Kimani Harun1, Mituko Shelmith2, Daniel Muia3

1Department of community health, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

2Department of Infection Control, Africa Infectious Diseases’ Village Clinics, Loitoktok, Kenya

3Department of Sociology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Kimani Harun, Department of community health, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Abstract

Despite recommendations for skilled reproductive health (RH) attendance, the contrary persists in sub-Saharan Africa. This study described the utilization of Unskilled Birth Attendants’ (UBA) services among women after adoption of the 2007 Kenyan RH policy. The services offered to women by Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) and factors associated with this persistent utilization of unskilled care were studied. A total of 328 Maasai women, 15 TBAs and 3 key informants participated in the study. Questionnaires, interviews and 28 days TBA activities’ register were used to collect data. The study area was selected purposively due to high utilization of UBAs while women were sampled randomly. Odds ratios, 95% C.I. and inferential statistics at p <0.05 compared those utilizing unskilled care with those who did not. Most women, 84.1% (276) utilized unskilled RH services at least once and 68% during delivery alone. TBAs offered RH services to 453 clients in 28days. Of those services, 36.4%, 35.3%, 25.2% and 3.1% were antenatal, delivery, postnatal and family planning respectively. Low education, advanced age and high parity were significantly associated to UBA utilization at p<0.05. The persistent utilization of UBAs services was attributed to availability of UBAs, ignorance of and poor access to skilled services. Skilled attendance can be improved by marketing the services, redirection of UBAs to offer safe services and improving RH infrastructure.

Keywords:

Unskilled Birth Attendants (UBAs), Reproductive Health (RH) Services, Maasai Women, Kenya

Cite this paper:

Kimani Harun, Mituko Shelmith, Daniel Muia, "Persistent Utilization of Unskilled Birth Attendants’ Services among Maasai Women in Kajiado County, Kenya", Public Health Research, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 213-220. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20120206.07.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Reproductive health (RH) is the ability to have a responsible, satisfying and safe sex life, capability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if, when and how often to do so and the right of men and women to access quality RH information and services[1]. Among other meetings, the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) 1994, the Millennium Summit and the Maputo conference put RH into global focus. The strategies proposed from these meetings to improve maternal and child health were to ensure all women access skilled RH care and information[2- 4]. In pursuit of good RH for its citizens, Kenya and its partners formulated the 2007 RH Policy. This study focused on the safe motherhood component whose policy actions were that: 1) All to access skilled RH services and information including contraception 2) Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) not be recognized as skilled providers. Their designated roles to be; assisting in birth preparedness, early referral of women, postnatal care and birth registration.3) Barriers that impede access to skilled health care are addressed 4) Health system capacity at all levels to be strengthened [5].Kenya adopted the RH policy in 2007, there being evidence of less maternal mortality and morbidity with skilled birth attendants[6]. However, there has been persistently low utilization of skilled birth attendance at 30.7% in Loitoktok District of Kajiado County and 31.7% in another similarly rural area, North Eastern Kenya[7] in 2008/2009. There is therefore, failure of RH interventions, including policy actions to improve proportion of skilled birth attendance in the division and other poor rural settings. In view of this, the study set out to generate current information to confirm and describe the persistence and suggest ways to safely utilize unskilled attendants in RH.

1.2. Methods

1.2.1. Research Questions

1) What is the proportion of women utilizing unskilled birth attendants’ (UBA) services?2) Which RH services are currently being offered by TBAs?3) Which factors are associated with persistent utilization of UBAs?4) Which activities can UBAs carry out to improve RH in Mbirikani division?

1.2.2. Sampling Techniques

The study took place in Mbirikani Division of Loitoktok district of Kajiado county, Kenya, inhabited mainly by the Maasai. The area was purposively sampled because of high incidence of unskilled birth attendance. The women were sampled from clusters along sub-location boundaries; Imbirikani, Oltiasika, Karei and Emukutan, with population ratio 3:3:3:1. A woman was interviewed from each randomly sampled household in the sub-locations. Inclusion criteria* Aged 15 to 49 years * Given birth after 2007. * Lived in Mbirikani division for at least 9 months. TBAs were purposively sampled for being known to be attending to births traditionally. Inclusion criteria* Registered with the government of Kenya* Lived in Mbirikani Division for at least 5 yearsAll the 15 TBAs who met the criteria were selected.The Key informants were purposively sampled and had to be conversant with RH practices in the communityInclusion Criteria* From the majority tribe; Maasai.* Having resided in study area for at least 20 years.Exclusion criteria for all participants* Not willing to respond unconditionally. * Unable to consent

1.2.3. Data Collection

Interviewer administered questionnaires were used to collect data on the RH services the Maasai women utilized including FP, ANC, delivery and PNC. Interviewer administered questionnaires for TBAs collected data on TBAs’ workload, suggestions on how to safely utilize UBAs to improve RH and on any comments they wished to give concerning the services they offered. TBAs’ activities register was used to keep journal of TBAs’ activities over 28 days, noting number of women seen by each TBA and the services offered to each woman. Interview guide for key informants collected qualitative data on reasons women utilized TBA services for FP, during ANC, delivery and PNC periods, cultural practices for those services, and their individual suggestions on how to safely utilize UBAs to improve RH. Secondary data: the 2007 RH policy document, district hospital data, national documents, publications, journals, books, reports and the internet sources were used in reviewing literature. A pretest of tools was done in Kimana Division, with majority of habitants being rural Maasai people. It helped to revise research instruments, harmonize and map out main study logistics.

1.2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data was summarized, counted, coded and entered into SPSS version 18 and Excel where it was analysed and interpreted. Descriptive statistics were generated from quantitative data. Qualitative data was analysed for in-depth inference. Data was presented in tables, charts and prose.

1.2.5. Ethical Considerations

Authorization to carry out the study was sought and obtained from Kenyatta University Graduate School, National Council for Science and Technology and Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The responses were kept confidential.

2. Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics, odds ratios with 95% C.I. compared the utilization between groups of women, while the chi square statistics with significance at p value <0.05 showed the level of significance of association of women factors to outcome (utilization of UBA services). Multiple logistic regressions were further used to control for confounders to the utilization. Linear regression was applied to continuous data to determine strength and nature of correlation of TBA factors to the utilization of TBA services. The results describe the proportion of utilization of UBAs among Maasai women, services offered by TBAs and suggestions to utilize UBAs safely.

2.1. Women

The women were aged 15 to 49 years, mean of 31.67 years. Most of the respondents, 41.8%, were 25 to 34years of age and 21.3% of the women had more than 6 children. The monthly income estimate and the number of animals owned were recorded. The level of income was classified into three; low (Ksh 10001 + >10 animals). Many women, 71.6% had low income while only 4% had high income. The majority of the respondents, 54.9%, lived within 30 minutes walk to a health facility while more than 25% of the respondents had to walk for more than one hour to reach the nearest facility. The level of education achieved by the women was recorded as 59% had no formal education and only 2% had tertiary education. Among the women interviewed, 79.9% were married, 14% widowed and 6.1% single. Radio was the most commonly accessed media, by 78% of women followed by public fora (barazas, peer meetings) at 16%. As many women accessed television as those who did the newspapers at 3%.

2.2. TBAs

Tbas were aged 48-70yrs, mean 60yrs, had 5-40 years of TBAs’ experience, mean 22yrs. TBA skills were acquired as follows; apprenticeship 53%, seminars 27%, self acquired 20%. No TBA had any formal education. A total of 33.3% of the TBA respondents practiced female genital mutilation as well.

2.3. Utilization of Unskilled Birth Attendants’ Services

The data in table 1 was summarized from women’s responses when asked whose services they utilized after 2007 for their latest ANC, delivery, PNC and FP needs. Utilization of unskilled attendants was at 49% ANC, 68% delivery, 53% PNC and 3% FP as shown in table 1. Some women utilized both skilled and unskilled services at 16% and 13% for ANC and PNC respectively. Among the UBAs, TBAs were utilized most during antenatal and delivery, while relatives were utilized more for postnatal care by 84 women (25.6%). Other UBAs; neighbours and selves also offered services to a few women.| Table 1. Proportion of women utilizing unskilled and skilled attendants’ services |

| | Service Category | Unskilled | Both | Skilled | | TBA | Relatives | | Antenatal | 95 (29%) | 13 (4%) | 54 (16%) | 166 (51%) | | Delivery | 194 (59%) | 23 (7%) | 6 (2%) | 105 (32%) | | Postnatal | 46 (14%) | 84 (26%) | 42 (13%) | 156 (47%) | | F/Planning | 0 | 3 (2%) -self | 0 | 160 (98%) |

|

|

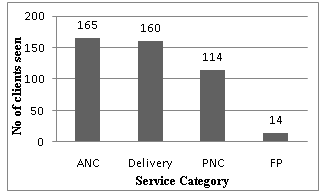

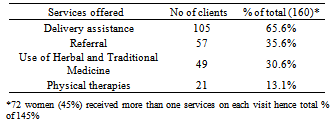

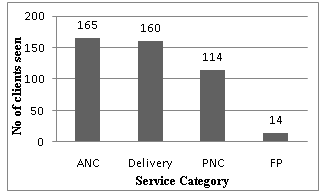

In the year 2009, a study done in Nyandarua, Kenya reported 51.8% UBA deliveries. Unlike this study however, only 1.5% were delivered by TBAs. The rest, 50.3% were by other UBAs; neighbours and/or relatives and self[8]. What this and other studies imply is that other UBAs are still offering RH services especially PNC. The 28 day journal of TBA activities shown in figure 1 below documents further that UBAs were still providing RH services to women.  | Figure 1. No of clients seen by TBAs per category of service. N = 453 |

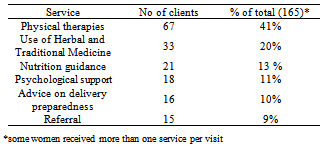

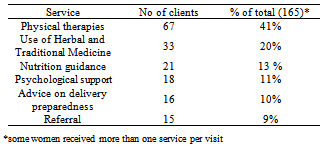

The TBAs saw a total of 453 clients; hence a TBA’s workload ratio per day is 1:1.1.The study documented that 276 (84.1%) women had utilized the services of UBA at least once after 2007 while 52 (15.9%) had not utilized the services at all. Utilization of unskilled ANC services was at 49%. Many studies document utilization of skilled and not unskilled ANC services. The national utilization of skilled ANC services is 92% while the district utilization is at 81.5%[9]. This could be accounted for by the fact that some women utilize both UBA and SBA services even during the same pregnancy, by up to 16% in this study. During ANC, 67 (41.1%), received physical therapies from TBAs. These included massage, abdominal palpation, external cephalic version and application of warm packs. Traditional medicine composed of animal fats or other animal products mixed with herbs. The cultural practices during this period as stated by key informants include: Use of herbs and traditional medicines in massage and palpation and to treat RH infections, modifying woman’s appetite, emetics if undesired foods are eaten, and inducing diuresis in women with edema. Nutrition guidance included the advice that at 3 to 4 months gestation the Maasai women should eat anything except milk and after the sixth month they should eat one non fatty meal per day e.g thick porridge (to retard growth of baby for easy delivery). Table 2 below shows the unskilled antenatal services offered to women during the study period. The number of women referred to SBAs during ANC was only 15 (9%). Of the women who were referred to the hospital, 66.7% were said to have had serious problems such as antepartum hemorrhage, loss of fetal movements or the mother being too sick like being very hot or fainting.Table 2. ANC services provided by TBAs

|

| |

|

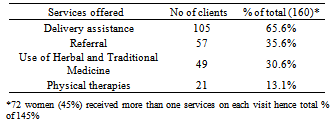

In 2003, the Family Care International (FCI) reported similar findings where TBAs offered physical therapies, herbs and helping with delivery preparedness in Nyanza[ 10]. Lech and Mngadi also reported that unskilled attendants offered herbs and nutritional guidance in Swaziland[11]. This study documents utilization of unskilled delivery services at 68%. Key informants explained that high utilization of UBAs was because many women feared invasive examinations such as digital and speculum examinations and also feared being sent for operations which, from their point of view, had bad outcomes for their babies. In most developing countries Kenya included, unskilled delivery services are utilized more than skilled. For instance, Kenya’s national unskilled services’ utilization is at 58%, Haiti at 74% and Ethiopia at 94%. Utilization of unskilled delivery services is more in some regions (especially poor rural setups) such as North Eastern Kenya at 68.3% and Loitoktok district at 69.3%[9,12]. This comparison shows regional disparities in RH status. During the study period, TBAs’ records showed that they provided the delivery services to the women as shown in the table below. Majority of the women, 65.6% (105) were assisted to deliver. There were 2 stillbirths and 1 premature infant who died within minutes of delivery. The women leader explained that, ‘women still fear to deliver in the hospitals because of invasive exams (digital and speculum vaginal exams) which are degrading and very uncomfortable. She noted further that often, when one goes to the hospital, they are sent for operations (caesarean section) and that at home unlike in the hospital, there are no men at the delivery site.’ She added, ‘Also the time matters, it is difficult to go to hospital at night with all the animals roaming around.’ However, the male informant pointed out that hospital deliveries were increasing due to improved ambulance service provided by the local nongovernmental health facility.Table 3. Delivery Services offered by TBAs

|

| |

|

Herbs (and traditional medicines such as goat fat) and physical therapies (massage, palpation, external rotation of the fetus and application of warm packs) were used in complications such as bleeding, prolonged or obstructed labor. More women were referred during labour, 35.6% (57) than during the ANC period. Culture was practiced where women were given goat fat, taken orally, to make the baby slippery so as to hasten delivery; during difficult labor, a thick handle of a traditional knife or bottle was said to be pushed down a woman’s throat to induce vomiting so that the retching gives her power to push the baby. Warren and Mwangi reported that TBAs offered delivery assistance to women in western Kenya while in 2003, the FCI reported that they offered assistance, physical therapies and herbs during delivery in Nyanza[13,14]. Even though more women were referred, 35.6% during delivery period, the informants reported that many TBAs waited too long. ‘The fact that they are paid by the community members for each delivery just makes it more difficult for them to refer mothers,’ said the male informant. Again, policy actions should endevor to facilitate TBAs to be able to refer all mothers to health facilities. | Table 4. Postnatal Services offered by TBAs |

| | Services offered | No of clients | % of total (114) | | Nutrition guidance | 38 | 33.3% | | Total Home Care | 37 | 32.5% | | Counselling | 22 | 19.3% | | Referral | 14 | 12.3% | | Use of Herbal and Traditional Medicine | 3 | 2.6% |

|

|

This study showed that 52.4% of women utilized UBA postnatal services at least once. Relatives provided most of the unskilled postnatal services at 26% of total. This was supported by all the key informants’ recount that PNC services were mainly being provided by mother-in-laws. During the postnatal period, TBAs saw 114 women and offered the services listed in table 4 below. Nutrition guidance for mother and baby was provided to about 33% of the clients. During this period, mothers were encouraged to eat plenty of any foods and to breastfeed.Home care services offered to mothers who had delivered included maintaining hygiene and care of the newborn. This would be done for 2-3months when the mother’s job would be to eat and rest. Postnatal mothers were counselled on hygiene, baby care and rest. Use of herbs and traditional medicine was offered to 2.6 % of clients.Supportive services that could be reinforced include good feeding, home care and counselling, services that are allowed by the policy document and are supported by studies in India[15]. Culture also reflected in PNC where the younger woman informant explained, ‘Ash and/or saliva is put (by relatives or TBAs) on the raw cord to aid healing.’ The older woman informant added, ‘cute and big babies are hidden from women of certain families so they do not look at the baby badly, such babies are not allowed to leave the house for 1-2 months after delivery.’ It is clear that mothers and UBAs all need to have information about such cultural practices, which may put children at risk of infections and women at risk of complications like venous thrombosis or osteoporosis for instance, in the 2-3 months of a woman is inactive. At the same time, the tradition of not allowing the newborn out of the house delays the seeking of skilled PNC, child immunization and growth monitoring. Some women, 13% utilized both skilled and unskilled postnatal services. However, the informants said that skilled postnatal services’ utilization was late and mainly aimed to monitor the babies. The lack of total or prompt seeking of skilled PNC care could increase mothers’ and neonates’ morbidity and mortality as noted by the 2008-2009 KDHS, that ‘a large proportion of maternal and neonatal deaths occur during the first 48 hours after delivery’. A study by Sines noted that essential postnatal care services are often absent and that where available, often lack essential elements of care required for the optimum health of the mother and her newborn. The same study suggests training TBAs on PNC so they can offer good care to those women they capture[16]. However, in Mbirikani, most Maasai women utilizing UBA services for PNC (60%) get the services from relatives so training TBAs would not have the desired impact and even so, most TBAs are illiterate (100% in this study) and so hard to properly educate. This as explained by the key informants, focuses on nutrition and rest for mother and baby but lacks some essential services such as proper umbilical cord care, perineal hygiene and breast care for the mother. In the Mbirikani Division, 98% of the Maasai women using FP utilized skilled providers, a level influenced by culture positively and negatively. This was 48% of total number of women sampled. The culture, as explained by the key informant is that among the Maasai (of the division), a person seeking FP services was seen as being promiscuous. This then led many women looking to plan their families to seek skilled services as they may not be stigmatized by the skilled workers. On the other hand, this belief may cause some women not to seek the service at all. Looking at the TBA registers, one can see that TBAs offered FP services (advice on natural FP and referral) to only 14 (3.1%) women. However, many women receiving advice on natural FP may not consider this as FP service per se and so such utilization might not be captured in the study. Skilled family planning utilization usage in Kenya is at 46% going by the 2008/2009 KDHS statistics. A study done by Owino documented similarly low levels of unskilled FP utilization at 15.6% in Nyanza[17].

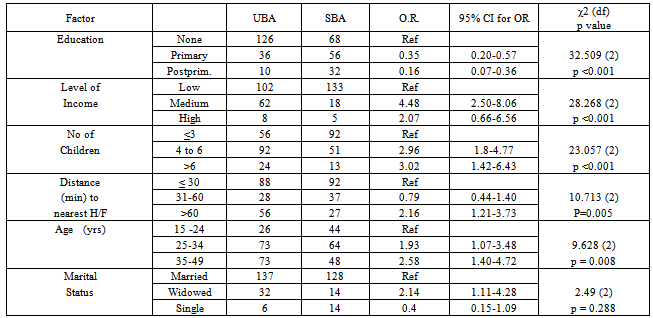

2.4. Factors that Were Significantly Associated to Utilization of UBAs’ Services

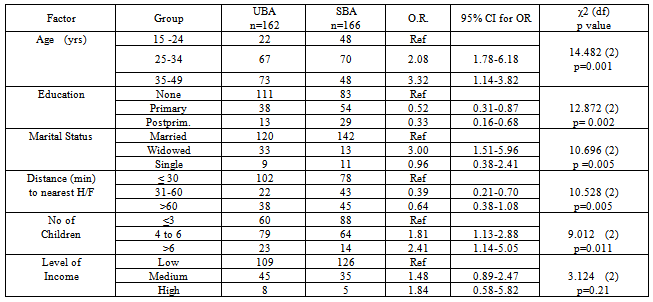

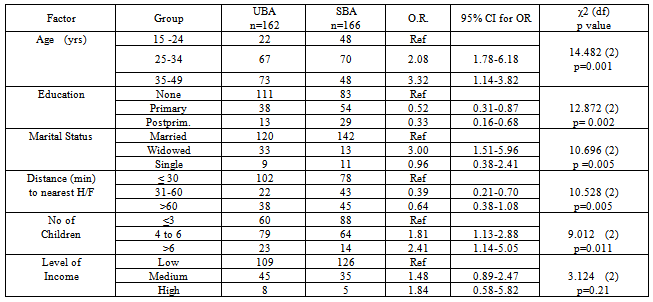

The association of age, number of children, education level, distance to health facility, level of income and marital status to unskilled attendance utilization was studied. All except level of income were significantly associated to UBA antenatal services’ utilization with P < 0.05. Odds ratios for age groups 2-3 95% CI 1-6 while for education levels 0.3-0.5, 95% CI 0.16 -0.8. Education and age were significant when controlled for confounders at p<0.002 and 0.004 respectively. The significance of education was echoed by Babalola and Fatusi where education was found to predict utilization of ANC, delivery and postnatal services[18]. Significance of distance on RH services’ utilization was supported by Mwaniki et al[19].Table 5. Women factors Vs Antenatal Services’ Utilization

|

| |

|

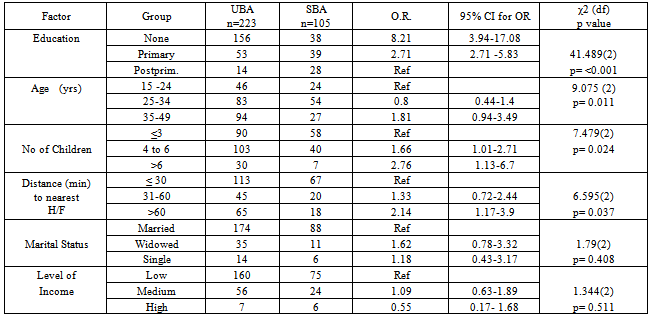

Table 6. Women factors Vs delivery services’ utilization

|

| |

|

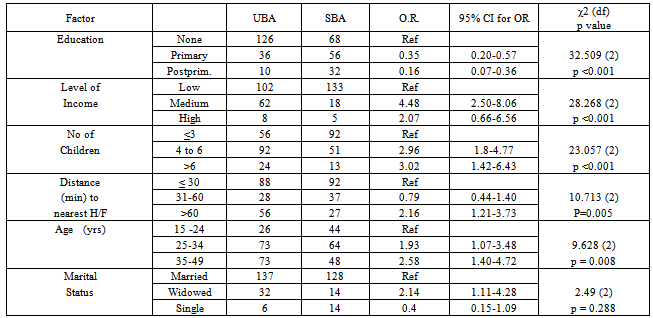

Table 7. Women factors Vs postnatal services’ utilization

|

| |

|

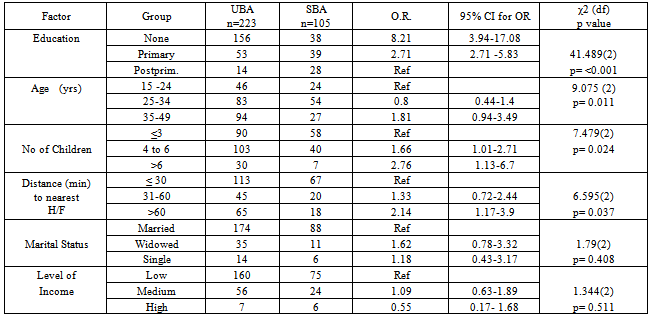

Age, number of children, education level and distance to health facility, were significantly associated to UBA delivery services’ utilization with P <0.05. Odds ratios for education levels 2-8, 95% CI 3 -17. Education remained significant when controlled for confounders at p< 0.001. These agree with the findings of Gabrysch and Campbell where educational status, age and parity among other factors were significantly associated with choice of place of delivery although that study found marital status to be significant unlike this one[20]. There are also the dangers of encountering wild animals that pry the division especially at night that contributed to mothers seeking UBA services during delivery. Cases of elephant, buffalo and hippo attacks were not uncommon. This really confirms the sentiments expressed by one of the TBAs interviewed by Anyangu-Amu that insecurity caused the women to find the nearest service which was the UBAs for RH care[21].UBA postnatal services’ utilization was significantly associated to all but marital status, P <0.05. Income and level of education remained significant even when controlled for confounders at p <0.001. Indonesian health literature review by Titaley et al supported that education, income and distance affected utilization of PNC services[22].

2.5. Suggested Utilization of UBAs

Women, TBAs and key informants were asked how UBAs can safely participate in RH. Many women, 25%, said TBAs should continue offering herbs and referring women to hospitals. The 22% of women wanted TBAs to be allowed to distribute supplies like mosquito nets and common medicines like iron and folate tablets during ANC period. Formal training of TBAs on safe RH services was suggested by 19% of women while 18% said screening and treating TBAs of illnesses regularly would improve safe RH services. Other women, 11%, said TBAs could be attached to hospitals to gain experience from SBAs. Other suggestions on safe utilization of UBAs by women included the following: government to allow both SBAs and UBAs to practice, UBAs to help with household chores, newborn care, and to encourage women during delivery.When asked about this, the older female informant said, ‘TBAs should be trained and facilitated with delivery kits,’ and the younger said, ‘the community should be educated on skilled services for them to accept them,’ while the male said that their referral role should be encouraged e.g. by giving them means to communicate to the hospital in case of need or emergencies and recommended that another health facility with capacity to handle RH matters be set up in the division and that TBAs be trained to offer safe RH services.From reviewed literature, it has already been established that training TBAs does not bring positive change in RH outcomes and therefore such suggestions would be rejected[23]. Therefore, the suggestions that should be looked into further include:Educate women and men on the benefits of skilled services to foster utilization1). UBAs to support mothers psychologically during the phases of reproduction2). Delegating house chores to UBAs to help rest the woman3). UBAs to distribute supplies from the health facilities such as mosquito nets4). UBAs to assist women prepare for delivery 5). Support their role to refer all clients to SBAs. The last five suggestions are also pointed out in studies by Mwangi & Warren in western Kenya and by Dadhich in India. Rodgers found it useful to integrate TBAs in health institutions in Honduras[13, 15 and 24].

3. Summary, Conclusion and Recommendations and Further Research

3.1. Summary

In summary, the following were found, through quantitative and qualitative analysis to be among the reasons why the Maasai women are persistently utilizing UBAs:1) Low literacy levels 2) Advanced age or the woman >35years3) High parity >6children4) Ignorance of and poor access to skilled services5) Conducive culture; need for herbal medicines and expectations from family/community to utilize TBAs6) Availability and ‘trust’ in UBAs by women even at night when wild animals are roaming the villages

3.2. Conclusions

The results demonstrate, contrary to the policy objectives and MDGs that majority of Maasai women were persisting in utilizing unskilled birth attendants. The findings showed that other UBAs (other than TBAs); relatives, self, neighbours also provided RH services and as such, should not be excluded from RH policies. They continued to utilize unskilled services largely because they believe UBA services are good for them. The study brought out suggestions to utilize UBAs safely such as to include them in RH education and promotion. The utilization on UBA services in Mbirikani division and in similar marginalized areas being as high as it is, public health professionals need to drive change that will ensure a reversal of the poor statistics on RH.

3.3. Recommendations

Recommendations brought forth from the findings of this study are: 1) Active education of the community on the benefits of skilled services should be intensified in order to create demand for the skilled services. Sensitization on policy actions to gain grass-root support will improve adherence to policies and increase utilization of skilled services. 2) Campaign against cultural practices that are risky such as insistence on seeking UBA services, denial of foods in the second and third trimesters and unclean handling of the umbilical cord.3) Liaison with the wild life management should be done to ensure the wild animals that are posing danger to people are contained to ensure women are able to safely access health services at all times.4) Break barriers to utilization of skilled services by improving women’s education level, access to skilled services and reducing parity through family planning.5) Research into proposed and ongoing interventions in RH should be encouraged and supported so as to provide objective guidance to strategies and also to provide information for monitoring and evaluation.

3.4. Further Research

Research should be carried out into activities that UBAs can carry out to improve RH in order to determine which ones are safe for adoption. Similar studies need to be duplicated in other hard to reach, resource poor and socio-culturally challenged settings so as to come up with more supporting evidence.

References

| [1] | Online available:http://www.who.int/topics/reproductive_health/en/. |

| [2] | Online available: http://www.iisd.ca/cairo.html. |

| [3] | Bernstein, S., Population, Reproductive health and the Millennium Development Goals. Communications Development Inc, Washington D.C, 2005. |

| [4] | African Union, Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, AU, 2003. |

| [5] | Buigutt, K. (ed.), National Reproductive Health Policy: Enhancing Reproductive Health Status for all Kenyans. Government of Kenya press, Nairobi, Kenya, 2007. |

| [6] | Canavan, A., ‘Review of Global Literature on Maternal Health Interventions and Outcomes Related to Skilled Birth Attendance’, KIT, Amsterdam, Royal Institute of medicine, 2009. |

| [7] | Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS)[Kenya], Ministry of Health Kenya, Kenya Medical Research Institute, National Council for Population Development, ORC Macro and Centers for Disease Control, Kenya Demographic Health Survey 2008-2009. KNBS and ORC Macro, Calverton Maryland, 2010. |

| [8] | Wanjira. C, M. Mwangi, E. Mathenge, G. Mbugua and Z. Ng'ang'a, ‘Delivery Practices and Associated Factors among Mothers Seeking Child Welfare Services in Selected Health Facilities in Nyandarua South District, Kenya’, BMC Public Health, volume 11 issue 360, 2011. |

| [9] | Republic of Kenya, District Development Plan 2008-2012, Loitokitok district, Nairobi, Kenya: Government press, 2008. |

| [10] | Online Available:http://www.familycareintl.org/UserFiles/File/Anglo_Toolkit_June2008.pdf. |

| [11] | M. Lech, and P. Mngadi, ‘Swaziland's Traditional Birth Attendants Survey’, African Journal of Reproductive Health, volume 9, No. 3, December, 2005, pp. 137-147. |

| [12] | Online Available:http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs348/en/index.html. |

| [13] | Online Available:http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/SafeMom_FinalReport.pdf. |

| [14] | Online Available: http://www.familycareintl.org/. |

| [15] | J.P. Dadhich, ‘The traditional birth attendants - can we do without them?’, Journal of Neonatology, Volume. 23, No. 3, 2009. |

| [16] | Online Available:http://www.prb.org/pdf07/snl_pncbrieffinal.pdf, January. |

| [17] | B. Owino, ‘The Use of maternal health care services: Socio-economic and demographic factors – Nyanza, Kenya’, Demographic Studies, volume 21, 2001, pp. 81-122. |

| [18] | Babalola, Sand A. Fatusi, (2009). ‘Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria - looking beyond individual and household factors’, BMC Pregnancy and childbirth, volume 9:43, 2009. |

| [19] | Mwaniki, P., Kabiru, W., and Mbugua, G., ‘Utilization of maternity services by mothers seeking child welfare services in Mbeere district, Eastern province, Kenya’, East African Medical Journal, volume 79, No 4, 2002. |

| [20] | Gabrysch, S. and Campbell, M., ‘Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use’, BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, Volume 9:34, Aug 11. 2009 |

| [21] | Online Available:http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=52274 |

| [22] | Online Available:http://jech.bmj.com/content/early/2009/05/03/jech.2008.081604.full.pdf. |

| [23] | Online Available:http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/SafeMom_TBA.pdf, 2003. |

| [24] | Rodgers, K., Little, M. and Nelson, S., ‘Outcomes of training traditional birth attendants in rural Honduras: comparison with a control group’, North Carolina: Chapel Hill, Journal of health and population in developing countries, 2004. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML