most likely to be due to the fact that many of them do not place much importance to contact tracing in TB management.The limitations of this study are that private DOTS services providers used in Anambra State were all faith-based, non-profit health facilities and so there was no opportunity to compare the TB programming and TB treatment outcomes of the Faith-based organization with those of private for-profit organizations. Also, the accuracy of secondary data collected from patient’s record card for the study depended on the accuracy and completeness of the record cards as filled in by the health workers in the facilities.

5. Conclusions

- Hospital 1 was more effective than Hospital 2 facility over the four years. Thus, involving private health facilities in management of tuberculosis is vital to achieving tuberculosis control since records show that they manage a good number of tuberculosis patients. It is important that the private facilities practitioners undergo continued medical education on National Tuberculosis Control Programme and their practice should be monitored and supervised by the National TB Control Program. Moreover, the government should finance private- private mix operations including drug cost and cost for staff supervision, monitoring and evaluation activities. Further research is needed to assess effectiveness of treatment outcomes in faith-based organizations versus profit-based organizations private health facilities to identify determinants of treatment outcomes in private-private mix and deploy technical efficiency assessment using non-parametric statistics to assess the validity of assessing effectiveness using only the WHO standards.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors greatly appreciate the assistance of trained research assistants that collated data for this study and cooperation of the private health facilities in the study area.

References

| [1] | World Health Organization, 1994, Framework for Effective Tuberculosis Control. WHO/TB/94.179. Geneva. |

| [2] | World Health Organization, 2006, Stop TB Partnership DOTS Expansion Working Group, Strategic Plan 2006-2015; WHO/HTM/2006.370. |

| [3] | World Health Organization, 2007, Global tuberculosis Control, Surveillance, Planning and Financing (121-123), STOP TB department WHO, Geneva. |

| [4] | African Union Update on Tuberculosis Control in Africa, 2006, Special Summit of the African Union on HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (ATM) Sp/Ex.CL/ATM/4 (1) Abuja. |

| [5] | Okeke, T.A., and Aguwa, E.N., 2006, Evaluation of the Implementation of Directly Observed Treatment Short course by Private Medical Practitioners., Tanzania Research Bulletin 8(2), 86-88. |

| [6] | Lonnroth, K., Uplekar. M., Arora, V.K., Juvekar, S., Lan, N.T.N., Mwaniki, D. and Pathania, V., 2004, Public-private mix for DOTS implementation: what makes it work? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 82, 1-13. |

| [7] | Federal Ministry of Health, 2004, Health Sector Reform Program., Abuja. |

| [8] | Uplekar, M., 2003, Involving private health care providers in delivering of TB care: growing strategy. Tuberculosis 83, 156-64. |

| [9] | Maher, D., Hausler, H.P., and Raviglione, M.C. ,1997, TB Care in Community organizations in Sub-Saharan Africa; practice and potential., Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 1(3), 276-283. |

| [10] | World Health Organization ,2003, Treatment of tuberculosis guidelines for national programs (3rd ed.). Geneva [Online] Available: http ://www.who.int .(Accessed July 20, 2013). |

| [11] | Quing-Song, B., Yu-Hua, D., and Ci-Yong, L., 2007, Treatment outcomes of new pulmonary tuberculosis in Guangzhou, China 1993-2002 based cohort study , BMC Public Health 7 , 344. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-344. |

| [12] | Quelapio, I.D., Mira, N.R., Abeleda M.R., Rivera, A.B., and Tupasi T.E., 2000, Directly Observed Therapy–Short Course (DOTS) at the Makati Medical Centre., Phil J Microbiol Infect Dis 29(2), 80-86. |

| [13] | Federal Ministry of Health, 2010, National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Program of Nigeria: 2009 Annual Report., Abuja, Nigeria. |

| [14] | Gidado, M., and Ejembi, C.L., 2009, Tuberculosis Case Management and Treatment Outcome: Assessment of the Effectiveness of Public-Private Mix of Tuberculosis Program in Kaduna State, Nigeria., Annals of African Medicine 8(1), 25-31. |

| [15] | Enwura, C.P, Emeh, M.S., Izuehie, I.S., Enwuru, C.A., Umeh, S.I., and Agbasi, U.M., 2009, Bronco-pulmonary tuberculosis Laboratory diagnosis and DOTS Strategy outcome in a rural community. African Journal of clinical and experimental microbiology. |

| [16] | World Health Organization, 1996, Managing tuberculosis at the RHU level: Quarterly reporting on treatment result., TB Control Service, Department of Health. |

| [17] | Federal Government of Nigeria, 2006, National Population Commission., Abuja |

| [18] | Anambra State Government of Nigeria, 2013, Ministry of Health Awka. |

| [19] | International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 1996, Tuberculosis guide for low income countries (4th ed.), Paris. |

| [20] | Maimela, E., 2009, Evaluation of Tuberculosis treatment outcomes and the determinants of treatment failures in the Eastern Cape Province (2003-2005)., MSc thesis, University of Pretoria, South Africa. |

| [21] | Uplekar, M., Pathania, V. and Raviglione, M. , 2001, Private practitioners and public health: weak links in tuberculosis control. Lancet 358, 912-916. |

| [22] | Benneth, S. ,199, The mystique of markets: public and private health care in developing countries., Public Health and Policy Departmental Publications. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine 4, 1-24. |

| [23] | Uplekar, M.W. and Shepherd, D.S., 1991, Treatment of tuberculosis by private general practitioners in India., Tubercle 72, 284-290. |

| [24] | Hong, Y.P., Kwon, D.W., Kim, S.J., Chang, S.C., Kang, M.K., Lee, E.P., Moon, H.D., and Lew, W.J., 1995, Survey of knowledge, attitudes and practices for tuberculosis among general practitioners., Tubercle and Lung Disease 76, 431-435. |

| [25] | Marsh, D., Hashim, R., Hassany, F., Hussain, N., Iqbal, Z., Irfanullah, A., Islam, N., Jalisi, F., Janoo, J., Kamal, K., Kara, A., Khan, A., Khan, R., Mirza, O., Mubin, T., Pirzada, F., Rizvi, N., Hussain, A., Ansari, G., Siddiqui, A. and Luby, S., 1996, Front-line management practices in urban Sindh, Pakistan., Tubercle and Lung Disease 77, 86-92. |

| [26] | Salami, A.K., Oluboyo, P.O., 2003, Management outcome of pulmonary tuberculosis: A nine year review in Ilorin., West Afr J Med 22, 114-119. |

| [27] | Scholten, J.N., Fujiwara, P.I., and Frieden, T.R., 1999, Prevalence and factors associated with tuberculosis infection among new school entrants, New York City, 1991-1993., Int J Tuberculosis Lung Dis 3, 31-41. |

| [28] | Ukwuaja, K.N., Ifebunadu, N.A., Osakwe, P.C., and Alobu, I., 2013, Tuberculosis Treatment Outcome and its Determinants in a Tertiary care setting in Southeastern Nigeria., Niger Postgrad Med J 20(2), 125-129. |

| [29] | Federal Ministry of Health, National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control program of Nigeria, 2008, Revised Workers manual ( 5th ed.), Abuja. |

| [30] | Kumar, D. ,2001, Planning a Role for Private Practitioners in TB Control: Obstacles and Opportunities. The Communication Initiative .http://www.comminit.com/st 2001/sld-3395.html: 1-4. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML