-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Optics and Applications

p-ISSN: 2168-5053 e-ISSN: 2168-5061

2014; 4(4): 101-109

doi:10.5923/j.optics.20140404.01

Optimalization of Cross- and Direct- Type of Fiber Optic Ring Resonator (FORR) with Coupling Coefficient (κ) Variation

Sasono Rahardjo, Purnomo Sidi Priambodo, Djoko Hartanto, Harry Sudibyo

Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Indonesia, Depok, 16424, Indonesia

Correspondence to: Sasono Rahardjo, Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Indonesia, Depok, 16424, Indonesia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

We investigate a single ring Fiber Optic Ring Resonator (FORR) with single coupler, has cross- and direct type configuration. These configurations depends on the structure of coupling waveguide inside the coupler. Both configurations are formulated regarding to output and loop intensities when power coupling coefficient, κ, varries from 0.01 to 0.99. Analytical result shows Cross type FORR (CFORR) has opposite behavior to that of Direct type FORR (DFORR). The higher κ is, the output intensity at resonance of CFORR decreases and reaches its minimum at κ = 0.93 and further increases sharply. Whereas for DFORR, output intensity at resonance decreases sharply until reaches its minimum at κ= 0.07, and then increases again. Other main result is when κ is at around 0.5, both configurations show output intensities for almost the same value. These results update the analytical work reported previously by Seraji et al [29]. Analytical results given in this report are useful in the selection of the configuration of the FORR for certain applications, especially in the case of the use of nonlinear configuration FORR. An experimental result is reported as well to confirm the analytical result.

Keywords: Comparative analysis, Fiber optic ring resonator (FORR), Cross and direct type ring resonator

Cite this paper: Sasono Rahardjo, Purnomo Sidi Priambodo, Djoko Hartanto, Harry Sudibyo, Optimalization of Cross- and Direct- Type of Fiber Optic Ring Resonator (FORR) with Coupling Coefficient (κ) Variation, International Journal of Optics and Applications, Vol. 4 No. 4, 2014, pp. 101-109. doi: 10.5923/j.optics.20140404.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

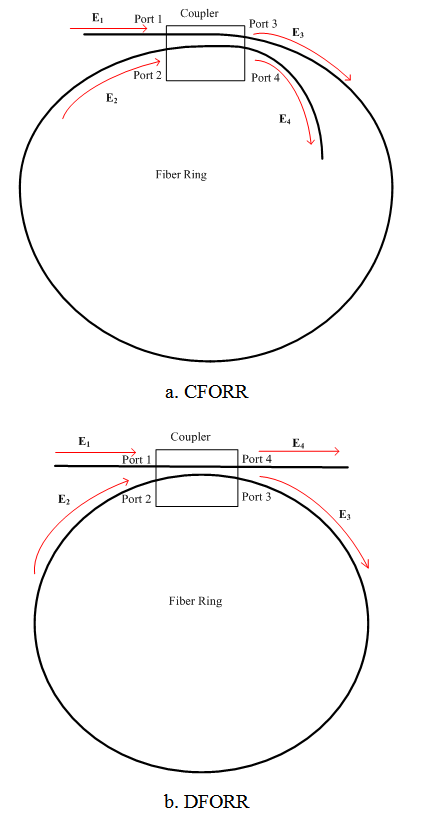

- Due to its high Finesse characteristic, Optic Ring Resonator (ORR) has become a main focus in optical device researches such as in wavelength selective switches [1], add-drop filters [2], biosensors [3], dynamic characteristics [4], single-frequency lasers [5], single and multi structures [6-11], multi inputs [12]. Many ORR researches utilized fiber to form the ring as Fiber ORR (FORR) and published their results on coherence effect [13], dynamic resonance characteristic [14], ringing phenomenon [15], bistability and instability [16], fiber bragg grating filter [17], simultaneous resonance with double couplers [18], optical vernier filter [19], transmission characteristics and sensitivity [20-21], erbium doped fiber ring laser [22] and for gyroscope aplication as well [23], temperature sensors and transducers [24], gas detection such as hydrogen sensor [25-27] and other optochemical sensors [29]. All of these show that FORR is still interesting research theme in the optical technology research, in addition to its simplicity to utilize it.In 1982, Stokes et al [16] presented their analytic research of FORR in which one fiber optic is formed a ring with parts closed each other as shown in Figure 1.a hereinafter referred to as Cross type FORR (CFORR). In his paper Stokes mentioned that the characteristics of output is change as the intensity loss,

varies, where the Finesse decreases as the intensity loss increases (

varies, where the Finesse decreases as the intensity loss increases ( =0.05, 0.10) [16]. However, Stokes did not make any characteristic change based on

=0.05, 0.10) [16]. However, Stokes did not make any characteristic change based on  variation.In 2012, Seraji et al. [29] used their own formulations and performed a comparison between cross- and direct coupled FORR as shown in Figure 1.b. He concluded that the Finesse of CFORR increases as

variation.In 2012, Seraji et al. [29] used their own formulations and performed a comparison between cross- and direct coupled FORR as shown in Figure 1.b. He concluded that the Finesse of CFORR increases as  increases (by varying

increases (by varying  = 0.35, 0.55, 0.75, 0.95), while for Direct type FORR (DFORR), the Finesse decreases as the

= 0.35, 0.55, 0.75, 0.95), while for Direct type FORR (DFORR), the Finesse decreases as the  increases (by varying

increases (by varying  = 0.05, 0.25, 0.45, 0.65). For more, he concluded that the loop intensity of cross type is nearly double of its direct type.In this paper, we conduct an analysis of the two configurations based on Stokes’ formula [16] and showing the characteristic intensities for both configurations, especially for the peaks and dips at resonance condition when

= 0.05, 0.25, 0.45, 0.65). For more, he concluded that the loop intensity of cross type is nearly double of its direct type.In this paper, we conduct an analysis of the two configurations based on Stokes’ formula [16] and showing the characteristic intensities for both configurations, especially for the peaks and dips at resonance condition when  varies (

varies ( = 0.01 until 0.99 with interval of 0.01). It is shown that their relations to

= 0.01 until 0.99 with interval of 0.01). It is shown that their relations to  is not linear, and they exhibit an opposite phenomena to each other. We explore further with an experiment utilizing Polarization Maintained Fiber (PMF) and show that DFORR shows better Finesse than that of CFORR, and will be published in a separate paper.

is not linear, and they exhibit an opposite phenomena to each other. We explore further with an experiment utilizing Polarization Maintained Fiber (PMF) and show that DFORR shows better Finesse than that of CFORR, and will be published in a separate paper. 2. CFORR and Its Response Formula

- To understand the working principles of FORR, we conduct simulation and experiment utilizing a 2x2 coupler (2 inputs and 2 outputs) to form a ring resonator as shown in Figure 1. Signal,

, passes into a single coupler with coupling ratio,

, passes into a single coupler with coupling ratio,  , the signal is split into 2 directional output within the coupler, a part of the signal is directed to the output port as

, the signal is split into 2 directional output within the coupler, a part of the signal is directed to the output port as  and the other part is directed into the loop and will be sent back to get through the coupler again. The form of waveguides inside the coupler are different where as Figure 1. a shows a cross type coupler and Figure 1b show a direct type one. This difference of structure, then, reflects the response formula as will be discussed below.

and the other part is directed into the loop and will be sent back to get through the coupler again. The form of waveguides inside the coupler are different where as Figure 1. a shows a cross type coupler and Figure 1b show a direct type one. This difference of structure, then, reflects the response formula as will be discussed below. | Figure 1. Schematic diagram of FORR with single coupler |

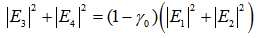

2.1. Intensities of Output and Loop for CFORR

- Cross type configuration is the beginning of the research associated with FORR, since it is easy to form a ring with only 1 single fiber and bring certain parts of each end of the fiber close to each other, as illustrated in Figure 1.a, thus the evanescent mode of the circulating light gets coupled to the nearby fiber optic.Directional coupler is modeled as an ideal device with no loss, but with an additional fractional intensity loss,

, that independent to coupling coefficient,

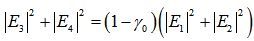

, that independent to coupling coefficient,  . Thus, under steady state operation, the relation of complex amplitude of electric fields of light at each port (port 1 ~ port 4) may be expressed as [16]:

. Thus, under steady state operation, the relation of complex amplitude of electric fields of light at each port (port 1 ~ port 4) may be expressed as [16]: | (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

| (2.3) |

is the amplitude of complex field at i-th port,

is the amplitude of complex field at i-th port,  is the power coupling coefficient of the coupler.

is the power coupling coefficient of the coupler.  = 0 when totally there is no coupling, and

= 0 when totally there is no coupling, and  =1 means perfect cross coupling occurs.

=1 means perfect cross coupling occurs.  and

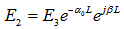

and  are then related through:

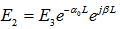

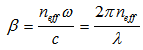

are then related through: | (2.4) |

,

,  is the amplitude attenuation coefficient of the fiber,

is the amplitude attenuation coefficient of the fiber,  is the effective refractive index of the fiber,

is the effective refractive index of the fiber,  is the optical frequency,

is the optical frequency,  is the speed of the light and

is the speed of the light and  is the fiber ring’s length. By utilizing equations (2.2), (2.3), (2.4), we may derive

is the fiber ring’s length. By utilizing equations (2.2), (2.3), (2.4), we may derive  at port 3 and

at port 3 and  at port 4 that contains

at port 4 that contains  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  as:

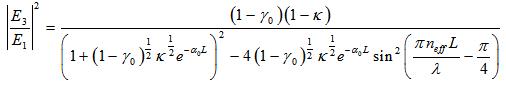

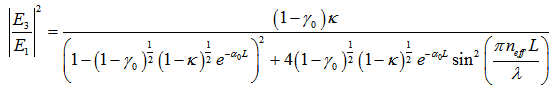

as: | (2.5) |

| (2.6) |

in Eq. (2.5) is known also as the normalized loop intensity,

in Eq. (2.5) is known also as the normalized loop intensity,  , of light entering into the ring resonator, while

, of light entering into the ring resonator, while  as in Eq. (2.6) is known as the normalized output intensity of the system. Then,

as in Eq. (2.6) is known as the normalized output intensity of the system. Then,  and

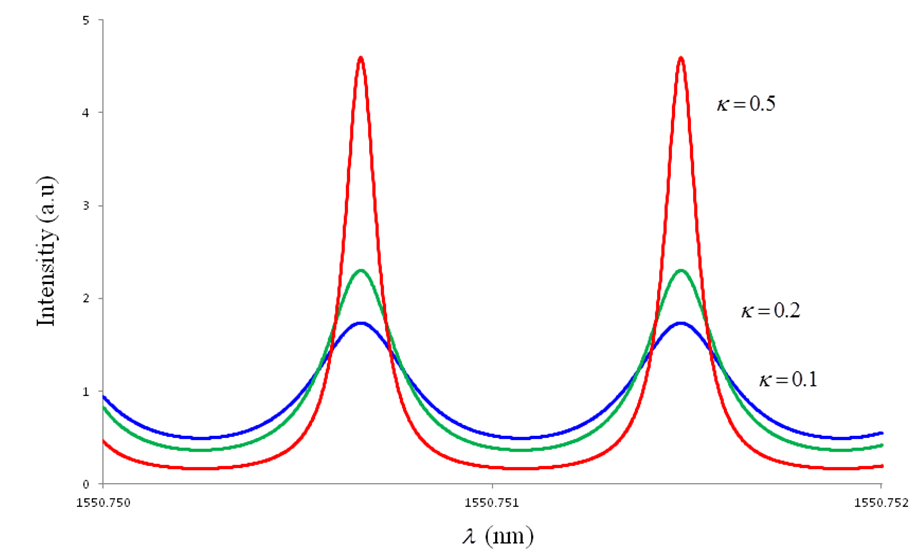

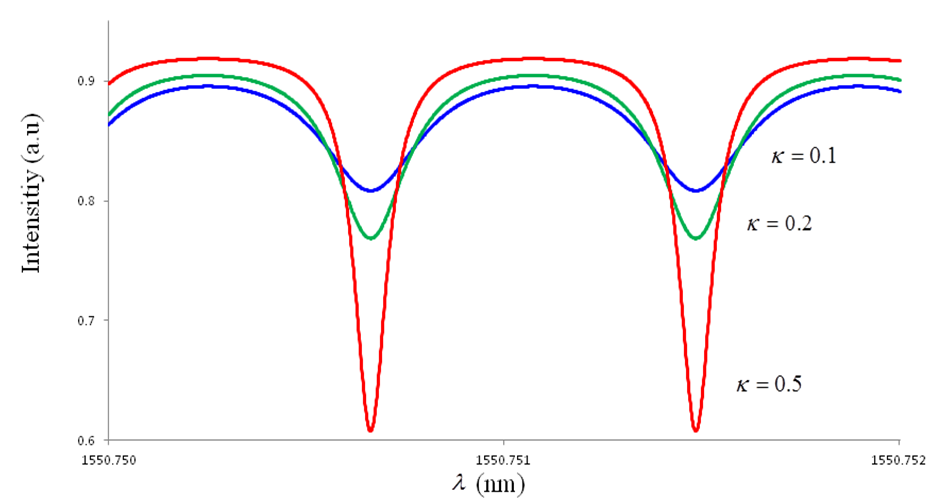

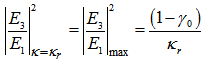

and  may be shown as in Figure 2 and 3 respectively, where we set

may be shown as in Figure 2 and 3 respectively, where we set  (typical value: 5% ~ 10%),

(typical value: 5% ~ 10%),  = 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5.

= 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5. | Figure 2.  Graph for CFORR Graph for CFORR |

| Figure 3.  Graph for CFORR Graph for CFORR |

2.2. Resonance Condition for CFORR

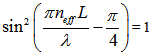

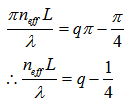

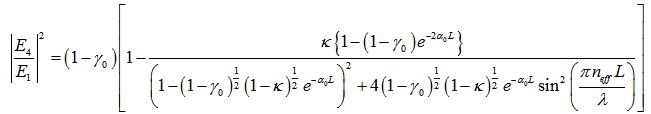

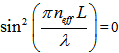

- The resonance condition of the configuration may be achieved when

becomes maximum and at the same time,

becomes maximum and at the same time,  is 0. The former may be reached if and only if

is 0. The former may be reached if and only if  , thus:

, thus: | (2.7) |

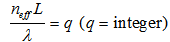

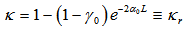

is integer. Furthermore, the resonance may be happens when the resonant coupling coefficient,

is integer. Furthermore, the resonance may be happens when the resonant coupling coefficient,  , fulfils a requirement as:

, fulfils a requirement as: | (2.8) |

of Eq. (2.5) becomes:

of Eq. (2.5) becomes: | (2.9) |

| (2.10) |

3. DFORR and Its Response Formula

- Seraji et al [29], specifically addressed it in 2012, and conducted its comparison with the CFORR for some

values. Based on Stokes formulation for the CFORR, we conduct analytical work for DFORR and present the amplitude fields of light interaction at port 1~4. It is described in relations mentioned bellow:

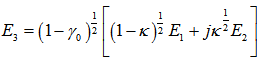

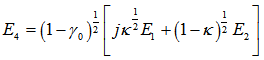

values. Based on Stokes formulation for the CFORR, we conduct analytical work for DFORR and present the amplitude fields of light interaction at port 1~4. It is described in relations mentioned bellow: 3.1. Intensities of Output and Loop of DFORR

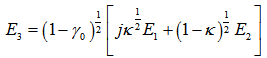

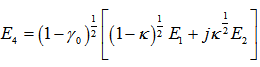

- With almost similar situation as mentioned in the previous section, we describe the complex amplitude of mode interaction as follows:

| (3.1) |

| (3.2) |

| (3.3) |

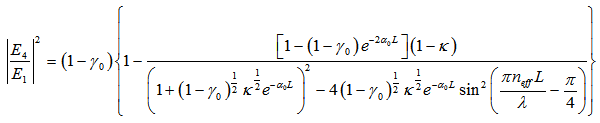

| (3.4) |

| (3.5) |

| (3.6) |

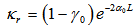

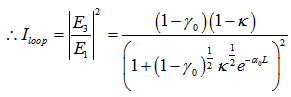

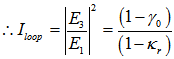

3.2. Resonance Condition for DFORR

- The resonance condition of the configuration may be achieved when

becomes maximum and at the same time,

becomes maximum and at the same time,  is 0. The former may be reached if and only if

is 0. The former may be reached if and only if  , thus at this condition we may gain:

, thus at this condition we may gain: | (3.7) |

| (3.8) |

is defined as the coupling coefficient at resonance condition. Furthermore, the normalized loop and output intensities may be derived respectively as:

is defined as the coupling coefficient at resonance condition. Furthermore, the normalized loop and output intensities may be derived respectively as: | (3.9) |

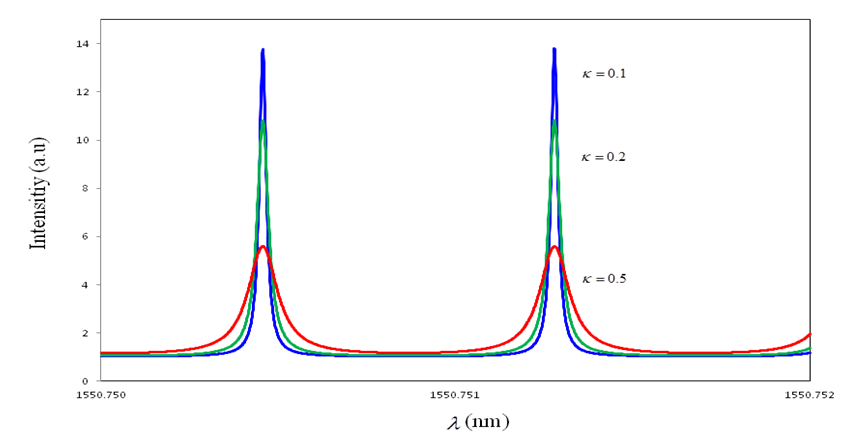

and

and  intensities are shown in Figure 4 and 5 respectively, with= 0.07 and

intensities are shown in Figure 4 and 5 respectively, with= 0.07 and  = 0.1, 0.2, 0.5.

= 0.1, 0.2, 0.5.  | Figure 4.  Graph for DFORR Graph for DFORR |

| Figure 5.  Graph for DFORR Graph for DFORR |

4.Comparison of Output and Loop Intensities for Both Configurations

- We present the comparison for both type configurations in this section. We vary the

value from 0.01 until 0.99 with interval of 0.01, then we compare the intensities,

value from 0.01 until 0.99 with interval of 0.01, then we compare the intensities,  and

and  for both configurations. With

for both configurations. With  varies 0.01 ~ 0.99,

varies 0.01 ~ 0.99,  and

and  reaches their first resonant points at

reaches their first resonant points at =1,550.75066 nm and 1,550.75046 nm for CFORR and DFORR respectively, i.e., the peak

=1,550.75066 nm and 1,550.75046 nm for CFORR and DFORR respectively, i.e., the peak  or dip

or dip  of DFORR slightly precedes than that of CFORR by

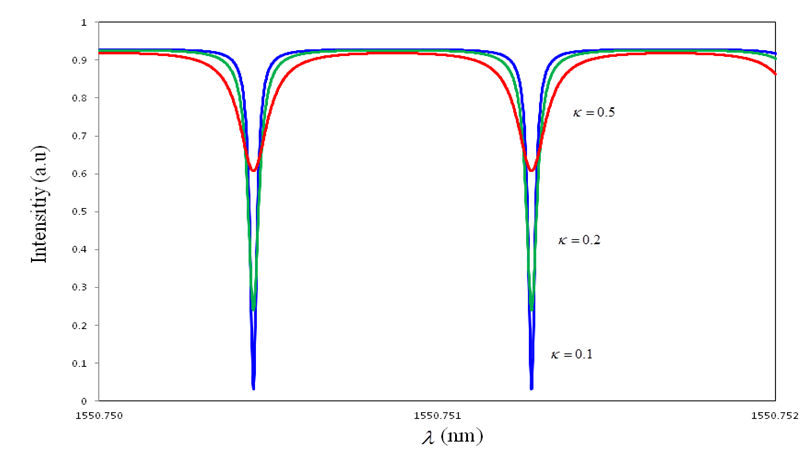

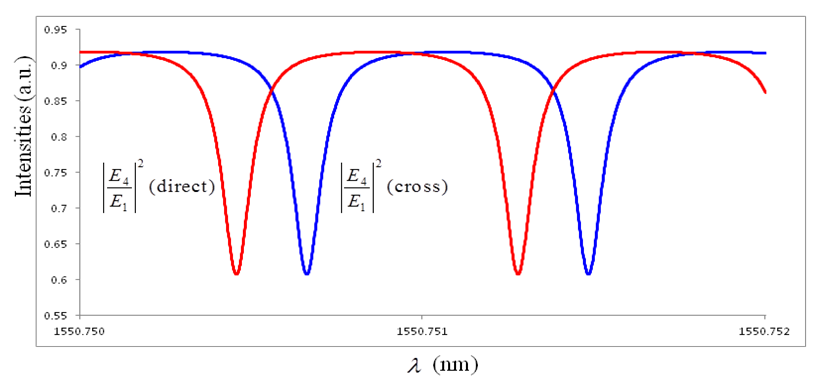

of DFORR slightly precedes than that of CFORR by  = 2.06x10-4 nm, and for more, they exhibit different behaviours. Figure 6 and 7 shows the comparison of

= 2.06x10-4 nm, and for more, they exhibit different behaviours. Figure 6 and 7 shows the comparison of  and

and  respectively, for

respectively, for  = 0.5. With

= 0.5. With  = 0.5, then the

= 0.5, then the  for DFORR has Free Spectral Range (FSR) = 8.22x10-4 nm which is exactly the same as that one of CFORR, and Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) = 1.27x10-4 nm which is 0.25x10-4 nm wider than that of CFORR. Meanwhile

for DFORR has Free Spectral Range (FSR) = 8.22x10-4 nm which is exactly the same as that one of CFORR, and Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) = 1.27x10-4 nm which is 0.25x10-4 nm wider than that of CFORR. Meanwhile  has FSR = 8.22x10-4 nm, which is the same value with that of CFORR but FWHM = 4.68x10-4 nm, which is slightly 0.01x10-4 nm narrower than that of the CFORR. This means that at

has FSR = 8.22x10-4 nm, which is the same value with that of CFORR but FWHM = 4.68x10-4 nm, which is slightly 0.01x10-4 nm narrower than that of the CFORR. This means that at  = 0.5, the Finesse of DFORR is slightly bigger by 4x10-3 more than that of CFORR.

= 0.5, the Finesse of DFORR is slightly bigger by 4x10-3 more than that of CFORR. | Figure 6. Graph for  CFORR and DFORR, when κ = 0.5 CFORR and DFORR, when κ = 0.5 |

| Figure 7. Graph for  CFORR and DFORR, when κ = 0.5 CFORR and DFORR, when κ = 0.5 |

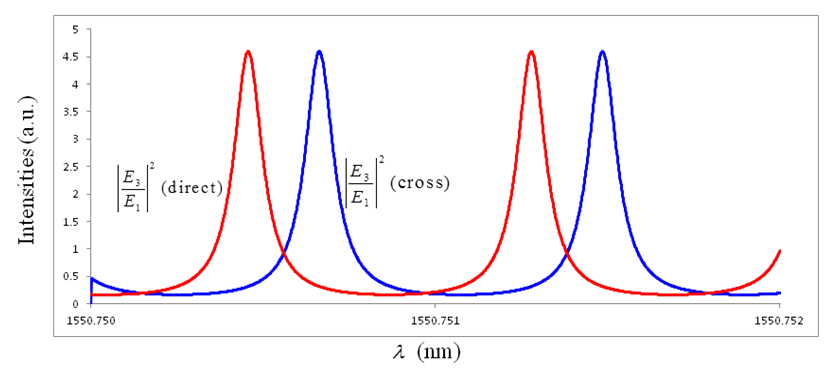

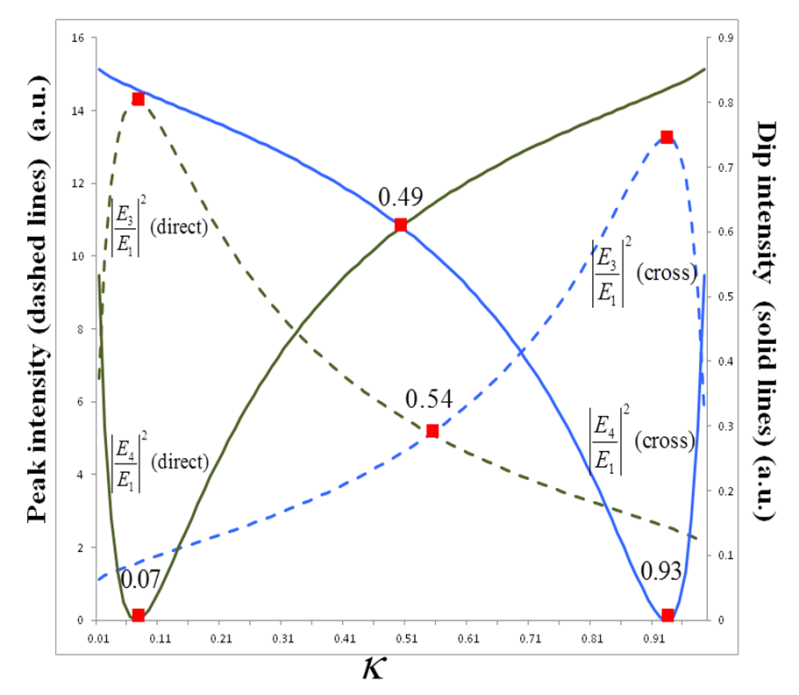

(peak, dashed line) and the minimum point for

(peak, dashed line) and the minimum point for  (dip, solid line) when CFORR (blue) and DFORR (brown) at resonance are shown at Figure 8, as the

(dip, solid line) when CFORR (blue) and DFORR (brown) at resonance are shown at Figure 8, as the  varies 0.01 ~ 0.99.

varies 0.01 ~ 0.99.  | Figure 8. Graph  (dashed line) and (dashed line) and  (solid line) at resonant conditions for CFORR (blue) and DFORR (brown) (solid line) at resonant conditions for CFORR (blue) and DFORR (brown) |

(dashed blue line), increases gradually with the increasing of

(dashed blue line), increases gradually with the increasing of  value, and after passing through at point of about

value, and after passing through at point of about  = 0.67, it rises more steeply until it reaches its maximum at point of

= 0.67, it rises more steeply until it reaches its maximum at point of  = 0.93, and then drops drastically for the rest high

= 0.93, and then drops drastically for the rest high  value. In contrast to this, dip intensity of CFORR

value. In contrast to this, dip intensity of CFORR  (solid blue line) decreases slowly with the increasing of

(solid blue line) decreases slowly with the increasing of  value, and after passing through at point of about

value, and after passing through at point of about  = 0.67, it decreases more sharply until it reaches its minimum at point of

= 0.67, it decreases more sharply until it reaches its minimum at point of  = 0.93, henceforth rises steeply for the rest of high

= 0.93, henceforth rises steeply for the rest of high  value. The significance of this graph is, when CFORR is utilized as sensor device by treating changes to its

value. The significance of this graph is, when CFORR is utilized as sensor device by treating changes to its  value through the application of external perturbation etc., then the best operating area is for

value through the application of external perturbation etc., then the best operating area is for  at around 0.67 ~ 0.99.Meanwhile, for DFORR, on contrary, the peak intensity,

at around 0.67 ~ 0.99.Meanwhile, for DFORR, on contrary, the peak intensity,  (dashed brown line), increases sharply with the increasing of

(dashed brown line), increases sharply with the increasing of  , and after reaching its maximum at point of

, and after reaching its maximum at point of  = 0.07, it falls relatively sharp until

= 0.07, it falls relatively sharp until  = 0.33, for thereafter decreases more gradually for the rest high

= 0.33, for thereafter decreases more gradually for the rest high  value. Furthermore, on the other hand, the dip intensity,

value. Furthermore, on the other hand, the dip intensity,  (solid brown line) decreases drastically with the increasing of

(solid brown line) decreases drastically with the increasing of  value, and after reaching its minimum at point of

value, and after reaching its minimum at point of  = 0.07, it increases more steeply until passing through point of

= 0.07, it increases more steeply until passing through point of  = 0.33, and henceforth rises more gradually for the rest of high

= 0.33, and henceforth rises more gradually for the rest of high  value.The significance of this graph is when it is utilized as sensor device by treating changes to its

value.The significance of this graph is when it is utilized as sensor device by treating changes to its  value, so the best operating boundaries for its

value, so the best operating boundaries for its  value is at around 0.01 ~ 0.33. Furthermore, the

value is at around 0.01 ~ 0.33. Furthermore, the  for both CFORR and DFORR have the same value when reaches around 0.55, meanwhile

for both CFORR and DFORR have the same value when reaches around 0.55, meanwhile  for both configurations have the same value when

for both configurations have the same value when  reaches 0.49. This concludes that when the value of

reaches 0.49. This concludes that when the value of  is around 0.5, analytically both configurations exhibit the same phenomena. In addition, during steady state condition, when there is no external perturbation that may be applied to change the

is around 0.5, analytically both configurations exhibit the same phenomena. In addition, during steady state condition, when there is no external perturbation that may be applied to change the  of the system, CFORR shows much better performance compared to DFORR, by the use of

of the system, CFORR shows much better performance compared to DFORR, by the use of  value at around 0.01 ~ 0.49. Meanwhile, DFORR shows much better performance with the use of

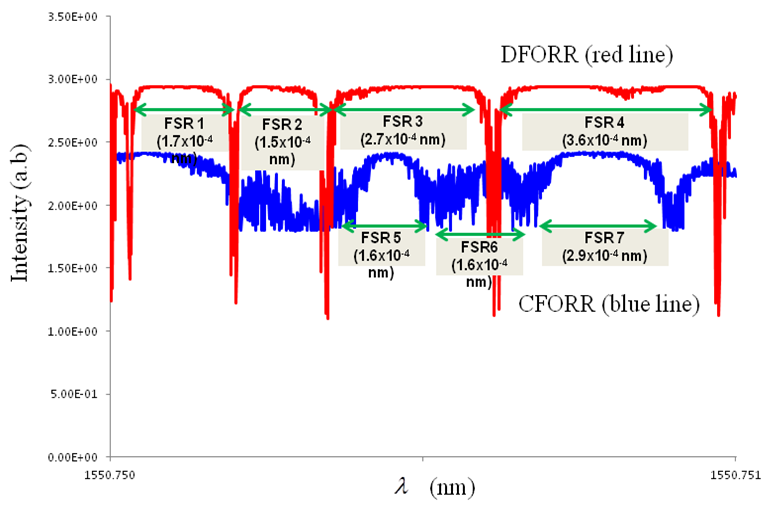

value at around 0.01 ~ 0.49. Meanwhile, DFORR shows much better performance with the use of  value around 0.49 ~ 0.99.We have conducted some experimental works as well, where Polarization Maintained Fiber, with 2x2 coupler of 50/50 is utilized to construct ring resonator of 2 m in length. We used Tunable Laser Source (TLS) as the light source and Optical Spectrum Analyzer (OSA) for the detection of the output intensity. The result for CFORR and DFORR is shown in Figure 9, where DFORR exhibits much better Finesse than that of CFORR. There are several dips appears with FSR around 1.7 ~ 3.6x10-4 nm. This inconsistency dips may occurs due to multiple misalignment wavelength interaction between light going direct to output port and light comes out after traveling inside the ring which is not always in the same phase to each other. Further discussion regarding to this experimental result will be published separately.

value around 0.49 ~ 0.99.We have conducted some experimental works as well, where Polarization Maintained Fiber, with 2x2 coupler of 50/50 is utilized to construct ring resonator of 2 m in length. We used Tunable Laser Source (TLS) as the light source and Optical Spectrum Analyzer (OSA) for the detection of the output intensity. The result for CFORR and DFORR is shown in Figure 9, where DFORR exhibits much better Finesse than that of CFORR. There are several dips appears with FSR around 1.7 ~ 3.6x10-4 nm. This inconsistency dips may occurs due to multiple misalignment wavelength interaction between light going direct to output port and light comes out after traveling inside the ring which is not always in the same phase to each other. Further discussion regarding to this experimental result will be published separately.  | Figure 9. Experimental Work Utilizing PMF with 50:50 Coupler |

5. Conclusions

- We have conducted a more detailed analytical work of

(normalized loop intensity) and

(normalized loop intensity) and  (normalized output intensity) performance, compared to previous work, where the coupling coefficient of utilized coupler,

(normalized output intensity) performance, compared to previous work, where the coupling coefficient of utilized coupler,  , is varied 0.01~0.99.The significance of this graph is, when CFORR is utilized as sensor device by treating changes to its

, is varied 0.01~0.99.The significance of this graph is, when CFORR is utilized as sensor device by treating changes to its  value through the application of external perturbation etc., then the best operating area is for

value through the application of external perturbation etc., then the best operating area is for  at around 0.67 ~ 0.99. On contrary, when DFORR is utilized as sensor device by treating changes to its

at around 0.67 ~ 0.99. On contrary, when DFORR is utilized as sensor device by treating changes to its  value, so the best operating boundaries for its

value, so the best operating boundaries for its  value is at around 0.01 ~ 0.33. During steady state condition, when there is no external perturbation that may be applied to change the

value is at around 0.01 ~ 0.33. During steady state condition, when there is no external perturbation that may be applied to change the  of the system, CFORR shows much better performance compared to DFORR, by the use of

of the system, CFORR shows much better performance compared to DFORR, by the use of  value at around 0.01~0.49. Meanwhile, DFORR shows much better performance with the use of

value at around 0.01~0.49. Meanwhile, DFORR shows much better performance with the use of  value around 0.49~0.99. Experimental work has been conducted to confirm the phenomena. We gain some FSR with the same orde with analytical work, but further discussion will be published in a separate paper. The results mentioned above also confirm that both configurations perform opposite situation to each other, and we may consider this situation for utilizing the best configuration for both. The analytical result gained in this work can be useful for the selection of configuration and purpose of FORR utilization.

value around 0.49~0.99. Experimental work has been conducted to confirm the phenomena. We gain some FSR with the same orde with analytical work, but further discussion will be published in a separate paper. The results mentioned above also confirm that both configurations perform opposite situation to each other, and we may consider this situation for utilizing the best configuration for both. The analytical result gained in this work can be useful for the selection of configuration and purpose of FORR utilization. Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML