-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Otolaryngology

p-ISSN: 2326-1307 e-ISSN: 2326-1323

2017; 6(2): 30-33

doi:10.5923/j.otolaryn.20170602.04

Severe Laryngomalacia and Its Surgical Management: A Prospective Study

Prem Kumar P., Diviya K. K., Kumaraswamy K.

Department of Pediatric ENT, Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health, Bangalore, India

Correspondence to: Prem Kumar P., Department of Pediatric ENT, Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health, Bangalore, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Objective: To understand the clinical presentation of severe laryngomalacia and its surgical management. Study Design: A prospective descriptive study conducted in a tertiary care centre over a period of 5 years (Jan 2012 to December 2016). Materials and Method: A total of ten patients who underwent surgical treatment for severe laryngomalacia at Indira Gandhi Institute of Child Health were included in the study. Their demographic profile, presenting complaints, surgical interventions, complications of the procedure and treatment outcomes were evaluated. They were followed up for a period of one year postoperatively. Results: A favorable outcome was seen in eight out of the ten patients who underwent aryepiglottoplasty with glossoepiglottopexy. Two patients required surgical reintervention. Conclusion: Aryepiglottoplasty with glossoepiglottopexy is a simple, safe procedure with a favorable outcome in 80% of patients.

Keywords: Severe laryngomalacia, Stridor, Endoscopic aryepiglottoplasty, Glossoepiglottopexy

Cite this paper: Prem Kumar P., Diviya K. K., Kumaraswamy K., Severe Laryngomalacia and Its Surgical Management: A Prospective Study, Research in Otolaryngology, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2017, pp. 30-33. doi: 10.5923/j.otolaryn.20170602.04.

1. Introduction

- In 1942 Jackson and Jackson were the first to coin the term laryngomalacia. (Greek malakia means morbid softening of an organ) [1]. Laryngomalacia is the most common cause of congenital laryngeal anomaly, followed by vocal cord paralysis second and subglottic stenosis third causing upper airway obstruction [2]. These findings equate with most of the available literatures. Although its pathogenesis is not fully understood, suggested causes include poor neuromuscular control with relative hypotonia of the supraglottic dilator muscles [2]. This causes collapse of supraglottic tissues generating a high frequency inspiratory stridor which is exacerbated on supine position, feeding, crying and agitation. Laryngomalacia can be classified as mild, moderate and severe. Infants who present with intermittent or positional stridor and mild feeding problems have mild laryngomalacia. Infants who present with persistent stridor and slow weight gain have moderate stridor. Patients who are classified as having severe stridor present with constant stridor, failure to thrive, deep retractions, pectus deformity, hypoxia, cyanotic spells, corpulmonale, vocal folds completely obscured on flexible laryngoscopy [3]. Although laryngomalacia is a self-limiting disease, 10% of these cases which present with severity will require surgical intervention.Surgical modalities of interventions in laryngomalacia can be done through microlaryngeal or endoscopic technique. The most commonly practiced techniques are supraglottoplasty, arytenoidoplasty, epiglottectomy, epiglottopexy which can be done by using cold instruments or laser [4].Aryepiglottoplasty is a variation of supraglottoplasty that involves incising the foreshortened aryepiglottic folds close to the base of the epiglottis. This allows the epiglottis to unfold which helps in widening the supraglotticairway [5]. Glossoepiglottopexy is a procedure where the mucosa of the lingual surface of the epiglottis and the corresponding mucosa of the base of tongue are removed with CO2 laser and then the epiglottis is sutured to the base tongue [6].The aim of this study is to understand the common presentations of severe laryngomalacia and its surgical outcome using microlaryngeal instruments by endoscopic technique.

2. Materials and Methods

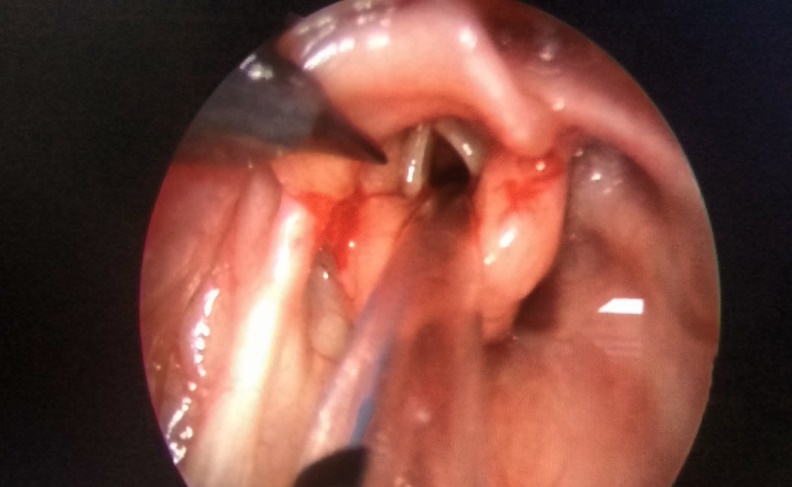

- This study is a prospective descriptive analysis of 10 patients who underwent endoscopic aryepiglottoplasty with glossoepiglottopexy at our pediatric tertiary care institution in pediatric ENT department for severe laryngomalacia over a period of five years between January 2012 and December 2016. Severity of laryngomalacia was diagnosed based on clinical presentation and endoscopic findings. Accordingly patients who presented with persistent stridor, intercostal and or xiphoidal retractions, feeding difficulty, failure to thrive and endoscopic findings including foreshortened aryepiglottic folds and posteriorly displaced epiglottis were included in the study. Patients with synchronous airway lesions like laryngeal web, severe trachea-bronchomalacia, vocal cord palsy and neurological abnormality like progressive neuropathy were excluded from the study. We studied variables deemed to have a potential influence on the outcome of aryepiglottoplasty with glossoepiglottopexy. These variables included general demographics (age at time of initial procedure, weight of the child at the time of the procedure, sex); medical comorbidities; additional upper airway procedures performed postoperatively. We also reviewed outcomes, including complications, the resolution of laryngomalacia, persistent laryngomalacia requiring other interventions including tracheostomy.Under general anaesthesia a direct rigid laryngoscope was introduced to focus the laryngeal inlet. An assistant surgeon held the 0 degree Hopkins rod endoscope which was connected to a camera and displayed on a monitor. The endoscopic picture gave a good magnified view of the laryngeal inlet. Assessment of the airway was done, including assessment of synchronous airway lesions. Once the diagnosis of laryngomalacia was made and the absence of synchronous airway lesions were confirmed then the patients underwent aryepiglottoplasty and glossoepiglttopexy usually as a second procedure. The parents were informed of the risks and benefits of the procedure and informed consent was obtained.Surgical techniqueUnder direct endoscopic visualization the arypeiglottic fold were cut with the microscissors bilaterally close to the lateral edge of epiglottis. Hemostasis was achieved by pressure application with an adrenaline soaked neurosurgical patty. Patients then underwent glossoepiglottopexy [Fig 1]. Glossoepiglottopexy was performed with a suction cautery to revitalize the base of the tongue and the lingual face of the epiglottis, and produce synechia [Fig 2]. Patients were then shifted intubated to the NICU or PICU based on the age of the patient. Postoperatively antibiotics and IV Dexamethasone 0.165 mg/ kg body weight was given for two days to reduce the postoperative edema. Feeds were started on the second postoperative day via nasogastric tube. If children tolerated nasogastric feeds, oral feeds were started on the third postoperative day. Extubation was planned 24 hours after the surgery in ICU. All the children were then closely monitored for relief of stridor, ease of feeding and weight gain at weekly intervals for 3 months.

| Figure 1. Showing aryepiglottoplasty |

| Figure 2. Showing epiglottopexy performed with suction cautery |

3. Results

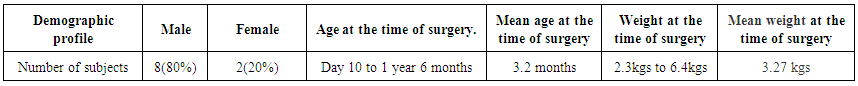

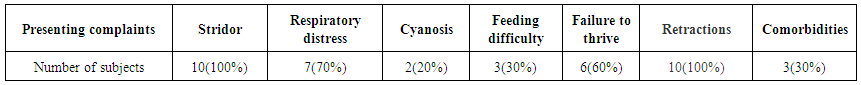

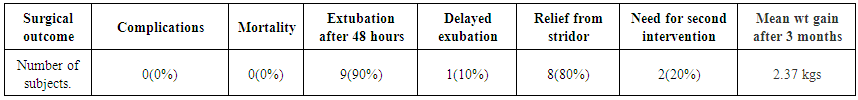

- A total of 10 patients were included in the study. Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the patient. There were 8 males and 2 females. Mean age at presentation was 4.2 months. Mean weight at presentation was 3.27 kgs.Table 2 shows the presenting complaints of the patients. All the 10(100%) of patients presented with stridor and chest retractions. Feeding difficulty was experienced in 3(30%) of patients. Failure to thrive was seen in 6(60%) of patients. Respiratory distress was observed in 7(70%) of the patients. Only 2(20%) of patients presented with cyanosis. There were 3 patients with co morbidities, one patient had co existent grade 1 subglottic stenosis and another had lymphangioma of the right side of the neck which wasn’t compressing the airway. One neonate had recovered from a MRSA positive pneumonia.Table 3 demonstrates the surgical outcome in our study. There were no complications like bleeding, aspiration or supraglottic stenosis in our study. There was no mortality in our study. All the 10 patients were extubated after 24hrs in the ICU. One patient underwent a tracheostomy as he developed respiratory distress after 15 days following a bout of URTI. Another patient who had a lymphangioma continued to have retractions and underwent tracheostomy and intralesional bleomycin injection.

| Table 1. Showing the demographic profile |

| Table 2. Showing the presenting complaints |

| Table 3. Showing the surgical outcome |

4. Discussion

- Laryngomalacia is widely regarded to be the most common cause of congenital infantile stridor, constituting 60% to 75% of the cases. [2] The vast majority of cases of laryngomalacia are considered benign, without any need for surgical intervention. Complete resolution of symptoms during early childhood, usually by 2 years of age [2]. However, 10% to 15% of the cases are considered severe enough to require surgical intervention, owing to serious complications such as upper airway obstruction, corpulmonale, and failure to thrive [7].Supraglottoplasty is the mainstay of surgical treatment for severe laryngomalacia. Supraglottoplasty can be further subdivided according to the anatomic region addressed. Incising the arypeiglottic fold mucosa is aryepiglottoplatsy. When the supraarytenoid tissue is resected it is called arytenoidoplasty. Glossoepiglottopexy refers to the attachment of the lingual surface of the epiglottis to the base tongue. These procedures can be performed using cold steel instruments or lasers.In our study there were 80% males and 20% females with severe laryngomalacia. 100% of our patients had stridor and chest retractions at presentation. Co-morbidity was found in 3((30%) of our patients. According to Heijden et al [8] comorbidity in their study population was 67%. According to their study comorbidity was related to more severe form of laryngomalacia. But the comorbidity did not show any relationship with the performed procedure. Synchronous airway lesions were found in 1 patient (10%) in our study. Heijden et al [8] reported SAL‘s in 40% of their cases. According to Heijden et al presence of SAL necessitated a significantly longer time for complete improvement.Most studies recommend using flexible fibreoptic endoscopy under general anaesthesia for confirming the diagnosis. We found that the technique using exposure of the larynx with intubating laryngoscope and visualization of the laryngeal collapse using rigid endoscope during spontaneous respiration under light general anesthesia is very practical. It allows good visualization of the larynx, sufficient time for the documentation of supraglottic folding, better control of the airway, and assessment of vocal cord mobility. In addition, the endoscope could be pushed distally to the subglottis and trachea to exclude any associated airway anomaly.We performed bilateral supraglottoplasty with 80% success rate with no complications. This in a contrast to a study by Reddy et al [9] who achieved a high success rate (95.7%), a low complication rate (8.5%), and observed the need for a contralateral procedure in 7(14.9%) of the 47 patients who underwent initial unilateral supraglottoplasty. Two patients who underwent initial bilateral supraglottoplasty developed supraglottic stenosis in their study.In our study 8 (80%) of our patient were relieved of their stridor, retractions and feeding difficulties. After a period of 3 months they demonstrated a mean weight gain of 2.37 kgs. Similar results were reported by Denoyelle et al [10]. They reported a success rate of 79%. In our study failure or partial improvement was seen in 2(20%) of patients. Failures were managed by tracheostomy alone in one case and tracheostomy with intralesional bleomycin in the other, as the patient had a lymphangioma of the neck. This is in contrast to a study by Heijden et al [8] who managed their failures by revision supraglottoplasty.There were no complications in our study during the procedure or post operatively. Fattah et al [11] reported complications in 7.4% of their patients. These included intraoperative bleeding, transient aspiration and supraglottic stenosis.Some of the studies have done unilateral aryepiglottolasty to avoid complications, our study we have done bilateral aryepiglottoplasty without any complications. Most studies use laser for epiglottopexy, our study used simple cautery without any complications giving good results.

5. Conclusions

- Laryngomalaciais the most common congenital anomaly of the larynx. Only 10% of patients present with severe laryngomalaciarequire surgical intervention. Our study shows that the simple procedure of aryepiglottoplasty with glossoepiglottopexy using regular microsurgical instruments like microscissors and suction cautery gives satisfactory results. All the patients underwent bilateral aryepiglottoplasty with glossoepiglottopexy without any complications like bleeding, aspiration and supraglottic stenosis. Hence we conclude that aryepiglottoplasty with glossoepiglottopexy is a cost effective and safe procedure.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML