-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Optics and Applications

p-ISSN: 2168-5053 e-ISSN: 2168-5061

2013; 3(4): 27-39

doi:10.5923/j.optics.20130304.01

Optics of solar concentrators Part I: Theoretical models of light collection

1Physics Department, University of Ferrara, Via Saragat 1, 44122 Ferrara (FE), Italy

2ENEA C.R. “E. Clementel”, Via Martiri di Monte Sole 4, 40129 Bologna (BO), Italy

Correspondence to: Antonio Parretta, Physics Department, University of Ferrara, Via Saragat 1, 44122 Ferrara (FE), Italy.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

A review of the theoretical models of light collection in solar concentrators, developed by the author in the last years, is here reported together with new advancements of the theoretical analysis which have led to the introduction of new optical concepts and to the definition of new optical quantities. For some of them a match was found with electrical quantities. Solar concentrators are regarded as generic optical elements whose reflectance, absorbance and transmittance properties are expressed with respect to different ways of irradiation. They are studied under collimated or diffuse light, under local or integral irradiation, including that in which light direction is reversed, that is directed from the exit towards the entrance aperture. All the results have been obtained applying two optical concepts: the reversibility principle and the efficiency of transmission through the solar concentrator of an elemental beam. This theoretical investigation of solar concentrators improves the knowledge of their optical properties, potentially expands the field of their applications and opens new perspectives to the methods of characterization.

Keywords: Solar Concentrator, Light Collection, Optical Characterization, Optical Modelling, Nonimaging Optics

Cite this paper: Antonio Parretta, Optics of solar concentrators Part I: Theoretical models of light collection, International Journal of Optics and Applications, Vol. 3 No. 4, 2013, pp. 27-39. doi: 10.5923/j.optics.20130304.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

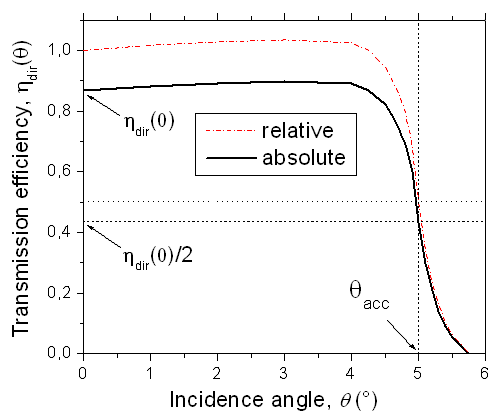

- Solar concentrators (SC) are usually investigated in order to know their optical transmission properties when they are irradiated by a uniform, collimated light beam simulating the direct component of the real solar radiation[1-6]. The most important result of this study is the curve of optical transmission efficiency drawn as function of the angle of incidence of the collimated beam respect to the optical axis of the concentrator (see Figure 1). The transmission curve is characterized by an acceptance angle,

, corresponding to the 50% of the efficiency measured at 0°. This is valid for generic applications, whereas, for photovoltaic applications, an acceptance angle,

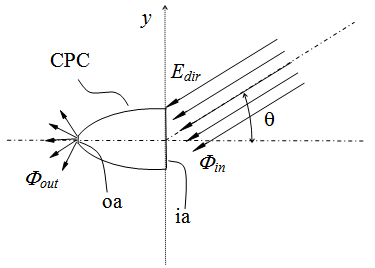

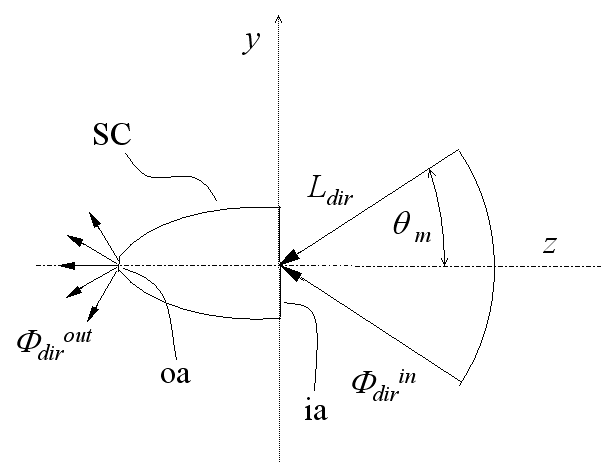

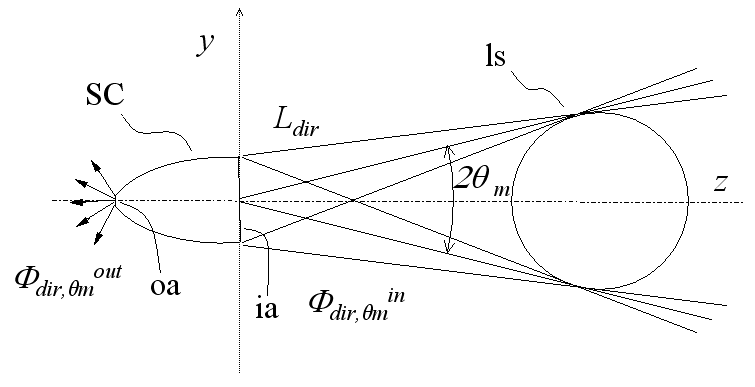

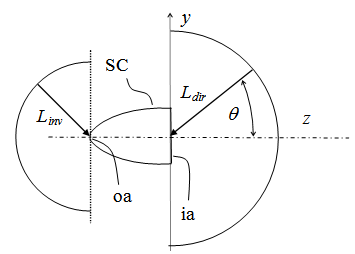

, corresponding to the 50% of the efficiency measured at 0°. This is valid for generic applications, whereas, for photovoltaic applications, an acceptance angle,  , corresponding to the 90% of the efficiency measured at 0°, is usually adopted[7-10]. The other important property which is largely investigated in a solar concentrator is the spatial or angular distribution of the flux on the receiver, of minor importance in thermal solar concentrators, but of crucial importance in photovoltaic solar concentrators[11,12].The optical transmission curve establishes how much precise must be the solar tracker, which brings the SC, when pointing towards the sun disk, in order to keep always the efficiency on the top of the curve[13], whereas the flux density distribution establishes if the system is suitable for the thermal or photovoltaic receiver, or if a secondary optical element (SOE) has to be added to it[14,15]. These are the basic information which are generally pursued, both theoretically or experimentally, by the people working on solar concentrators.In this paper we try to go beyond this view by proposing a new scenario in which a solar concentrator, regardless of the type, if 2-D or 3-D, if refractive or reflective, if imaging or nonimaging, is studied as a generic optical component for which reflection, absorption or transmission properties can be defined respect to specific models of irradiation. We can distinguish, for example, between “direct” and “inverse” irradiation depending on the direction of the incoming light, or between “local” and “integral” irradiation depending if the irradiation is limited to a point or a small area of the aperture, or if it is extended to the entire aperture area; we can finally distinguish between a quasi-collimated irradiation by a far light source, in contrast to a “diffuse” irradiation by a lambertian source. In the last case we speak of a “lambertian” irradiation, understood as an irradiation with constant radiance from all directions within a maximum value of solid angle. In what follows we talk about theoretical models of irradiation; these models are just simplifications of the real irradiation conditions which can be found outdoors. For each model we derive a specific method of characterization of the SC, that can be applied by optical simulations at a computer or by experimental measurements. The acronym assigned to each model of irradiation is the same of that assigned to the corresponding method of characterization. In what follows a generic solar concentrator is schematised as a device confined between an entrance aperture (ia) with area Ain and an exit aperture (oa) with area Aout, where Ain > Aout , as the definition of solar concentrator requires. A solar concentrator operates in practice under “direct” irradiation, that is under irradiation on the entrance aperture and with a receiver, the energy conversion device, at the exit aperture.

, corresponding to the 90% of the efficiency measured at 0°, is usually adopted[7-10]. The other important property which is largely investigated in a solar concentrator is the spatial or angular distribution of the flux on the receiver, of minor importance in thermal solar concentrators, but of crucial importance in photovoltaic solar concentrators[11,12].The optical transmission curve establishes how much precise must be the solar tracker, which brings the SC, when pointing towards the sun disk, in order to keep always the efficiency on the top of the curve[13], whereas the flux density distribution establishes if the system is suitable for the thermal or photovoltaic receiver, or if a secondary optical element (SOE) has to be added to it[14,15]. These are the basic information which are generally pursued, both theoretically or experimentally, by the people working on solar concentrators.In this paper we try to go beyond this view by proposing a new scenario in which a solar concentrator, regardless of the type, if 2-D or 3-D, if refractive or reflective, if imaging or nonimaging, is studied as a generic optical component for which reflection, absorption or transmission properties can be defined respect to specific models of irradiation. We can distinguish, for example, between “direct” and “inverse” irradiation depending on the direction of the incoming light, or between “local” and “integral” irradiation depending if the irradiation is limited to a point or a small area of the aperture, or if it is extended to the entire aperture area; we can finally distinguish between a quasi-collimated irradiation by a far light source, in contrast to a “diffuse” irradiation by a lambertian source. In the last case we speak of a “lambertian” irradiation, understood as an irradiation with constant radiance from all directions within a maximum value of solid angle. In what follows we talk about theoretical models of irradiation; these models are just simplifications of the real irradiation conditions which can be found outdoors. For each model we derive a specific method of characterization of the SC, that can be applied by optical simulations at a computer or by experimental measurements. The acronym assigned to each model of irradiation is the same of that assigned to the corresponding method of characterization. In what follows a generic solar concentrator is schematised as a device confined between an entrance aperture (ia) with area Ain and an exit aperture (oa) with area Aout, where Ain > Aout , as the definition of solar concentrator requires. A solar concentrator operates in practice under “direct” irradiation, that is under irradiation on the entrance aperture and with a receiver, the energy conversion device, at the exit aperture.  | Figure 1. Typical optical transmission curve of a nonimaging solar concentrator |

direction, is transmitted by the concentrator? This question introduces the first and simplest method of characterization of the solar concentrator: the “Direct Local Collimated Method” (DLCM)[16-18]. To apply this method in the most general form we should consider also the polarization of the beam and its spectrum. In what follows, however, we simplify our discussion by considering always unpolarized and monochromatic light at input. The role played by unpolarized light, in fact, has a significant importance in this work. On the one hand a solar concentrator works mainly with direct sunlight, which is strictly unpolarized, on the other one, in the following, all the presented methods of SC characterization require the use of unpolarized light.With the DLCM irradiation the elemental collimated beam is transmitted to output with an efficiency expressed by the quantity

direction, is transmitted by the concentrator? This question introduces the first and simplest method of characterization of the solar concentrator: the “Direct Local Collimated Method” (DLCM)[16-18]. To apply this method in the most general form we should consider also the polarization of the beam and its spectrum. In what follows, however, we simplify our discussion by considering always unpolarized and monochromatic light at input. The role played by unpolarized light, in fact, has a significant importance in this work. On the one hand a solar concentrator works mainly with direct sunlight, which is strictly unpolarized, on the other one, in the following, all the presented methods of SC characterization require the use of unpolarized light.With the DLCM irradiation the elemental collimated beam is transmitted to output with an efficiency expressed by the quantity  , the local optical transmission efficiency. When the test of the SC is performed on areas

, the local optical transmission efficiency. When the test of the SC is performed on areas  larger than the elementary area dAin around the point P of the input aperture (ia), we are able, for example, to check the equivalence of symmetric portions of the input area of a real SC. We talk in this way of efficiency of direct transmission from these areas as:

larger than the elementary area dAin around the point P of the input aperture (ia), we are able, for example, to check the equivalence of symmetric portions of the input area of a real SC. We talk in this way of efficiency of direct transmission from these areas as:  .If the irradiation of the SC by a collimated beam is extended to the entire area of input aperture, we talk about the “Direct Integral Collimated Method” (DICM) or simply the “Direct Collimated Method” (DCM) (hereafter we will remove the term “Integral”, considering it implicit, so we will add only the term “Local” when we are irradiating only a portion of the aperture)[18,19]. Figure 2 illustrates the DCM. Before describing it, as well as the other methods discussed in this work, it is necessary to go to an “ab initio” investigation of the SC under the irradiation of an elementary beam.

.If the irradiation of the SC by a collimated beam is extended to the entire area of input aperture, we talk about the “Direct Integral Collimated Method” (DICM) or simply the “Direct Collimated Method” (DCM) (hereafter we will remove the term “Integral”, considering it implicit, so we will add only the term “Local” when we are irradiating only a portion of the aperture)[18,19]. Figure 2 illustrates the DCM. Before describing it, as well as the other methods discussed in this work, it is necessary to go to an “ab initio” investigation of the SC under the irradiation of an elementary beam.  | Figure 2. Basic scheme of the Direct Collimated Method (DCM) |

the incidence angle and with

the incidence angle and with  the transmission angle (by reflection or refraction), it can be found, by Eqs. (1a) and (1b), that the transmission factors Trefl for reflection and Trefr for refraction do not change at exchanging

the transmission angle (by reflection or refraction), it can be found, by Eqs. (1a) and (1b), that the transmission factors Trefl for reflection and Trefr for refraction do not change at exchanging  and

and  angles, that is inverting the direction of travel of the light path, as established by the “reversibility principle”: “the attenuation undergone by an unpolarized beam on the same path, but at opposite direction, is the same”.

angles, that is inverting the direction of travel of the light path, as established by the “reversibility principle”: “the attenuation undergone by an unpolarized beam on the same path, but at opposite direction, is the same”.  | (1a) |

| (1b) |

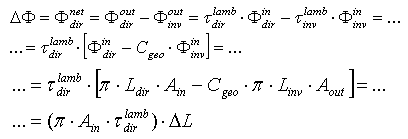

is the constant radiance of the inverse lambertian source.

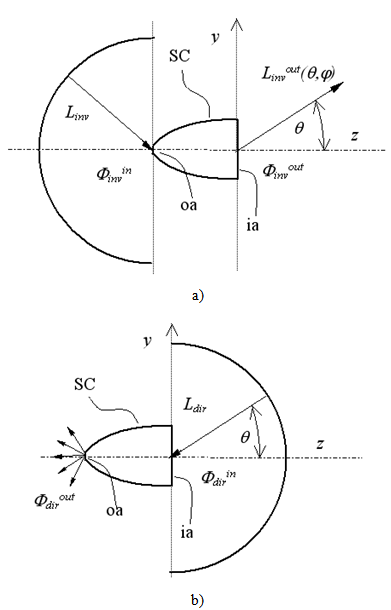

is the constant radiance of the inverse lambertian source.  | Figure 4. a) Scheme of the “Inverse Lambertian Method” (ILM). b) Scheme of the “Direct Lambertian Method” (DLM). In both cases we consider a limit polar angle  = 90° = 90° |

is the constant radiance of the direct lambertian source. If the concentrator is irradiated simultaneously in “direct” and “inverse” modes by lambertian sources, all the connecting paths will overlap and, putting

is the constant radiance of the direct lambertian source. If the concentrator is irradiated simultaneously in “direct” and “inverse” modes by lambertian sources, all the connecting paths will overlap and, putting  =

= , also the elementary flux flowing through any connecting path will be the same along the two directions. Then, with

, also the elementary flux flowing through any connecting path will be the same along the two directions. Then, with  =

= , also the total flux flowing through the concentrator from one aperture to the other will be the same in the two directions. The irradiation of the SC by diffused lambertian sources introduces in this way the “lambertian” methods of irradiation, based on the irradiation with constant radiance from any direction: the “Direct Lambertian Method” (DLM) shown in Figure 4b with light incident on the input aperture[16,17,19,25], and the “Inverse Lambertian Method” (ILM) shown in Figure 4a with light incident on the output aperture[21-25]. In the following Section, the models briefly outlined so far will be investigated in detail.

, also the total flux flowing through the concentrator from one aperture to the other will be the same in the two directions. The irradiation of the SC by diffused lambertian sources introduces in this way the “lambertian” methods of irradiation, based on the irradiation with constant radiance from any direction: the “Direct Lambertian Method” (DLM) shown in Figure 4b with light incident on the input aperture[16,17,19,25], and the “Inverse Lambertian Method” (ILM) shown in Figure 4a with light incident on the output aperture[21-25]. In the following Section, the models briefly outlined so far will be investigated in detail.2. Theoretical Models of Light Collection

2.1. Theory of the “Direct Collimated Methods”

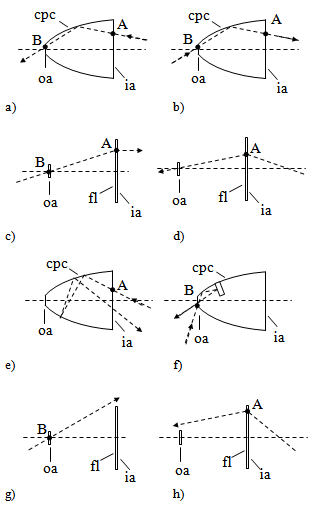

- An elementary beam, incident on the point A of (ia) and flowing inside the SC in the direct mode, (see Figures 3a, d), will be transmitted to the output with an efficiency

≤ 1. Alternatively, the elementary beam will be reflected backwards (Figure 3e) or totally absorbed inside SC (Figure 3h). In practice, the DLCM is easily applied by utilising a laser beam as it illustrated in[16-18]. If

≤ 1. Alternatively, the elementary beam will be reflected backwards (Figure 3e) or totally absorbed inside SC (Figure 3h). In practice, the DLCM is easily applied by utilising a laser beam as it illustrated in[16-18]. If  is averaged over a uniform distribution of points P on the input aperture, the transmission efficiency

is averaged over a uniform distribution of points P on the input aperture, the transmission efficiency  at collimated light of the SC can be approximately estimated[16]. The precise estimation of

at collimated light of the SC can be approximately estimated[16]. The precise estimation of  , however, requires the full irradiation of input aperture by a collimated and uniform light beam, and this is obtained by the application of the “Direct Collimated Method” (DCM), the most appropriate method to simulate the behaviour of a SC operating under the direct solar irradiation. As we have seen in the Introduction, the most important quantity summarizing the properties of light collection of a solar concentrator (SC) is its “absolute” transmission efficiency

, however, requires the full irradiation of input aperture by a collimated and uniform light beam, and this is obtained by the application of the “Direct Collimated Method” (DCM), the most appropriate method to simulate the behaviour of a SC operating under the direct solar irradiation. As we have seen in the Introduction, the most important quantity summarizing the properties of light collection of a solar concentrator (SC) is its “absolute” transmission efficiency  , expressed as function of the polar and azimuthal angles of direction of the collimated beam, characterized by a constant irradiance Edir on the wave front (see Figure 2):

, expressed as function of the polar and azimuthal angles of direction of the collimated beam, characterized by a constant irradiance Edir on the wave front (see Figure 2):  | (2a) |

is the area of input aperture projected along direction

is the area of input aperture projected along direction  . If the contour of input aperture is contained on a plane surface, Eq. (2a) simplifies as:

. If the contour of input aperture is contained on a plane surface, Eq. (2a) simplifies as:  | (2b) |

can be expressed as:

can be expressed as:  | (3) |

is the “relative” transmission efficiency of the SC and

is the “relative” transmission efficiency of the SC and  is the transmission efficiency at 0° (see Figure 1). It is clear that

is the transmission efficiency at 0° (see Figure 1). It is clear that  is the average value of

is the average value of  , the local, collimated optical efficiency, when

, the local, collimated optical efficiency, when  is calculated for all the points of the entrance aperture. We have therefore for the output flux:

is calculated for all the points of the entrance aperture. We have therefore for the output flux:  | (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

= 0, that is

= 0, that is  should be infinite to have a finite flux at input, and this is impossible to reach in practice. In an ideal experiment, we could imagine collimating light from a dimensionless source placed in the focus of a parabolic mirror, or to collect light from a source of finite dimension placed at infinite distance: in both cases the radiance of the light source becomes infinite. So we can write more precisely for the direct optical efficiency under a collimated beam:

should be infinite to have a finite flux at input, and this is impossible to reach in practice. In an ideal experiment, we could imagine collimating light from a dimensionless source placed in the focus of a parabolic mirror, or to collect light from a source of finite dimension placed at infinite distance: in both cases the radiance of the light source becomes infinite. So we can write more precisely for the direct optical efficiency under a collimated beam: | (7) |

is the radiance, from the

is the radiance, from the  direction, of a finite source at finite distance, and the symbol

direction, of a finite source at finite distance, and the symbol  is for “transmitted”. To explore the full properties of light collection of the SC, the collimated beam must be oriented respect to the optical (z) axis of concentrator varying

is for “transmitted”. To explore the full properties of light collection of the SC, the collimated beam must be oriented respect to the optical (z) axis of concentrator varying  in the 0°-90° interval and in the 0°-360° interval. If the SC has cylindrical (rotational) symmetry, it is sufficient to fix a

in the 0°-90° interval and in the 0°-360° interval. If the SC has cylindrical (rotational) symmetry, it is sufficient to fix a  value and to vary only

value and to vary only  . Generally, the SCs have squared or hexagonal input apertures, because these geometries allow to pack better them in a concentrating module, then the

. Generally, the SCs have squared or hexagonal input apertures, because these geometries allow to pack better them in a concentrating module, then the  angle can be limited, in these cases, to the 0°-90° or the 0°-60° interval, respectively. Despite this limitation, however, the number of measurements required by the application of DCM is very high, both for simulations and for experimental measurements. This is indeed the very strong limit of DCM applied to the determination of

angle can be limited, in these cases, to the 0°-90° or the 0°-60° interval, respectively. Despite this limitation, however, the number of measurements required by the application of DCM is very high, both for simulations and for experimental measurements. This is indeed the very strong limit of DCM applied to the determination of  . This limit can be overcome by the use of the “Inverse Lambertian Method” (ILM) of irradiation, as it is demonstrated in Section 2.3. Dealing with “nonimaging” SCs[1,2,26], whose transmission curve has a step-like profile (see Figure 1), their characterization by DCM can be simplified; it is sufficient in fact to vary the input

. This limit can be overcome by the use of the “Inverse Lambertian Method” (ILM) of irradiation, as it is demonstrated in Section 2.3. Dealing with “nonimaging” SCs[1,2,26], whose transmission curve has a step-like profile (see Figure 1), their characterization by DCM can be simplified; it is sufficient in fact to vary the input  angle from 0° to a little more than the acceptance angle at 50% of 0° efficiency,

angle from 0° to a little more than the acceptance angle at 50% of 0° efficiency,  . The rays incident at

. The rays incident at  , in fact, will be rejected back by the SC before reaching the output aperture. The quantity

, in fact, will be rejected back by the SC before reaching the output aperture. The quantity  (see Figure 1) represents the fraction of flux transferred to the output, and then it represents the “direct transmittance” at collimated light, or “direct collimated transmittance” of the SC, when it is viewed as a generic optical component. In like manner, we can speak of a “direct collimated reflectance”

(see Figure 1) represents the fraction of flux transferred to the output, and then it represents the “direct transmittance” at collimated light, or “direct collimated transmittance” of the SC, when it is viewed as a generic optical component. In like manner, we can speak of a “direct collimated reflectance”  or of a “direct collimated absorptance”

or of a “direct collimated absorptance”  of the SC for the fraction back reflected or absorbed of the input flux, respectively:

of the SC for the fraction back reflected or absorbed of the input flux, respectively:  | (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

is however possible in principle; it is a simple task by simulation (see the forthcoming parts of this work); more difficult it is to do it with experimental measurements.A typical curve of

is however possible in principle; it is a simple task by simulation (see the forthcoming parts of this work); more difficult it is to do it with experimental measurements.A typical curve of  for a 3-D nonimaging concentrator like a CPC (Compound Parabolic Concentrator) is illustrated in Figure 1[1,2,26]. Here the

for a 3-D nonimaging concentrator like a CPC (Compound Parabolic Concentrator) is illustrated in Figure 1[1,2,26]. Here the  angle is not represented as the CPC has a cylindrical symmetry. We distinguish the 0° efficiency

angle is not represented as the CPC has a cylindrical symmetry. We distinguish the 0° efficiency  , the acceptance angle at 50% of 0° efficiency

, the acceptance angle at 50% of 0° efficiency  and the relative transmission curve

and the relative transmission curve  , characterized by the same

, characterized by the same  angle, as it can be easily demonstrated. Respect to solar concentrators like the nonimaging CPCs, the “imaging” solar concentrators show a very different transmission curve, with a long tail and a short flat portion at small angles[1]. For these concentrators the DCM has to be applied by varying the polar angles from 0° to a limit

angle, as it can be easily demonstrated. Respect to solar concentrators like the nonimaging CPCs, the “imaging” solar concentrators show a very different transmission curve, with a long tail and a short flat portion at small angles[1]. For these concentrators the DCM has to be applied by varying the polar angles from 0° to a limit  angle,

angle,  , well higher than

, well higher than  . The transmission curves

. The transmission curves  or

or  are defined for a perfectly collimated light and can be drawn easily by simulations with an optical code. With experimental measurements, however, the beam will be quasi-collimated, with a divergence angle which depends on the design of the apparatus, so the drawing of the

are defined for a perfectly collimated light and can be drawn easily by simulations with an optical code. With experimental measurements, however, the beam will be quasi-collimated, with a divergence angle which depends on the design of the apparatus, so the drawing of the  curve in this case contains a margin of indetermination.

curve in this case contains a margin of indetermination. 2.2. Theory of the “Direct Lambertian Methods”

- The “Direct Lambertian Method” (DLM)[16,17,19,25] allows to study the transmission efficiency of a concentrator when the irradiation at input is integrated over all the directions in space. DLM simulates the behaviour of the concentrator under diffused light, for example the diffuse solar radiation in a totally covered sky. A clear sky, in fact, contrary to appearances, is not a good example of isotropic light, because the polarization of solar light by Rayleigh scattering produces a radiance strongly dependent on the direction of diffuse light respect to the direction of Sun[27]. Figure 4b shows the scheme of DLM applied to a 3D-CPC concentrator, with

constant radiance of the diffused light source. The total incident flux is:

constant radiance of the diffused light source. The total incident flux is: | (11) |

is the étendue. In the following, we will consider, for simplicity, only concentrators with cylindrical symmetry, then

is the étendue. In the following, we will consider, for simplicity, only concentrators with cylindrical symmetry, then  will be set equal to

will be set equal to  . The equations can be easily extended, whenever necessary, to the general case by reintroducing the dependence on the azimuthal angle

. The equations can be easily extended, whenever necessary, to the general case by reintroducing the dependence on the azimuthal angle  . The flux “transmitted” to the output aperture becomes:

. The flux “transmitted” to the output aperture becomes:  | (12) |

and to the “absorbed” flux

and to the “absorbed” flux  are expressed respectively as:

are expressed respectively as: | (13) |

| (14) |

. Here

. Here  is the “direct collimated reflectance” and

is the “direct collimated reflectance” and  is the “direct collimated absorptance” of the concentrator, as previously defined. DLM gives the “direct lambertian transmission efficiency”

is the “direct collimated absorptance” of the concentrator, as previously defined. DLM gives the “direct lambertian transmission efficiency”  , also called “direct lambertian transmittance”

, also called “direct lambertian transmittance”  , defined as the ratio of output to input flux:

, defined as the ratio of output to input flux:  | (15) |

and the “direct lambertian absorptance”

and the “direct lambertian absorptance”  :

:  | (16) |

| (17) |

=1.The output radiance, in general, is not constant like the input radiance, so we speak about an average output radiance:

=1.The output radiance, in general, is not constant like the input radiance, so we speak about an average output radiance:  | (18) |

is the geometrical concentration ratio. Now we define a new quantity,

is the geometrical concentration ratio. Now we define a new quantity,  , the ratio between output and input radiance:

, the ratio between output and input radiance:  | (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

as the “optical concentration ratio under direct lambertian irradiation” or “direct lambertian concentration ratio”. The direct lambertian model can be applied also reducing the angular extension of the lambertian source from π/2 to a limit polar angle

as the “optical concentration ratio under direct lambertian irradiation” or “direct lambertian concentration ratio”. The direct lambertian model can be applied also reducing the angular extension of the lambertian source from π/2 to a limit polar angle  (see Figure 5). The corresponding method, DLM

(see Figure 5). The corresponding method, DLM , is particularly useful when we analyse the behaviour of nonimaging SCs. Because of the step-like profile of their optical efficiency (

, is particularly useful when we analyse the behaviour of nonimaging SCs. Because of the step-like profile of their optical efficiency ( ≈ 0 for

≈ 0 for  ), in fact, the characterization of these SCs under direct lambertian irradiation can be limited to angles

), in fact, the characterization of these SCs under direct lambertian irradiation can be limited to angles  , reducing in this way the time of computer elaboration or simplifying the experimental measurements.

, reducing in this way the time of computer elaboration or simplifying the experimental measurements.  | Figure 5. Scheme of the “Direct Lambertian Method  ”, DLM ( ”, DLM ( ) ) |

can simulate the irradiation of a SC by a near lambertian light source, as illustrated in Figure 6. The theory of DLM

can simulate the irradiation of a SC by a near lambertian light source, as illustrated in Figure 6. The theory of DLM is just that developed until now for the DLM, modified in the limit polar angle of the diffused irradiation. We have therefore for the input and output flux:

is just that developed until now for the DLM, modified in the limit polar angle of the diffused irradiation. We have therefore for the input and output flux:  | (22) |

| (23) |

| Figure 6. Irradiation of the SC by a nearby lambertian source (ls) |

| (24) |

| (25) |

is:

is:  | (26) |

2.3. Theory of the “Inverse Lambertian Methods”

- We saw in the Introduction that, for the reversibility principle, the optical loss reported by a direct ray is the same as that shown by an inverse ray if the optical path is the same and if both starting rays are unpolarized. The attenuation factor for the radiance of the direct beam incident at point A in direction

represents the local direct transmission efficiency

represents the local direct transmission efficiency  (see Figure 3a), while the attenuation factor for the radiance of the ray emitted by the SC from point A in the reverse direction

(see Figure 3a), while the attenuation factor for the radiance of the ray emitted by the SC from point A in the reverse direction  (see Figure 3b) represents the local inverse transmission efficiency

(see Figure 3b) represents the local inverse transmission efficiency  . We extend now these concepts to all points of

. We extend now these concepts to all points of  directly irradiated in direction

directly irradiated in direction  (DCM, see Figure 2) and to the same points of

(DCM, see Figure 2) and to the same points of  that emit light in the reverse direction

that emit light in the reverse direction  (ILM, see Figure 4a). If the inverse radiance at output aperture

(ILM, see Figure 4a). If the inverse radiance at output aperture  (Figure 4a) is constant for all directions, that is, if the source at output aperture is Lambertian, then the inverse output radiance,

(Figure 4a) is constant for all directions, that is, if the source at output aperture is Lambertian, then the inverse output radiance,  , averaged over all points of

, averaged over all points of  , must have the same angular distribution of the inverse transmission efficiency

, must have the same angular distribution of the inverse transmission efficiency  , averaged over all points of

, averaged over all points of  . But the average inverse transmission efficiency

. But the average inverse transmission efficiency  must have the same angular distribution of the average direct transmission efficiency

must have the same angular distribution of the average direct transmission efficiency  , because the transmission of the single connecting paths is invariant respect to the direction of travel of light. As a consequence, we can affirm that the inverse radiance of the concentrator

, because the transmission of the single connecting paths is invariant respect to the direction of travel of light. As a consequence, we can affirm that the inverse radiance of the concentrator  , irradiated on the output aperture with a uniform and non-polarized Lambertian source, is proportional to the efficiency of the direct transmission

, irradiated on the output aperture with a uniform and non-polarized Lambertian source, is proportional to the efficiency of the direct transmission  of a non-polarized collimated beam, that is the two corresponding relative quantities coincide. We have therefore that:

of a non-polarized collimated beam, that is the two corresponding relative quantities coincide. We have therefore that: | (27) |

| (28) |

| (29) |

(see Figure 1). The simulated and experimental measurements of relative inverse radiance

(see Figure 1). The simulated and experimental measurements of relative inverse radiance  of a solar concentrator is discussed elsewhere[21-25]. Here we recall that, to perform these measurements, it is sufficient to project the inverse light of concentrator towards a far planar screen and to record the image produced there; a simple elaboration of the image gives

of a solar concentrator is discussed elsewhere[21-25]. Here we recall that, to perform these measurements, it is sufficient to project the inverse light of concentrator towards a far planar screen and to record the image produced there; a simple elaboration of the image gives  , and so

, and so  . Here we want to emphasize another fundamental aspect of ILM, that is the fact that it provides also the value of

. Here we want to emphasize another fundamental aspect of ILM, that is the fact that it provides also the value of  , and so the “absolute” transmission efficiency (see Eqs. (3), (29)), without recourse to any direct measure by DCM[24,25], as it will be demonstrated by the following considerations.When the SC is irradiated in the reverse way (see Figure 4a), the exit aperture (oa) of area

, and so the “absolute” transmission efficiency (see Eqs. (3), (29)), without recourse to any direct measure by DCM[24,25], as it will be demonstrated by the following considerations.When the SC is irradiated in the reverse way (see Figure 4a), the exit aperture (oa) of area  becomes a Lambertian source with constant and uniform radiance

becomes a Lambertian source with constant and uniform radiance  . The total flux, injected into the SC and function of radiance

. The total flux, injected into the SC and function of radiance  , becomes:

, becomes:  | (30) |

of the SC, is given by:

of the SC, is given by:  | (31) |

is the radiance of light inversely emitted towards

is the radiance of light inversely emitted towards  . We now define the inverse lambertian transmission efficiency, or “inverse lambertian transmittance”,

. We now define the inverse lambertian transmission efficiency, or “inverse lambertian transmittance”,  , as the ratio of output to input flux:

, as the ratio of output to input flux: | (32) |

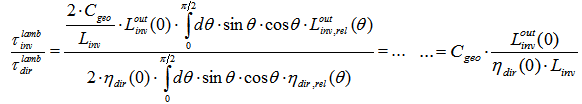

of Eq. (32) with the direct lambertian transmittance

of Eq. (32) with the direct lambertian transmittance  of Eq. (15) by taking their ratio:

of Eq. (15) by taking their ratio:  | (33) |

by applying the simple condition

by applying the simple condition  =

=  , at which the total integral flux transmitted in the “direct” and the “inverse” directions is the same:

, at which the total integral flux transmitted in the “direct” and the “inverse” directions is the same:  =

=  , because such is the flux transmitted through the elementary connecting paths in the two directions. By putting

, because such is the flux transmitted through the elementary connecting paths in the two directions. By putting  =

=  and using Eqs. (12) and (31) we find:

and using Eqs. (12) and (31) we find: | (34a) |

=

=  and applying Eqs. (28), (29), we have:

and applying Eqs. (28), (29), we have: | (34b) |

| (34c) |

by ILM measuring

by ILM measuring  , the average on-axis inverse radiance of SC, and

, the average on-axis inverse radiance of SC, and  , the radiance of the inverse lambertian source[24,25]. From Eq.s (33), (34c) we find moreover that the ratio between the inverse and direct lambertian transmittances is equal to

, the radiance of the inverse lambertian source[24,25]. From Eq.s (33), (34c) we find moreover that the ratio between the inverse and direct lambertian transmittances is equal to  , that is independent on radiance, as foreseen. This could be also deduced by considering that, if

, that is independent on radiance, as foreseen. This could be also deduced by considering that, if  = , we have:

= , we have:  | (35) |

times its “direct lambertian transmittance”, or equivalently: the “input direct lambertian flux” needed to sustain an equal transmitted flux in the opposite directions is

times its “direct lambertian transmittance”, or equivalently: the “input direct lambertian flux” needed to sustain an equal transmitted flux in the opposite directions is  times the “input inverse lambertian flux”. This result is not surprising; it is a direct consequence of the geometrical asymmetry of the concentrator and disappears when

times the “input inverse lambertian flux”. This result is not surprising; it is a direct consequence of the geometrical asymmetry of the concentrator and disappears when  =1, that is

=1, that is =

= . It is interesting to note that this result does not require any information about the internal features of the SC, but is only dependent on the sizes of the lateral apertures. Eq. (35) tell us that the optical “transparency” of the SC to lambertian light is not symmetric. Let us imagine now to irradiate both apertures of the SC by two different lambertian sources with

. It is interesting to note that this result does not require any information about the internal features of the SC, but is only dependent on the sizes of the lateral apertures. Eq. (35) tell us that the optical “transparency” of the SC to lambertian light is not symmetric. Let us imagine now to irradiate both apertures of the SC by two different lambertian sources with  ≠

≠ (see Figure 7). If

(see Figure 7). If  is the difference of incidence radiance between input and output, then we have for the net flux through SC, in the direct direction:

is the difference of incidence radiance between input and output, then we have for the net flux through SC, in the direct direction: | (36) |

| Figure 7. Scheme of the irradiation of the SC by both “Direct Lambertian Method” (DLM) with radiance Ldir and “Inverse Lambertian Method” (ILM) with radiance Linv |

= 0). Eq. (36) has a strong similarity with the Ohm’s law:

= 0). Eq. (36) has a strong similarity with the Ohm’s law: , where

, where  (W) has the role of current, (W/sr·m2) the role of potential difference and

(W) has the role of current, (W/sr·m2) the role of potential difference and  (sr·m2) the role of conductance. The net flux inside the SC, indeed, is the natural optical partner of the electric current and the choice of the radiance as the optical partner of the electric potential is the only one which allows to put Eq. (36) in the form of the Ohm’s law. Attempts to assign the role of potential to the total input flux

(sr·m2) the role of conductance. The net flux inside the SC, indeed, is the natural optical partner of the electric current and the choice of the radiance as the optical partner of the electric potential is the only one which allows to put Eq. (36) in the form of the Ohm’s law. Attempts to assign the role of potential to the total input flux  or to the étendue

or to the étendue  are in fact unsuccessful. From Eq. (36) we define the “direct conductance under lambertian irradiation” or “direct lambertian optical conductance”

are in fact unsuccessful. From Eq. (36) we define the “direct conductance under lambertian irradiation” or “direct lambertian optical conductance”  :

: | (37) |

| (38) |

. From Eq. (38) we define the “inverse conductance under lambertian irradiation” or “inverse lambertian optical conductance”

. From Eq. (38) we define the “inverse conductance under lambertian irradiation” or “inverse lambertian optical conductance”  :

: | (39) |

| (40) |

| (41) |

times the “inverse” étendue and that the “inverse” transmittance is

times the “inverse” étendue and that the “inverse” transmittance is  times the “direct” transmittance.From Eq. (36) we derive the density of the net flux through the input aperture

times the “direct” transmittance.From Eq. (36) we derive the density of the net flux through the input aperture  (the average net flux flowing through the unit area of the input aperture inside the SC in direct way):

(the average net flux flowing through the unit area of the input aperture inside the SC in direct way):  | (42) |

.and the density of the net flux through the output aperture

.and the density of the net flux through the output aperture  (the average net flux flowing through the unit area of the output aperture inside the SC in the reverse way):

(the average net flux flowing through the unit area of the output aperture inside the SC in the reverse way):  | (43) |

.If

.If  is the length of the SC, we can introduce the quantity

is the length of the SC, we can introduce the quantity  , the average gradient of radiance through the concentrator, a quantity which cannot be measured in practice, but which can be imagined to exist inside the concentrator from a theoretical point of view. Eq. (42) becomes:

, the average gradient of radiance through the concentrator, a quantity which cannot be measured in practice, but which can be imagined to exist inside the concentrator from a theoretical point of view. Eq. (42) becomes:  | (44) |

is intended as the average of the gradient of

is intended as the average of the gradient of  . Eq. (44) is optically equivalent to the Ohm’s law expressed in local form:

. Eq. (44) is optically equivalent to the Ohm’s law expressed in local form:  , with

, with  (W/m2) with the role of current density, gradΔL (W/sr·m3) with the role of electric field and

(W/m2) with the role of current density, gradΔL (W/sr·m3) with the role of electric field and  (sr·m) with the role of electrical conductivity. The equivalent expression for the inverse current density is given by:

(sr·m) with the role of electrical conductivity. The equivalent expression for the inverse current density is given by:  | (45) |

and an “inverse lambertian optical conductivity”

and an “inverse lambertian optical conductivity”  of a solar concentrator as follows:

of a solar concentrator as follows: | (46) |

| (47) |

| (48) |

times its “direct optical conductivity”, so it restores the asymmetry of the concentrator, as we have found for the transmittance efficiency.As we have seen for the direct local collimated method (DLCM), which applies only to a portion of input opening, the local inverse method can be applied fruitfully to small or large areas of the exit opening. We talk in this way of areas

times its “direct optical conductivity”, so it restores the asymmetry of the concentrator, as we have found for the transmittance efficiency.As we have seen for the direct local collimated method (DLCM), which applies only to a portion of input opening, the local inverse method can be applied fruitfully to small or large areas of the exit opening. We talk in this way of areas  , and of efficiency of direct transmission to these areas as:

, and of efficiency of direct transmission to these areas as:  . The

. The  efficiency can be obtained by applying the ILLM method to measurements of

efficiency can be obtained by applying the ILLM method to measurements of  , when the receiver is inversely irradiated by a lambertian source placed in the

, when the receiver is inversely irradiated by a lambertian source placed in the  area and centred on point P. The new situation is similar to that which would occur if the concentrator could be amended as follows: the new receiver is the selected area of the old receiver; the new concentrator is the old concentrator plus the excluded area of the receiver. This new way of looking at the receiver is very powerful. In this way, in fact, we can study the efficiency of collection of any portion of the optical receiver, and since the radiation on the receiver is generally not uniform when the concentrator is directly irradiated, it happens often to be wonder about the direction of the direct rays arriving in a certain area of the receiver. By applying the ILLM method, therefore, we can know from which direction the rays in excess in a certain area of the receiver arrive, or from which direction they are failing to arrive in a certain area of it. In a forthcoming part of this work, the applications of the ILLM method to nonimaging CPCs will be shown. Recent developments of the “inverse lambertian method” have been proposed by Herrero et al.[30,31], which have shown that the method can be modified in a way suitable to use the solar cell as receiver in PV concentrators, and have proposed the use of a parabolic mirror to project the inverse light of concentrator towards the planar screen. In a subsequent work, Parretta et al.[32] have modified the Herrero method by extending the use of the parabolic mirror also for measurements on a generic SC (photovoltaic or thermodynamic).

area and centred on point P. The new situation is similar to that which would occur if the concentrator could be amended as follows: the new receiver is the selected area of the old receiver; the new concentrator is the old concentrator plus the excluded area of the receiver. This new way of looking at the receiver is very powerful. In this way, in fact, we can study the efficiency of collection of any portion of the optical receiver, and since the radiation on the receiver is generally not uniform when the concentrator is directly irradiated, it happens often to be wonder about the direction of the direct rays arriving in a certain area of the receiver. By applying the ILLM method, therefore, we can know from which direction the rays in excess in a certain area of the receiver arrive, or from which direction they are failing to arrive in a certain area of it. In a forthcoming part of this work, the applications of the ILLM method to nonimaging CPCs will be shown. Recent developments of the “inverse lambertian method” have been proposed by Herrero et al.[30,31], which have shown that the method can be modified in a way suitable to use the solar cell as receiver in PV concentrators, and have proposed the use of a parabolic mirror to project the inverse light of concentrator towards the planar screen. In a subsequent work, Parretta et al.[32] have modified the Herrero method by extending the use of the parabolic mirror also for measurements on a generic SC (photovoltaic or thermodynamic).3. Conclusions

- In conclusion, we have presented in this work a general theoretical approach to the study of a solar concentrator looked at as a generic optical component. Irrespective of its practical way of use, we have considered any type of irradiation on the concentrator, and, for each type of irradiation, its reflection, absorption and transmission properties have been defined, both locally on its apertures and on its entire surface of its apertures. But, most importantly, the classical view of the concentrator fully irradiated on the front side by a collimated beam has been upset and a new way of looking to it has been introduced through the new concept of “inverse” irradiation. By inverting the irradiation of the concentrator and by using a lambertian distribution of light at the output, new and surprising results appear, which allow us, besides other things, to disclose the full direct optical transmission properties of the solar concentrator by a very simple approach. Besides this, we have been able to introduce new optical concepts and to define new optical quantities making similarities with electrical concepts. All the results have been obtained applying two optical concepts: the reversibility principle and the efficiency of transmission through the solar concentrator of an elemental beam. In the forthcoming parts of this work the simulations and the experimental measurements pertaining to the presented methods will be discussed in detail, referring in particular to nonimaging solar concentrators (CPCs).

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML