-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

Research in Ophthalmology

p-ISSN: 2471-7444 e-ISSN: 2471-7460

2018; 4(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.ophthal.20180401.01

Diabetes is a Barrier for Low Uptake of Cataract Surgical Services in India: A Population-Based Perspective

Sannapaneni Krishnaiah, Imtiaz Ahmed Sayed, Bharath Balasubramaniam, Ramanathan V. Ramani

Department of Community Outreach Services, Sankara Eye Foundation, Coimbatore, India

Correspondence to: Sannapaneni Krishnaiah, Department of Community Outreach Services, Sankara Eye Foundation, Coimbatore, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Aims: To assess the utilization of cataract surgery (CS) and barriers for low uptake of CS among people aged 50 years or older in India. Methods: It is a population-based, cross-sectional, epidemiologic survey conducted India. Presenting visual acuity (VA), history of cataract surgery and operable cataract were assessed house to house by trained field investigators. Information on barriers to CS were also collected. Results: The mean age was 63.8±8.9 (range 50-108 years) with equal gender distribution. In LR model, presence of diabetes and north Indian state of residence were significantly associated with lower CS (p<0.05). The odds of prevalence of CS was significantly lower in persons with diabetes; OR: 0.61; (95% CI: 0.38-0.94; p=0.028). Conclusion: The increasing prevalence of diabetes and lack of awareness about cataract are major challenges in cataract surgical uptake in India. This has public health implications in India especially due to epidemic increased proportion of diabetes.

Keywords: Cataract surgery, Barriers, Population based study, India

Cite this paper: Sannapaneni Krishnaiah, Imtiaz Ahmed Sayed, Bharath Balasubramaniam, Ramanathan V. Ramani, Diabetes is a Barrier for Low Uptake of Cataract Surgical Services in India: A Population-Based Perspective, Research in Ophthalmology, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2018, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.ophthal.20180401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are 285 million people visually impaired worldwide. Of these, 246 million have low vision (moderate or severe visual impairment) and 39 million are blind. About 90% of world’s visually impaired live in low-income settings. [1] In its new revised action plan, global agencies including WHO and its “Vision 2020 – The Right to Sight” are committed to elimination of avoidable blindness especially due to cataract by increasing the number and quality of cataract surgeries to achieve satisfactory visual outcome and improved quality of life by the year 2020. In doing so, the program aimed to achieve a reduction of 25% of visual impairment and blindness from the baseline estimate of the year 2010. [2]Population growth, ageing, urbanization, sedentary lifestyles and an increasing prevalence of obesity are increasing the number of people with diabetes and cataracts are the one of the most common causes of visual impairment in these population. [3] Previous studies conducted in India and other parts of the world have clearly demonstrated that diabetic patients with poor glycemic control need to be postponed their cataract surgery due to the unfit for the surgery as a result of presence of diabetes and risk of postoperative complications including delaying wound healing and increased infections and therefore presence of diabetes being one of the principle barriers for lesser cataract surgical uptake. [4, 7] There has been considerable research work done earlier on the barriers to use of existing cataract surgical services in India and worldwide. [8-13, 17-19, 21-24] However, there is little research literature available on diabetes and its association with cataract surgery uptake from India. The present study aimed at fulfilling this research gap and put forward few recommendations to address the priorities.

2. Methods and Materials

- A population based cross-sectional epidemiologic study was conducted in six Indian states of Tamil Nadu (TN), Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh (AP) in southern, Punjab in the north western, Gujarat in the western and Uttar Pradesh (UP) in Northern part of India from October 2015 to March 2016 using a multistage cluster random sampling strategy.

3. Sample

- The persons aged ≥50 years old residing in the selected study clusters for more than 6 months and consenting for interview and examination were considered eligible for the study. As part of the sampling procedures, list of districts were obtained from the states in which the base hospital operates its services. From this list, the first stage units of 20 districts were selected randomly; the first 10 districts were selected within a radius of 200 Kilometers that are being covered by a base hospital and the remaining 10 districts were selected randomly from the region where base hospital coverage (i.e., within 200 kilometers) is absent. This balance was maintained to ensure that the study participants were equally representatively recruited from serviced and not serviced districts by the base hospital. These districts ranged from a minimum of one in AP to a maximum of six in Karnataka. From selected districts, all villages/clusters were enumerated and listed out. Each village was considered as a cluster. On an average 3 to 4 clusters per each of the selected district were randomly selected as a second stage units by simple random sampling method. In summary, 72 clusters (59 rural and 13 urban slums) from the 20 districts of the states were randomly chosen. A house to house visit was made by trained Field Investigators (FIs) in these selected clusters. A minimum of 30 eligible persons were studied from each selected cluster. A total of 2023 (92%) participants out of enumerated persons of 2200 were consented (signature or thumb imprint) and participated in the study.A team of three field workers and a team leader were trained for data collection and management respectively. Field investigators were standardized with that of a final year Diplomate of National Board (DNB) fellow resident ophthalmologist (gold standard) and the inter-observer agreement in terms of Kappa statistics between both (for presenting VA and lens examination) was 0.88. At least 2-3 visits were made to the households. If an eligible person was not available in the house even after a third visit apart from the two visits in the morning and evening of the day, then such persons were categorized as non-respondents to the survey. Prior approval was obtained from Sankara Eye Foundation, India’s Institutional Review Board and the study has followed the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before interview and subsequent examination. Data collection was done in the selected clusters by house to house visits. Eligible persons in the household were interviewed about their age, gender, educational status (any formal education considered as literate), smoking status, history of cataract surgery (pseudophakia/aphakia), and details on systemic illness. As part of an interview, a pretested questionnaire was administered to elicit the barriers to uptake of cataract surgery from participants who did not utilize cataract surgical services despite noticed decreased in vision (VA<6/18). If more than one barrier was reported by a respondent, then the most important barrier as noted by the respondent was considered for analysis. Participants were deemed to be diabetic or hypertensive, if they were currently on medication and/or had a recent prescription from a certified physician.

4. Participant Assessment

- Presenting distance visual acuity (VA) was measured using the Snellen’s or illiterate E chart, in each eye separately in front of the house in the day light. After measuring VA, eye examination was performed in a shaded dark area of the house. All eyes with a VA<6/18 were examined with a torch to assess lens status. As part of the Community Outreach Services Program, the FIs were trained enough to identify the people with operable cataract and refer to the nearest camp site for further investigation by an ophthalmologist. They were also able to distinguish the patients between normal lens, lens opacity present, lens absent (aphakia) or intraocular lens implantation (IOL).

5. Statistical Analysis

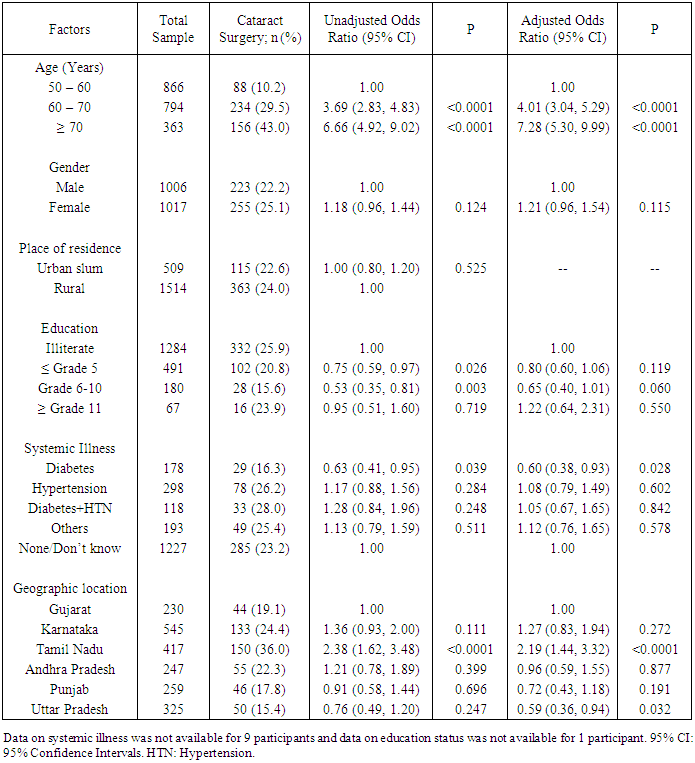

- Data were analyzed descriptively first. Categorical data analysis was carried out by using either χ2-test or Fisher’s test as appropriate. The unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) (with 95% confidence interval (CI)) of the cataract surgery (CS) were calculated for a comparison between different age group, gender, place of residence, education status, systemic illness and geographic location. A final multivariable logistic regression model included all of the variables with a p-value ≤0.20 obtained in the univariable logistic regression model. A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis.

6. Results

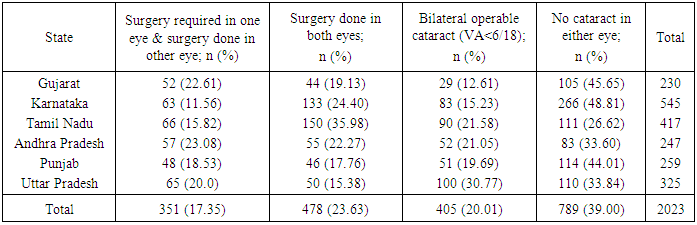

- A total of 2023 (92.0%) people out of 2200 enumerated were interviewed and examined. The mean age was 63.8±8.9 years (range 50-108 years). 50% (n=1017) of them were women. Table 1 describes the cataract surgery details either in one or both eyes and lens status in terms of bilateral operable cataract with presenting visual acuity <6/18 in the better eye and status of no cataract in either eye. A total of 478 (23.6%) participants (223 men and 255 women) had received cataract surgery (either pseudophakia/aphakia) in both eyes (Table 1); TN being the highest and UP being the least performer among the states (Table 1).

|

|

|

7. Discussion

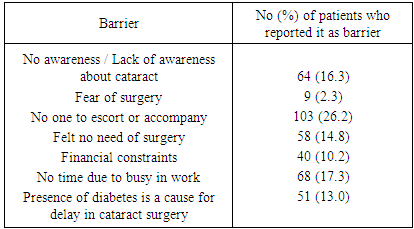

- The current study has identified behavioral barriers such as no one to escort and too busy with work as major dominant barriers for low uptake of cataract surgery in this population. In addition to these barriers, lack of awareness about the cataract problem was also a major barrier found in this study. On the other hand, presence of diabetes was also a barrier as patients with diabetes quite often need to postpone the cataract surgery. The study revealed that 13% of the patients did not utilize the cataract surgical services due to presence of diabetes as the condition did not come under control despite medication. This finding is comparable with a previously published report from an urban Pune, India which mentioned that presence of systemic illness being the third most barrier for the delay in cataract surgery in 17% of their studied sample. [5] Similarly, our finding is comparable to a study finding (18.2%) conducted in South Western Nigeria. [23] This is because, cataract in most instances is age-related and may coexist with other illness such as diabetes and hypertension, thus hampering such patients from seeking cataract services. Our study revealed that lack of awareness about cataract problem is also one of the significant barrier for low uptake of cataract services in the state of UP. This finding suggest that patients from UP is far behind in utilizing the cataract surgical services, which needs a concerted effort to improve the awareness levels about eye health in the community. The less utilization of cataract services in UP can be attributable to the principal barriers included lack of family support and failure to understand the need for surgery because of low awareness about eye health in the population in the state. This finding is in accordance with previously published reports. [6, 17, 20, 21] Education targeting entire families to eliminate these barriers and development of community support systems at the family level are required to achieve greater uptake of low-cost cataract surgery programs in rural India. In addition to this, there need an effort from government and NGO sector to improve the eye care infrastructure and sufficient man power to deal with the avoidable blindness due to cataract in UP. In this study, we found that there exists an association between presence of diabetes and CS both in bivariable and multivariable analysis. Persons with presence of diabetes had significantly lower odds of prevalence of CS. This could be due to the fact that the persons with diabetes are not fit enough to undergo surgery and hence are left un-operated. However, there should be a mechanism where these patients can be identified, be treated for diabetes and then should be operated upon. However, due to the popularity of small-incision phacoemulsification cataract surgery and its minimal complications, majority of the patients with diabetes are treated for blood glucose control at hospital and the same day cataract surgery is done. Visual impairment due to cataract restricts one’s ability to contribute to their families and communities, access information, socialize, maintain their health and earn. In our study, we found that 13% (n = 51) of the patient who need cataract intervention did not undergo surgery just because of presence of uncontrolled diabetes. This is a serious public health issue due to the fact that there is an epidemic proportion of growing diabetic population in India. Other major significant barriers to cataract surgery were no awareness about cataract problem and no time to go for health checkup due to busy in work. Older people should be educated about how to overcome the social and health related barriers to access eye care and to minimize the impact of visual impairment.Other reasons for low uptake of cataract surgical services in people with diabetes may be due to the complications of surgery especially in people with longer duration of diabetes. Studies have revealed that patients with uncontrolled diabetes are at a higher risk of experiencing complications during surgery, such as vitreous hemorrhage. Both small and large blood vessels are weakened by high blood sugar levels thus increasing surgical risk for diabetic patients. The most common postoperative complications in patients with diabetes were inflammatory reactions and bleeding: postoperative keratopathy, uveitis anterior serous and uveitis anterior fibrinous with posterior sinechia with worsening of post-operative vision. [7] Earlier studies have advised that phacoemulsification is the type of surgical procedure undertaken by an experienced surgeon especially in patients with diabetes and cataracts. This was because these patients often were found to have surgically miosis therefore this recommendation. [14, 15] Though our study is not designed to understand the diabetes complications in patients with cataract, however, these kind of complications are anticipated in patients with diabetes undergoing cataract surgery after their diabetes has been brought under control and therefore may require an attention to deal such postoperative complications. Nevertheless, the proper management of diabetes is required as in our study we have a noticeable proportion (13%) of the patients did not undergo cataract surgery due to uncontrolled diabetes. In our study, the major barriers for low uptake of cataract services were more often related to patient attitude (no one to accompany them, ability to manage with current eye sight and busy with work) (Table 3). These findings are in accordance with a previously published report from India. [16, 19, 21] However, our study finding related to fear of operation (2.3%, n = 9) is in contradiction to a study conducted earlier from rural South India. [13]The strengths of the present study are its representative sample studied with 92% response rate and a stringent standardized study procedures used, however, the limitations of the study are that a slit lamp examination with dilation of the pupil was not performed as the field workers were only trained enough to assess the lens status which might have lead to either under or overestimation of the operable cataracts. In conclusion, this study has found that presence of diabetes was a significant risk factor for low uptake of cataract surgical services. Low awareness about cataract is also a significant modifiable barrier for low uptake of cataract surgical services especially in the population of Uttar Pradesh. Awareness on eye health problems especially cataract and its available low-cost intraocular lens (IOL) governmental and non-governmental organization (NGO) surgery and free of cost NGO services available in the region needs to be improved. In addition, the attitude of the patients with cataract requiring surgery needs to be addressed. There needs to be initiates especially in the state of Uttar Pradesh to address the barriers to cataract surgical services and strengthen the existing community-based health-education programmes to improve the uptake of existing cataract services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Field Investigators in particular Mr Jafar Khan, Mr Kumar, Mr B Naga Babu, Mr B Saidulu, Mr H Manjunath and Mr Gaurav Kumar. The authors would like to also thank Administrators Mrs Manjula Devi, Mr L Srinivas Rao and Mrs Tripura Devi for coordinating the field work during data collection; data entry operator Mrs K Mahalakshmi for data entry assistance. Authors would like to thank all the participants who participated in this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML