-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2012; 2(6): 221-228

doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20120206.08

Looking beyond the Universal Health Coverage: Health Inequality, Medicalism and Dehealthism in India

Mohammad Akram

Department of Sociology and Social Work, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, 202002, (U.P.) India

Correspondence to: Mohammad Akram, Department of Sociology and Social Work, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, 202002, (U.P.) India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

India is world’s largest democracy having parliamentary form of government and federal structure. India is witnessing poor and differential achievements in increasing the life expectancy at birth and controlling infant mortality, maternal mortality and long and short term communicable and non-communicable morbidities among and within various states. The increasing hiatus in health achievements among groups in India amidst growing medicalisation and other policy reforms suggests prevalence of a deeper creeping malaise: health inequality. A new road map of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) for providing universal accessibility and affordability of healthcare is proposed. Taking a broad perspective on health and health care, this paper critically analyses the various provisions of proposed UHC in the context of unmet health needs and growing health inequality. It finds that the narrowing of health policies in post independence India is also responsible for perpetuation of inequalities in health. It also identifies specific hurdles in the path of achieving universal health, which are: poor primary health care, limited reach of public health, denial of basic health goods, out of pocket health expenditure and the growth of a vicious circle of ‘medicalism’ and ‘dehealthism’.

Keywords: Health care, Inequality, Health policy, Medicalism, Dehealthism

Cite this paper: Mohammad Akram, "Looking beyond the Universal Health Coverage: Health Inequality, Medicalism and Dehealthism in India", Public Health Research, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 221-228. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20120206.08.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Health is the basic human right of all the human beings. Health contributes to a person’s basic capability to function. Denial of health is not only denial of ‘good life-chance’, but also denial of fairness and justice[1]. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights stated in Article 25: ‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and wellbeing of himself and his family….’[2]. The Preamble to the World Health Organisation (WHO) constitution affirms that it is one of the fundamental rights of every human being to enjoy the highest attainable standards of health. Article 21 of the Constitution of India also identifies health as an integral aspect of human life[3]. Improving health status of the citizens is one of the most important goals of all the modern welfare governments. India has witnessed more than six decades of planned intervention in health since its independence. Although significant progress is made in developing proper health system and designing specific health programmes, the overall health outcome is not very encouraging. The health achievements in India are not uniform and health inequality is persisting. Initiatives taken at policy and planning level are unable to achieve the desired goal of ‘health for all’. This paper goes beyond the ‘bio-medical determinant of health approach’ and examines the merits and limitations of health policies and programmes in India, historically. Taking support from the secondary data, it establishes that health inequality is the most important challenge in health planning in India. It is imperative that any policy initiative relating to health care in India must have the potential to address this handicap. Hence, the proposed Universal Health Coverage (UHC) programme should also be seen from this perspective. This paper aims at exploring the major handicaps of the prevailing health policies and identifies the under current processes and mechanisms which act as impediments in achieving the health goals in the new millennium. This paper introduces a new term and concept, ‘dehealthism’, to explain some of the conditions caused by the politico-administrative apathy of the State to provide basic health goods (BHGs) to the people and to explain why it is necessary to break the vicious circle of ‘medicalism’ and ‘dehealthism’ for achieving sustainable health coverage for the citizens.

2. Methodology

- Empirical studies, in public health, frequently use epidemiological or social epidemiological methods. Macro level studies often use positivist statistical analysis. Ethnographic surveys or observations are also popular methods. However, critical knowledge is not limited to that which can be directly measured[4]. Critical realism is one such method which explores that which exists underneath the surface of observable phenomena and that can be ascertained through theoretical reasoning[5]. This paper is analytical in nature and uses critical realism as a method, as and when required.

3. Understanding Health

- The concepts of health, disease and treatment are related to the social structures of communities. Every culture, irrespective of its simplicity or complexity, has its own system of beliefs and practices concerning health and disease and evolves its own system of treatment to combat disease[6]. Definitions and conceptualisation of health may vary systemically among various social groups and it is likely that different accounts of health are drawn according to social circumstances[7]. The biomedical approach which dominated the medical thought till the end of nineteenth century and based on the ‘germ theory of disease’ views health as an ‘absence of diseases’. This approach almost ignores the role of environmental, psychological and other socio-cultural factors in defining health. The ecological approach views health as a dynamic equilibrium between man and his environment. For them, disease is maladjustment of the human organism to environment. The psychological approach states that health is not only related to the body but also to the mind and especially to the attitude of the individual. The socio-cultural approach considers health as a product of the social and community structure[8]. A holistic definition of health has been given by the World Health Organisation (WHO) which states that health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely an absence of disease or infirmity.Sociologists show how diseases could be differently understood, treated and experienced by demonstrating how disease is produced out of social organisation rather than nature, biology, or individual lifestyle choices[9]. A functional definition of health implies the ability of a person to participate in normal social roles. This may be contrasted with an experiential definition which takes sense of self into account[10]. Parsonian sociology emphasises the role of medicine in maintaining social harmony. Marxist approaches emphasise the causal role of economics in the production, distribution and treatment of disease. Medicine in a capitalist society reflects the characteristics of capitalism: it is profit-oriented, blame the victim, and reproduce the class structure in terms of the people who become doctors. Foucault, too, highlights the social role of medical knowledge in controlling populations, and like Parsons emphasises the diffused nature of power relationships in modern society. Also, like Parsons, he sees the professions, especially the helping professions, playing a key role in inducing individuals to comply with ‘normal’ social roles. For Foucault, modern societies are systems of organised surveillance with the catch being that individuals conduct the surveillance on themselves, having internalised ‘professional’ models of what is appropriate behaviour[9]. McKenzie, Pinger & Kotecki[11] have defined health as a dynamic state or condition that is multidimensional in nature and results from person’s adaptations to his/her environment. It is a resource for living and exists in varying degrees.

4. Health Inequalities

- Indian society is characterised by multiple inequalities. Whereas caste and gender divides find their roots in socio-historical complexes, class and spatial divides are related to uneven politico-economic developments. Cutting across the structural inequalities, ‘health inequality’ is a more contemporary challenge and possibly a consequence of the imbalances in development planning and economic designs. Health inequality, according to Sen[1], is one of the basic forms of inequality. Health inequality does not mean just some kind of health difference but the differences in health which adversely affect the opportunities and performances of those afflicted by it and are potentially avoidable through policy correction. It is a difference in which disadvantaged social groups (such as poor, racial / ethnic minorities, women or other groups that have persistently experienced social disadvantage or discrimination) systematically experience worse health or greater health risks than more advantaged social groups[12]. For Anand[13], inequalities in health have much negative consequences than the income inequalities as health has both instrumental and intrinsic value while income has only instrumental value. Some income inequalities are often considered acceptable by economists, as income incentives are required to elicit effort, skill, enterprise, and so on. But inequalities in health cause deprivation as they adversely affect the capability of people to function. The Black’s Report[14] is a landmark document in health inequality research, which brought about a paradigm shift in the discourse of health inequalities. Though it was well known that poorer sections of a community are more prone to disease and death but there were debates among the various groups regarding the cause. The Black’s report pointed out the complex effects of the economy and different forms of social organisation upon health and especially health of those who are economically in the lowest quintile. Link and Phelan[15] consider income inequality as the fundamental cause of disease. The Foucauldian approach towards health and disease can also be applied to understand the health inequalities. Michel Foucault calls attention to an important aspect of modern society: it is an administered society, in which professional groups define categories of people – the sick, the insane, the criminal, the deviant – on behalf of an administrative state. For Foucault, medicine is a product of the administrative state, policing normal behaviour, and using credentialed professionals to enforce compliance with the ‘normal’[9]. Thus health inequalities are also a product of the administrative state and its governmentality. In the democratic governments and welfare economies, government play most important role in policy making and deciding administrative priorities. Hence, a critical analysis of the government policies and planning designs is very important towards understanding the perpetual causation of health inequalities in modern societies.

5. Indicators of Health Inequality

- The Alma-Ata declaration and many other studies carried out in the last three decades have exposed the widespread inequalities inherent in the health condition of the people globally. The inequalities in health reveal not only the inequalities present in various other segments of the society but also indicate the discriminatory nature of various ongoing social, cultural and politico-economic processes.

5.1. Life Expectancy

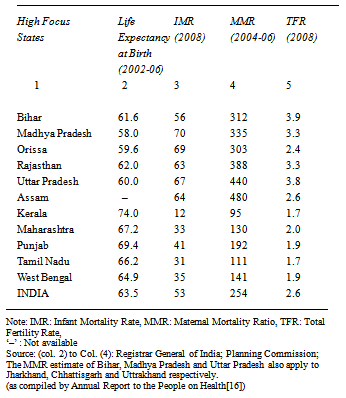

- The Annual Report to the People on Health[16] examines the progress made in the health sector in post independence era in India. In terms of life expectancy, child survival and maternal mortality, India’s performance has improved steadily. However there are wide divergences in the achievements across the states. There are inequities based on rural urban divides, gender imbalances and caste patterns. Life expectancy in India has more than doubled in the last sixty years. It increased from around 30 years at the time of independence to over 63.5 years in 2002-06. But the wide variance in performance across states is of special concern. While in Kerala, a person at the time of birth is expected to live for 74 years, the expectancy of life at birth in states like Assam, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh is in the range of 58-62 years, a level Kerala achieved during the period 1970-75. Globally India’s life expectancy is lower than the global average of 67.5 years. Some related figures are also given in Table 1.

5.2. Infant Mortality Rate (IMR)

- India’s infant mortality rate (IMR) too has shown a steady decline, from 129 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1971 to 53 in 2008[16]. The rate of decline has been slowing, from 19 points in the 1970s to 16 points in the current decade. The disparity between urban and rural is very high as urban IMR is 36 as compared to the rural IMR of 58. Wide spread disparities are also visible among various social categories in India. The IMR per 1000 live births among Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and Others is 66.4, 62.1, 56.6 and 57.0 respectively. The highest per cent of underweight children (Under 5 years age) is among SCs (54.5) and lowest is among Others (33.7). The other disparities or differential outcome among the high and low performing states is given in Table 1.

|

5.3. Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR)

- Maternal health is a key indicator of women’s health and status. Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) measures number of women aged 15-49 years dying due to maternal causes per 1,00,000 live births. India had a MMR of 460 in 1984 which declined to 254 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2004-2006. Great disparity is visible among the states even in MMR as Kerala and Tamil Nadu report low MMR of 95 and 111 respectively whereas other states have high MMR viz. Assam (480), Bihar/Jharkhand (312), Madhya Pradesh/ Chhattisgarh (335), Orissa (303), Rajasthan (388) and Uttar Pradesh/Uttarakhand (440)[16].

5.4. Communicable and Non-Communicable Diseases

- According to WHO, over 5.2 million people died in India of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like cardiovascular diseases, stroke, diabetes and cancer in 2008[17-18]. NCDs accounted for 53% of all deaths. Among men, 38% of the deaths were under 60 years, while among women it was 32%. Cardiovascular diseases accounted for 24% of all deaths, cancers (6%), respiratory disease (11%), diabetes (2%) and other NCDs (10%). NCDs are the major cause of death worldwide, killing more than 36 million in 2008. Cardiovascular diseases were responsible for 48% of these deaths, cancers (21%), chronic respiratory diseases (12%) and diabetes (3%). One of the findings shows that men and women in low-income countries are around three times more likely to die of NCDs before 60 years than in high-income countries[19]. These differential outcomes in health indicators are obvious indication of perpetuating health inequalities.

5.5. Antenatal Care

- Antenatal care (ANC) refers to pregnancy-related health care, which is usually provided by a doctor or health professional. The main purposes of antenatal care are to prevent certain complications, such as anaemia, and identify women with established pregnancy complications for treatment or transfer[20]. According to NFHS-3[21], almost one out of every five women in India did not receive any antenatal care for their last birth in the five years preceding the survey. Women not receiving antenatal care tend disproportionately to be older women, women having children of higher birth orders, scheduled tribe women, women with no education, and women in households with a low wealth index. The utilisation of antenatal care services differed greatly by state; Kerala and Tamil Nadu each ranked highest on four of the nine indicators but Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Rajasthan performed poorly on most of the indicators. Compared with Tamil Nadu, for example, where 96 percent of mothers had three or more antenatal care visits, only 17 percent of mothers in Bihar and 27 percent in Uttar Pradesh had three or more visits. For India as a whole, mothers of only 15 percent of births received all of the required components of antenatal care. This indicator ranges from a high of 64 percent in Kerala and 56 percent in Goa to a low of only 2 percent in Nagaland and 4 percent in Uttar Pradesh. Other states that performed almost as poorly as Uttar Pradesh and Nagaland on this indicator included Bihar, Arunachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Meghalaya, Rajasthan, and Mizoram, where only 6-9 percent of women received the recommended components of antenatal care. Kerala, followed closely by Goa, also outperformed all other states in terms of delivery care, with nearly all deliveries taking place in medical institutions and a similarly high percentage of deliveries assisted by a health professional. By contrast, only 12-20 percent of births were delivered in medical institutions in Nagaland, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Bihar. Only 25-29 percent of deliveries are assisted by health professionals in Nagaland, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Bihar[21].

5.6. Perpetuating Health Inequality

- Studies conducted at various levels suggest significant relationship between health achievement of the population and levels of income and educational attainment[14][21]. But, the correlations between health and education or income can’t necessarily lead us to the argument that removal of income and educational inequality is the precondition for removal of health inequality. The social determinant of health hypothesis (which finds its efficacy in western industrial and developed societies) is often selectively and discriminatorily used to support the arguments that health inequalities are simply the consequences of prevailing income and educational inequalities. Keeping in mind the poor performance of various states in India in removing poverty or attaining universal primary education, removal of health disparity will become a distant dream if we continue to believe in the above causation. Considering health as a completely dependent variable on income, education and life style factors legitimises the dismal regulation, administration and performance of the health care agencies in many of the low performing states and arbitrarily decided (read dictated) non-coherent health policy initiative of the central government (under the influence of external as well as internal market forces). Hence, it is necessary to critically examine the health policy priorities, processes and pattern of utilisation of health budgets in India.

6. Health Policy and Planning in India

- Policies come into existence and operate within political systems. They get guided not only by the state actors or societal needs, but also by the processes and mechanisms through which they come into existence and operate. For Walt[22], health policy is best understood by taking into consideration both processes and power. It involves exploring the role of the state, nationally and internationally, the actors within it, the external forces influencing it and the mechanism within the political system for participation in policy making. States are not always the sovereign decision makers, especially in economic sphere. Hence, it is important to take into consideration the important milestones in the development of health policy and planning in India.The Health Survey and Development Committee, also known as the Bhore committee[23], was appointed in 1943 and submitted its report in 1946 (before India got independence in 1947). This report is considered as the backbone of India’s health planning and programmes. It laid emphasis on integration of curative and preventive medicine at all levels. It suggested development of one primary health centre (PHC), manned by two doctors, one nurse, four public health nurses, four midwives, four trained dais, two sanitary inspectors, two health assistants, one pharmacist and fifteen other class IV employees, for a population of 40,000, and a secondary health centre, to provide support to PHC, and to coordinate and supervise their functioning. But the model recommended by the committee was never implemented in totality. The Mudaliar Committee (1962)[24] was appointed to access the performance of health sector since the submission of Bhore Committee report and it advised that the PHC’s, sub-divisional and district hospitals should be strengthened and they should provide preventive, curative and promotive services. Successively, the government of India appointed the Chadda committee, the Mukherji Committee, the Jugalwalla committee, the Kartar Singh Committee etc to address various issues related to health needs of the population[25].India had its first National Health Policy (NHP) in 1983 and before it only vertical health programmes like National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP), National Leprosy Eradication Programme, National Tuberculosis Control Programme, National Cancer Control Programme, etc existed, which were meant to address specific diseases. Besides these, some family planning and especially population control programmes were implemented. Health was never seen in a holistic perspective and the focus always remained on clinical treatment of ‘diseases’. The PHCs and sub-centres could never attract the attention that they deserved in many parts of the country even after the comprehensive recommendations made by the Alma Ata Declaration in 1978[26]. The first National Health Policy tried to revamp public health sector and specified the target of health for all by 2000 as its specific goal. But the government failed in realising the objectively defined targets of health and had to shift its priorities and directions under the structural adjustment programme (SAP) of 1990s. The decade of 1990s witnessed important shifts towards privatisation of healthcare. Three important things noticed then were: (1) increasing participation of voluntary organisations and private corporations; (2) increasing the quality of care at tertiary level; and (3) user charges even at the public healthcare centres. The second National Health Policy (2002)[27] came in the aftermath of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). It incorporated many of the health related goals and objectives suggested by the MDGs. Three important shifts of the policy were: great emphasis upon public health programmes through local self-government institutions; welcoming private sector in all areas of health activities; and, need for providing secondary and tertiary health service, to users from overseas who have the ability to pay. The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) was launched in 2005[28] to ensure participation of the local self-government institutions at village and panchayat level in a meaningful way. Some other priorities of the NRHM were: to regulate private sector including the informal rural practitioners; to ensure availability of quality services to citizens at reasonable cost; promotion of Public Private Partnerships (PPPs); and pooling social health insurance to provide health security. The policy shifts in last two decades clearly favour privatisation of healthcare services in India. It has also paved the path of health tourism for the health consumers from abroad. But the policies are almost silent in broadening the base or the scope of public health facilities at the national level. On the other hand, despite tall claims, the total fund allocation for implementing the various health programmes is dismal. Health financing is an important component of health systems’ architecture, and deals with sources of funding the health system. From a public policy point of view, it is desirable that health financing is so arranged that it reduces the overall out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure on health care, and protects against financial catastrophe related to health care. The global standard related to the ‘desirable’ limit of OOP to protect people from financial catastrophe is less than 15 per cent of total health spending. In contrast, in India, the OOP is to the tune of 71 per cent of total health spending[16]. The per capita public health spending is low in India, being among the five lowest in the world. Consequently, 3.2% Indians fall below the poverty line because of high medical bills. Further, about 70% of Indians spend their entire income on health care and purchasing drugs, according to WHO[29].It is also important to note here that the out-of-pocket expenditure on health care forms a major barrier to health seeking in India. According to the National Sample Survey Organisation, the year 2004 saw 28 per cent of ailments in rural areas go untreated due to financial reasons—up from 15 per cent in 1995–96. Similarly, in urban areas, 20 per cent of ailments were untreated due to financial reasons—up from 10 per cent in 1995-96[16]. However, the government has not done much to make the funds available to the needful. Responding to the initiative of WHO to find new means and ways for coverage of health needs of people, Government of India constituted a High Level Expert Group (HLEG) in 2010 for a new model of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) for providing universal accessibility and affordability of health care for all Indians[30].

7. Universal Health Coverage (UHC)

- Member States of the WHO committed in 2005 to develop their health financing systems so that all people have access to services and do not suffer financial hardship paying for them[31]. This goal was defined as universal coverage, sometimes called universal health coverage.

7.1. UHC at Global Level

- Across the world, more than 100 million people are pushed into poverty each year because of health care expenditures. This is an avoidable tragedy[32]. In striving for the goals of universal accessibility and affordability of health and health care governments face three fundamental questions[33]: 1. How is such a health system to be financed?2. How can they protect people from the financial consequences of ill-health and paying for health services?3. How can they encourage the optimum use of available resources?For WHO, the member States must also ensure that coverage is equitable and establish reliable means to monitor and evaluate progress. In this report, WHO outlines how countries can modify their financing systems to move more quickly towards universal coverage and to sustain those achievements. The report synthesises new research and lessons learnt from experience into a set of possible actions that countries at all stages of development can consider and adapt to their own needs. It suggests ways the international community can support efforts in low-income countries to achieve universal coverage[33].

7.2. UHC in India

- The High Level Expert Group (HLEG) constituted in 2011 for suggesting the model of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) for India had six terms of references (ToRs)[30]. Out of these, the most important are related to financing; resource generation; ensuring access to essential drugs, vaccines and medical technology; and, allowing participation of private for-profit sectors in delivery of health care in India. However, the ToRs are silent on what is meant by ‘health’, ‘coverage’ or ‘universal’. The government laid ToRs said nothing about the social determinants of health and these were included on the insistence of some members later. Above all, the ToRs completely ignored that WHO had suggested an equitable coverage and not an equal coverage to all. An equitable coverage is the best possible means to address the problems of health inequality that India is increasingly realising.

7.3. Recommendations of High Level Expert Group

- The recommendations[30] suggest that government should increase public expenditures on health from the current level of 1.2% of GDP to 3% of GDP by 2022. It proposes that every citizen should be entitled to essential primary, secondary and tertiary health care services that will be guaranteed by the Central government. The range of essential health care services offered as a National Health Package (NHP) will cover all common conditions and high-impact, cost-effective health care interventions. It also suggests developing effective contracting-in guidelines with adequate checks and balances for the provision of health care by the formal private sector and ensuring adequate numbers of trained health care providers and technical health care workers at different levels. It further recommends mechanisms for price controls and price regulation especially on essential drugs and services.A critical appreciation of the recommendations suggests that the HLEG has not kept in mind the deepening inequalities in health in India. It has also ignored the consistent poor performance of some of the states in improving health indicators or health care services. It says nothing about other possible ways to promote and sustain health as suggested by WHO. It is also silent on how to improve the circumstances in which people grow, live, work, and age. Some of these circumstances, as suggested by WHO are: education, housing, food and employment. Clearly, the HLEG has ignored the ‘public health’ aspect of the universal coverage and confined itself to the ‘medical’ and ‘insurance cover’ aspects. The report uses the terms ‘health’ and ‘medical’ interchangeably. Rather, it suitably replaces the term ‘health’ with ‘medical’. Consequently, all other terms, as identified earlier, get a specific and narrow meaning: ‘health care’ becomes ‘medical care’; ‘health delivery system’ becomes ‘medical services delivery system’; ‘health finance’ becomes ‘medical finance’ and unfortunately, the most important term, ‘health coverage’ becomes ‘medical coverage’. It has over expanded the word ‘universal’ to make the rich and upper strata equal stake holder with the poor and lower strata.

7.4. Covering What? Inequality, Invisible Vested Interests or Dehealthism

- The HLEG has completely failed to identify many of the constraints while recommending means and ways for universal health coverage. The health challenges in India are multi-layered and consequences of several complexes. Limited budgetary allocation from the central and state governments is only one of such constraints. Some other constraints, in the opinion of the present author, are: limited reach and scope of primary health care; medicalisation of all the financial resources; overlooking the basic health goods (BHGs); narrowing the reach and scope of public health; and state apathy, discrimination and mismanagement in the form of ‘dehealthism’.Identifying the continuities and gaps in existing health policy and planning in India, we can recognise that health gaps in India, to a great extent, is a consequence of cumulative wrongs at the level of policy prioritisation and planning. It is time to revisit the Alma Ata Declaration (1978)[34] which states that primary healthcare includes at least: (i) education concerning prevailing health problems and the methods of preventing and controlling them; (ii) promotion of food supply and proper nutrition; (iii) an adequate supply of safe water and basic sanitation; (iv) maternal and child health care, including family planning; (v) immunisation against the major infectious disease; (vi) prevention and control of locally endemic disease; (vii) appropriate treatment of common disease and injuries; and, (viii) provision of essential drugs. Out of these eight primary elements necessary for primary health care, the author considers unadulterated nutritious food, safe drinking water and sanitation as the ‘Basic Health Goods (BHGs)’. BHGs are basic in the sense that they are indispensable for human life and life is impossible without them. ‘Health for all’ is just an illusion without the comprehensive and sustainable availability of the BHGs to all individuals in any society and more particularly in developing societies like India.Many of the states in India have a lackadaisical approach towards making universal availability of primary health care and especially BHGs. The practise of denying primary health care and especially BHGs to the population or a part of it or even gradual withdrawal from it is denial of health chance and can conveniently be termed as ‘dehealthism’. Any group, community or state practising dehealthism can’t achieve the goal of health for all, no matter how much medicalisation it is promoting. It is important to note here that increasing medicalisation of the health structures has created several confusing and often overlapping discourses surrounding health, some of which are: primary health, holistic health, curative health, preventive health, promotive health, rehabilitive health, public health and community health. All these variants of health are meaningless if the group concerned is a victim of dehealthism. Dehealthism is closely related to the notion of medicalism. Medicalism promotes medicalisation in several senses: identifying new medical territories, increasing medical hegemony and gaze, pharmaceuticising the food and drinks etc, are some of the popular forms[35-36]. One of the consequences of medicalism, in India, is narrowing the field of ‘primary health care’. The notion of Primary Health Centre (the most important functional unit of health structure) in India is much narrower than what is prescribed in the Alma Ata declaration and says nothing specific about how to ensure delivery of BHGs. One further variant of medicalism in India is capturing all the budgetary allocations for health. Narrowing the scope or budget of public health[37] and exclusion of BHGs is also dehealthism. However, dehealthism is much more than it.Globalisation and market forces advocate dehealthism for promoting private interests through invisible networking. World Bank through its various publications and recommendations has argued for strengthening of private health care with the state shifting its role from being a provider to controller and regulator of services and its quality[37]. Often, global agencies dictate ‘terms of reference’ to the government for constitution of commissions which will work for promoting their interests. The adoption of managerial or techno-managerial approaches and strategies in policy and planning making serves the interests of various such invisible agencies[38].There is a new euphoria of marketisation of universal health coverage through policies like mediclaims and medicares for reimbursing the high medical care cost of individuals and groups. When such coverage is promoted as substitutes of primary health care provided by the state, it is dehealthism. Dehealthism reduces the territory of holistic health and perpetuates the conditions responsible for causation of disease and illness and in turn attracts medical interventions and medicalisation. Health inequality in India is also a result of the medical hegemony, invisible networking of vested interests (INVIs) and a vicious circle of medicalism and dehealthism.

8. Conclusions

- This paper suggests that a mere increase in budgetary allocation or privatisation or even public-private partnership is not a panacea for achieving the desired health goals or combating the deep malaise of health inequality. Health should be seen from a comprehensive perspective and should not be seen only from bio-medical perspective. Similarly, health coverage should also be seen from broad possible perspectives and not just from a narrow economic perspective. Availability and accessibility of basic health goods is the first and most fundamental step in this regard. The poor health outcome in many of the states of India is not just because of lack of health care institutions or medicines. Often, it is also caused by non-acceptance of the unhygienic and poor quality health care services. And further, large scale adulterations in food stuffs and very poor quality of the available drinking water make the health situation worst. While talking about universal health coverage, the government needs to take into consideration even such politico-administrative factors related to good health.It is very timely and relevant to advocate here for a broad based and inclusive public health policy and shifting away from the compartmentalised and segmented policy making. This comprehensive approach demands that along with focussing on medicine and curative health, all the basic health goods should also be made available and accessible to the most needful. The increasing medicalisation of health needs and especially the basic health goods should be stopped. Preventive and community health should be promoted as per the guidelines of Alma Ata declaration. The vested interest, involved at various levels should be identified and exposed and the unseen constraints should be properly addressed. And last but not the least, a better coordination among all the agencies be developed so that a better communication and reciprocation with the stake holders can be achieved. Health allocation must be increased (up to 5% of GDP) and a separate budget (2% of GDP) be allocated for providing BHGs and combating dehealthism in India.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML