-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2012; 2(6): 197-203

doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20120206.04

Comparative Study of Compliance Between Hospital and Primary Care Diabetic Patients

Fawzy Sharaf, Farid Midhet, Abdulrahman Al-Mohaimeed

Family and Community Medicine Department, College of Medicine, Qassim University Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Fawzy Sharaf, Family and Community Medicine Department, College of Medicine, Qassim University Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

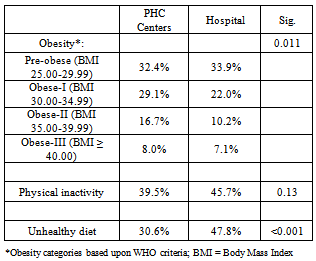

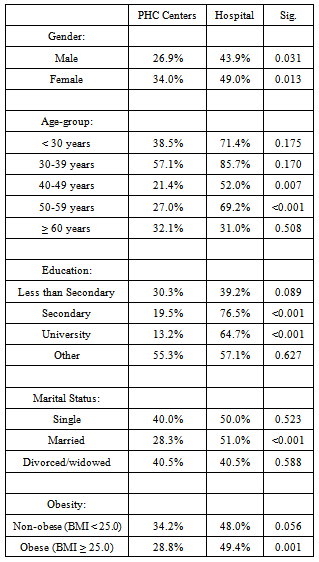

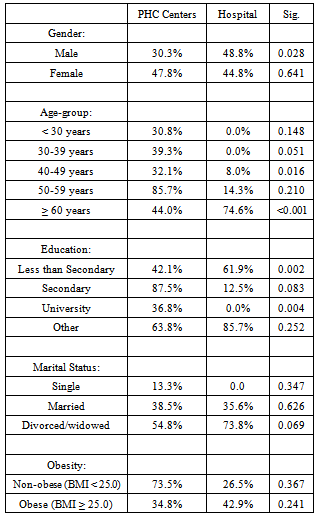

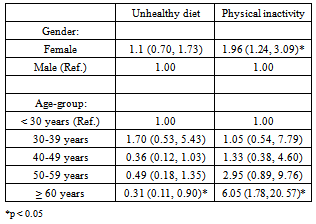

Modern day chronic diseases such as diabetes are related with the lifestyle, especially unhealthy diet and physical inactivity. This study aims to determine the level of compliance of diabetic patients with their doctors’ advice about diet and physical activity, comparing ambulatory patients with those who were recently hospitalized. We developed a combined database of the two studies. Both studies were cross-sectional studies using systematic random sampling comprising patients of T2DM, and including the following variables: health facility used by the patient; age; gender; marital status; education; whether the patient received health education in the past; patient’s weight and height and presence of other diseases; family history of diabetes; current smoking; dietary habits; and exercise. We used the SPSS data reduction method factor analysis to summarize the data on these two dimensions (diet and exercise) into a single summary variable each. The total number of diabetic patients included in this study was 442. Prevalence of smoking was 7.2% (6.3% among PHC patients and 9.4% among hospital patients; p=0.16). A little more than one third of the PHC patients and nearly three fourth of hospital patients had hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD) or both (p<0.001). Similarly, a significantly greater proportion of the hospital patients had a family history of diabetes (p<0.001). Obesity was significantly higher among the PHC patients (p=0.011). The prevalence of unhealthy diet was significantly higher among hospital patients (p<0.001). Percentage of patients having unhealthy diet was significantly higher in among hospital patients in both sexes (p < 0.05), and in the 40-59 age-group; having secondary and higher level education, the prevalence of unhealthy diet was several times higher among hospital patients (p < 0.001); same was true among married patients, where the percentage of unhealthy diet was almost twice among hospital patients (p < 0.001). Finally, the prevalence of unhealthy diet was significantly higher among non-obese hospital patients than the non-obese PHC patients (p = 0.001). The prevalence of physical inactivity among male hospital patients was significantly higher than the male PHC patients (p=0.028). In the age 60 years and above, physical inactivity was significantly higher among hospital patients (p < 0.001). Similarly, among patients having less than secondary school education, physical inactivity was significantly higher among hospital patients (p = 0.002). Prevalence of unhealthy diet is significantly higher among hospital patients. We conclude that health care providers in Saudi Arabia should put greater emphasis on health education about diet and exercise. with T2DM.

Keywords: Compliance, Diabetes, Diet, Physical Activity, Saudi Arabia

Cite this paper: Fawzy Sharaf, Farid Midhet, Abdulrahman Al-Mohaimeed, "Comparative Study of Compliance Between Hospital and Primary Care Diabetic Patients", Public Health Research, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 197-203. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20120206.04.

1. Introduction

- Modern day chronic diseases such as diabetes are related with the lifestyle. Unhealthy diet and physical inactivity are the most important risk factors for diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), both for their causation and for their prognosis. Failure to follow a strict diet and exercise regimen, in addition to prescribed medication, is a leading cause of complications among patients of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). . Studies have shown that in order to improve metabolism and reduce the risk of late complications of T2DM, permanent changes are needed[1] . For instance; exercise in groups (exercise period rangingfrom 8 weeks to 12 month) has been shown to lower HbA1c by approximately 0.6 percentage points[2]. Similar results have been shown with diet control[3]. Diet, prescription anti hyperglycemic drugs and exercise routines are equally important contributors to treatment of T2DM. Physical activity and sports are one of the main contributors to both prevention and management of diabetes[4]. Although not in all patients, patient education programs alone have improved glycaemic control in diabetics[5]. In diabetes management programs, health care professionals plan the process but only the patients can perform this complex medical regimen; therefore, compliance is the key factor in diabetes management. Patient education may also result in increasing treatment participation and independence in daily activities, reducing complications and costs[6].Saudi Arabia has one of the highest prevalence of T2DM in the world. Nearly one fourth of adult population > 30 years is suffering from T2DM[7]. Previous studies have found that diabetic patients in Saudi Arabia do not take precautions with regard to diet and exercise[8,9], even though this advice is given routinely by their physicians. Compliance is defined as the extent of adherence of the patient to medical advice. The quality of the compliance depends entirely on patient cooperation and his/her understanding of disease condition and its management[10]. A study in Karachi, Pakistan assessed the impact of targeted patient education on the level of compliance by grouping subjects in quartiles according to percentage of dietary suggestion followed. They found a reasonable impact at the follow-up visit, whereby small proportion (9.7%) had poor compliance, 33.3% had fair compliance, 37.5% had good compliance and 19.4% had very good compliance[11]. The main reason poor compliance was that following a meal plan was difficult in a family setting[12].Since T2DM is a lifelong disease, it requires self-management by patients with regard to medication, blood testing, diet and exercise. A cross-sectional study in rural Egypt found that adherence to diabetes self-management was only 42% of patients. While there were no gender differences in compliance, older patients with longer duration of disease were less likely to comply with dietary instructions and had poorer glycemic control. There was a statistically significant association between education and compliance with dietary management of diabetes; one quarter (25.8%) of fhe illiterates patients were not compliant with dietary management. Recently detected diabetics (less than one year) were more compliant with dietary management of diabetes. However, with increasing time elapsed, they became less compliant. Concerning adherence to the prescribed diet, 41.7%, 38.8% and 19.4% were more frequent, less frequent and non-compliant with dietary management of diabetes respectively[13]. Given the complex nature of diabetes, it is understandable that most adults will sometimes suffer lapses in adherence to exercise, which could become an important contributing factor to therapeutic failure, ultimately interfering with the effectiveness of diabetes management. As T2DM mostly affects middle-aged and older adults, understanding the challenges to exercise adherence may be all the more important given recent evidence that participation in and adherence to exercise are relatively low in middle-age and older adults[14]. Many studies have found that diabetics are less compliant to instructions with regard to exercise than any other aspect of self-management[15]..A study in urban Cairo, Egypt, found good compliance rates for all therapeutic tasks except smoking and exercise among highly educated diabetic patients. In this study, males had a significantly higher total compliance score (16.6%) than females (6.3%); compliance was also higher among those suffering from co-morbidities (25.5%) and among those who had better knowledge about the disease (36%)[16]. The overall impression from previously conducted studies on compliance to diet and exercise among diabetic patients is that the clinicians and health educators face an uphill task in convincing their patients about the importance of their instructions. In the present study, we try to determine the level of compliance of diabetic patients with their doctors’ advice about diet and physical activity, comparing ambulatory patients with those who were recently hospitalized due to some complication of their disease. We also identify the patterns of such compliance among male and female and young and old patients after controlling for the effects of education and disease stage.The objective of our study is to estimate the effects of age, gender, education, etc. on smoking, diet and physical activity among diabetic patients.

2. Methods

- We used the raw data from two separate studies conducted in Qassim region of Saudi Arabia during 2010 and 2011, respectively. The first study was a comparison of ambulatory type 2 diabetic patients, who were being treated in primary health care (PHC) centers, with healthy controls to establish the differences in their dietary patterns and physical activity. The second study elicited similar information from diabetic patients who were hospitalized for the treatment of complications during the past six months. These patients were interviewed during their first follow-up visit to the secondary hospital after discharge. Both were cross-sectional studies using systematic random sampling methods, whereby the samples are considered to be representative of the population utilizing the PHC centers and the hospital, respectively. In the first study, every 5th patient of type 2 diabetes reporting to one of six participating PHC centers was interviewed. In the second study, all patients of type 2 diabetes who were discharged from King Saud Hospital in Unayzah, Qassim, during last three months and were visiting the hospital for follow-up were interviewed. The two studies had separate objectives and designs. However, the common element was the questionnaire (adopted from the World Health Organization[WHO]) eliciting information on smoking, diet and physical activity. In both studies, the dichotomous variables for unhealthy diet and physical inactivity were constructed through factor analysis of the data collected through the WHO questionnaire, which was similar in the two groups. We reduced the data from 16 variables for unhealthy diet and 9 variables for physical inactivity into regression factors (through the data reduction method factor analysis of SPSS v. 19.0); we then designated all values below zero (which corresponded with the mean) as ‘good’ and all values above zero as ‘bad’. The resulting summary variables were coded as 1 for unacceptable levels of unhealthy diet or physical inactivity and 0 for acceptable levels of unhealthy diet and physical inactivity. Information on demographic characteristics (age, gender, education and marital status), anthropometric measurements (height and weight), and family history of diabetes was similarly collected in both studies. Therefore, it was possible to extract these data and combine them into a single study. We differentiated between the two categories of patients (those being treated at PHC centers and those recently admitted to hospitals), to see the differences in their diet and exercise routines. We developed a combined database of the two studies, comprising patients of type 2 diabetes, and including the following variables: health facility used by the patient (PHC or hospital); age; gender; marital status; education; whether the patient received health education in the past; patient’s weight and height and presence of other diseases (hypertension, coronary artery disease or both); family history of diabetes (mother, father, both parents, other relatives); current smoking (yes, no); dietary habits (extracted from a validated 24-hour dietary recall questionnaire and summarized into healthy/unhealthy categories, as described above); and exercise (conscious efforts to do regular exercise regardless of intensity, extracted from the STEPS questionnaire of the WHO and summarized into yes/no categories). Data were analyzed using SPSS version 19.0. We generated frequency tables of all variables and conducted cross-tabulation between origin (PHC or hospital) and the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and smoking, diet and exercise. We used Chi-square test to estimate the statistical significance of association between the cross-tabulated variables. Finally, we used logistic regression analysis to estimate the effects of age and gender on diet and physical activity after controlling for origin and education.

3. Results

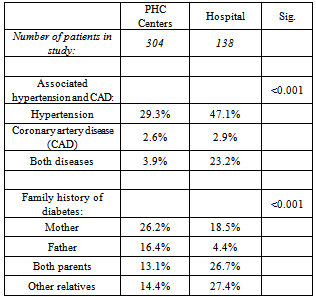

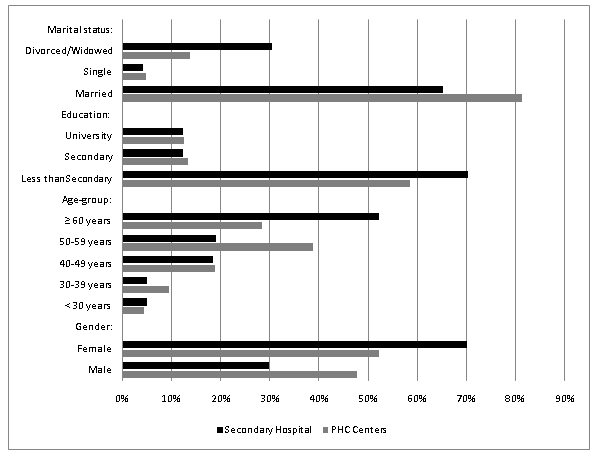

- The total number of diabetic patients included in this study ps 442 (304 from the PHC centers and 138 from the hospital). As expected, the hospital patients are older than the PHC centers’ patients. A majority of the hospital patients (70%) are female; they are also more likely to be widowed or divorced and they are slightly more likely to have lower education than the PHC centers’ patients (Figure 1).Prevalence of smoking was 7.2% (6.3% among PHC patients and 9.4% among hospital patients; p=0.16). Since the number of smokers was small (n=32), we did not pursue any further to identify the determinants of smoking in our sample. A little more than one third of the PHC patients and nearly three fourth of hospital patients have hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD) or both (p<0.001). Similarly, a significantly greater proportion of the hospital patients have a family history of diabetes (mother, father or other relatives), compared to the PHC patients (p<0.001) (Table 1).

| Figure 1. Demographic characteristics of patients |

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The reason for of noncompliance among diabetics is multi-factorial we considered four risk factors that can deteriorate the illness among diabetic patients. These are smoking, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and obesity. Evidence from global studies indicate these factors indeed are responsible not only for the causation of diabetes but also for several of the complications related with type 2 diabetes. Smoking increases blood glucose concentration and may increase insulin resistance[17,18], and the smokers also tend to have higher blood concentrations of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) than do the non-smokers[19,20]. A randomized controlled trial found that an intensive diet intervention soon after diagnosis can improve glycemic control, although addition of a physical activity intervention conferred no additional benefit[21]. However, the American Diabetes Association recommends that exercise, including resistance training, aerobic exercises, etc. help reduce the risk of complications among diabetic patients, reduce the risk of frank diabetes among impaired glucose tolerance patients and generally reduces the risk of CAD among diabetics[22]. In our study there is no difference in the prevalence of pre-obesity in the two groups of patients; obesity is significantly higher among the PHC patients. There is no difference between the two groups with regard to prevalence of physical inactivity; however, prevalence of unhealthy diet is significantly higher among hospital patients. In our study the prevalence of unhealthy diet among PHC and hospital patient, those having unhealthy diet was significantly higher among hospital patients in both sexes, this can be explained by the good doctor-patient relationship which is better in PHC than hospitals, because the PHC is the first line for diagnosis and treatment for diabetes mellitus, this different from a study at primary care level which found that compliance of diabetic patients with most types of diabetes regimen was low[15]. Another study in Egypt showed more than three quarters (77.7%) of the diabetics adhered poorly to the prescribed diet and only (8.1%) adhered to it well[16]. In our study the subjects 40-59 age-group; among patients having secondary and higher level education, the prevalence of unhealthy diet was several times higher among hospital patients. In another study there was a statistically significant difference between education and compliance with dietary management of diabetes, nearly one quarter (25.8%) of illiterates were not compliant with dietary management of diabetes. Half of recently detected diabetics (less than one year) were more frequently compliant with dietary management of diabetes, however, with increasing time elapsed they became less compliant. Concerning adherence to the prescribed diet, 41.7%, 38.8% and 19.4% were more frequent, less frequent and non-compliant with dietary management of diabetes respectively[13]. In our study; among married patients the percentage of unhealthy diet was almost twice among hospital patients (p < 0.001). Also the prevalence of unhealthy diet was significantly higher among non-obese hospital patients than the non-obese PHC patients (p = 0.001)A study at primary care level has found that compliance of diabetic patients with most types of diabetes regimen was low. Increase in the level of patient's knowledge of diabetes was associated with better compliance. It was clear from this study that the better the degree of doctor-patient relationship the better degree of the compliance on diet. It also showed that 92.1 % of patients were sometimes compliant on diet while only 2.2% of them were always compliant[15]. A study in Saudi Arabia found that there was good compliance by 40% of Saudi patients with dietary regimen[23]. Another study in Egypt showed more than three quarters (77.7%) of the diabetics adhered poorly to the prescribed diet and only (8.1%) adhered to it well[16]. Only 32.3% (n=41) of subjects exercise for 3 to 7 times per week, where as 67.7% of them (n=75) exercise only 0 to 2 times per week. This study clearly showed that the rate of compliance towards exercise recommendation was still low among the patients. This result was supported by many other studies done. Various studies reported that only 15-70% of respondents met the minimum recommended exercise regimen, which is 3 times per week, minimum 20 minutes. There were many factors leading to low compliance rate of exercise regimen among patients with diabetes mellitus. This study showed that the most possible factor for exercise noncompliance is environmental factor, in the sense of ‘lacking of time to exercise’, ‘poor health condition’, ‘busy with work’, ‘tired’ and ‘having no companion or partner’, as answered by most patients. Almost the same factors reported by other studies, for example two studies revealed the barrier to exercise as ‘lack of time to do’ and ‘too busy to exercise. Poor health condition resulted from diabetic complications such as extremity ulcers and associated diseases such as arthritis also reported as common barriers to comply with exercise regimens[24]. The risks associated with exercise are considered less than those of inactivity, even in older adults with multiple chronic diseases. Therefore, exercise training should be an essential component of any treatment plan for all patients at risk of or with T2DM[25].In a community-based study in Egypt, it was found that there is no significant difference between genders; however younger patients are more compliant on treatment regimen. When comparing the mean score of each type of the compliance items separately, it was found that the lowest mean scores were recorded for the compliance of the patients with exercise. It was also found that diabetic coma and other complication were significantly more encountered among poor compliers than good ones. The mean reasons for poor compliance with diet were difficulty in changing habits, far working distance, lack of knowledge and poverty, whereas poor compliance with exercise was caused by lack of knowledge, no time and disability[26].Among patients with diabetes, the benefits of regular physical activity have been well documented. It was shown that restrictions on dietary freedom have a major negative impact on QoL . We found a significant association between the compliance to diet and well-being subscale scores (except for the energy sub score). We also found significant association between regular physical exercise and all subscale scores of well-being. This can be related to better compliance for the disease or to being a good self-manager of this chronic condition. Patient's being able to achieve the recommended life style changes may contribute to the well-being of the diabetic patient[27].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This study was made possible by a research grant from the Deanship of Research, Qassim University, Saudi Arabia, and was conducted with permission from the Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The authors are fully responsible for the contents of the study; views expressed are not necessarily those of the Ministry of Health, Deanship of Research or Qassim University. We are indebted to the staff of the MOH involved for their cooperation and assistance in data collection.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML