-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2013; 3(4): 98-107

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20130304.03

Factors Affecting Late Presentation for HIV/AIDS Care in Southwest Ethiopia: A Case Control Study

Hailay A Gesesew, Fessehaye A Tesfamichael, Birtukan T Adamu

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia

Correspondence to: Hailay A Gesesew, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Late presentation for HIV/AIDS care may occur either as a result of late testing for HIV or delayed presentation to HIV care after getting tested. Identification of different risk factors associated with late HIV/AIDS care is essential to target interventions aimed at favoring early entrance into HIV/AIDS care. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess factors associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia. Institution based unmatched case-control study triangulated with qualitative method was conducted at Jimma University Specialized Hospital and Jimma Health Center. A sample of 103 cases and 206 controls were selected using a consecutive sampling technique. Purposively, selected health workers working in an Anti Retroviral Therapy clinic and selected HIV positive individuals who were attending an Anti Retroviral Therapy clinic for the first time were included in an in-depth interview. The primary statistical methodology used was logistic regression analysis and all analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software for windows version 16. Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis and triangulated with quantitative findings. The following were correlated with increased risk of delayed HIV/AIDS care:Those who were divorced or separated (AOR=3.7, CI: 1.3-10.4), could formally read and write (AOR=3.7, CI: 1.6-8.7), perceived HIV as curable (AOR= 2.7, CI: 1.3-5.4), got tested by voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) (AOR=2.5, CI: 1.2-5.4), had symptoms of HIV at time of diagnosis (AOR= 4.9, CI: 2.3-10.9), had chronic health problems (AOR= 2.7, CI: 1.2-5.9), had contact with a commercial sex worker (AOR= 3.00, CI: 1.4-6.5) and alcohol users (AOR= 3.8, CI: 1.8-7.9) as compared with their counterparts. The qualitative findings also showed that HIV stigma, non disclosure, low awareness, substance use, having contact with commercial sex workers, and poor linkage after HIV testing were the major barriers for late presentation for HIV/AIDS care.In this study being separated or divorced, being educated, having signs and symptoms of HIV at diagnosis, having chronic health problems and having behavioral problems upon HIV diagnosis were risk factors for late HIV/AIDS care. So, efforts to reduce late initiation of HIV/AIDS care should focus on addressing these risk factors.

Keywords: ‘Late presentation’, ‘Late testing’, ‘HIV/AIDS care’, ‘Associated factor’

Cite this paper: Hailay A Gesesew, Fessehaye A Tesfamichael, Birtukan T Adamu, Factors Affecting Late Presentation for HIV/AIDS Care in Southwest Ethiopia: A Case Control Study, Public Health Research, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 98-107. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20130304.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- AIDS is a dreaded disease with no effective vaccine or drug therapy to completely eliminate the infection[1]. Worldwide, a total of 33.3 million people are infected with HIV of which one third are aged between 15-24 years. Africa, Asia and Latin America are the major continents affected with the disease[2]. A total of 22.9 million people are infected with HIV in Africa with the highest number in Sub Saharan Africa[3]. In Ethiopia, approximately 1.2 million people are infected with HIV but only 268,934 patients were alive and on Anti Retroviral Therapy (ART) at the end of 2010[4]. In Jimma town, the estimated prevalence of HIV in 2004 was around 7%[5]. Late presentation for HIV/AIDS care may occur because HIV-infected persons are not aware of their risk of infection and fail to seek testing, or, even if aware of their risk, do not seek testing and thus face significant barriers to access HIV testing. In addition, patients may not immediately seek or get access to medical care upon receiving their first HIV positive test result[6]. A current literature review reveals a lack of consensus regarding the definition of delayed HIV diagnosis. However, several definitions have been used to date. Some defined Delayed HIV Diagnosis (DHD) as the diagnosis of an AIDS defining condition occurring either before or concomitantly to an AIDS diagnosis[7], and during the subsequent six months[6,8] .Other definitions used CD4 cell count < 200 cells/µl (10) or < 350 cells/µl[9]. According to the 1993 expanded AIDS-surveillance case definition, persons who presented with a CD4 cell count <200 cells/µl and/or with an AIDS-defining disease are considered to be a delayer for HIV/AIDS care[10]. In Ethiopia, late presentation for HIV/AIDS care is considered when HIV infected individuals come for ART care with CD4 below 200 cells/µl and /or WHO stages 3 or 4[11].Reducing the time between infection and the initiation of ART is important to decrease progression of the infection and to facilitate immunological recovery. Moreover, delays in HIV/AIDS care have serious public health implications due to loss of opportunities to prevent further transmission through effective ART[11], and initiating treatment for HIV infection at an advanced stage leads to poorer outcomes than with early treatment[11,12]. It also has economic implications for health services and society[13]. A large proportion of HIV infected individuals in the developed world, roughly 15%-43%, present at clinics for care with advanced or severe disease i.e. WHO stage 3 or 4 or CD4 lymphocyte count ≤ 200 cells/µl) (14). In Spain, 56.3% of new diagnoses of HIV infection with CD4<350 cells/ µl between 2003 and 2007 required treatment at the time of diagnosis and 30.2% of these presented severe immune suppression (CD4<200 cells/µl)[15]. Little is known in low income countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, about the proportion or characteristics of HIV-infected individuals who present late for care at clinics irrespective of many reasons[16]. A cross-sectional analysis in Uganda explains that over one-third (40%) of the diagnoses were categorized as late presenters with WHO stage 3 or 4[16]. A study conducted in Gabon showed that 45% of the patients had a CD4 cell count <200 cells/µL at HIV diagnosis[17]. The prevalence of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in Ethiopia is not known but a situational analysis done from January 1 to August 30/2011 before data collection showed a prevalence of 33.1% in Jimma Health Center and 38.4% in Jimma University Specialized Hospital (JUSH). A sole study in Ethiopia regarding factors associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care was done in South Wollo zone hospitals using a case control paradigm[11]. This study demonstrates that low awareness, non disclosure, perceived ART side effects, and HIV stigma were identified as being the major barriers. Given the majority of these studies were conducted in hospitals, the analyses of late presentation in ambulatory clinics would not represent the characteristics of HIV positives who presented in the health center setting. Additionally, the effect of some factors such as chronic illness and sex inconsistence in late presentation for HIV/AIDS care were not seen in the Ethiopian study. Lastly, in so far as this research is entirely related to the population in Ethiopia, further researches should be done. This study was done in Jimma town ART site health institutions named Jimma University Specialized Hospital (JUSH) and Jimma Health Center found in South west Ethiopia to overcome the above limitations. Additionally, identification of different risk factors associated with late HIV/AIDS care is essential in order to guide program planning and organizing care for HIV/AIDS cases and to target interventions aimed at favoring early entrance into HIV/AIDS care. It is expected that identifying these risk factors would enable to reverse the trend of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in Ethiopia, and thereby overcome its immediate and long term consequences.

2. Methods and Participants

- Unmatched case-control study triangulated with qualitative method was conducted from January 07- March 08, 2012 in Jimma University Specialized Hospital (JUSH) and Jimma health center in Jimma town, south west Ethiopia. In both settings, Voluntary Counseling and testing (VCT), Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT), ART and opportunistic infections (OIs) treatment services are available. The study population constituted sampled cases and controls of people living with HIV who visited ART clinic for the first time in the hospital and health center. Cases were HIV positive individuals aged 15 years and above, who had WHO clinical stage III or IV, irrespective of CD4 lymphocyte count; or a CD4 lymphocyte count of less than 200/ µl irrespective of clinical staging at the time of first presentation to the ART clinics of the institution. Whereas, controls were HIV positive individuals aged 15 years and above who had WHO stage I or II and a CD4 lymphocyte count of >= 200/ µl at the time of first presentation to the ART clinics of the institution[11]. For quantitative study, sample size was calculated with Open - Epi Version 2.3 software assuming 95% confidence level, 80% power and the proportion of those having perceived HIV/AIDS related stigma among controls to be 9.4%[11], estimated odds ratio of 2.8[11] and control: case ratio of 2:1. This gives a sample size of 98 cases and 196 controls. Adding 5 % for non-response rate, the sample size was 103 cases and 206 controls. The sample size was allocated for both institutions proportional to their total number of cases and controls. Consecutive sampling technique was applied to select the number of cases and controls. For the qualitative method, 7 health workers engaged in HIV/AIDS care and 3 cases and 6 controls were involved in the in-depth interview which later was triangulated with the quantitative finding. Purposive sampling technique was used to recruit the participants for the in-depth interview.A pretested structured interviewer administered questionnaire was used to collect data on the socio- demographic and economic, HIV testing, health service and behavioral factors. Stigma was assessed by using a 4 point likert scaled 23 items tool[25]. Using these items, over all mean was calculated and dichotomized as high or low perceived stigma if above or below the calculated mean respectively. This questionnaire was developed in English and was translated to local languages (Afan Oromo and Amharic) by persons who did have similar work experience and was back translated to English by other person to check for its consistency. Data were collected by ART trained nurses working in ART clinics of respective institution. To triangulate the findings of the case-case control study, an interview guide prepared to assess the most common factors associated with HIV/AIDS such as behavioral, institutional and VCT related barriers were used to conduct an in-depth interview. The interview was recorded using a voice recorder and field notes were taken.Data were entered into Epi data version-3.1 computer software and was double entered for verification. The entered data were exported into SPSS version- 16 statistical software to be cleaned and analyzed. A descriptive analysis was conducted to check for outliers, inconsistencies and missed values. Bivariate analysis was employed to see the association between each exposure and outcome variables. To control the effect of confounding factors, variables that had statistically significant association with bivariate analysis at 20% level of significance were entered in to a multiple logistic regression model using backward stepwise method. Wald test with 5% level of significance was used to identify independent predictors of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care. In addition, the presence of two way interaction between variables was tested. Co-llinearity diagnosis was calculated for the following variables: cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and chat chewing. Finally, goodness of fit of the final model was checked using Hosmer and Lemeshow statistics and likelihood ratio. For the in-depth interview findings, after transcription was made, similar themes as per their theme were arranged using thematic analysis and triangulated with the quantitative findings. Ethical clearance was obtained from the health research and post graduate coordinating office of the College of Public Health and Medical Sciences of Jimma University. Oral consent was obtained from the study participants.Operational Definitions ● Time to present for HIV care- Presentation of the participants to HIV/AIDS care dichotomized as early or late.● Early presentation for HIV/AIDS care – when HIV positive individuals (age 15 years and above) came with WHO stage I or II and a CD4 lymphocyte count of 200 cells/ µl or more at the time of first presentation to the ART clinics of the institution. ● Late presentation for HIV/AIDS care- when HIV positive individuals (age 15 years and above) come with WHO clinical stage III or IV irrespective of CD4 lymphocyte count or a CD4 lymphocyte count of less than 200 cells/ µl irrespective of clinical staging at the time of first presentation to the ART clinics of the institution.● Occupational status: categorized as formally employed (civil servants, participants employed in nongovernmental or other organizations), self employed (farmers, merchants, have their own work, unemployed (housewife and students) and others (daily labor).● Read and write (informal) - Participants who got education outside of a standard school setting for those who did not take formal education so far.● Income- below or above average annual income of Ethiopia ( 1005 USD )[26]● Ever drug abuse: is a patterned use of a substance (drug) in which the user consumes the substance in amounts or with methods neither approved nor advised by medical professionals in his life time. E.g. narcotics, stimulants, depressants (sedatives), hallucinogens, or cannabis. ● Stigma- high is considered as when individuals scored above the mean where as low is considered as when individuals scored below.

3. Results

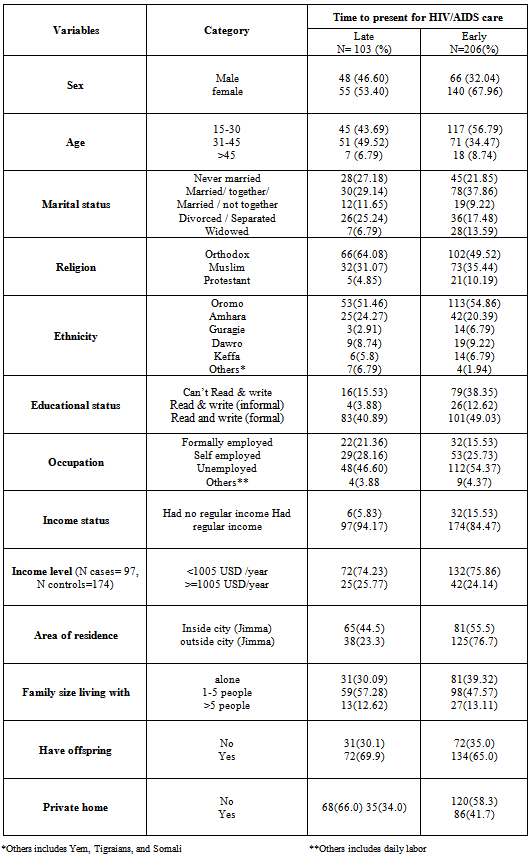

- Socio-demographic and economic characteristics of the study participantsA total of 103 cases and 206 controls were included in the study making a response rate of 100%. Fifty five (53.4%) cases and 140 (67.9%) controls were females of whom 7(12.7%) study cases and 13(9.3%) controls were pregnant. The median age of study cases and controls was 33 years and 30 years respectively. The majority of study cases (49.5%) and controls (56.8%) were in the age category of 31-45 years and 15-30 years respectively. Oromo by ethnicity, orthodox by religion, married or living together by marital status and those who could read and write formally dominated both study groups (Table 1). Among the socio-demographic and economic variables, male sex, aged between 31-45 years, could read and write formally, had regular income and lived inside Jimma town were associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in the bivariate analysis.

3.1. HIV/AIDS Testing Factors

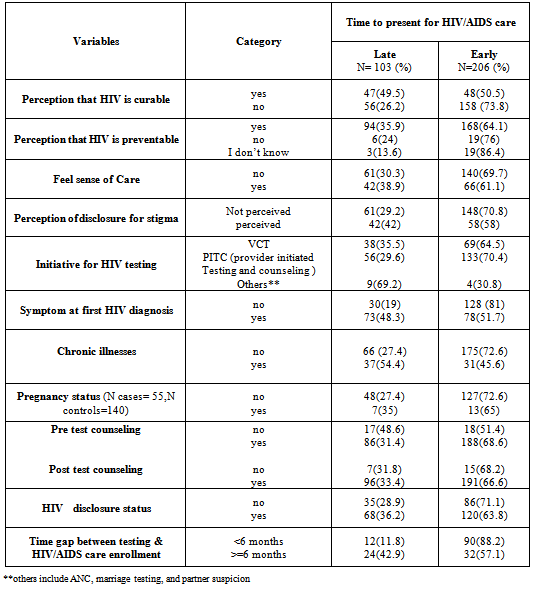

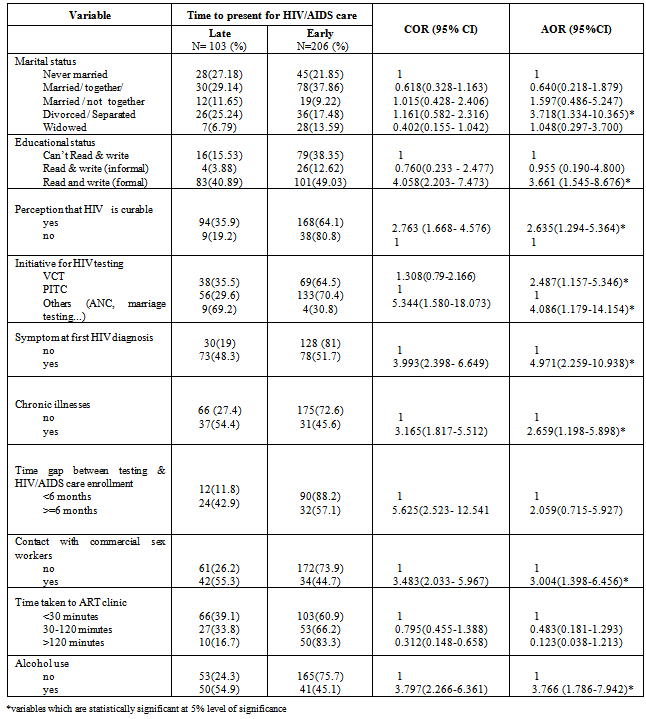

- Of the HIV/AIDS testing related factors, perceiving HIV as curable, perceiving HIV as preventable, perceiving stigma associated with disclosure, got tested by VCT, had symptoms at first HIV diagnosis, had chronic illnesses and did not receive pre test counseling were associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in the bivariate analysis (Table 2). Regarding the reliability of stigma scale, Cronbatch’s α of its items was 0.89.

3.2. Health Service Factors

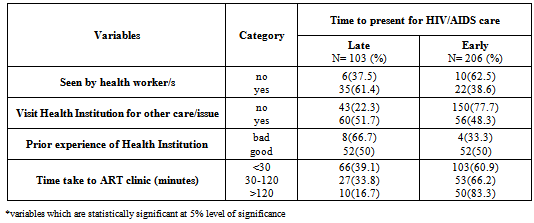

- With regard to health service related factors, visiting a health institution for any issue and time taken to reach ART clinic greater than 2 hours were associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in the bivariate analysis unlike what is seen by health worker/s, prior experience and way of travelling to ART (Table 3).

3.3. Behavioral Factors

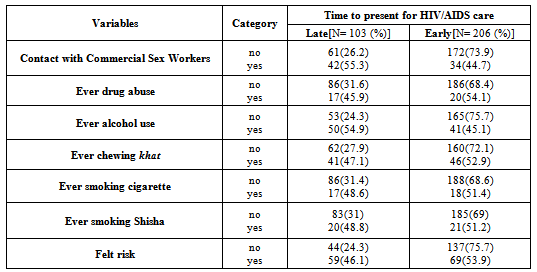

- Among behavioral related factors, having contact with commercial sex workers, alcohol users, chewing chat, smoking cigarette, smoking Shisha, perceived risk and other risk categories such as blood contact and having an HIV positive mother were found to be associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in the bivariate analysis unlike drug abuse (Table 4).

|

|

|

|

3.4. Independently Associated Factors to Late Presentation for HIV/AIDS Care

- Finally, being divorced/separated, being able to read and write formally, presentation of symptom/s at first HIV diagnosis, got tested by VCT, chronic illness, having contact with commercial sex worker, ever alcohol users, having an extended gap between testing & HIV/AIDS care enrollment and their being a long time to reach ART clinic were risk factors of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care (Table 5). Among the socio-demographic and economic factors, being separated/divorced was associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care (AOR=3.7, 95%CI: 1.3-10.4). As to educational status, the odds of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care among those who can formally read and write were 3.7 times higher than those who were illiterate (AOR=3.7, 95%CI: 1.6-8.7) (Table 5). The qualitative findings also showed that those educated individuals presented late. For instance, one female ART nurse from JUSH stated that “….Look, we observed educated people coming late. Why? Most of them want take ART outside nearby ART clinic even they know their status ….may be for fear of stigma.’’ With regard to HIV testing factors, study participants perceiving HIV/AIDS as being a curable disease presented late for HIV/AIDS care (AOR=2.6, 95%CI: 1.3-5.4). Getting tested by VCT was associated with increasing risk of coming late to HIV/AIDS care (AOR=2.49, 95%CI: 1.2-5.4) (Table 5). Most of the participants in the in-depth interview also supported this issue. For example, one male ART nurse from Jimma Health Center said, “….Nowadays, I did not see the effect of VCT, because there is poor linkage after individuals received their HIV positive result. My friend for example knew his status during epiphany day but came to clinic so many months later with stretcher after he falls down. But it is rare to see patients coming late if get tested by PITC (Provider Initiated Testing and Counseling).” The result also showed that the odds of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care among those with symptom/s at first HIV diagnosis were 4.9 times higher than among those without symptom/s at first HIV diagnosis (AOR=4.9, 95%CI: 2.3-10.9) as they were with chronic health problem/s (AOR=2.7,95%CI:1.2-5.9) (Table 5). Among behavioral related issues, having contact with commercial sex workers increased the likelihood of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care (AOR=3, 95%CI: 1.4-6.5) (Table 5). This is also supported by the in-depth interview finding. One 27 years old female HIV infected control from JUSH said, “….The commercial sex workers never disclose their status because they did not want to lose their clients and their job at all. So if individuals contact with them, they may not come to clinic before showing signs and symptoms.” The odds of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care among ever alcohol users were 3.8 times higher as compared to non users (AOR=3.8,95%CI: 1.8-7.9) (Table 5). This result is also congruent with the qualitative finding obtained. For example, one 29 years old female HIV infected case from Jimma health center said, “….Let alone they are infected with HIV (smokers, drinkers and chewers), these people are hopeless, and they do not have bright future. So it is difficult to expect them to come early before debilitating.” Apart from the above qualitative findings, HIV perceived stigma, non disclosure, low awareness of HIV/AIDS, unavailability of transportation to ART clinic/ VCT center, and poor linkage after getting HIV test were the major barriers for late presentation for HIV/AIDS care.

|

4. Discussion

- This is the first study in Ethiopia exploring factors associated with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in mixed institutions i.e. health center and hospital. But only one study was done in two hospitals about the issue. Since it is difficult to determine the time of infection, rapid progression to AIDS[7] or low CD4+cell count at diagnosis [9,11] have been used to define late presentation HIV/AIDS care. Using a case control comparison, the findings of this study shed important light as to why a large number of HIV positive people in Jimma come late for HIV/AIDS care. In line with other studies[10, 11, 16, 19-23], being divorced/ separated, having the capacity to read and write formally, having symptom/s at first HIV diagnosis, getting tested by VCT, having chronic health problem/s, having contact with commercial sex workers, alcohol users, the presence of an extended gap between testing & HIV/AIDS care enrollment and length of time to present at ART clinic, increases the likelihood of late presentation for HIV/ AIDS care. Along with socio-demographic and economic factors, delayed HIV/AIDS care has been correlated with sex in most studies[16, 18]. Regarding marital status, separated / divorced individuals were found to be 3.7 times more likely to present late for HIV/AIDS care than those who never married which is consistent with a study done in Uganda[16]. This could be explained by the fact that separated/divorced individuals might feel anger, develop stress/depression and face economical crises (especially if they have children) and all of those may inhibit the time of HIV/AIDS care seeking. HIV positive individuals who could formally read and write (AOR=3.7, 95%CI: 1.6-8.7) were more likely to present late for HIV/AIDS care. This is similar to the retrospective study conducted in France (AOR=3.1, 95% CI: 1.0–9.6) irrespective of the difference in demographics and health care utilization (19). But it is inconsistent (p=0.052) with the study conducted in Venezuela[20]. Perhaps the Venezuelan study was not adjusted for time taken to ART and fear of stigma or the difference in study design (cross sectional study design was conducted in the Venezuelan study).Among HIV testing related factors, those HIV positive individuals who perceived that HIV is curable were associated with increased risk of coming late for HIV/AIDS care. The curability perception might be related to traditional healers and these individuals may try this option first, instead of going to an HIV clinic[17, 21]. Testing on self initiative increased the likelihood of late presentation than testing for health related reasons which is consistent with a study done in San Francisco, USA[22]. This may be explained by the very poor linkage after got tested by VCT. Besides, those who got tested by Provider Initiated Testing and Counseling (PITC) might link care early for symptom relief. HIV positive individuals who had symptoms/sickness at HIV diagnosis were significantly associated (AOR=4.9, 95%CI: 2.3-10.9) with late presentation for HIV/AIDS care; similar with the finding of the studies done in Ethiopia and France [11, 19]. This could be partly explained by people living with HIV/AIDS presenting late in the course of their disease are more likely to be diagnosed at advanced stages of disease progression. Similarly, HIV positive individuals who had chronic health problem/s at HIV diagnosis (AOR=2.7, 95%CI: 1.2-5.9) were associated with late presentation for HIV / AIDS care; consistent with the finding of the study done in Birmingham, United Kingdom[23] irrespective of the difference in demographic and health service status. This could be due to decreasing the immunity of infected individuals by these chronic diseases more likely to be diagnosed at advanced stages of disease progression or that most symptoms associated with HIV could be explained by the complication of the chronic disease and unrecognized need for HIV testing[23].Lastly, as to behavioral related factors is concerned, having contact with commercial sex workers (AOR=3.01, 95%CI: 1.4-6.5) increases the likelihood of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care and this is supported by a study done in America and in Venezuela[10, 20]. This could be explained as having unprotected sex with multiple sexual partners can lead to multiplication of different types of viral strains and this may rapidly step up to an advanced stage. Another possible explanation for this occurrence could be due to less behavioral preparedness for initiating HIV/AIDS care. In this case, most individuals who have contact with commercial sex workers might also be substance users[11, 24]. Finally, alcohol users did have an increased chance of coming late for HIV/AIDS care (AOR=3.8, 95%CI: 1.8-7.9) than non users and this is supported by Ethiopian and Ugandan studies[11, 16]. This might imply that there is lack of readiness for behavior change among people living with HIV/AIDS to start the HIV/AIDS care early[11]. These people do not want to stop consuming alcohol although it is highly recommended at ART centers for those who are taking ART. To the reverse, more non-drinkers presented late in another study conducted in Uganda[16]. This might be presented as drinkers feel risk and linked to care after early testing as compared to non drinkers.The study has its own strengths and limitations. The combination of both qualitative and quantitative methods as well as the involvement of people living with HIV/AIDS and health workers allowed a cross-validation of findings, and the study design, itself, could be a good aspect of the study. The analyses of late presentation would represent the characteristics of HIV positives who attended in the health centers and hospitals. Despite the above strengths, the study has the following limitations. As most questions related to the time before or at diagnosis, recall bias could be expected. There might be social desirability and interviewer bias as the setting is ART clinic and the data collectors were clinical staffs. This study is not also accountable for the rate of disease progression. Because delayed presentation to HIV/AIDS care was also defined using clinical measures, a disproportionate number of rapid progresses could have introduced information bias. Due to budget limitation, symptoms at HIV testing and ever alcohol use were not included in the sample size determination. Inclusion of pregnant women in the study population could lead to selection bias because literature has widely suggested that pregnancy is associated with greater interaction with healthcare and also a personally heightened need for linkage to HIV care. However, since the number is small, it is not expected to cause substantial changes in results. Lastly, missing data of some variables hindered results on late presentation for HIV/AIDS care.

5. Conclusions

- In conclusion, HIV positive participants who were separated/ divorced could read and write formally, who have sign/symptoms and chronic health problems at HIV diagnosis had a probability of presenting late for HIV/AIDS care. Besides, those who used alcohol and those who had contact with commercial sex workers were more prone to late presentation for HIV/AIDS care. So, the promotion and evaluation of HIV routine testing of patients attending chronic health illnesses in health centers and hospitals should be strengthened. A ‘test and treat’ strategy to reduce delayed presenters for HIV/AIDS care should be strengthened i.e. the poor linkage after testing through VCT should be quite strong. In addition, modified testing strategies for specific for commercial sex workers (high-risk populations) should be implemented. For researchers, further study should be done in children below age of 15 years. It is also better to conduct this study using large samples in order to detect common predictors of late testers and/or late presenters as risks of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care. Additional study should be done on educational status, gender and alcohol use as there were inconsistencies. Lastly, the unknown prevalence of late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in Ethiopia should be studied and its definition should be clearly explained to the country context.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- Our earnest gratitude goes to Department of Epidemiology, Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Jimma Health Center, data collectors and the study participants of both institutions for their cooperation and assistance. We also thank Jimma University for funding the study. Special thank goes to Professor Jeffrey M. Robins, Harvard Medical School, who exhaustively and meticulously edit the manuscript.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML