-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2012; 2(6): 180-184

doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20120206.01

Investigating the Causes of Infant Mortality in Akoko South West Local Government Area of Ondo State, Nigeria

G. O. Ayenigbara, V. B. Olorunmaye

Science and Technical Education Department, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko Ondo State, Nigeria

Correspondence to: G. O. Ayenigbara, Science and Technical Education Department, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko Ondo State, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This study investigated the causes of infant mortality in Akoko South West Local Government Area of Ondo State. Descriptive survey research design was used for the study while the population comprised all nursing mothers in the local government area from which 210 respondents were randomly selected as sample. Self constructed and validated questionnaire, with reliability index of 0.74 was used for data collection. With the help of two trained research assistants, the researchers administered the instrument and collected them back on the spot. The collected questionnaire forms were screened, coded into frequency tables and analysed with simple percentage and chi-square statistics. The finding showed that too frequent pregnancies, age of expectant mother, poor nutrition, poverty and lack of adequate medical care caused infant mortality in Akoko South West Local Government Area of Ondo State. Consequent upon these findings, it was recommended, among others, that free and compulsory education be provided for females up to the University level, and that teenage marriage be abrogated in the country.

Keywords: Infant Mortality, Neonatal Mortality, Post neonatal Mortality, Poor Nutrition, Poverty, Teenage Pregnancy, Low Birth Weight

Cite this paper: G. O. Ayenigbara, V. B. Olorunmaye, "Investigating the Causes of Infant Mortality in Akoko South West Local Government Area of Ondo State, Nigeria", Public Health Research, Vol. 2 No. 6, 2012, pp. 180-184. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20120206.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Infant mortality rate is one of the most important indications of human development. Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) according to[1] is the number of deaths of infants under one year of age per 1000 live births in a given year. Included in the IMR are the neonatal mortality rate (calculated from deaths occurring in the first four weeks of life), and post neonatal mortality rate (from deaths in the remainder of the first year). Neonatal deaths are further subdivided into early (first week) and late (second, third and fourth weeks). In prosperous countries, neonatal deaths account for about two-third of infant mortalities[2]. The IMR is usually regarded more as a measure of social affluence than a measure of the quality of antenatal and obstetric care.The infant mortality rate is widely accepted as one of the most useful single measure of health status of the community. The infant mortality rate may be very high in communities where health and social services are poorly developed. For example, the neonatal death rate is related to problems arising during pregnancy (congenital abnormalities, low birth weight); delivery (birth injuries, asphyxia), afterdelivery (tetanus, other infections). Thus, neonatal mortality rate is related to maternal and obstetric factors.The post neonatal mortality rate on the other hand, is related to a variety of environmental factors and especially, to the level of child care. However, experts[2] affirmed that poverty, inadequate health care, congenital problems, infectious diseases and injuries are the causes of infant mortality. Another cause is sudden infant death Syndrome (SIDS) which in the United States of America, accounted for about 2,800 infant deaths per year[2].Cigarette smoking is another factor in high infant mortality rate. Female smokers have an increased risk of preterm delivery, still-birth, low birth weight infants, and sudden infant death syndrome[3]. Also, pregnant women who smoke double their chances of delivering a still born infant, and they also double their risk of having an infant die during the first year of life[4].In addition, poverty is also a health risk in infant mortality. Indeed, the health risk associated with poverty begin before birth. Even with the expansion of prenatal care by Medicaid poor mothers, especially teen-mothers, are more likely to deliver low-birth-weight babies, who are more likely than normal-birth-weight infants to die[5]. Also pregnant women living below the poverty line are more likely than other pregnant women to be physically abused and to deliver babies who suffer the consequences of prenatal child abuse[6].Education is another risk factor in infant mortality. Education confers intelligence and erodes ignorance. Intelligence, according to[7] predicts both health and longevity. In addition, educated people are more likely to be informed consumers of health care, gathering information on their diseases and potential treatment. Education is also associated with a variety of health-related habits that are positively related to good health and long life. For example, people with education are less likely than others to smoke or use illicit drugs[8], and they are more likely to eat balance diets and to do exercise.Moreover, education delays marriage. The number of years spent in high school and University prevents early marriage among female students and this invariably prevents teenage pregnancy which is a factor precipitating infant mortality in developing nations[5]. Besides, education is associated with income. People who attend college, and especially those who graduate from University have higher average income than those who do not, and they are more likely to have a better access to health care. Low income has an obvious connection to lower standards of health care[9]. Though, no nationally representative data are available for infant mortality rate in Nigeria, however, several hospital-based studies have been conducted in some parts of the country. In Sagamu, a peri-urban area in the South West, a study reported a rate of 51 deaths per 1000 live births[14]. It has been reported by[15] that there were sharp increases in the risk of prenatal mortality as a result of a decline in the use of maternal services following the introduction of use fees in 1994. Similarly, neonatal mortality rate, which reflects the quality of antenatal and delivery services and quality of child care, as well as the presence of congenital defects and malformation is estimated to be 35 per 1000 live birth by the 1999[16]. Also in 1980, NDSS showed the mortality rate of 85 per 1000 live births; in 1990, NDHS showed 91 deaths per 1000 live births; the 1991 census revealed a mortality rate of 93 per 1000 live births; while in 1999, NDHS showed a rate of 71 deaths per 1000 live births; and in 1999 MICS revealed a mortality rate of 105 deaths per 1000 live births. In addition, many developing countries still record infant mortality rate as high as 100 per 1000 live birth[17].Despite the inconsistencies in these rates, the fact remains that the infant mortality rate is very high in Nigeria. Consequently this paper investigated the likely causes of infant mortality in Akoko South West Local Government Area of Ondo State, using too frequent pregnancies, age of the expectant mother, poor nutrition, poverty, and lack of medical care as the independent variables, from which hypotheses were generated for the study.

2. Methodology

- Descriptive survey research design was used for the study and the population consisted of all the nursing mothers in Akoko South West Local Government Area of Ondo State from which 210 respondents were randomly selected as sample. The selection cut across the rural and urban areas of the local government.

3. Instrument

- The instrument used for data collection was self constructed questionnaire. The draft questionnaire was given to a jury of three experts in health education who ensured its face and content validity. The reliability index of the instrument was 0.74. Responses to the 25 questionnaire items followed the Likert 3 point scale of Agree (A), Do Not Know (DNK), and Disagree (D).

4. Data Collection

- Two trained research assistants helped the researchers to administer the instrument. The questionnaire forms were given to the literate nursing mothers to fill, while it was read to the illiterate nursing mothers, and the responses of their choice were ticked by the researchers and their assistants. Filled questionnaire forms were collected back on the spot. Retrieved questionnaire forms were screened, coded into frequency tables while simple percentage and Chi-square statistics were used for analysis of data.

5. Results

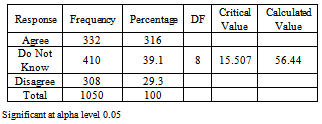

|

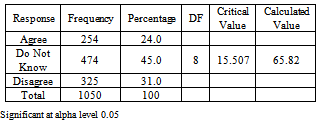

|

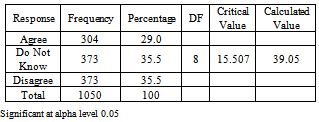

|

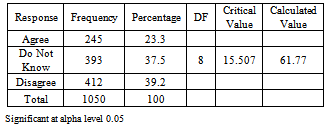

|

|

6. Discussion

- The result of this study showed that too frequent pregnancies significantly caused infant mortality in Akoko south West Local Government Area of Ondo State as indicated in table 1. Frequent pregnancies are common among the polygamists in Nigeria, where women compete in child bearing, with some women having up to 13 children[18]. The finding of this study supported the affirmation that there is high infant mortality rate of about two or four times with the babies born one year of a previous birth, as against the babies born at both ends of the intervals[11]. He further stated that a short interval does not give the mother sufficient time to recuperate from the birth and to replenish her stores of nutrient used during pregnancy, especially in conditions of malnutrition.Also, the findings revealed that the age of the expectant mother i.e teenage pregnancy significantly caused infant mortality in Akoko South West Local Government Area of Ondo State as shown in table 2. This finding corroborated experts[17], and[2] who noted that the age of the mother have some effects on the growing baby, for instance, certain defects like mongolism, congenital heart diseases, premature deliveries, still birth and infant deaths are all associated with old age and teenage pregnancies. Reference[2] asserted that about half of all cases of low birth weight (LBW) babies are related to teenage pregnancies which may cause infant mortality. Ignorance and poverty, which are common among teenage mothers and the Primigravidas are responsible for LBW babies, who are more likely than normal-birth-weight infants to die[10],[5].Furthermore, the findings showed that poor nutrition significantly caused infant mortality in Akoko South West Local Government Area of Ondo State as revealed in table 3. The finding supported experts[10] and[2] who reported that the survival of children is affected by the nutrition available to the children themselves and also to the mother. They argued that maternal diet during pregnancy affects birth weight and influence the quantity and quality of nutrients in the breast milk during lactation, which are likely to affect a child’s survival, especially, during their first year of birth. Also the lack of such nutrition makes the infants vulnerable to diseases like tuberculosis, measles, tetanus, polio, diphtheria, whooping cough and several diarrhea that kills the majority of babies in the third world[19]. Moreover,[10] observed that high (50%) mortality rates were recorded among artificially-fed infants in developing countries, in homes where bacterial contamination or incorrect formula preparations are common. The direct consequence of poor nutrition, during pregnancy, is low birth weight babies, the incidence of which is the likely contributing factor of infant mortality among African Americans[2].In addition, the result revealed that poverty significantly caused infant mortality in Akoko South West Local Government Area of Ondo State as shown in table 4. Infant mortality rates, according to[17] reflects the socio-economic status of the parents. Infant mortality rates are high where the socio-economic status of parents are low and vice-versa. The finding however agreed with[20] who observed that poverty is one of the most important factors affecting the infant mortality rate in Nigeria, contributing to lack of infrastructure, lack of education, poor nutrition and poor health outcomes. The country’s low socio-economic status adversely affects maternal child health because it limits access to adequate nutrition, quality health care, medication, safe water, adequate sanitation, and other basic social services[17]. Furthermore,[2] agreed that poverty and inadequate health care are key causes of infant mortality and results in a six fold increase in the risk of low birth weight if the mother had financial problems during the pregnancy. In the same vein, poor mothers’ are likely to give birth to LBW babies who may be victims of infant mortality[5].Finally, the findings of this study showed that lack of medical care significantly caused infant mortality in Akoko South West Local Government Area of Ondo State as revealed in table 5. This finding supported the assertion of the researchers who observed that lack of adequate medical care was a major problem confronting Nigerians, particularly, the mother and child health care. The finding further supported[17] who noted that various statistical indicators like infant and child mortality rates, and maternal mortality rate show the serious health problems that affect this group in developing countries like Nigeria. Reference[12] opined that a higher infant mortality occur among African Americans as a result of inadequate medical treatment. In support of this assertion, reference[2] who affirmed that poverty and inadequate health care are key causes of infant mortality. Even in the United States, African Americans, compared with European Americans, have shorter life expectancy as well as a higher infant mortality rate among other health problems[12]. Inadequate medical treatment may be a factor in this situation as African Americans receive poor care than European American resulting in high infant mortality[13], and this may be a more likely reason for high infant mortality in Nigeria.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The findings of this study showed that too frequent pregnancies as indicated in table1, caused infant mortality in Akoko South West Local Government Area (ASWLGA) of Ondo State. Also the age of the expectant mother(table2) caused infant mortality in the Local Government Area. The findings further showed that poor nutrition of the mother,(table3), caused infant mortality in ASWLGA of Ondo State. In addition the study revealed that poverty (table4) and lack of adequate medical care(table5) caused infant mortality in the Local Government Area of Ondo State. Sequel to these findings, the following recommendations were made:1. Health education should be introduced and made compulsory for students at all levels of education, not only in Akoko South West Local Government Area but throughout the country. Health education, with emphasis on personal hygiene, nutrition, consumer health etc. with its carry over value may help pregnant women and nursing mothers to take appropriate actions an issues relation to their health and that of their children. Health education should also be incorporated into the antenata, care and provided to pregnant women and nursing mothers in the maternity centres and hospitals.2. Free and compulsory education should be provided for female students up to the University level in Nigeria. Education up to the University level may delay marriage and thus prevent teenage pregnancy; it may also prevent ignorance; and enhance the income of the prospective mother. This may avert poverty among pregnant women and nursing mothers.3. Teenage marriage should be abrogated through legislation in the country to stem the tide of teenage pregnancies and its concomitant deleterious consequences. Enlightenment campaigns should be mounted to educate the public on the dangerous effects of teenage marriage. The support of traditional rulers, opinion leaders, social agents and agencies should be enlisted in this regard, and all cultures and traditions promoting teenage marriage should be abandoned.4. Mother and child hospitals should be established and located throughout the country to cater for pregnant women and nursing mothers free of charge. Pregnant women should be encouraged to go for medical care, and to deliver their babies in hospital or maternities rather than in their homes. So that effective monitoring, care and safe delivery could be done.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML