-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Otolaryngology

p-ISSN: 2326-1307 e-ISSN: 2326-1323

2015; 4(3): 40-43

doi:10.5923/j.otolaryn.20150403.03

Cholesteatoma of the Concha Bullosa: Case Series and Review of Literature

Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Maliyappanahalli Siddappa Vijayashree

Otorhinolaryngology Department, Bangalore Medical College & Research Institute, Bangalore, India

Correspondence to: Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Otorhinolaryngology Department, Bangalore Medical College & Research Institute, Bangalore, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Cholesteatoma was first described in the ear and it is a common disease in the middle ear cavity. Cholesteatoma is rarely seen in the nose and paranasal sinuses. There are only two reported cases of cholesteatoma in the concha bullosa. In this article, the author describes three cases of cholesteatoma of the concha bullosa along with the review of literature.

Keywords: Concha bullosa, Cholesteatoma

Cite this paper: Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Maliyappanahalli Siddappa Vijayashree, Cholesteatoma of the Concha Bullosa: Case Series and Review of Literature, Research in Otolaryngology, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2015, pp. 40-43. doi: 10.5923/j.otolaryn.20150403.03.

1. Introduction

- Cholesteatoma is a relatively common disease within the middle ear cavity, but rarely does it manifest in the paranasal sinuses [1]. Cholesteatoma of the paranasal sinuses occurs when the normal respiratory epithelium that lines the sinus is partially or totally replaced by hyperkeratotic squamous epithelium, which in turn leads to formation of lamellar sheets of keratin-that is, a cholesteatoma. In the paranasal sinuses, cholesteatoma-which is also known as keratoma, primary epidermoid tumor, epidermoid cyst is rare [2].Cholesteatomas can arise in the skin, breast, kidney, central nervous system, and the cranium. Cranial sites include the temporal bone, orbit, mandible and, in rare cases, the paranasal sinuses. [2, 3-9]. When paranasal sinus involvement has occurred, the most common sites of origin have been the frontal sinus and the ethmoid sinus [6].Concha bullosa is the pneumatization of the middle turbinate and is one of the most common variations of the sinonasal anatomy. The incidence of concha bullosa was found to be 14% to 53.6%, as reported by various studies. There are only two published case of cholesteatoma inside the concha bullosa in the English language literature. [1].

2. Case 1

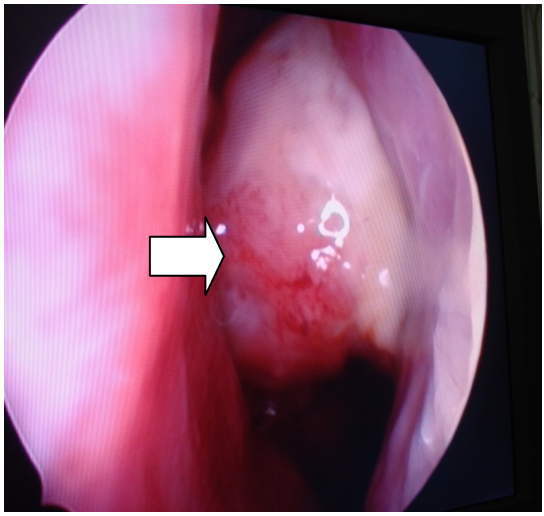

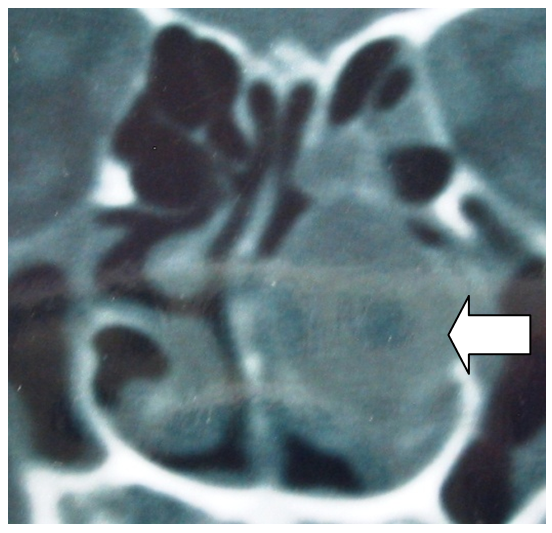

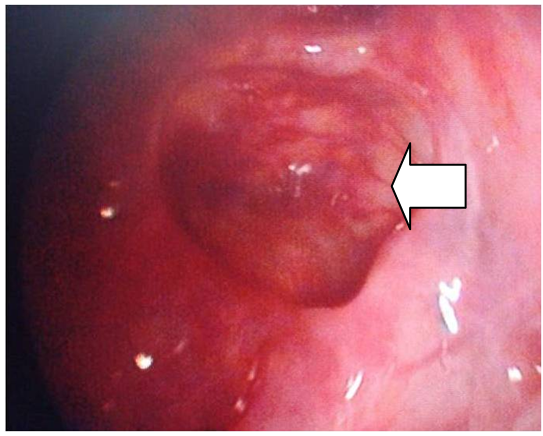

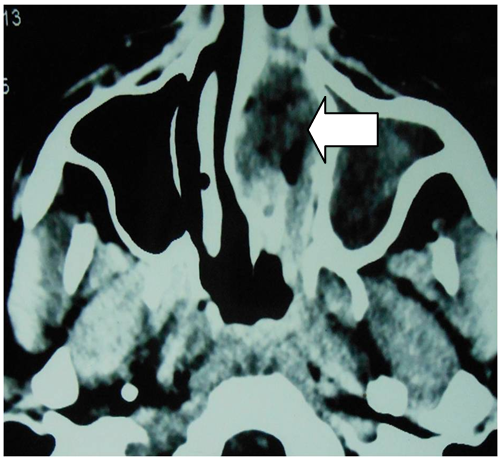

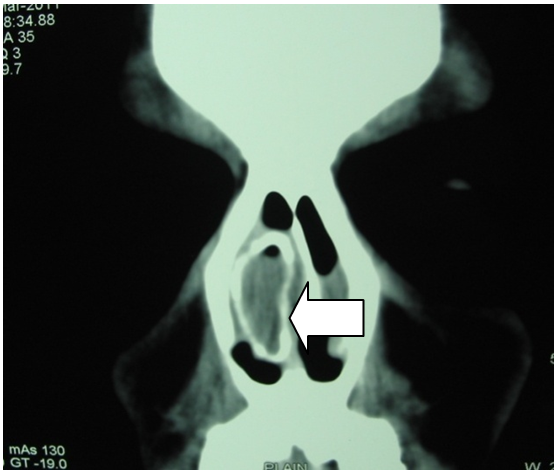

- An 18 year old female patient presented with complaints of unilateral gradually increasing left sided nasal obstruction of one year duration. Initially nasal obstruction was partial and later it progressed to complete nasal obstruction. She noticed a mass in the left nasal cavity 3 months ago. It was not associated with fever, headache or nasal discharge.Anterior rhinoscopy showed a bony hard swelling in the region of the middle turbinate and surface over the swelling was intact. Rest of the otorhinolaryngological examination was normal. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy showed enlarged middle turbinate [fig 1]. CT scan showed a bony cystic swelling in the region of the left middle turbinate. It was not enhancing on contrast administration [figure -2].

| Figure 1. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy showing (arrow) enlarged left middle turbinate |

| Figure 2. CT scan showed a bony cystic swelling (arrow) in the region of the left middle turbinate |

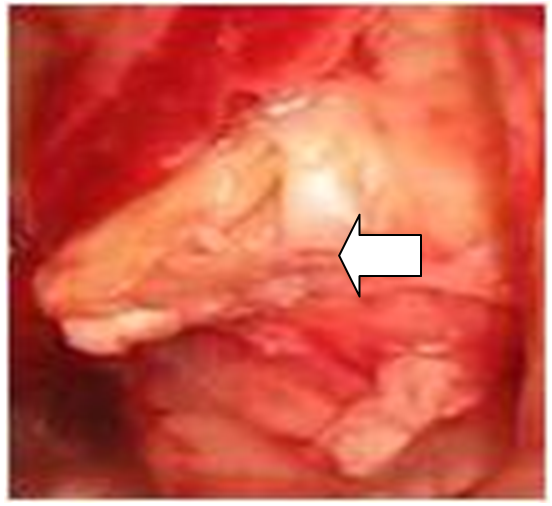

| Figure 3. Intraoperative picture showing (arrow) whitish yellow mass in the cyst |

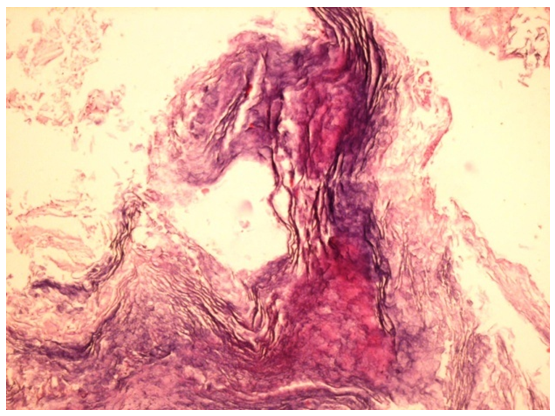

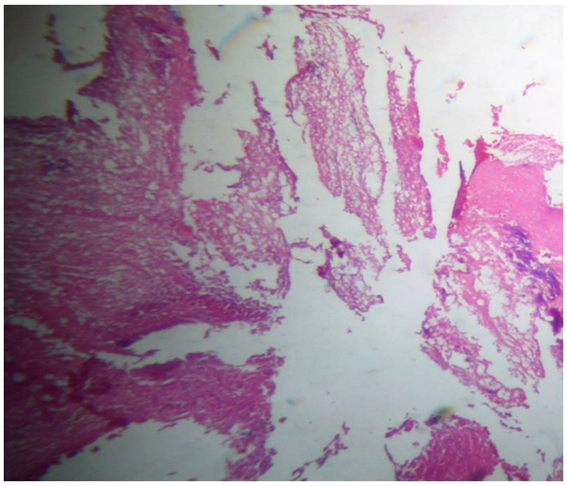

| Figure 4. Photomicrograph showing the stratified columnar epithelium with lamellar sheets of keratin |

| Figure 5. Nasal endoscopic picture showing (arrow) post-operative cavity |

3. Case 2

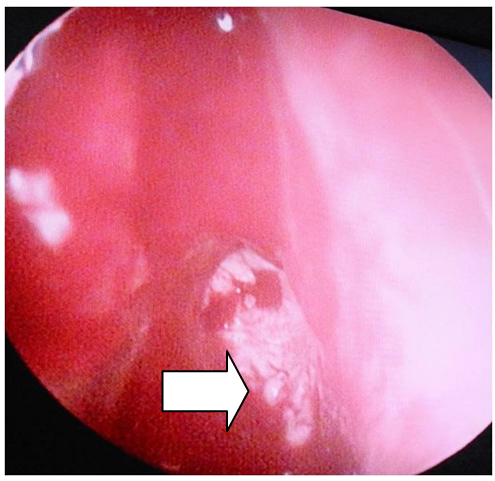

- A 32 year old male patient presented with unilateral left sided nasal obstruction and recurrent attacks of foul smelling nasal discharge of 6 months duration. Initially patient had partial nasal obstruction and later patient also had recurrent episodes of small quantity of foul smelling nasal discharge from the left nasal cavity. Anterior rhinoscopy showed a swelling in the region of the left middle meatus and there was mucopurulent discharge. Diagnostic endoscopy showed enlarged middle turbinate and there was an opening over the anterior surface of the turbinate through which there was a mucopurulent discharge [figure 6]. CT scan showed a bony cystic swelling in the region of the middle turbinate [figure 7].

| Figure 6. Endoscopy showing (arrow) enlarged middle turbinate and an opening over the anterior surface of the turbinate |

| Figure 7. CT scan showing a bony cystic swelling (arrow) in the region of the left middle turbinate |

| Figure 8. Photomicrograph showing the stratified columnar epithelium with lamellar sheets of keratin |

4. Case 3

- An eighteen year old male patient presented with complaints of right sided nasal obstruction for the past six months. Anterior rhinoscopy showed enlarged right middle turbinate. Rest of the otorhinolaryngological examination was normal. Diagnostic nasal endoscopy showed enlarged right middle turbinate [fig 9]. CT scan showed a bony cystic swelling in the region of the right middle turbinate.

| Figure 9. CT scan showing (arrow) a bony cystic swelling in the region of the right middle turbinate |

5. Discussion

- Cholesteatoma of the paranasal sinuses occurs when the normal respiratory epithelium is replaced by hyperkeratotic squamous epithelium. This results in the formation of a matrix of lamellar sheets of keratin that eventually becomes a mass in a confined space [2, 4, 5, 8].Pathogenesis:Cholesteatoma is mainly classified into congenital and acquired types. Four basic theories have been proposed to explain its development and in 2007 a new fifth theory was proposed.• Remark and Bucy’s theory of congenital epithelial rests (1854). The most widely accepted theory is the congenital cholesteatoma theory. This theory was proposed by Remark" and Bucy'. They believe that cholesteatomas arise from misplaced epithelial rests that develop during the embryonic stage [10, 11]. Congenital (primary) cholesteatoma is believed to be a result of misplaced ectodermal, epithelial cell remnants during the formation of the face in the third to fifth week of embryogenesis [12].• Wendt’s metaplasia theory (1873). This theory was proposed by Wendt. According to this theory non-keratinizing squamous epithelium that lines a cavity undergoes a metaplastic change, possibly in response to infection, and it begins to produce keratin [13].The metaplasia theory has been rejected by many authors because squamous epithelium deriving from metaplasia due to chronic rhinosinusitis is of a non-keratinizing type [9].• Habermann’s immigration theory (1888). Habermann theorized that cholesteatoma is caused by the migration of keratinizing squamous epithelium into an area where it is not usually found [14].This theory cannot be accepted for sinonasal cholesteatoma. Immigration of epithelium from the nasal vestibule to the intranasal region has never been reported and we also could not show such an intranasal tract in our case [9].• Ewing’s implantation theory (1928).This theory was proposed by Ewing. He proposed that cholesteatomas arise secondary to the direct entry of epithelium during trauma [15]. Indeed, cholesteatomas have been reported to occur at the site of a previous injury and after nasal or sinus surgery and ear surgery. The epithelium continues to desquamate and form an expanding, destructive cyst [16, 17]. The implantation theory cannot be accepted because none of our patients had any previous history trauma or surgery to the head and neck region.• Gordon’s fistula theory (2007).This theory was proposed by Gordon [18]. He proposed that sinus cholesteatomas arise secondary to long standing small fistulas. He suggested that there is link between fistulas and cholesteatomas, and cholesteatoma is a result of misdirected attempt to seal off a fistulous tract.Macroscopically, cholesteatomas appear as cyst-like structures. Microscopically, cholesteatoma capsules exhibit fully differentiated, stratified squamous epithelium on connective tissue. The central core of a cholesteatoma is made up of anucleate keratin squamae. The subepithelial connective tissue is of varying thickness, and it contains inflammatory infiltrate and fibroblasts [19].Cholesteatoma are not biologically neoplastic. They have the capacity to erode bone and expand into adjacent areas. The capacity to erode bone has been attributed to enzymes [4, 20, 21]. The clinical presentation and radiologic characteristics of maxillary sinus cholesteatoma are difficult to distinguish from those of malignancy [22].The treatment for sinonasal cholesteatoma is surgical excision. Cholesteatoma mass should be removed completely to prevent the recurrence [2, 16, 22]. In our patients cholesteatoma was removed completely through transnasal endoscopic approach. Patients were followed for a minimum period of six months and there was no recurrence.Though the sinonasal cholesteatoma are rare, they can present with the clinical features suggestive of malignancy. An otolaryngologist should be familiar with this rare clinical entity.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML