-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Otolaryngology

p-ISSN: 2326-1307 e-ISSN: 2326-1323

2018; 7(1): 1-4

doi:10.5923/j.otolaryn.20180701.01

Impact of Concha Bullosa on Osteomeatal Complex Drainage and Septal Deviation

Rajashree, Faheema Ahmed Ali, Deepthi P., Viswanatha B.

Otorhinolaryngology Department, Bangalore Medical College & Research Institute, Bangalore, India

Correspondence to: Viswanatha B., Otorhinolaryngology Department, Bangalore Medical College & Research Institute, Bangalore, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

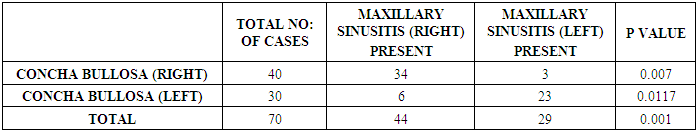

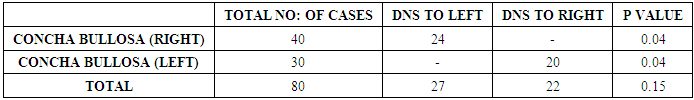

Aim: To know the association between unilateral concha bullosa and the development of ipsilateral maxillary sinusitis and nasal septal deviation to opposite side. Introduction: Concha bullosa or pneumatisation of middle turbinate is the most common anatomical variation seen in nose. Pneumatisation of middle turbinate may lead to obstruction of osteomeatal complex, which interferes with the drainage of anterior group of paranasal sinuses, most commonly maxillary sinus. Nasal septum may get deviated with convexity to other side due to constant pressure of pneumatised middle turbinate. Materials and methods: A cross sectional study was done, where 70 cases of unilateral concha bullosa were included after radiological and endoscopic assessment. Patients with unilateral concha bullosa were assessed for the presence of osteomeatal blockage and inflammatory changes in ipsilateral maxillary sinus and also for the presence of septal deviation to the opposite side. Results: There were 70 patients with unilateral concha bullosa, of which 57 cases (81%) had ipsilateral chronic maxillary sinusitis and there was statistically significant association between them. Among 70 cases of unilateral concha bullosa, 44 cases (62%) showed septal deviation to the opposite side, which was not statistically significant. Conclusion: In our study, the presence of unilateral concha bullosa was associated with increased chances of osteomeatal complex blockage and the development of ipsilateral maxillary sinusitis. There are increased chances of septal deviation to the opposite side with unilateral concha bullosa.

Keywords: Concha bullosa, Osteomeatal complex drainage, Septal deviation

Cite this paper: Rajashree, Faheema Ahmed Ali, Deepthi P., Viswanatha B., Impact of Concha Bullosa on Osteomeatal Complex Drainage and Septal Deviation, Research in Otolaryngology, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2018, pp. 1-4. doi: 10.5923/j.otolaryn.20180701.01.

1. Introduction

- Concha bullosa is defined as pneumatisation of middle turbinate [1]. It is one of the commonest anatomical variations seen in the nose. Middle turbinate pneumatisation occurs as a part of normal pneumatisation of ethmoidal air cells. Concha bullosa can be classified into three varieties based on the parts involved, lamellar: which involves the vertical part of middle turbinate, bulbous: involving horizontal part, mixed: which involves both horizontal and vertical part [2].The air cavity in a concha bullosa is lined by the same epithelium as the rest of the nasal cavity; these cells can undergo the same inflammatory disorders experienced in the paranasal sinuses. Obstruction of the drainage of a concha bullosa can lead to mucocele formation [3].Osteomeatal unit is a functional unit of the anterior ethmoid complex representing the final common pathway for the drainage and ventilation of the frontal, maxillary and anterior ethmoid cells [4].Certain anatomic anomalies may contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis, which includes septal deviation, paradoxical middle turbinate; concha bullosa and large ethmoid bulla by obstructing osteomeatal complex as it interfere with the drainage of anterior group of paranasal sinuses [3].Osteomeatal complex has become an area of active radiologic and pathophysiologic investigation with the development of endoscopic sinus surgery for inflammatory sinus disease. The concha bullosa should be addressed in patients with rhinosinusitis undergoing surgery, primarily because its removal improves visualization of the middle meatus. There are also reports of mucoceles within a concha bullosa causing symptoms of rhinosinusitis [3].When unilateral concha bullosa is present, nasal septum gets deviated with convexity to the opposite side so the air column between the concha bullosa and septum is maintained. The septum which is deviated to the opposite site may produce symptoms of obstruction and in gross deviation it may obstruct the osteomeatal complex contributing to the development of chronic sinus disease [5].This study was conducted to know the impact of unilateral concha bullosa and osteomeatal blockage causing chronic sinus disease, mainly maxillary sinusitis and nasal septal deviation with convexity to the opposite side.

2. Materials and Methods

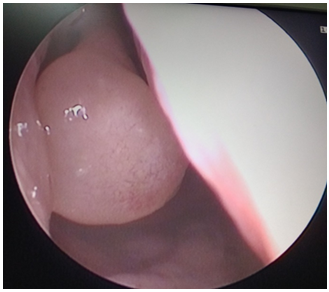

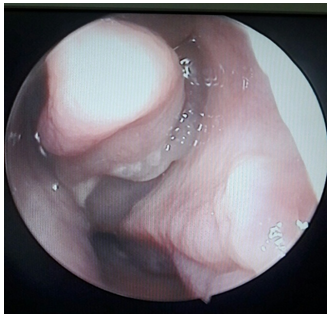

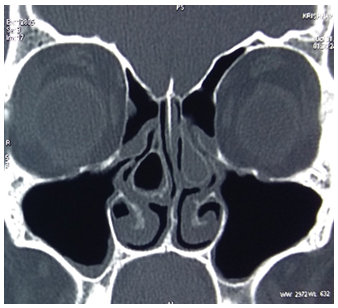

- A cross sectional observational study was done for a time period of 6 months, from July 2017 to December 2017 in department of otorhinolaryngology. Before commencement, written consent from all patients was obtained. Study involved 70 cases which showed unilateral concha bullosa. Presence of concha bullosa was assessed by diagnostic nasal endoscopy and confirmed by using computed tomography (CT) of nose and paranasal sinuses.Patients coming to the department of otorhinolaryngology were subjected to thorough clinical examination, and assessed using diagnostic nasal endoscopy (DNE). Before the procedure, both the nasal cavities were medicated with decongestant nasal drops and 4% lidocaine with adrenaline.Procedure involves three passes, in first pass the 0° endoscope (or 30° endoscope) was passed gently along the floor of the nasal cavity between the inferior turbinate and septum without touching either. The septum was studied for any spurs and deviations. The inferior turbinate was examined for hypertrophy, especially at its posterior end. Any pathology obstructing the posterior choana was noticed, on withdrawing the scope the inferior turbinate and septum was reviewed.In second pass, the scope was passed along the floor up to the posterior choana. It was then moved upward medial to the middle turbinate along the roof of the posterior choana and the anterior surface of the sphenoid. The superior turbinate and meatus were seen. The sphenoethmoidal recess was visualized.The third pass was done to examine the contents of the middle meatus. The middle meatus was entered gently retracting the middle turbinate medially with the Freer’s elevator. The scope was then withdrawn from posterior to anterior to view the contents of the middle meatus. Quite commonly it may be ballooned out due to an air cell enclosed within it (Concha Bullosa) (Figure 1 & 2). This air cell may be pneumatised from the frontal recess, agger nasi cell or anterior ethmoids.

| Figure 1. Endoscopic picture showing concha bullosa on right side |

| Figure 2. Endoscopic picture showing discharge from the maxillary sinus |

| Figure 3. CT scan showing pneumatised middle turbinate |

| Figure 4. Showing concha bullosa on left side with mucosal thickening in the ipsilateral maxillary sinus |

3. Results

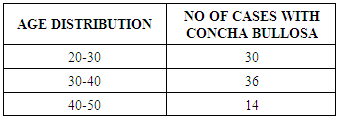

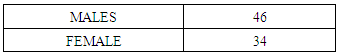

- Among these, 46 cases (57%) were male and 34 cases (42%) were female. Age group of subjects ranged between 21 to 50 years (table 1 & 2).

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The middle turbinate may show different anatomical variations. Quite commonly it may be ballooned out due to an air cell enclosed within it. This air cell may be pneumatised from the frontal recess, agger nasi cell or anterior ethmoids. In such a case the middle turbinate is called the concha bullosa. This balloon like concha bullosa may block the osteomeatal unit and the drainage of the anterior group of sinuses. Stallman defined concha bullosa as being present when more than 50% of the vertical height (measured from superior to inferior in the coronal plane) of the middle turbinate is pneumatised [5]. Certain anatomic anomalies may contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis, such as septal deviation, paradoxical middle turbinate, concha bullosa and large ethmoid bulla [6].Some studies have defined a concha as any aeration of the middle turbinate, even if the aeration is restricted to the upper nonbulbous portion of the turbinate. Other reports have restricted the definition of a concha bullosa to those cases wherein the aeration extends caudally into the bulbous portion of the middle turbinate [7].Exact mechanism of formation of concha bullosa is not clear. It is considered that the airflow pattern of the nasal cavity plays an important role. This theory is named as “e vacue”. As the airflow is markedly reduced in the nasal cavity with convexity of the deviation, pneumatisation of the middle turbinate is augmented in the contralateral site. This theory can explain the association between contralateral concha bullosa and nasal septal deviation [8].Hatipoğlu et al classified concha bullosa depending on the location of the pneumatisation as lamellar, bulbous and extensive. In his study, the incidence of concha bullosa was extensive type (46.95%), bulbous type (32.17%) and lamellar type (20.86%) [9].According to Ünlü et al, no significant relation was demonstrated between concha bullosa and osteomeatal unit blockage; however, when the bulbous-extensive type was compared with the lamellar type, a significant correlation was found regarding osteomeatal unit blockage. They thus concluded that pneumatisation of the inferior portion of the middle concha has a role in osteomeatal unit blockage [10].Bolger et al. reported the incidence of concha bullosa as extensive type (15.7%), bulbous type (46.2%) and lamellar type (31.2%). Lamellar concha is characterized by pneumatisation of vertical lamella, Bulbous type defined by pneumatization of bulbous segment and Extensive type defined as pneumatisation of both components [2].Lewis ME. et al. reported the prevalence of concha bullosa as 24-53.6% [11], Lioyd et al. reported it as 24%, [12] Zineriech reported it as 34% [1]. The first case of massive concha bullosa causing secondary maxillary sinusitis was reported by Lee et al in 2008. [13] Stallman et al, concluded that there is no statistical relationship between the chronic rhinosinusitis on either side and presence of unilateral or dominant concha bullosa. However, he found a strong relationship between the presence of a unilateral or dominant concha and contralateral nasal septal deviation. As they also found that in most of the cases air channel between the concha bullosa and nasal septum is preserved, the cause for septal deviation cannot be attributed to the presence of concha bullosa. There is no statistical relationship between nasal septal deviation and the presence of any sinus disease [5].A recent study by Javadarshid et al has concluded that there exists no significant relation between the presence of concha bullosa and paranasal sinusitis [14].In a study by Shoib and Viswanatha, deviated nasal septum was found to be associated with significant sinonasal disease, especially a C-shaped deviated nasal septum and it showed statistically significant correlation [15].In our study, statistically significant association was found between the concha bullosa and ipsilateral sinusitis. But regarding septal deviation, even though concha bullosa acts as a factor for septal deviation with convexity on opposite side, there was no statistically significant association between them.

5. Conclusions

- This study showed that there was statistically significant association between unilateral concha bullosa and the presence of rhinosinusitis, mainly maxillary sinusitis on same side, as it can cause osteomeatal blockade on same side and also that it can act as a factor for septal deviation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML