-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2013; 3(3): 37-42

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20130303.02

Unmet Need for Family Planning: Experience from Urban and Rural Areas in Bangladesh

Rafiqul Islam, Ahmed Zohirul Islam, Mosiur Rahman

Department of Population Science and Human Resource Development, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh

Correspondence to: Ahmed Zohirul Islam, Department of Population Science and Human Resource Development, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

One-fourth of pregnancies are either unwanted or mistimed in Bangladesh.Unwanted births not only pose risk to child health and wellbeing but also force to rapid population growth in resource strapped countries. The objectives of this study are to examine the extent of unmet need for contraception in Bangladesh and to explore the differentials in unmet need by some selected characteristics of the reproductive aged women in rural-urban Bangladesh. This study utilizes BDHS 2004 data. Chi square test and logistic regression analysis are used here. The total unmet need for family planning among currently married women in Bangladesh is found to be 12%. Unmet need to space births in rural area is higher than in urban area. The significant predictors of unmet need for spacing and limiting births are found to be ever using family planning, discussing family planning matters with spouses, number of living children, intention to have last child, age and education in the rural area whereas, age, intention of having last child, ever use of any contraception and discussing family planning matters with spouses in urban area. Rural women especially young married women deserve special consideration because unmet need to space birth is highest among them.

Keywords: Family Planning, Contraception, Unmet Need, Spacing Birth, Limiting Birth

Cite this paper: Rafiqul Islam, Ahmed Zohirul Islam, Mosiur Rahman, Unmet Need for Family Planning: Experience from Urban and Rural Areas in Bangladesh, Public Health Research, Vol. 3 No. 3, 2013, pp. 37-42. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20130303.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Unmet need is a powerful concept for designing family planning programmes and has important implications for future population growth. More than 100 million women in less developed countries, or about 17% of all married women, would prefer to avoid pregnancy but are not using any form of family planning[1]. Unmet need for contraception can lead to unintended pregnancies, which pose risks to women, their families, and societies. In less developed countries, about one-fourth of pregnancies are unintended, that is, either unwanted or mistimed[2]. One particularly harmful consequence of unintended pregnancies is unsafe abortion. An estimated 18 million unsafe abortions take place each year in less developed regions, contributing to high rates of maternal death and injury in these regions[3].Bangladesh is a densely populated country of the world. Resource scarcity and subsistence-level economic conditions characterize the economy[4]. The total population is about 156 million about 36 % of the population lives on less than $1 a day[5]. Other indicators also reflect the poverty of the country: the literacy rate of the population aged five years and older is 43.1 % (males 53.9 and females 31.8 %) and life expectancy is 62 years for both males and females[6]. Although infant and child mortality levels have been declined, they are still high owing to relatively weak prenatal and postnatal services[7]. Despite these low socio-economic indicators, Bangladesh has achieved a high level of success in its family planning programme. Contraceptive use among married women in Bangladesh is increased gradually from 8% in 1975 to 61% in 2011, a greater than sevenfold increase in less than four decades. The total fertility rate (TFR) dropped by half, from about six children per woman to about three from 1975 to 2004. However, Bangladesh still has a long way to go to achieve the replacement level of fertility, i.e. about 2.1 children per woman, which the government hopes, will be achieved by the year 2015. The contraceptive prevalence rate(CPR) would have to rise to over 70% for this target to be reached[8]. Most recently, contraceptive use increased by 5% points in the past four years from 56% in 2007 to 61% in 2011. However, in 2011, 12% of currently married women in Bangladesh have an unmet need for family planning services [9]. The CPR could be raised by 12% if the programme is able to bring within its fold that segment of the population described as having an unmet contraceptive need. Recently 63% of women in developing countries use a method of family planning[10]. In 1960, that number was just 10%[11]. Despite this dramatic increase, about one in six married women still has an unmet need for family planning, that is, she wants to postpone her next pregnancy or stop having children altogether but, for whatever reason, is not using contraception[12]. As a consequence, 76 million women in developing countries still experience unintended pregnancies each year[13], and 19 million resort to unsafe abortions[14]. Therefore, the objectives of this study are to observe the extent of unmet need for contraception in Bangladesh and to explore the differentials in unmet need by some selected characteristics of the respondents between urban and rural areas.

1.1. Unmet Need: The Basic Concept

- Many women, who are sexually active would prefer to avoid becoming pregnant but nevertheless are not using any method of contraception, are considered to have an “unmet need” for family planning[15]. This concept basically points to the gap between some women’s reproductive intention and their contraceptive behavior. The standard formula of unmet need group includes all fecund women who are married or living union and thus presumed to be sexually active but are not using any method of contraception and who either do not want to have any more children (unmet need for limiting births) or want to postpone their next birth for at least two more years (unmet need for spacing births); the unmet need group also includes all pregnant married women whose pregnancies are mistimed or unwanted.

2. Sources of Data

- This study utilizes the data extracted from Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS) 2004, which employed nationally representative survey from 11,440 ever married women of age 10-49 covering 361 sample points’ of 122 urban areas and 239 rural areas throughout Bangladesh. Out of 11,440 ever-married samples 2586 and 8854 women are taken from urban and rural areas respectively.

3. Methodology

- In this study, unmet need is classified into two categories such as unmet need for spacing births and unmet need for limiting births. Unmet need for spacing birth includes pregnant women whose pregnancy was mistimed, amenorrheic women who are not using family planning and whose last birth was mistimed, and fecund women who are neither pregnant nor amenorrheic and who are not using any method of family planning and say they want to wait two or more years for their next birth. Moreover, unmet need for spacing birth includes fecund women who are not using any method of family planning and say they are unsure whether they want another child or who want another child but are unsure when to have the next birth. On the other hand, unmet need for limiting birth refers to pregnant women whose pregnancy was unwanted, amenorrheic women whose last child was unwanted, and fecund women who are neither pregnant nor amenorrheic, who are not using any method of family planning, and who want no more children. Excluded from the unmet need category are pregnant and amenorrheic women who became pregnant while using a method (these women are in need of a better method of contraception).Chi square test and logistic regression analysis are used to observe the effects of different covariates on unmet contraceptive need for spacing and limiting births. For this purpose two binary logistic models have been fitted for unmet need regarding spacing and limiting births separately for each urban, rural and all women of Bangladesh category. The response variable for the first model has two categories: unmet need for spacing (coded 1) and no unmet need for spacing (coded 0) and the response variable for the second model has also two categories: unmet need for limiting (coded 1) and no unmet need for limiting (coded 0).

4. Results

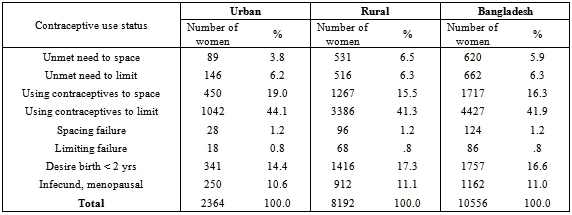

- The Table 1 elucidates that the total unmet need for family planning among currently married women in Bangladesh is 12.2 % out of which 5.9 % have unmet need for spacing births and 6.3 % want to limit births. However, unmet need to space births in the rural area is higher than that in the urban area. On the other hand unmet need to limit births is almost same for both urban (6.2 %) and rural (6.3 %) women.

|

|

|

4.1. Urban - Rural Differentials in Unmet Need for Contraception

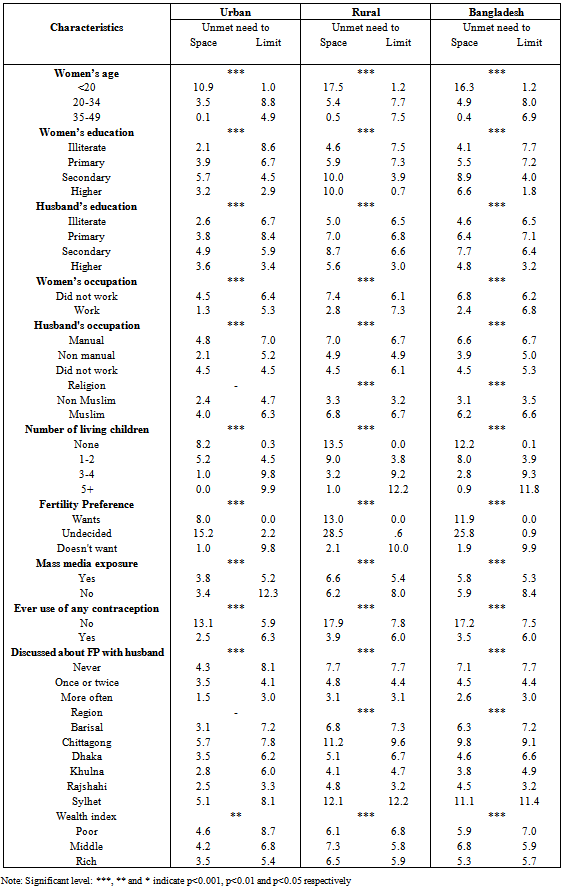

- Table 2 shows the percentage distribution of the women in the sample with an unmet contraceptive need. Unmet need for spacing births is higher among younger women, while unmet need for limiting childbearing is higher among older women. In each age group the level of unmet need among rural women is higher than that of urban women. But unmet need to limit births among urban women (8.8%) is higher than that of rural women (7.7%) only in the age group 20-34 years. Both urban and rural area as the education level increases the unmet need to limit birth decreases. Women who work for cash have less unmet need to space (1.3%) and to limit (5.3 %) births than their counterparts who do not work for cash in the urban area. Whereas rural women who work for cash have less unmet need to space (2.8%) but more unmet need to limit (7.3%) births than those women who do not work for cash.In the urban area women whose husband are non-manual workers ( Service man, business man etc., ) have less unmet need to space (2.1%) and limit (5.2%) births compared with those women whose husbands are manual workers (Day labours, farmers etc.,). This result is also true for the rural women and women allover the country. Muslim women have more unmet need (space and limit) for FP than their non-muslim counterparts both in the urban and rural area.As the number of living children increases the unmet need to space births is decreased but unmet need to limit births is increased among both urban and rural women. Women who access to mass media have 3.8% and 6.6% unmet need to space births among urban and rural women respectively, but unmet need to limit births is almost same for urban (5.2%) and rural (5.4%) women. Women who never use any contraception have higher unmet need for FP than those women who ever use any contraception allover the country. This is also true for both urban and rural women. Women who never discuss about FP with their husband have higher unmet need than their counterparts who discuss with their husband both in the urban and rural area. Unmet need (space and limit) is highest among women in Chittagong and Sylhet divisions (13.5% and 13.1% respectively) in the urban area and (20.8 % and 24.3 % respectively) in the rural area.

4.2. Determinants of Unmet Need for Contraception

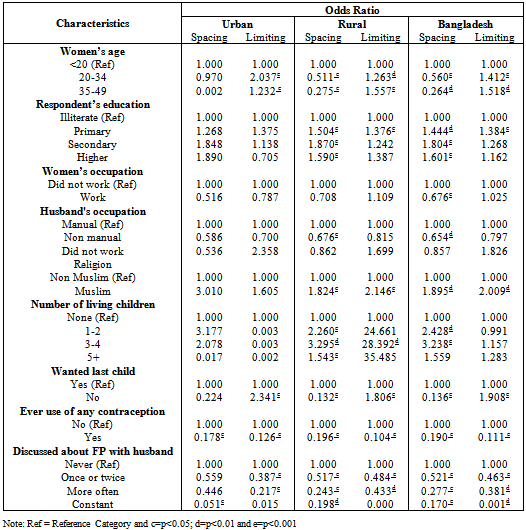

- We now wanted to see if there was any factors associated with unmet need in the urban and rural areas, and if any, how much did those factors contribute to unmet need. The ten predictor variables used are the same in both models. The results are presented in table 3.Unmet contraceptive need for spacing birth was concentrated among women in the under 20 year’s age group. In both urban and rural areas and for the country as a whole, the data shows that as the age increased unmet need to space birth gradually declined. For urban areas, there is no association between mother’s education and unmet need to space and limit birth. However in rural areas, women with primary schooling and those with a secondary and higher education had significantly higher (p<0.001) unmet need to space births. The probability of having an unmet need (Both space and limit) was significantly lower (p<0.001) where husbands and wife discussed family planning method and this was true for both urban and rural areas. Also it was significantly lower (p<0.001) among the ever users of any contraception. The no. of living children emerged as the best predictor of unmet contraceptive need in the rural areas. In the rural areas unmet need to space births was more than 1.5 times higher among women who had five or more children than those who had no children. By contrast, in the urban areas women who had five or more children unmet need to space births was 0.017 times lower than those who had no children and the difference was not statistically significant.

5. Discussion

- In this paper an attempt has been made to examine the proportion of women who are exposed to the risk of unwanted pregnancy but are not practicing contraception. In most societies this has been a very serious problem since the impact of unmet need on fertility over a period of time may be very significant even if the magnitude of unmet need at any point in time is small. The total unmet need for family planning among currently married women in Bangladesh is 12.2% out of which 5.9% have unmet need for spacing births and 6.3% want to limit births. Statistics on unmet need may understate the true demand for family planning. They often exclude unmarried women because it is difficult to collect reliable information[16,17]. Yet unmarried young people face great barriers to services and may have higher levels of unmet need than married women[18]. The standard definition of unmet need also fails to consider women who are using contraception but need a method that is more effective, safer, or a better fit with their personal circumstances[19]. However, Ferdousi et al. found in their study conducted at Sreepur upazila under Gazipur district in Bangladesh that 22.4% among rural women have unmet need of family planning[20]. In another study, among the married fecund women 7% have unmet need for contraceptive with 5% for spacing and 2% for limiting birth in kolkata, India[21]. Bhattacharya et al. observed that 42% unmet need of which 26 % % were limiters and 16% were spacers[22] and Saini et al. observed 26 % total unmet need with, 7% and 19% unmet need for spacing and limiting respectively[23]. Present study also represents that the unmet need to limit births is almost same for both urban and rural women; on the other hand, unmet need to space births in the rural area is higher than that in the urban area. Cost and accessibility have been identified as barriers to use of family planning services for poor, rural women[24]. In another study, Haque showed that about 16.03% of currently married adolescent women had an unmet need for contraceptive in Bangladesh it was higher in rural areas (17.4%) than in urban areas (12.6%). He also found that husband’s opposition and fear of side effects were the most cited causes for not using contraceptives[25]. Other research in sub-Saharan Africa has found that use of contraception increases if a woman has previously discussed contraception, been exposed to mass media about family planning, or approves of family planning [26, 27, 28].The main predictors of unmet need for spacing and limiting births were found to be ever use of family planning, husband-wife communication on family planning matters, number of living children and respondents age. It is quite evident that, if the 12% gap between ever use of contraception (70%) and current use (58%) could be bridged, the CPR would be close to 70% and the country might reach the replacement level of fertility. Therefore, in order of priority, the population programme should aim at motivating "drop-outs" to resume practicing contraception. The programme can do so through appropriate IEC (information, education and communication) measures, improved supervision, as well as by ensuring that the major reason for dropping out (half of the users in Bangladesh stop using contraceptive methods within the first 12 months of use), namely, side-effects, is duly addressed through better counseling as well as better management of side-effects. The programme certainly needs to give due consideration to improvements in the quality of care being offered to acceptors. This issue can be better addressed under the new service delivery strategy of providing services from static clinics, attended by paramedics in addition to field-workers. Also, the providers need to be given adequate training on counseling, screening and management of side-effects. Communication between husbands and wives on family planning matters is an important intermediate step along the path to their eventual adoption and the sustained use of family planning methods. The programme should be further strengthened and intensified in rural areas, where unmet need is highest. Community leaders should be more actively involved in the programme and it should give greater emphasis to longer-acting methods in order to address the unmet needs of high parity women. Higher parity women, using temporary methods or not practicing contraception at all, are potential candidates for permanent methods. The providers should motivate such women to accept permanent methods by explaining to them the relative advantages of permanent methods. The programme should intensify its efforts in the rural areas of the country in order to enhance accessibility to, and availability of, family planning methods. Young married women (less than 20 years of age) deserve special consideration because unmet need is highest among them, and their fertility is high. The programme should attach high priority to addressing the needs of these women by appropriate IEC measures and selective home visits.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML