-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2012; 2(6): 185-189

doi:10.5923/j.phr.20120206.02

Clinico-Epidemiological Profile of Extra Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Report from a High Prevalence State of Northern India

Vishav Chander1, SK Raina1, AK Bhardwaj1, S Kashyap2, Anmol K Gupta3, Abhilash Sood1

1Department of Community Medicine Dr. R.P. Government Medical College Tanda (Himachal Pradesh), India

2Department of Pulmonary Medicine-cum-Principal Indira Gandhi Medical College, Shimla (Himachal Pradesh), India

3Community Medicine Indira Gandhi Medical College, Shimla (Himachal Pradesh), India

Correspondence to: SK Raina, Department of Community Medicine Dr. R.P. Government Medical College Tanda (Himachal Pradesh), India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Background: Extra pulmonary tuberculosis is substantially higher in Himachal Pradesh state of India than the national average according to the available data. Aim: The aim of the study was to understand the clinco-epidemiological profile of patients diagnosed as EPTB cases. Material and Methods: The study was a questionnaire based cross sectional survey in low and high prevalence Tuberculosis Units of Himachal Pradesh. Results: Of the 86 patients enrolled, 70.9% were from high prevalence TU and 29.1% were from low prevalence TU. Mean age of the patients was 26.67 ± 11.72 years. Of 86 patients 57 (66.3%) were in the age group of 15 – 34 years. Overall, pleural TB was the most common type of EPTB followed by lymph node TB (53 cases, 61.6% and 20 cases, 23.2% respectively).

Keywords: Clinico-Epidemiological Profile, Extra Pulmonary Tuberculosis, Prevalence

Cite this paper: Vishav Chander, SK Raina, AK Bhardwaj, S Kashyap, Anmol K Gupta, Abhilash Sood, Clinico-Epidemiological Profile of Extra Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Report from a High Prevalence State of Northern India, Public Health Research, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 185-189. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20120206.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- World Health Organization (WHO) reports that about two billion i.e. nearly one third of the world’s population is currently infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Developing countries account for 95% of the burden of tuberculosis (TB) and 99% of the TB mortality reported worldwide.[1] Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) has low infectivity as compared to pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), yet it cannot be ignored as it contributes a substantial proportion of the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program’s (RNTCP’s) case load.[2] Not only the proportion of EPTB cases out of all TB cases varies widely from region to region, country to country and within countries/states but the pattern of site involved also varies. Data before the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) era indicated that despite the decline of pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), the number of cases of EPTB remained constant; as a result the proportion of all reported cases of EPTB has risen from 7.8% in 1964 to 14.9% in 1981 and It again rose from 18% in 1996 and 20% in 1999.[3] Since the mid 1980’s most of the literature on EPTB is in association with AIDS. Extra-pulmonary involvement can be seen in more than 50% of patients with concurrent HIV and TB.[4] Globally, on an average one in five (20%) registered tuberculosis patients has extra-pulmonary tuberculosis.[5]However, data shows that the proportion of EPTB is substantially higher in the state of Himachal Pradesh when compared with the national average of 17-18%.[6] Although dual infection with TB and HIV has been known to be factor for high prevalence of EPTB, this is unlikely cause of high prevalence of EPTB in Himachal Pradesh (and Shimla district) which is classified low prevalence state (HIV prevalence less than one percent in antenatal women).[7]

2. Material and Methods

- The study was conducted in Rampur and Chaupal Tuberculosis Units (TUs) of district Shimla. The TUs form a part of state public health care infrastructure which provides most of the services with regard to Tuberculosis. The people of Himachal Pradesh find higher value in the care provided by government facilities than do many Indians in other states.[8] Data from three recent surveys analysed in a report by Princeton University, suggests that between 56 percent and 79 percent of service delivery is from government providers, compared to rates of 20 percent and lower in many other states.[8]All new EPTB cases registered between 1st July 2007 and 31st March 2008 in selected TUs (TU Rampur and TU Chaupal) were selected for the purpose of study. These two TUs were selected out of four TUs in the district Shimla – one with highest proportion of new EPTB cases and the other with least proportion of new EPTB cases out of all new TB cases. Rampur TU had reported highest proportion (47.2%) of new EPTB cases during the first (41%) and second (53.3 %) quarters of the year 2007 (average 47.2 %). Chaupal TU had reported minimum proportion (19% and 25.6% respectively; average 22.7% for these two quarters) of new EPTB cases during the same period .[9,1])

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- • All new cases of EPTB put on DOTS between 1st July 2007 and 31st March 2008 • Patients not switched on to non-DOTS treatment at the time of study.• Patients willing to participate in the study.

2.2. Exclusion criteria

- • Patients who were seriously ill and hospitalized at the time of data collection were not included in the study.• Patients transferred in or transferred out during the study period.• The patients who had completed their treatment at the time of start of study.• Those patients who could not be traced at respective DOTS centre and at their residence even after paying two visits. A pre designed and pre tested structured questionnaire was used to collect information. A pre test was carried out in one of the TUs in Shimla district, which was not included in the study sample. Appropriate changes were made in the schedule taking into consideration the experiences of the pre test. After appropriate changes the revised questionnaire was administered on all patients diagnosed as suffering from EPTB and following information was collected:• Demographic characteristics of selected patients• Clinical and/or laboratory criteria used for diagnosing the selected EPTB patients • Details of the institutions where the diagnosis of EPTB patient (s) was established.The information obtained in interview was crosschecked with the relevant records like TB Register, Laboratory Register and Treatment Cards.On the start of study, Rampur TU was visited and a list of the EPTB cases diagnosed and registered between 1st July 2007 and 31st March 2008 was prepared. The list of DOTS centres from where those patients received ATT was also prepared. The DOTS centres were visited on Monday, Wednesday or Friday to locate the EPTB cases, interviewed them and checked their treatment cards after obtaining the prior informed consent. If any patient did not visit the centre on the scheduled DOTS days, he/she was traced to his/her home and interviewed there only. Once all the EPTB cases had been interviewed in Rampur TU area, the process was repeated in the Chaupal TU till both TU areas were covered. The data collected was entered into MS Excel spreadsheet 2003. Both descriptive and analytical analyses were done using statistical package SPSS version 10.0.1. Chi Square Test was used to analyse qualitative data.

3. Results

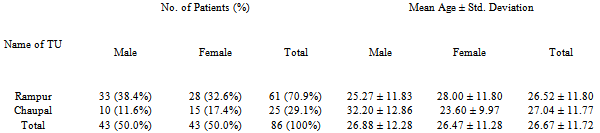

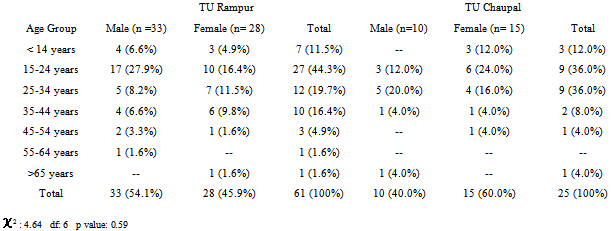

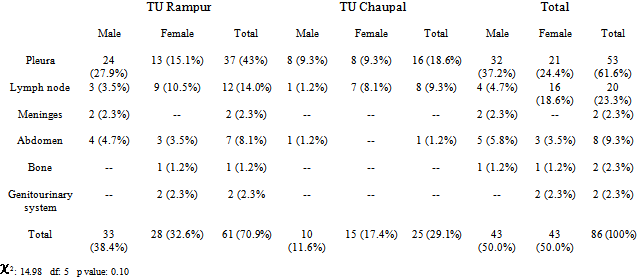

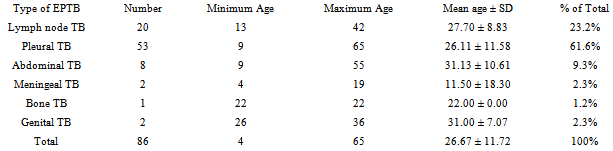

- In TU Rampur, 70 new EPTB cases were registered during the study period. Out of these (70 cases) , one case was over reported, two sputum negative PTB cases were wrongly recorded as EPTB cases, two patients died during the treatment and one case was later proved to be suffering from ovarian malignancy. Three patients could not be traced after paying two visits. So the sample size in TU Rampur constituted 61 new EPTB patients.Similarly 28 new cases of EPTB were registered during the same period from Chaupal TU. Of these, two cases were transferred-in cases from other TUs and one patient could not be traced even after two visits. 25 cases from TU Chaupal were thus included for the purpose of conducting the study. Thus the total study sample comprised of 86 patients only.The overall mean age of EPTB patients was 26.82 ±11.71 years (26.88 ± 12.28 years in males and 26.76 ± 26.76 years in females) as shown in table I. In TU Rampur, the overall mean age of EPTB cases was 26.73 ± 11.78 years (25.27 ± 11.83 years in males and 28.52 ± 11.70 years in females). Similarly, the overall mean age of EPTB patients in TU Chaupal was 27.04 ± 11.77 years (32.20 ± 12.86 years and 23.60 ± 9.97 years in males and females respectively). In the present study, the majority of patients were in the age group of 15 – 34 years constituting 66.3% of the all cases. Children < 14 years constituted 11.6% of the all cases, whereas, only 22.1% patients were over 35 years of age. The age group having the highest percentage of EPTB was 15 – 24 years (41.9%).Out of the total 86 cases in the present study, 43 (50.0%) were males and 43 (50.0%) were females (Table 1 & 2) In TU Rampur, 33 (38.4% of total cases) were males and 28 (32.6% of the total cases) were females. However, females constituted a higher proportion 15 cases (17.4% of the all cases) than the males 10 cases (11.6% of the all cases) in TU Chaupal.In the present study, pleural TB was found to be the most common type of EPTB 53 cases (61.6%), followed by lymph node TB in 20 cases (23.2%) and abdominal TB in 8 cases (9.3%) as shown in Table 3 & 4. Smaller proportion of EPTB comprised of, Meningeal TB 2 cases (2.3%), genitourinary TB 2 cases (2.3%) and bone TB 1 case (1.2%). Female patients showed a predilection for the lymph nodes (16; 18.6% in women vs. 4; 4.7% in men). The pleura were a more common site of involvement in men than women (32; 37.2% in men vs. 21; 24.4% in women).

4. Discussion

- The present study was aimed at understanding the profile of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis in Himachal Pradesh. The profile reflects on the prevalence of EPTB across all age groups and both sexes. No particular age group is free of EPTB. Although the major contribution to EPTB in our study comes from adolescent and early adult age group, the paediatric patients constitute a good (11.6%) portion of all EPTB cases. EPTB generally affects younger age group.[2 & 11] The present study also corroborates this. Similar finding of involvement of younger age in EPTB has been observed in Minnesota[12] in which 43% of the EPTB patients were in the age 15 - 24 years. In another study carried out in Fars Province, Southern Republic of Iran, highest number of EPTB patients were in the age 15-24 years (30.7%) followed by age group 25-34 (24.3%).[13] A study from South Delhi, India also shows the similar finding; 38% of the patients were in the age 15-24 years followed by 25% in age 25-34 years. In a review of EPTB cases in the RNTPC in India, paediatric cases (0-14 years) comprised almost 15% of all EPTB cases.[2] The findings are similar to studies conducted in different parts of world. In a study conducted in the largest private tertiary care hospital in Karachi, Pakistan, the mean age of patients was 34 ± 16.4 years and 75% were female patients. About two third of the patients were in the age group of 15 – 44 years.[18] In another study from Yemen, 93% of the patients with EPTB were in the age group of 15 – 54 years and 62% were females.[19]Different studies show different pattern of EPTB site involvement. Some studies show pleural TB to be the most common type of EPTB whereas in other studies lymph nodes were found to involved most frequently. In the present study, pleural TB was found to be the most common type of EPTB. In a study in Pereira, Colombia, pleural TB (48%) was found to most frequent form of EPTB followed by Meningeal (18.6%) and lymph node TB (12.7%).[14] A study from Madagascar also showed pleural TB (77.4%) to be the most common type of EPTB followed by lymph node TB (8.6%) and abdominal TB (7.2%).[15] In a similar study from Hong Kong, the most common organ involved was pleura (41.2%) followed by lymph nodes (36.5%), genitourinary (4.5%) and gastrointestinal (3.5%).[3] In a study from Karachi, Pakistan, lymph node TB and spine were the most common sites involved (60%) followed by central nervous system, abdomen and musculoskeletal system.[19] However, in a study from Calgary, Canada; the lymph nodes were the most frequent site of EPTB involvement (43.5%), followed by pleural effusion (14.9%) and miliary TB (5.1%).[16] In a retrospective analysis of TB patients from Nepal also showed lymph nodes to be the most frequent EPTB site involved followed by abdominal TB (42.6% and 14.8% respectively).[17] Study from South Delhi also showed the similar pattern of EPTB site involvement with lymph node being the most frequent EPTB site involved (53.7%), followed by pleural involvement (28.7%), bone and joints (7.0%) and abdominal (6.7%).[2]The high prevalence of EPTB in Himachal Pradesh is a cause of concern and should be the research question for future in EPTB. Limitations of the studyBeing a study on a small sample size, the true prevalence of EPTB for the state is not reflected in this study. The data was collected primarily on the basis of recall method. So there is a probability of recall bias by the patients. The present study did not study the association of HIV by carrying out HIV serology that has been presumed to be associated with rise in EPTB cases in developed countries

|

|

|

|

6. Conclusions

- In spite of the limitations in this study, it does open up chance for future research in understanding extra pulmonary tuberculosis in our part of world. Extra pulmonary tuberculosis as already mentioned is much more commoner in our setup than in other parts of India. The fact that the study shows interalia that Pleural TB was the most common form of extra pulmonary tuberculosis in our study population allows us to plan for management of tuberculosis in a better way.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML