-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Public Health Research

p-ISSN: 2167-7263 e-ISSN: 2167-7247

2012; 2(5): 120-123

doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20120205.02

Training Opportunities for Environmental Health Staff in Kenya: Too Few?

John Njuguna 1, Charles Muruka 2

1Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, Ijara District, Kenya

2Environmental Health and Allied Services, P.O. Box 19185, 40123, Kisumu, Kenya

Correspondence to: John Njuguna , Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, Ijara District, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Environmental health officers play a key role in the delivery of preventive and promotive health services in Kenya. This is important given that Kenya is yet to make an epidemiological transition and still grapples with preventable diseases. Training opportunities and promotion are key motivators for this cadre of health workers. An analysis of the January 2007 environmental health staff returns for two districts was done with a view of determining frequency of promotions and availability of training opportunities for environmental health staff. Further details and clarifications were provided by the officer in charge of making staff returns. Only 18.4 % of staff who entered at the certificate level had managed to progress to the diploma level. On the contrary, 83% of those who entered at diploma managed to progress to the higher diploma stage. The mean period of promotion was 7.3 years. There was little difference between certificate and diploma holders in terms of the period of promotion. More training opportunities should be availed to enable the certificate holders progress to the diploma stage and be eligible for promotion. These may include scholarships, distance learning and professional bridging exams. Promotions should be regular and commensurate with one’s qualifications.

Keywords: Environmental Health Staff, Training Opportunities, Staff Promotion

Cite this paper: John Njuguna , Charles Muruka , "Training Opportunities for Environmental Health Staff in Kenya: Too Few?", Public Health Research, Vol. 2 No. 5, 2012, pp. 120-123. doi: 10.5923/j.phr.20120205.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Health workers are people engaged in actions whose primary intent is to enhance health 1. Sub Saharan Africa suffers from inadequate health workers 1, 2. Reasons for this shortage include migration of health workers to work in developed countries due to better terms; poor working conditions and the HIV/AIDS scourge among others 1, 2. To achieve the health related Millennium Development Goals 1, 3, there is need to scale up access to key interventions like antiretroviral therapy, TB and malaria treatment. Other than the need to supply drugs and commodities, adequate and well motivated health workers are key to the scaling up of these interventions.Kenya is a lower middle income country (LMIC) with an estimated population of 30 million people. It still grapples with preventable diseases, which account for approximately 80% of hospital attendance and 50% of which are water, sanitation and hygiene related 4. Public health workers have been classified into 3 key subsets, the ‘specialist’, ‘practitioner’ and the ‘wider non-specialist workers’. Environmental health officers are at the frontline of the public health practitioners 5. It has been argued that the ‘specialists’ tend to make significant progress in developing their skills and employment opportunities relative to the other two groups. This is because they tend to have more effective professional leadership and it is easier for policy makers to develop a few specialists rather than a much larger and diverse number of professionals 6.

1.1. Role of Environmental Health Officers

- From time immemorial, health officers have played a key role in securing the well being of the masses. Plato (427-347 BC) and Aristotle (384-322 BC) stated that no city should exist without health officers, positions which in ancient Greece were filled by such notable figures like Demosthenes 7. Environmental health officers play a key role in providing preventive and promotive health services from the cities right to the village and homestead levels. These include communicable disease control, water quality control, food safety, solid and liquid waste management, vector control and health education 8. They also generate revenue for the government and enforce public health laws, key of which is the Public Health Act. This is an act of Parliament to make provision for securing and maintaining health 9.At the district level, environmental health officers are normally in charge of disease surveillance, AIDS and sexually transmitted infections control. They also sit on various boards. These include the district health management team, district liquor board and district development committee. They are also involved in the planning, implementation and evaluation of community based health projects. These entail capacity building of communities, construction and equipping of health facilities and promotion of hygiene and sanitation.Environmental health staff comprise of two categories, namely technicians and officers. The former hold a two year certificate from the Medical Training College and the latter a three year diploma from the same. To upgrade from a technician to an officer, one has to undertake two years training at the Medical Training College.

1.2. Motivation of Health Workers

- Factors affecting attraction and retention of health workers have been recently classified as ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors. "Pull" factors are identified as those which attract an individual to a new destination. These might include improved employment opportunities and/or career prospects, higher income, better living conditions or a more stimulating environment. 'Push' factors are those which act to repel an individual from a location. They may include poor living conditions, lack of schools for children, low wages and loss of employment opportunity10. Some economic theories try to explain health workers mobility e.g. the Neoclassic Wage Theory, which suggests that the choice is driven largely by financial motives and by the probability of finding employment10. In this sense, it has been argued that "a health worker will accept a job if the benefits of doing so outweigh the opportunity cost”10.Willis-Shattuck and colleagues 3 did a systematic review on motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries and came up with seven key factors. These are financial incentives; career development; continuing education; work environment; equipment and medical supplies; hospital management; personal recognition and appreciation. They later came up with three core motivational factors. These are financial incentives; career development and management issues. Training opportunities and promotions are important motivators. This is considering that environmental health workers cannot engage in private practice like other medical workers like doctors, nurses and laboratory technicians.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

- Nyandarua North and South districts are located in Central Province of Kenya. They were both part of the larger Nyandarua district which was split into two districts in 2006. Both districts have an estimated population of 583,006 as of 2007 12; a total area of 3,304 km2 and a density of 145 persons per square kilometre. These two districts constitute 0.6% of Kenya and 26.7% of Central Province. Each district has an environmental health officer in charge who is assisted by officers and technicians under him.Nyandarua North and South districts Environmental Health Staff Returns for January 2007 were analysed. Analysis was done using SPSS version 11. Further information and clarifications were provided by the officer in charge of making staff returns.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographics

- The two districts are staffed by 97 environmental health staff. Females comprise of 21.6% and males 78.4%. Majority of females are certificate holders (95.2%) compared to males (71.1%). The mean age was 42.7 years; mean working experience was 18 years. Mean period since last promotion was 7.3 years.

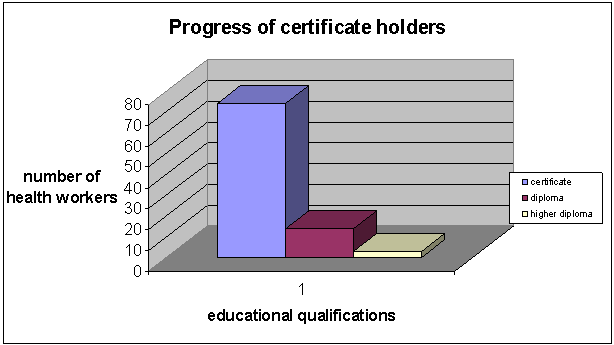

3.2. Educational Advancement and Promotion

- Currently 76.3% of the health workers are certificate holders, 15.5% diploma holders and 8.2% higher diploma holders. When they entered service, 93.8% were certificate holders and 6.2% were diploma holders. The level of advancement is as follows: 18.4% of certificate holders managed to advance to diploma and higher diploma stages, while 83.3% of diploma holders managed to advance to the higher diploma stage. There was a significant correlation between level of entry and current level (0.629 Pearson Correlation).From a gender perspective, males were more likely to be holders of diploma and higher diploma compared to their female counterparts (OR 6 95% CI 0.87-42.5). There was no significant correlation between current educational status and the period in years since the last promotion (-.017 Pearson Correlation)

4. Discussion

- Only a small portion of certificate holders managed to advance to the diploma stage and 76.3% are still stuck at the certificate level. A survey among Environmental Health Officers working in four sub-Metropolitan districts in Kumasi and Accra in Ghana found the staff had relatively low levels of training and education with 76.5% being basic grade Environmental Health Assistant, the equivalent of Environmental Health Technicians in Kenya. This workforce was also found to be an ‘ageing one’ with 53% of respondents being over 40 years. 15 The staff in the two districts have a mean age of 42.7 years. Lack of younger staff could be attributed to the government freeze on employment as part of donor conditionality. The survey in Ghana found that the younger officers were the worst educated, while this study found the younger officers more likely to be better educated compared to their elder counterparts as they are more inclined to go back to school. Recently the ministry of health abolished the certificate training. Those who are certificate holders apply to the Kenya Medical Training College for a two years course leading to a diploma. No scholarships are provided; one is only granted study leave and maintained on the payroll.Certificate holders comprise majority of environmental health workers. Admission to the medical training college is pegged on available accommodation. This leads to many health workers who apply missing places. Though the health workers regular undergo continuous education and short courses on water and sanitation; food safety and management of the cold chain. These courses do not count much when it comes to promotion. Nurses who want to advance from a certificate to diploma have the option of enrolling for a distance learning program. They attend classes as they continue working. They go to classes for short periods of time during which they write exams. For environmental health workers, they have to enrol full time. Diploma holders are few relative to certificate holders and are more likely to advance faster academically. Health workers with fewer working experience are more likely to go back to college compared to those with more experience. This may be due to the fact that they have more years of service and the prospects of better terms of service motivates them to advance academically. From a gender perspective, females are more disadvantaged compared to their male counterparts. There is no plausible explanation for this. This study could not access data on admissions to the medical training college so as to ascertain whether admission is skewed in favour of men.There is no correlation between current level of education and period since the last promotion. There are higher diploma holders and certificate holders who have been stuck in the same job group for over ten years. Acquisition of more qualifications does not automatically lead to promotion and this has lead to both cadres of workers being stuck in a rut. This may discourage other health workers from going back to college, considering that they have to meet the costs themselves. The study made use of staff returns and this may be liable to under reporting or missing data. This may have led to bias. In the near future it is suggested that the health workers be interviewed. This will bring out perceived obstacles to pursuing further studies and promotion related issues.

5. Conclusions

- Training opportunities are far and few for environmental health workers and many of them are not pursuing further studies after leaving college. Advancing academically does not automatically lead to promotion. This implies that more training opportunities should be availed given the important role played by this cadre of health workers. One feasible option is introduction of distance learning. This will facilitate learning as one works. Many health workers can enrol as enrolment is not pegged to accommodation places available. Promotions should be regular and automatic per given number of years worked. It should also be hinged on educational advancement so as to encourage environmental health workers to pursue higher studies.

|

|

| Figure 1. Progress of certificate holders |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- I am grateful to Mr Michael G Gichuru for providing further inputs and clarifications concerning the staff returns; Mr Philip Kuria and Mr Joseph Nganga District Public Health Officers, Nyandarua North and South districts respectively.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-Text HTML

Full-Text HTML