-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2014; 4(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20140401.01

Prevalence of Premenstrual Syndrome and Its Impact on Quality of Life among University Medical Students, Al Qassim University, KSA

Manal Ahmad Al-Batanony1, Sultan Fahad AL-Nohair2

1Public Health and Community Medicine department, Menoufiya faculty of Medicine, Menoufiya University, Egypt, Family and Community Medicine department, Unaiza Collage of medicine, Al-Qassim university, KSA

2Family and Community Medicine department, College of Medicine, Al-Qassim University, KSA

Correspondence to: Manal Ahmad Al-Batanony, Public Health and Community Medicine department, Menoufiya faculty of Medicine, Menoufiya University, Egypt, Family and Community Medicine department, Unaiza Collage of medicine, Al-Qassim university, KSA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) involves a variety of physical, emotional and psychological symptoms experienced by some women during the late luteal phase of menstrual cycle (7-14 days prior to menstruation). The symptoms of PMS seem to worsen as menstruation approaches and subside at the onset or after days of menstruation, and a symptom-free phase usually occurs following menses. The group of women with the severest premenstrual symptoms and impairment of social and role functioning often meet the diagnostic criteria for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a severe form of PMS. Objectives: To determine the prevalence of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) between university medical students, and to evaluate the impact of the condition on their quality of life (QOL). Methodology: A cross-sectional study included unmarried medical students aged 18-25 years with regular menstrual period for the last 6 months. Socio-demographic data, DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association) criteria questionnaire for PM/PMDD as well as the daily record of the severity of PMS problems scale (DRSP) was collected for each student for two prospective cycles. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) data questionnaire was collected on medical outcome study Short Form 36 (SF-36) after taking informed consent from the students. Results: The prevalence of PMS among the studied group was 78.5%, of them, 5.9% had severe form of PMS. This study showed that the burden of PMS/PMDD on health-related quality of life was on mental and emotional health-related quality of life domains beside on physical health-related quality of life domains as the students with PMS reported a poorer health-related quality of life as measured by SF-36 than those without PMS. Conclusion: PMS/PMDD is a prevalent, yet undertreated, disorder among medical students in KSA, which adversely affected their quality of life.

Keywords: Pre-menstrual syndrome, University medical students, Quality of life

Cite this paper: Manal Ahmad Al-Batanony, Sultan Fahad AL-Nohair, Prevalence of Premenstrual Syndrome and Its Impact on Quality of Life among University Medical Students, Al Qassim University, KSA, Public Health Research, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20140401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Premenstrual disorders include premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) which are characterized by the cyclical recurrence of a variable constellation of physical, psychological, and/or behavioral symptoms which appears in the luteal phase and subsides with the onset of menstrual flow[1-4]. It is a debilitating condition, causing social and occupational impairment in the lives of affected women comparable to that associated with major depressive disorder, and with a burden of disease and disability adjusted life years lost on a par with major recognized disorders[5,6]. Hence, the quality of life as well as economic implications of PMS should not be overlooked.The common symptoms of PMS and PMDD include breast tenderness, bodyaches, headache, bloating, sleep disturbances, appetite change, poor concentration, decreased interest, social withdrawal, irritability, mood swings, anxiety/tension, depression, and feeling out of control[7]. Of these, six symptoms identified as core symptoms suggesting that clinical diagnosis of PMS can be developed around a core symptom group. The identified core symptoms are: anxiety/tension, mood swings, aches, appetite/food cravings, cramps, and decreased interest in activities[8]. However, although it has been estimated that a high proportion of women in reproductive age (up to 90%) experience some degree of premenstrual symptoms, the diagnosis of PMS or PMDD is assigned to those women whose lives are significantly affected by moderate to severe symptoms[9].Premenstrual symptoms might cause several difficulties for women including impairment in physical functioning, psychological health and severe dysfunction in social or occupational realms[10]. In young adolescents symptoms might particularly affect school functions, and social interactions in a negative way[11]. Previous studies have also shown that women with premenstrual disorders have a poor health-related quality of life[12-14]. A comprehensive review of the literature was done by Rapkin and Winer[13]. It was distinguished four types of studies that evaluated the PMS/PMDD effect on health-related quality of life and for instance reported that ‘the affective, behavioral and physical symptoms of PMDD have been shown to adversely affect health-related quality of life to a disabling degree, especially regarding interpersonal relationships with family members and partner’ or ‘women with PMDD suffer impairment that is as severe as women with chronic clinical depression’. Women with PMDD were affected by luteal phase adjustment to social and leisure activities which become worse than women with other types of depression[13]. There are no national data on PMS and again there are no data available on the relationship between premenstrual syndrome and poor quality of life among Saudi females. Moreover, studies of premenstrual syndrome among Middle East females as a general are lacking.

2. Objectives

- 1- To determine the prevalence of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) between university medical students, 2- To assess the severity of PMS.3- To evaluate the burden of the condition on the quality of life (QOL).

3. Subjects and Methods

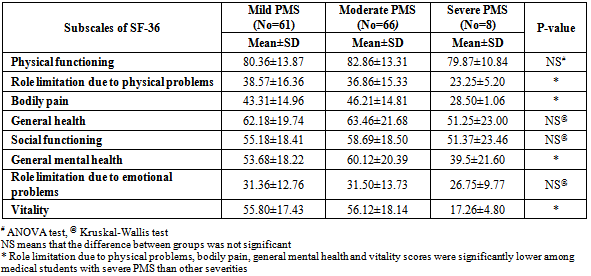

- A cross-sectional study was carried out over 172 university medical students at Al-Qassim University from March till the end of May 2013. All unmarried medical students at the college of Medicine aged 18-25 years old from 1st to 5th grade, after menarche by at least one year, with regular menstrual period for the last 6 months who agreed to participate in the study were the target group. Students with irregular menstrual cycle, current major medical and psychological problems, those receiving hormonal therapy and experiencing a catastrophe shortly before or during the study were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from each student before participation. Approval of Al-Qasim University Research Ethics Committee was obtained. A self-administered pre-designed questionnaire was used to collect data about: 1- Demographic characteristics (age, grade, and marital status), menstrual history (age of menarche, severity of menstrual bleeding, menstrual period duration and presence of dysmenorrhea), and family history of PMS. 2- DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association)[15] criteria questionnaire for PMDD/PMS for two prospective menstrual cycles. This questionnaire consists of 11 symptoms that according to the DSM-IV, participants should have at least five symptoms of this questionnaire and at least one of these symptoms should have been from the first symptoms (core symptoms). The symptoms should be present a week before menses and remit a few days after the onset of menses. Each symptom has a scale from 1-6, where 1= not at all, 2=minimal, 3= mild, 4= moderate, 5= severe, 6= extreme. 3- The daily record of the severity of PMS problems scale includes 21 items grouped into 11 domains and 3 occupational productivity questions. Each item is rated on a scale of 1-6. These items represent the criteria of PMS that have been described in DSM-IV[15]. Participants were asked to complete this form for two prospective menstrual cycles. The highest score of each symptom was accounted, and the total score of PMS was calculated as the sum of the symptom’s score divided by the number of symptom. This score was converted to percentage and a score between 0- less than 33% represented mild form of PMS, 33-66% was moderate form and more than 66% was accounted as a severe form of PMS[16]. 4- Health-related quality of life data will be collected on medical outcome study Short Form 36 (SF-36). It is a generic instrument used as a general indicator of health status covering physical and mental concepts by 36 questions. Physical component contains four subscales which are physical functioning, role limitation due to physical problems, bodily pain, and general health perceptions, where mental component contains four subscales which are social function, general mental health, role limitation due to emotional problems and vitality. Each question is rated from 0-100 which the higher score representing the most favorable score and the highest level of health[17]. All questionnaires were handled out to the students in the classrooms and collected after being filled. Data was analyzed by using the Statistical Package of the Social Science (SPSS) software for Windows, version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, III). Independent student t-test and Mann Whiteny U test were used for comparison between two groups of quantitative normally distributed and not normally distributed variables; respectively. ANOVA test and Kruskal Wallis test were used for comparison between more than two groups of quantitative normally distributed and not normally distributed variables; respectively. Qualitative data were expressed as number and percentage (No and %) where chi-square test was used. The results were considered significant at P<0.05. To demonstrate reliability and validity of the daily record of the severity of PMS problems scale, Cronbach’s alpha score was calculated (the result was 0.88).

4. Results

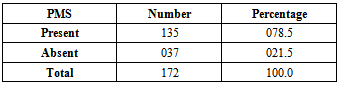

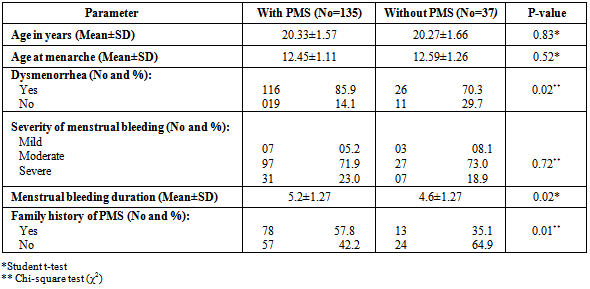

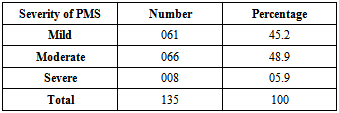

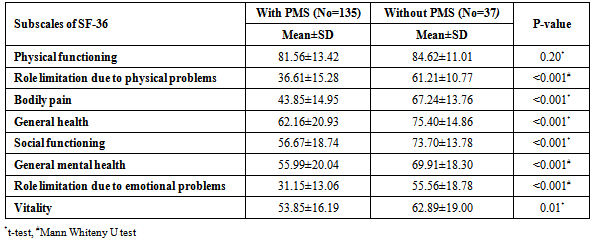

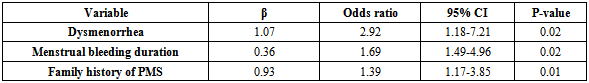

- The prevalence of PMS among the studied group was 78.5% (table 1), of them, 45.2% showed mild PMS while moderate PMS represented 48.9% and 5.9% had severe form of PMS (table 3). Among those with PMS, the mean aged was 20.33±1.57, where the mean age at menarche was 12.45±1.11 and the mean menstrual period duration was 5.2±1.02. Girls having PMS reported significant higher prevalence of dysmenorrhea (85.9%), more menstrual bleeding duration (5.2±1.27) and positive family history of PMS (57.8%) than those without PMS (table 2). The mean of scores in all subscales of SF-36 in the PMS group was significantly lower than those without PMS except for physical functioning subscale (table 4). With increasing the severity of PMS, the scores of quality of life items by SF-36 became lower reaching a significant level for role limitation due to physical problems, bodily pain, general mental health and vitality (table 5). PMS was significantly associated with dysmenorrheal (P=0.02), positive family history of PMS (P=0.01) and increased duration of menstrual bleeding (P=0.02) (table 6).

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

- The prevalence of PMS among the studied group was 78.5%. This result agrees with the study among Chinese female undergraduates and reported PMS with prevalence of 76%[18]. In Sri Lanka among a sample of adolescents, individuals with PMS experienced 65.7%[19]. A cross-sectional survey of 1295 rural adolescent girls aged 13-19 years in Malaysia[20] showed that most participants (63.1%) identified themselves as having PMS. A prevalence of 61.4% was also found among 10-17 years old adolescent girls in Ankara, Turkey[21]. Similarly, in a population-based study on 1395 women aged 15-45 years in Brazil found that the prevalence of self reported PMS was 60.3%[22]. A lower prevalence of 51% was reported in Pakistan between medical students[23]. Faraway prevalence was reported in some studies, that 27% of a student sample in a university in Ethiopia met criteria for PMS[24]. PMS prevalence rates of 16.4% and 17.3% were observed between adolescent school girls in United Arab Emirates[11] and 971 American women aged from 18-45 years[25]; respectively. Higher prevalence than that found in this study was shown in other studies. In an adolescent sample, all participants (N=78) had at least one premenstrual symptom of minimal severity[26]. Among Iranian female university students, the prevalence of premenstrual syndrome was 98.2%[27]. It was found that more than 98% of their respondents in Thailand suffered from one or more premenstrual symptoms[28]. In another study, it was observed that 92% of the studied Chinese women experienced some PMS symptoms. This difference in the prevalence may be revealed to the difference in the study group and/or the difference in the used questionnaire to assess PMS[29]. This study revealed that 48.9% of those having PMS suffered from a moderate form where only 5.9% had a severe form of PMS. This result is near to that obtained among Iranian adolescent girls where 62.2% of the studied individuals had moderate PMS and 8.8% had severe form[30]. However, the majority of the studied group in Pakistanian[23] and Turkish[21] studies had a mild form of PMS (59.5% and 49.5%; respectively). This difference may be related to individual variations and changes in the pain threshold from person to person. This study showed that the burden of PMS/PMDD on health-related quality of life was on mental and emotional health-related quality of life domains as well as on physical health-related quality of life domains as the students with PMS reported a poorer health-related quality of life as measured by SF-36 than those without PMS. This is similar to the results obtained in a cross-sectional study among students in high schools in Iran[31]. Also, the previous investigations in Iran[30] and Pakistan[23] used the SF-36 to measure health-related QOL in female adolescents who suffered from PMS and both found that QOL was significantly lower in the affected group. Moreover, in United Arab Emirates[11], it was proved that premenstrual syndrome has had a significant suggestive influence on the QOL of adolescent school girls. Also, it was found that women at risk for PMS/PMDD were significantly more likely to report limitations than women with no indication of PMS in all health related quality of life areas except for two physical functioning items and one mental health item[32]. In contrary, in USA, it was found that the burden of PMDD was greater on mental and emotional health-related quality of life domains than on physical health-related quality of life domains[33]. This difference between our result and the last study, may be referred to that it is argued that physical symptoms were found to be psychological in nature by some authors[34] and/or due to different life styles, socio-demographic status or cultures between the studied groups.Dysmenorrhea was extensive among the study subjects and had a significant and independent association with PMS in the multivariate analysis. Other significantly associated risk factors were family history of PMS and higher duration of menstrual bleeding. A significant relationship of PMS with dysmenorrheal and family history of PMS was found similar to studies from Pakistan[23], UAE[11] and USA[35].

6. Conclusions

- PMS/PMDD is a prevalent, yet undertreated, disorder among medical students in KSA, which adversely affected their quality of life. This finding suggested that health and educational authorities need to recognize the problem and provide appropriate, tangible and emotional support as well as giving more attention to psychological methods as counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy for medical students with premenstrual disorders (especially for those with PMDD). It is believed that improvements in QOL reduces the complications associated with this disorder, or at least makes it more tolerable. Further studies can incorporate QOL not only as an outcome measures but also as a part of the inclusion criteria for the selection of subjects like comparing different medical and psychological treatment for those with PMDD.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML