-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Otolaryngology

p-ISSN: 2326-1307 e-ISSN: 2326-1323

2014; 3(2): 29-35

doi:10.5923/j.otolaryn.20140302.04

Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Complicated Cholesteatomatous Ear Disease

Borlingegowda Viswanatha1, Khaja Naseeruddin2, Rasika Ravikumar1, Maliyappanahalli Siddappa Vijaya1, Nisha Krishna1

1Bangalore medical college & research institute

2Former Director, Vijayanagr institute of medical sciences, Bellary

Correspondence to: Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Bangalore medical college & research institute.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

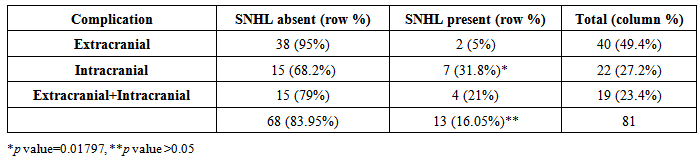

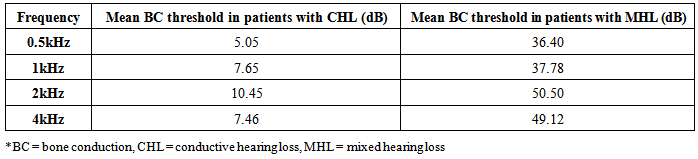

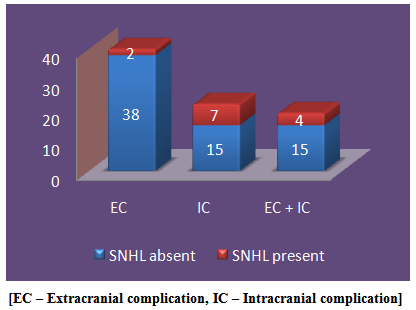

Otitis media is one of the most commonly treated infections in clinical practice today. The majority of patients with otitis media do well with or without antimicrobial therapy. However, there is a subset of patients who develop serious complications from this otherwise self-limiting disease. In the pre antibiotic era, acute otitis media used to be the main trigger for the complications. With the advent of good antibiotics, this has drastically reduced and now most of the complications arise due to chronic otitis media (COM). Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) as a complication of COM is now well proven. The cochlear function may be affected by the bacterial toxins percolating through the round window and reaching the inner ear or by the use of topical or systemic ototoxic drugs or by the direct invasion of the inner ear by the pathogenic organism and consequent inflammatory response. Likewise the pattern of hearing loss in COM has been often studied. The incidence in the previous studies of sensorineural hearing loss ranges from 13% to 24% and includes both mucosal and squamous varieties with some studies showing significant difference between the two varieties while others showed no difference. Complications can occur in the acute exacerbation of an infection or as a result of bony destruction from chronic bioenzymatic activity (i.e. in cholesteatoma). The incidence of SNHL in complicated otitis media despite the absence of labyrinthitis has not been reported in literature. We are presenting the first research work on sensorineural hearing loss in exclusively complicated cholesteatomatous ear disease. Aims & Objectives: The aim of our study was to know the pattern of hearing loss, especially the occurrence of sensorineural hearing loss, in complicated cholesteatomatous ear diseases and to identify the factors influencing it. Material & Methods: All the patients of squamous epithelial otitis media with extracranial or intracranial complications who presented to us during the study period and who met our inclusion criteria were included in the study. After cleaning the ear off discharge, pure tone audiometry was done and the findings were recorded. Results: Sensorineural component of hearing loss was present in 5% of patients with extracranial complications (all of whom had labyrinthine fistula), 31.8% in patients with intracranial complications and 21% in patients with both extracranial and intracranial complications. Overall, out of 81 patients, 16.05% had sensorineural component of hearing loss. This was comparable to earlier studies on SNHL in uncomplicated COM (p>0.05). The patients with intracranial complication had a significant higher risk of developing SNHL (p=0.01797). The average bone conduction threshold across the frequencies of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 kHz was 43.45dB (standard deviation of 5.67). Tinnitus was present only in patients with sensorineural component of hearing loss and was present in all 13 of them. Conclusions: Sensorineural hearing loss occurs much more commonly when a patient develops intracranial complication. Extracranial complications do not increase the chances of developing SNHL. Though labyrinthine fistula is the most common extracranial complication causing SNHL, not all patients with labyrinthine fistula develop SNHL. Meningitis is the most common intracranial complication associated with SNHL and is always associated with it. The incidence in fact falls further when both extracranial and intracranial complications are present than intracranial complication alone. Tinnitus is the classical symptom which should raise the suspicion of Sensorineural hearing loss in the patient.

Keywords: Sensorineural hearing loss, Complications, Cholesteatoma

Cite this paper: Borlingegowda Viswanatha, Khaja Naseeruddin, Rasika Ravikumar, Maliyappanahalli Siddappa Vijaya, Nisha Krishna, Sensorineural Hearing Loss in Complicated Cholesteatomatous Ear Disease, Research in Otolaryngology, Vol. 3 No. 2, 2014, pp. 29-35. doi: 10.5923/j.otolaryn.20140302.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The diagnosis of chronic otitis media (COM) implies a permanent abnormality of the pars tensa or flaccida, most likely a result of earlier acute otitis media, negative middle ear pressure or otitis media with effusion. COM equates with the classic term chronic 'suppurative' otitis media that is no longer advocated as COM is not necessarily a result of 'the gathering of pus'. However, the distinction remains between active COM, where there is inflammation and the production of pus, and inactive COM, where this is not the case though there is the potential for the ear to become active at some time. A third clinical entity is healed COM where there are permanent abnormalities of the pars tensa, but the ear does not have the propensity to become active because the pars tensa is intact and there are no significant retractions of the pars tensa or flaccida. 'Healed COM' can also be the end result of successful surgery. COM has also been classified into Mucosal COM and Squamous COM (cholesteatoma) depending on the pathology in the middle ear [1].The middle ear couples sound signals from the ear canal to the cochlea primarily through the action of the tympanic membrane and the ossicular chain. Hence, hearing loss is the natural sequelae of chronic otitis media. 80% of adults with COM present with hearing impairment [1]. As middle ear and tympanic membrane participate in the conduction of sound from external ear to inner ear and help in impedance matching, the most common type of hearing loss in chronic otitis media is conductive hearing loss.Conductive hearing loss in chronic otitis media occurs due to the following reasons [2].1. Perforation of tympanic membrane2. Erosion of ossicular chain, most commonly long process of Incus and stapes suprastructure leading to ossicular discontinuity3. Significant granulation tissue around the ossicular chain reducing its mobility4. Presence of mucus or pus, adhesions and tympanosclerosis causing ossicular fixationThough the classic type of hearing loss described for COM is conductive, several investigators have reported sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) do occur concomitantly or as sequelae of COM, despite the absence of symptoms of labyrinthitis. The SNHL has been ascribed to 1. Contribution of the middle ear and ossicles to hearing mechanism by bone conduction (Carhart effect) 2. Cochlear dysfunction resulting from extension of inflammation in the middle ear cleft through the round window (RW) membrane [2].3. Use of ototoxic ear drops in non-intact tympanic membrane or use of systemic ototoxic drugs. Paparella et al (1984) hypothesized that COM can cause temporary or permanent threshold shifts by passage of inflammatory agents through the RW which can spread apically and become measurable on routine audiometry. According to them, temporary threshold shifts occurred from serous labyrinthitis while permanent threshold shifts occurred from permanent dysfunction of organ of Corti. They showed that the anatomical characteristics of the RW are such that it encourages the accumulation, stagnation and absorption of purulent secretions into the perilymph.The RW membrane has 3 layers which together measures approximately 0.065mm. The RW niche is approximately 1 mm in depth and 2 mm in diameter. There are essentially no ciliated cells in the region of the RW under normal circumstances. Thus pus gets pooled in the adjacent snus tympani space, especially when the patient is in upright position. Remnants of mesenchyme in the RW niche and sinus tympani are also slow to be resorbed. These factors encourage pus or infected tissue to be concentrated at the RW thereby encouraging absorption through the RW membrane leading to chemical contamination of the perilymph [3].Vartiainen and Karjalainen reported that SNHL occurs in 18% of chronically infected ears but in only 1.6% of control ears. In their subjects, SNHL was significantly more frequent in ears with prolonged periods of discharge and with cholesteatoma [4].Azevedo et al. in their study found that in the ear with chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM), the frequency of SNHL was 13% [5].In all the previous studies, deterioration in bone conduction was used as the measurement of inner ear changes. To find out the pathological basis of inner ear affection Cureoglu et al. in 2004 studied 15 human temporal bones with unilateral COM and compared with opposite normal temporal bones. Loss of hair cells was common in basal turn of cochlea and there was also significant reduction in the area of stria vascularis and spiral ligament compared to normal side [6].Loss of outer hair cells (OHCs) and inner hair cells (IHCs) in the cochlear base and other pathological changes in the inner ear have been reported in experimental otitis media in animals and also in the affected ear in human temporal bones of patients with unilateral chronic otitis media. Passage of toxic substances through the RW membrane can cause perilymphatic inflammation starting in the cochlear basal turn, which can spread apically resulting in auditory threshold shifts at lower frequencies. [7]Although various authors have presented the audiological implications of inner ear involvement in otitis media, the exact effects of otitis media on the cochlear pathology and function in humans are not clearly understood. More so, there is no literature available on the pattern of hearing loss in squamous COM (cholesteatoma) with extracranial/ intracranial complications. Hence, the purpose of our study was to determine the pattern of hearing loss in complicated cholesteatomous ear disease and to identify the factors influencing it.

2. Materials and Methods

- This study was carried out in Sri Venkateshwara ENT Institute, Victoria hospital, a tertiary care hospital in Bangalore during the period January 2008 to 2013. Overall 81 patients, diagnosed to have chronic otitis media with extracranial or intracranial complications were included in the study. As some had bilateral ear discharge, the study had 100 discharging ears. Written informed consent was taken from all patients included in the study.Inclusion Criteria: 1. Patients presenting with chronic ear discharge for more than 6-12 weeks.2. Patients with cholesteatoma formation on clinical examination, confirmed by otomicroscopy and radiological examination.3. Patients with extracranial or intracranial complications of COM (mastoiditis, petrositis, facial nerve paralysis, Labyrinthine fistula, post auricular abscess or fistula, meningitis, lateral sinus thromblophlebitis, brain abscesses, otitic hydrocephalus etc).Exclusion Criteria:1. Patients without any written informed consent.2. Patients with other serious medical conditions such as immunodeficiency states, Hypertension, malignancy and history of cerebrovascular accidents.3. Patients with mucosal chronic otitis media and patients with inactive retraction pockets without cholesteatoma.4. Patients with history of previous surgery in the complaining ear.5. Patients with history of chronic noise exposure or previous head injury.6. Patients with clinical features suggestive of labyrinthitis.7. Patients with history of use of ototoxic ear drops (though some of the patients did use topical ear drops, the drug used was proven to have no ototoxic effects)All the patients who met the inclusion criteria, were subjected to pure tone audiometry after cleaning the ear off discharge and the findings were recorded. Patients with air-bone gap of >10dB and bone conduction threshold <25 dB were labelled to have conductive hearing loss. Sensorineural hearing loss (after eliminating the Carhart effect) was considered when the bone conduction threshold was > 25dB. Patients with both >10 dB air-bone gap and bone conduction threshold >25 dB were classified as mixed hearing loss. Ear discharge was also sent for pus for culture and sensitivity and the results were recorded. Patients with intracranial complications underwent ear surgery only after neurosurgical clearance and after the general condition of the patient improved to acceptable standards for fitness for surgery.

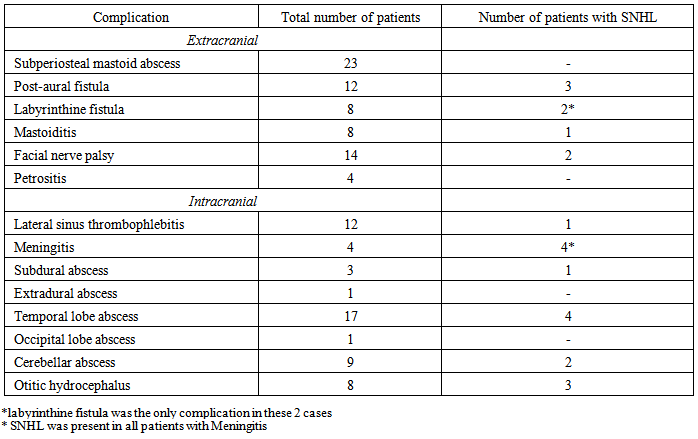

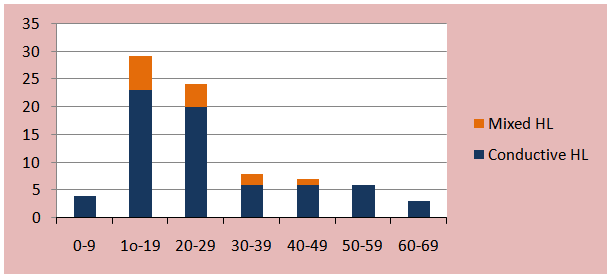

3. Observation and Results

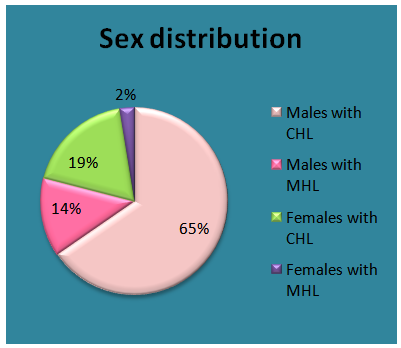

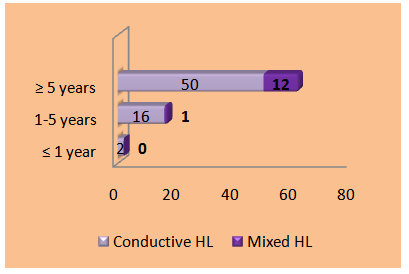

- A total of 81 patients with complications of COM were included in our study. 71 of them had unilateral squamous disease (9 of them had mucosal disease in the opposite ear) while 10 had bilateral squamous disease. The age of the patients ranged from 5 years to 65 years and majority(65.4%) of them belonged to the younger age group between 10 to 30 years of age (Figure 1). 64 of the patients were males with only 17 females in the study group (male: female ratio of 3.76:1) (Figure 2). The socio economic status of the patients was either lower class (42 patients) or middle class (39 patients).

| Figure 1. Showing pattern of hearing loss in comparison with the age group |

| Figure 2. Showing sex distribution |

| Figure 3. Duration of discharge & hearing loss |

| Figure 4. Showing distribution of extracranial complication, intracranial complication |

|

|

|

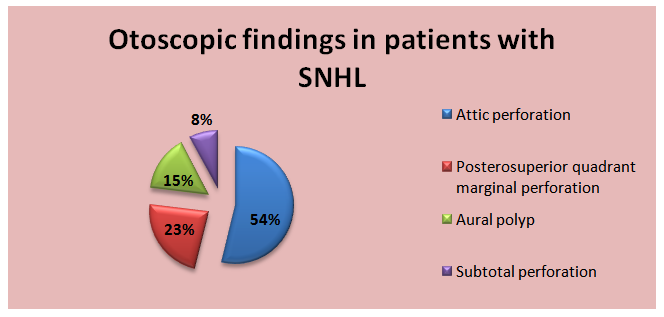

| Figure 5. Showing otoscopic findings in patients with sensorineural hearing loss |

4. Discussion

- Hearing loss associated with CSOM is a matter of concern globally, particularly in children because of its long term effect on development of essential skill in speech, language and social interaction. Hearing disability in adults also has its bearing on the individual and on the society. [6]Conventionally, hearing loss described in CSOM is a conductive hearing loss. But, it has been observed that some patients display an added sensorineural component to their conductive hearing loss. The SNHL has been ascribed due to contribution of the middle ear hearing mechanism by bone conduction (Carhart effect) and/or cochlear dysfunction resulting from extension of inflammation in the middle ear cleft through the round window membrane [2].The middle–inner ear interaction that occurs in otitis media has been an area of interest for many researchers. Joglekar et al observed that children who have recovered from otitis media have significantly poorer hearing in extended high frequencies as compared with their counterparts without otitis media. Pathological changes in temporal bones and high frequency SNHL in animals and patients with otitis media suggest preferential involvement of the cochlear basal turn. Many experimental data suggest that bacterial components and inflammatory mediators produced in the middle ear pass through the round window membrane into the inner ear, altering expression of other proteins, including K+, Na+, and other ion channels and transporters localized in the stria vascularis and spiral ligament, resulting in disturbance of ion homeostasis, which in turn can cause injury of various types of cochlear cells, including hair cells, and result in SNHL [7].In a study by Joglekar et al [7], about 19% of temporal bones with chronic otitis media and about 9% with purulent otitis media had inflammatory changes of the round window membranes, with inflammation of the adjacent scala tympani and pathology of the basal turns of the cochlea. They found that significant loss of outer hair cells or inner hair cells and decrease in area of stria vascularis in the basal turn of affected temporal bones as compared to age-matched controls are results of labyrinthine pathological changes secondary to otitis media.In our study, SNHL was seen more commonly in men and in the age group 10 to 30 years. This may be because 65.4% of our entire study group were between 10 to 30 years and majority of them were males. Thus, there is no significant difference in the age group and gender between patients with CHL and Mixed hearing loss.Hearing loss in COM depends on the duration of the disease and socioeconomic condition. A comparative study of prevalence of COM between lower and higher socio-economic groups showed that prevalence of COM in low socioeconomic group was 9.4%, where as in elite group it was only 0.67% and among the COM cases, 65.52% were aware while 34.48% were not aware about their disease and sequelae of COM [8]. It is likely that SNHL associated with CSOM is higher in populations of lower socioeconomic status. This may be corroborated by hypothesis that there is a difficulty to access treatment with antibiotics, inadequate follow up and poor hygiene and education in the lower socioeconomic group [5]. In our study, 51.8% of the patients belonged to lower class while the rest were from middle class. This was reflected in the subset of patients with SNHL as 7 out of 13 were from lower class and the rest 6 from middle class. In a study, among 195 patients with unilateral COM, disease duration showed significant influence upon SNHL and an average increase of 5.5 dB for every 10 years was found by Cusimano et al [6]. In our study, 12 out of 13 (92.3%) patients with SNHL had duration of discharge and hearing loss for more than 5years. This was comparable to the previous studies. [4]The average bone conduction threshold in patients with SNHL in our study was 43.45dB (standard deviation of 5.67). This was higher than the bone conduction of SNHL in COM without complications in previous studies which ranged from 25 to 40 dB with few outliers above 40dB [8, 9, 10]. 16.05% of our patients with complicated COM developed SNHL in addition to CHL (mixed hearing loss). This was comparable to the incidence of SNHL in COM without complications according to other studies [2 ,6, 8, 9]. There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of SNHL with the development of complications (p value > 0.05). Thus the presence of complications though does not increase the occurrence of SNHL but definitely increases the bone conduction threshold among the patients who develop SNHL.Intragroup comparison among patients of COM with complications showed that presence of intracranial complication significantly increased the incidence of SNHL (p = 0.01797). Thus patients with intracranial complication have a significant higher risk of developing SNHL than extracranial complications or both. Possible factors leading to SNHL in intracranial complications of CSOM may be inflammation of meninges or involvement of the auditory cortex. However further research is required in this area.

5. Limitations of Our Study

- As no previous literature was available on the pattern of hearing loss in patients of COM with complications, our study was the first of its kind and needs further validation by a comparative study with age and gender matched controls. Also pre operative and post operative comparison will throw light on the reversibility of the SNHL.

6. Conclusions

- Sensorineural hearing loss has little influence by age, gender and socioeconomic status. But is significantly influenced by the duration of disease, longer durations (>5years) increasing the likelihood of developing SNHL. The presence of complications though does not increase the occurrence of SNHL but definitely increases the bone conduction threshold among the patients who develop Sensorineural hearing loss. SNHL occurs much more commonly when a patient develops intracranial complication. Extracranial complications do not increase the chances of developing SNHL. Though labyrinthine fistula is the most common extracranial complication causing SNHL, not all patients with labyrinthine fistula develop SNHL. Meningitis is the most common intracranial complication associated with SNHL and is always associated with it. The incidence in fact falls further when both extracranial and intracranial complications are present than intracranial complication alone. Tinnitus is the classical symptom which should raise the suspicion of Sensorineural hearing loss in the patient. To best of our knowledge this is the first research work on sensorineural hearing loss in exclusively complicated cholesteatomatous ear disease.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML