-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2013; 3(3): 43-49

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20130303.03

Prevalence of Tobacco Use and Associated Behaviours and Exposures among the Youth in Kenya: Report of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in 2007

William K. Maina1, Joyce N. Nato2, Monica A. Okoth1, Dorcas J. Kiptui1, Ahmed O. Ogwell3

1Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, Nairobi, Kenya

2World Health Organization, Kenya Country Office, Nairobi, Kenya

3World Health Organization, Regional office of Africa, Brazzaville, Congo

Correspondence to: William K. Maina, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) 2007 was conducted to provide information on tobacco use among the youth which would guide the development of tobacco control programmes targeting this specific age group. This was a school-based cross-sectional study involving children aged 13-15 years old. The study was based on the GYTS which applies a standardized methodology for sampling, preparing of the questionnaire, carrying out field procedures, and data processing. One out of every four students had ever smoked, 1 out of 10 students was a current smoker, and slightly over a tenth (12.8%) of all students used other forms of tobacco other than cigarettes. Boys were twice likely to be current smokers than girls (12.7% versus 6.5%). Overall 18.6% of students had used any form of tobacco with girls more likely to use smokeless tobacco than boys. The GYTS was developed to provide data on youth tobacco use. Data in this report can be used as baseline measures for future evaluation of the tobacco control programs established for the implementation of the WHO FCTC and the Tobacco Control Act 2007 in Kenya.

Keywords: Prevalence,Tobacco Use, Youths, Smoking, School

Cite this paper: William K. Maina, Joyce N. Nato, Monica A. Okoth, Dorcas J. Kiptui, Ahmed O. Ogwell, Prevalence of Tobacco Use and Associated Behaviours and Exposures among the Youth in Kenya: Report of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey in 2007, Public Health Research, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 43-49. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20130303.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Public health efforts to control tobacco in Kenya started back in 1995. However the first draft law was done in 2001 but was never tabled before parliament. In order to reach out for wider stakeholder support for tobacco control, the Ministry of Health (MOH) established a multi-sectoral National Tobacco Free Initiative Committee (NTFIC) in 2002. The role of this committee was to advice the MOH on all matters of tobacco control and also to organize awareness and advocacy activities particularly during the World No Tobacco days[1].The World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) was adopted in 2003[2]. This global public health treaty addresses one of the main preventable causes of chronic disease and death worldwide[3]. Kenya signed and ratified this treaty in 2004 becoming the second country after Norway to sign and ratify it on the same day[4].The WHO FCTC urges countries to establish programs for national, regional, and global surveillance[2]. TheGlobal Tobacco Surveillance System (GTSS) includes the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), the Global School Personnel Survey (GSPS) and the Global Health Professionals Survey (GHPS). The GTSS was developed by WHO in conjunction with the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Canadian Public Health Association to assist member states in establishing continuous periodic tobacco control surveillance and monitoring[5, 6]. The GYTS surveillance system is intended to enhance the capacity of countries to design, implement, and evaluate tobacco control and prevention programs.Several studies have attempted to establish the situation of tobacco use in Kenya. The first GYTS was conducted in 2001 which indicated that 13% of students aged 13 to 15 years currently used any tobacco products with 7.2% being current smokers[7]. The 2003 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey (KDHS) found out that 23% of adult males and less than 1% of females aged 18 years and above were current smokers[8]. Kwamanga et al found out that among secondary school students in Nairobi, 12.4% of males and 6.4% of females were current smokers[9]. Many studies have found out that children initiate smoking at ages as low as 10 years but the average age of initiation in Kenya has been found to be 15 years[10,11].The purpose of this paper is to present the findings of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) conducted in Kenya in 2007 and discuss the trend of tobacco use among the youth. It provides valuable information on components to consider for effective tobacco control programmes at the national and county levels.

2. Methods

- This was a school-based cross-sectional study conducted in the month of March 2007 and involved children aged 13-15 years old who were enrolled in standard 7, standard 8, and Form 1 and 2 classes. The study was based on the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) which applies a standardized methodology for constructing sampling frames, selecting schools and classes, preparing the questionnaire, carrying out field procedures, and data processing[12].

2.1. Sampling

- All schools containing standard 7, standard 8, form 1, and form 2 with an enrollment of at least 40 or more students were included in the sampling frame. A two-stage cluster sample design was used to produce a representative sample of students in these classes. The first-stage sampling frame consisted of all schools with standard 7, standard 8, form 1, and form 2. A list of all eligible schools was provided by the Ministry of Education from which schools were selected with a probability proportional to enrolment size. This meant that large schools were more likely to be selected than small ones. Sixty-seven schools with a target survey population of students were selected. 25 schools were selected in Nairobi an urban area, 16 in Mombasa an urban area, with strong influence from tourism and 24 from the rest of the country, which is predominantly rural setting. This facilitated a representation from both the urban and rural areas.The second sampling stage consisted of systematic equal probability sampling of classes from each school that participated in the survey. All classes in the selected schools were included in the sampling frame. In each selected school, the number of streams in each class, standards 7, 8 or form 1 and 2 were listed. From this list, classes were randomly selected based on the random start provided by CDC on the school level forms. In each school, depending on the number of classes listed one or two or three of those classes were selected. In each class selected, all students present were eligible for the survey.

2.2. Development, Pre-testing and Administration of the Country Specific Questionnaire

- The GYTS questionnaire used in Kenya consisted of 60 ‘core’ questions which allow for comparison between countries and regions. All questions had responses to choose from and apart from four questions that asked for background information such as age, gender, class and religion, the rest solicited information on the use of tobacco i.e. prevalence, access, brands of cigarettes and other tobacco products, knowledge and attitude towards smoking, environmental tobacco exposure, cessation, media and advertising and school curriculum. Ethical approval to conduct the study was provided by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health.Several tobacco use indicators were enquired in the GYTS questionnaire including: ever smoked cigarettes even if it is “one or two puffs”, current cigarette smoking either in the last “1 or more days” during the past 30 days, on how many days did one smoke cigarettes; ever used any other form of tobacco other than cigarettes; current use of tobacco products other than cigarettes; the likelihood of initiation of cigarette smoking in the next year among never smokers if offered a cigarette by a friend; exposure to cigarette smoke in public places and duration of exposure; exposure to tobacco advertisements and anti-tobacco messages; attitude towards ban on smoking in public places among others.All the questions were in English which is the language of instruction in all learning institutions in the country. The questionnaire was pre-tested with 20 students aged 13 to 15 years in Kiambu District which has both rural and urban settings before it was administered in schools to test students’ understanding of the questions. All students who attended school on the day of the survey were eligible for participation by filling a self-administered questionnaire. Anonymity in terms of student, class and school was maintained throughout the process.

2.3. Data Analysis

- Data was entered and analyzed using EPI Info software while SUDAAN (Version 10.0) software package for statistical analysis of correlated data, was used to compute standard errors of the estimates and produced 95% confidence intervals. During analysis, a weighting factor was used to reflect the likelihood of sampling each student and to reduce bias by compensating for differing patterns of non-response by school, class or student and variation in the probability of selection at the school and class levels. To determine differences between subpopulations t-Tests were used. Differences between prevalence estimates were considered statistically significant if the t-Test p-value was <0.05. All analyses conducted in this study were gender stratified.During analysis, a weighting factor was applied to each student record to adjust for non-response and the varying probabilities of selection. A weight was associated with each questionnaire to reflect the likelihood of sampling each student and to reduce bias by compensating for differing patterns of non-response.The weight (W) used for estimation is given by:W=W1*W2*f1*f2*f3*f4Where, W1=the inverse of the probability of selecting the school; W2=the inverse of the probability of selecting the classroom within the school; f1 =a school-level non-response adjustment factor calculated by school size category (small, medium, large); f2=a class-levelnon-response adjustment factor calculated for each school; f3=a student-level non response adjustment factor calculated by class; f4=a post stratification adjustment factor calculated by form.

3. Results

- All the 65 schools that were sampled participated in the survey. A total of 12,378 students were sampled but only 11,069 (89.4%) completed usable questionnaires (Nairobi (4,422), Mombasa (3,118), and rest of the country (3,529)).

3.1. Prevalence of Tobacco Use

- At the time the GYTS was conducted, almost 1 in every 4 (24.4%) of students in Kenya reported that they had ever smoked with boys (33%) more than twice as likely to have ever smoked as girls (15.5%). Nearly 1 out 10 (9.8%) of all students aged 13 to 15 years were current smokers, similarly boys (12.7%) were twice as likely to be currently smokers than girls (6.5%). Slightly over a tenth (12.8%) of all students surveyed used other forms of tobacco other than cigarettes smoking; girls (14.5%) were more likely use other tobacco products than boys (10.7%). Overall, 18.6% of students had used any form of tobacco with no difference in rate of use between boys (18.2%) and girls (18.2%).Of all the current smokers, 12.1% reported that they always had or felt like having a cigarette first thing in the morning (suggesting tobacco dependency) and 9.5% said they will definitely smoke cigarettes 5 years from then (boys at 7.3% and girls at 14.4%). Among the never smoked, 19.4% (boys at 19.3% and girls at 19.2%) reported that they could start smoking in the next one year (See table 1). Current smoking was directly associated with male gender (OR=1.95; 95CI[1.76-2.18]) and having smoking parents (OR=2.38).

3.2. Cessation

- Amongst the students who currently smoked, nearly 8 out of every 10 current smokers (79.2%) wanted to stop smoking now, 76% said they had tried to stop during the past one year but failed and 84.9% had received help to stop smoking (See table 1). Of all those who had ever smoked but were not current smokers, 67.6% had successfully quit for more than three years. Half of those who had stopped smoking said they did it to improve their health. Only 30.4% of ever smokers received help or advice to help stop smoking. Advice was mainly sought from friends (19.4%), from program or professional (18.7%) and least from family member (13.6%).

|

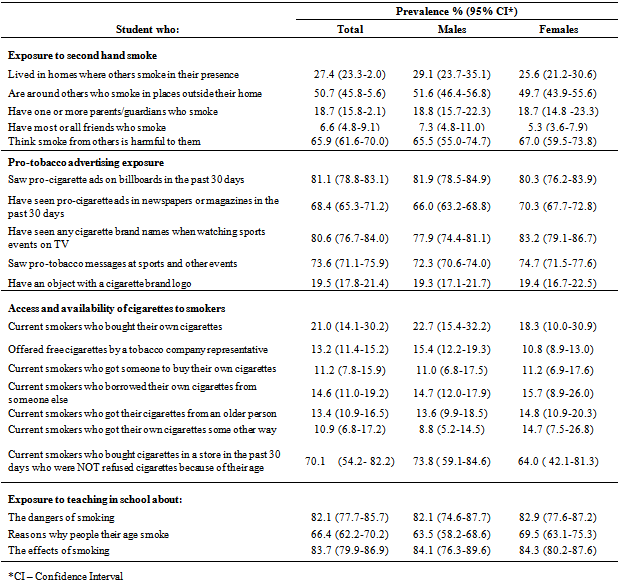

3.3. Exposure to Second Hand Smoke

- More than a quarter (27.4%) of all school children in Kenya live in homes where others smoke in their presence; 50.7% are around others who smoke in places outside their home ; 52.8% think smoking should be banned from public places; 65.9% think smoke from others is harmful to them; 18.7% have one or more parents who smoke and 6.6% have most or all friends who smoke (See table 2).

3.4. Exposure to Media and Advertising of Tobacco Products

- More than 8 out 10 (81.1%) students in Kenya reported that they saw pro-cigarette adverts on billboards in the past 30 days prior to the survey; 68.4% had seen pro-cigarette adverts in newspapers or magazines in the past 30 days to the survey; 80.6 reported that they had seen any cigarette brand names when watching sports events on television; 73.6% saw pro-tobacco messages at sports and other events and 19.5% had an object (that is, hat, t-shirt, knapsack, and so on) with a cigarette brand logo. Free cigarettes had been offered to 13.2% of students by a tobacco company representative, where boys were significantly more likely to be offered free cigarettes than girls (See table 2).

3.5. Access and Availability of Cigarettes to Smokers

- Among students who were current smokers, 21% bought their own cigarettes; while the rest got them from someone else. Of those who said they bought their cigarettes in a store in the past 30 days, 70.1% were not refused cigarettes because of their age. Almost three out ten (29.5%) of students who are current smokers smoke in a friend’s house and 12% do smoke ion social events (Table 2).

|

|

4. Discussion

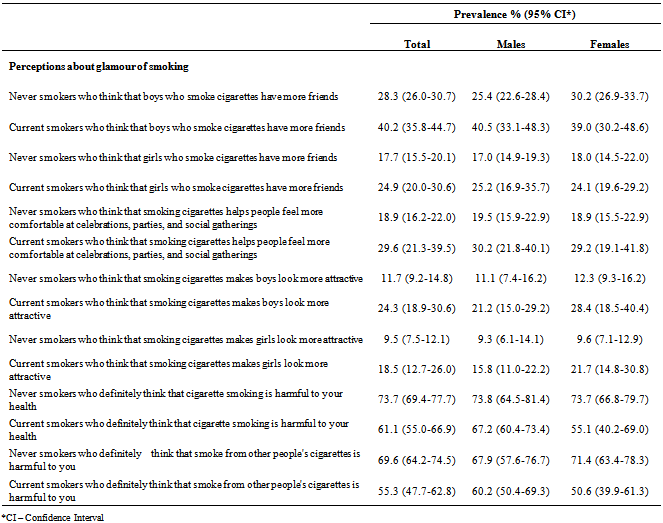

- The GYTS provides valuable information on the prevalence of tobacco use among the youth and factors that could have contributed to its initiation. The GYTS also provides indicators for measuring achievement of several WHO FCTC articles such as surveillance and monitoring, prevalence, exposure to secondhand smoke, school based tobacco control, cessation, media and advertising, and minor’s access and availability[12,13].This study provides the best estimation of the prevalence of tobacco use among young people in Kenya. The study found out that nearly 1 in 10 (9.8%) school children aged 13 to 15 years in Kenya was a current smoker while nearly 1 in 4 (24.4%) reported that they had ever smoked. As has been demonstrated in other studies, males have a higher prevalence of tobacco use than females. Kwamanga et al found out that 10.5% of students in secondary schools in Nairobi were current smoker (boys at 12.4% and girls at 6.4%) (9). Rudatsikira et al found an overall smoking prevalence of 2.9% among adolescents in Ethiopia with males rated at 4.5% in males and 0.4% in females[14]. Mpabulungi and Muula have reported overall smoking prevalence of 5.6% with boys at 6.7% and girls 3.3%[15]. Although smoking among female students in Kenya is significantly lower than their male colleagues if compared to developed countries, it is quite high compared to other African countries with similar traditional, cultural and social norms that discourage cigarette smoking habits among females[16]. The significance of prevalence data on tobacco use in the youth is important both to assess tobacco as a risk factor and understand control measures for prevention of those diseases that are associated with tobacco use.The prevalence of tobacco use among students aged 13-15 years had significantly rose since the last GYTS was conducted in Kenya in 2001[17]. This rapid increase in prevalence of tobacco use could be attributed partly to increased tobacco industry advertisement campaign. Tobacco advertisements, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS) has been found to increase smoking initiation among youths[17]. Enactment and enforcement of comprehensive bans on TAPS according to Article 13 of the WHO FCTC and its guidelines can substantially reduce tobacco consumption and protect the youths from industry marketing tactics.A significant number of students (79.2%) who were current smokers stated that they wanted to quit now and many of them (76%) had tried to quit in the last one year but failed. Nearly 70% of ever smoked and who had quit smoking were successful. It is therefore, important to implement cessation programmes that target young people so as to provide education and help. Both tobacco control and tobacco cessation activities continue to remain important public and individual health issues and need to be incorporated into all levels of health care and social life.The study showed that children between 13 to 15 years are exposed to second hand smoke either at home (27.4%) or in places outside home (50.7%). A significantly high percentage of current smokers, were exposed to second-hand smoke, as compared to never smokers, both in their homes (61.8% versus 20.6%) and in public places (80.1% versus 45.3%). We can therefore infer that exposure to second hand smoke increases tendency to initiate smoke and reduce the chances of quitting smoking[18]. The promotion of smoke-free environments should be considered a potentially effective mechanism for decreasing smoking among young adultsMore than half of the children (52.8%) supported policies that ban smoking in public places as majority of them (65.9%) were aware that smoke from others is harmful to them. Banning of smoking in public places, including all indoor workplaces, schools and homes protects people from the harms of second-hand smoke, helps smokers quit and reduces youth smoking[17]. There is a growing amount of evidence that clean indoor air policies can have a positive effect on smokers as well as those at risk for exposure to environmental tobacco smoke[19].Current smokers were more likely to think that smokers have more friends (OR=1.4); that smokers feel more comfortable at social gatherings (OR=1.57); smokers look more attractive (OR= 2.08 for boys and OR=1.95 for girls). Health was the main reasons why most ‘ever smokers’ decided to quit (42.7%). Public education through mass media about the health dangers of tobacco use can influence an individual’s decision to start or continue to smoke. It is important to counteract the glamorous image of smoking portrayed by tobacco industry marketing. By reversing the erroneous perception that tobacco use is a low-risk habit, societal pressures will cause many individuals to choose not to use tobacco. Ultimately, the objective of anti-tobacco education and counter-advertising is to change social norms about tobacco use[16].There are three main limitations to the findings in this report. First, the sample surveyed was limited to youths attending school who may not be representative of all 13 to 15 year olds in Kenya. Second, the information gathered apply only to youths who were in school the day the survey was administered and completed. The school response rate was 100% in all sites while the student response rate was almost 90% in all sites therefore; bias due to absence or non-response is small. Third, data are based on self-reports of students, who may under- or over-report their use of tobacco. The extent of this bias cannot be determined in this particular group; however, responses to tobacco questions on surveys similar to GYTS have shown good test-retest reliability[20].Young adulthood represents a critical time in the transition from adolescence to adulthood when changes in risk-taking behaviors such as experimenting with smoking become apparent. It has been established in some developed countries that over 90% of adults who smoke report that they started during adolescence[9]. It is during the early adulthood that non-smokers may be initiating smoking while young smokers may be transitioning from experimentation to regular smoking and later transitioning from non-dependent smokers to dependent smokers[21]. The implementation of effective prevention and cessation programmes for children and adolescents is extremely critical.

5. Conclusions

- The increase in the rate of use of tobacco by young people should be a grave concern. The increase in smoking and use of other tobacco products noted among the girls calls for concerted efforts to implement gender sensitive approaches to tobacco control. The ratification of the WHO FCTC and enactment of the Tobacco Control Act 2007 by Kenya provides an opportunity to curtail increase in tobacco use among the youth. Repeating the GYTS in future will assist in monitoring if these tobacco control policies are being implemented and enforced.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Canadian Public Health Agency, National Cancer Institute, UNICEF, and the World Health Organization-Tobacco Free Initiative provided us with funds and technical support including data analysis. The Ministry of Education headquarters and the Nairobi City Directorate of Education gave us the authority to conduct this survey in all Kenyan schools. The Ministry of Health gave the Authority to conduct this study. The whole team in the division of non-communicable diseases in the Ministry of Health participated in field supervision of data collection. To all of you we acknowledge your priceless contribution.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML