-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2025; 15(1): 9-16

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20251501.02

Received: Jun. 17, 2025; Accepted: Jul. 15, 2025; Published: Jul. 23, 2025

Effects of Psychoeducation on Caregiver's Burden among Families of Patients with Schizophrenia in Nigeria

Olukorede Patricia Adisa1, Lasebikan Victor O.2, Ajibade Bayo Lawal3

1Department of Psychiatric Mental Health, Faculty of Nursing Sciences, LAUTECH College of Health Science Ogbomoso Oyo State Nigeria

2Department of Psychiatry, University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan Oyo State Nigeria

3Department Psychiatry Mental Health, LAUTECH, Ogbomoso Oyo State Nigeria

Correspondence to: Olukorede Patricia Adisa, Department of Psychiatric Mental Health, Faculty of Nursing Sciences, LAUTECH College of Health Science Ogbomoso Oyo State Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

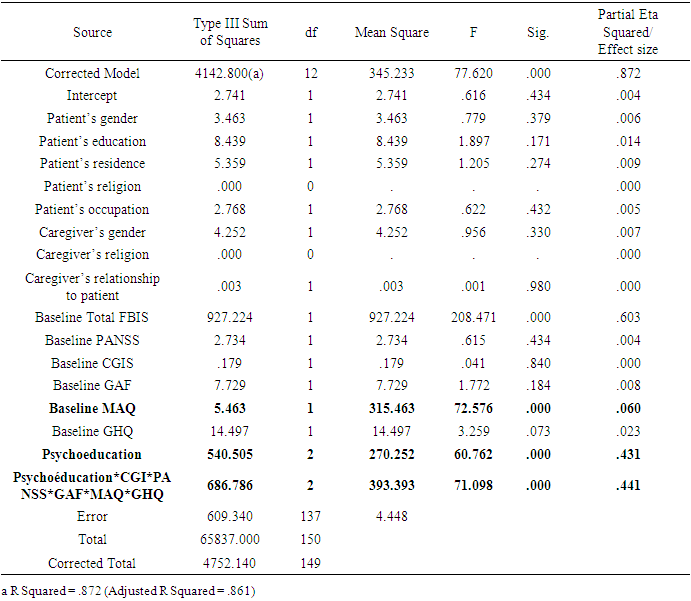

Background: Psychoeducation plays a significant role in the management of schizophrenia both in the management of the patients and family caregivers. Objective: The study examined the effects of psychoeducation on caregivers’ burden in relatives of patients with schizophrenia attending LAUTECH Teaching Hospital, Ogbomoso. Methods: The study was a randomized-controlled intervention design with 80 subjects, comprising schizophrenic patients and their families. The instruments used for the study include the Sociodemographic Questionnaire, Family Burden Interview Schedule (FBIS), Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ), Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12), Positive and Negative Symptoms Scale (PANSS) and the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGIS). Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0. Results: Caregiver's sociodemographic factors were associated with higher mean FBIS at baseline. The mean CIGS scores were significantly higher in the control group at 3 weeks and at 6 weeks, (p = 01, p = 0.04) respectively. The mean GHQ scores were also significantly higher in the control group at 3 weeks and at 6 weeks, (p = 0.003, p = 0.001. p < 0.001) respectively.Psychoeducation demonstrated a statistically significant treatment reduction in total FBIS score F(2, 137) = 60.7, p = 0.000, π2 = 0.431. Medication adherence (MAQ) demonstrated a statistically significant treatment reduction in total FBIS scores. F(1, 137) = 72.5, p = 0.000, π2 = 0.06. Conclusion: Psychoeducation was effective in significantly reducing caregivers’ burden in families of patients with schizophrenia. Medication adherence also had a relative contribution in reducing caregivers’ burden. It is recommended that nurses offer psychoeducation routinely to reduce caregivers’ burden on families of patients with schizophrenia.

Keywords: Psychoeducation, Caregivers, Caregiver's burden, Schizophrenia, Nigeria

Cite this paper: Olukorede Patricia Adisa, Lasebikan Victor O., Ajibade Bayo Lawal, Effects of Psychoeducation on Caregiver's Burden among Families of Patients with Schizophrenia in Nigeria, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 9-16. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20251501.02.

Article Outline

1. Highlights

- Psychoeducation documented for family caregivers of schizophrenic patients in developed countries is resource-driven, making it unsuitable for a resource-limited country like Nigeria. The transition of care for patients living with schizophrenia from hospital to home is a new trend of care that places a huge demand for care on family schizophrenia caregivers in terms of caregiving tasks.Given that patients with schizophrenia require prolonged care at home and in-hospital, family caregivers need to be psycho-educated for effective caregiving roles.

2. Introduction

- Caregiving burden is higher among immediate family members than among other caregivers who face illness–specific burdens of feeling powerless, fear of marital stress, and great financial drainage on the family purse and family roles. [1-3] In developing countries such as Nigeria, caregiver’s burden is not related to deinstitutionalization because most mentally ill patients live with their families while existing studies found that about 65% of discharged mentally ill patients lived with their relatives, and 40% to 90% of schizophrenic patients lived with their family members. [4-7] Caregiver’s burden is due to a high unmet need, in the treatment of mental disorders, chronic and recurrent nature of mental illness, poor National health policy, medical co-morbidities, stigma and lack of services for disadvantaged groups [8,9] leading to widespread disabilities. [7] In Sub-Saharan Africa, studies on the caregiver burden on mental disorders have failed to differentiate the subjective and objective burden of the disorder experienced by the caregiver. [10-12] It is generally thought that emotional support and help from family members, friends, or healthcare providers will improve the patient’s compliance with medication. [13,14] Caregiver education on the importance of compliance with medications and their role in caregiving helps reduce relapse and alleviate the burden of care. [15] It improves social functioning and reduces the cost of care for schizophrenic patients. [16] The term ‘‘psycho-education is a behavioral therapeutic concept that primarily comprises of brief discussion about the nature of the illness, problem-solving training, communication training, and self-assertiveness training, which could be delivered as a group or individual therapy. [17,18]In Nigeria, the ratio of registered nurses to the population is 100/100,000. [20] For reasons of the inadequacy of health personnel, healthcare professionals rely on family caregivers to provide technologically-driven, formal and informal care for patients with schizophrenia, although family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia play this significant role, they appear to be "hidden patients" that are often neglected whereas they also need support during the caregiving process. [21] Psychoeducation serves as a means of providing respite during critical moments of caregiving and therefore prevents caregivers from becoming patients in the immediate future. This is achieved through the provision of adequate and timely the caregiver about schizophrenia and its contributory roles to the burden of care. [17] This intervention study assessed the effects of psychoeducation on caregivers’ burden among relatives of patients with schizophrenia in Nigeria.

3. Methodology

- Study Design The study was a double-arm blinded randomized-controlled pre and post-interventional study involving experimental and control groups.Study Population/SiteThe study population is the principal caregivers who accompany patients with schizophrenia to the outpatient clinic of LAUTECH Teaching Hospital, Ogbomoso over 6 weeks constituted the potential respondents.The average weekly turnover rate of new patients with schizophrenia at the outpatient psychiatric clinic of LAUTECH Teaching Hospital, Ogbomoso is about 40 patients, and the clinic is on every Tuesday and Thursday of the week. Therefore, about 160 patients were seen monthly and approximately 240 patients (the sampling frame) in 6 weeks.InstrumentsPatient and Caregiver Socio-Demographic and Clinical Data: This was obtained using a predesigned socio-demographic and clinical data sheet which includes the patient’s age, gender, education, income, employment status, marital status, number of children, areas of residence, duration of illness/care and number of hospital admissions.Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): This was used to evaluate the presence, absence and severity of Positive, Negative and General Psychopathology Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Each subscale contains individual items. It has 30 items, which are arranged as seven positive symptom subscale items (P1 - P7), seven negative symptom subscale items (N1 - N7), and 16 general psychopathology symptom items (G1 - G16). All 30 items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = absent; 7 = extreme). Thus, the potential range of scores on the Positive and Negative Scales is 7 – 49, with a score of 7 indicating no symptoms. The potential range of scores on the General Psychopathology Scale is 16 – 112. PANSS Total score minimum = 30, maximum = 210. It takes an average of 45 minutes to administer the scale. The inter-rater reliability is high (between 0.73 and 0.88). Test-retest reliability of the Positive, Negative, and General Psychopathology Symptoms are also good with a correlation range of .77 to .89.Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale: This is a 100-Point single rating scale used by a clinician to determine the overall functioning of a patient during a particular period. The GAF is viewed as a composite of three major domains: Social functioning, Occupational functioning, and Psychological functioning. The GAF is derived from the Global Assessment Scale (GAS), which has established psychometric properties. Joint reliability on the GAD and the GAF across several studies ranged from 0.61 to 0.91 indicating fair to excellent agreement (Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss, and Cohen, 2019). It has also been used in Nigeria (Lasebikan and Ayinde, 2020). The functional level of the family caregiver patient over the period before and after the intervention was used to assess GAF.Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Scale: The CGI is a 3-item observer-rated scale that measures illness severity (CGIS), global improvement or change (CGIC) and therapeutic response. The CGI is rated on a 7-point scale, with the severity of illness scale using a range of responses from 1 (normal) through to 7 (amongst the most severely ill patients). CGI-C scores range from 1 (very much improved) through to 7 (very much worse). Treatment response ratings should take account of both therapeutic efficacy and treatment-related adverse events and range from 0 (marked improvement and no side-effects) and 4 (unchanged or worse and side-effects outweigh the therapeutic effects). Each component of the CGI is rated separately; the instrument does not yield a global score (Guy, 2020).Family Burden Interview Schedule (FBIS): It is a standardized semi-structured instrument for assessing family burden. The 26-item instrument has two categories: (a) objective burden, which has six parts that assess financial burden, disruption of routine family activities, disruption of family leisure, disruption of family interaction, effect on the physical health of others and effect on the mental health of others, and (b) a subjective part. Each item is scored on a three-point scale, viz severe burden (completely) - 2, Moderate burden (partially) – 1 and no burden (not at all) - 0. It has a high internal consistency demonstrated by a significant Cronbach α of between 0.62 and 0.82 for each item. The intra-class correlation coefficient for the total score of Y-FBIS was 0.84 at 95% confidence interval. The test-retest reliability of individual scales ranges from 0.78 to 0.87 and 0.83 for the total objective scale score. Convergent validity was shown by the significant positive correlation (r = 0.83) between the objective burden score and the subjective burden score of YFBIS. This instrument was used in different studies among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia.General Health Questionnaire – 12 Item Version (GHQ – 12): This screening instrument measures the current mental state of an individual by focusing on the inability to carry out normal functions and the appearance of a new distressing experience (Goldberg and Williams, 2020). The bimodal response scale was used in this study. Respondents with a score of 3 and above were described as GHQ positive (that is probably distressed emotionally) and those with a score below 3 termed GHQ negative.Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ): This is a four-item self-report scale. Each item on the MAQ measures a specific medication-taking behavior. It is available in two versions, the first being the original versions with a binary response option (no/yes scored 0 and 1 respectively) and with mean scores ranging from 0-4. A cut-off value of MAQ mean score ≥2 and <2 labels the patient as medication adherent or non-adherent respectively. This version will be used in this study. The second version is a five-point response version (never/rarely/sometimes/often/always) having scores that range from 0-16, with higher scores indicating non-adherence. The word “careless” may be misunderstood as not keeping medication safe and may also be derogatory in meaning. Psychoeducation The principle of psychoeducation as demonstrated by Sarkhel et al [17] used in the study includes;1. Briefing the Patient about the Illness: This element of psychoeducation involves educating the caregiver about the patient’s illness, the definition of the caregiver’s burden, the cause, presentation and consequences. 2. Problem-Solving Training: Problem-solving training involves educating the caregiver on the various ways they can cope with the various problems associated with caregiving. It entails encouraging them to accept the reality of the patient’s illness and dispel any myth associated with it. It also involves educating them on various coping strategies, helping them overcome pressure, and worries, seeking treatment with alternative practitioners, and encouraging them to join social support groups. People who confronted stress with problem-solving and behaviour-modifying approaches have been found to have a better quality of life while coping by denial has been associated with a poor quality of life. 3. Communication Training: Communication training in psychoeducation deals with encouraging caregiver to clarify any information about their disease with their healthcare providers. It also involves encouragement of disclosure of the illness where and when necessary. 4. Self-Assertiveness: This involves improving self-esteem, developing self-confidence as well and sharing positive information when necessary.Sample Size Determination The minimum sample size for the study was based on the sample size calculation for a randomized-control trial when the endpoint was quantitative. According to Lasebikan and Ayinde (2020) [18], the prevalence of caregiver burden among families of patients with schizophrenia in a Nigerian population was 85.3%. It was assumed that the intervention would result in the treatment group having a 30% (0.3 better knowledge of the intervention content than the control group. At a 5% significance level and a power of 90%, the sample size, with 20% attrition equals the minimum sample size of 77 in each group.Procedure At baseline, 150 dyads of consecutive patients who met ICD 11 criteria for schizophrenia and other inclusion criteria together with their respective family caregivers were randomized into the treatment group and control groups respectively. The first dyad was randomly selected using a table of random numbers. Patients were matched by age range and duration of illness.Intervention This is divided into baseline assessments (T0), 3 weeks assessments (T1) and 6 weeks assessment (T2). CASE GROUP: The case or intervention group was family caregivers of patients (diagnosed with schizophrenia) who received psychoeducation. CONTROL GROUP: The control group consisted of family caregivers of patients ((diagnosed with schizophrenia)) who did not receive psychoeducation.Baseline Assessments (T0)At baseline, sociodemographic and clinical assessments were carried out using the sociodemographic questionnaire, PANSS, GAF, GCIS, GHQ-12, MAQ and the FBIS collected from both patients and their respective caregivers. Following this, caregivers of patients with schizophrenia received treatment (olanzapine or haloperidol) as usual as ordered by the managing psychiatrist in both groups. In addition, caregivers in the intervention group received structured psychoeducation delivered by the researcher and research assistant.T1 (3 weeks after baseline assessment)All caregivers of patients (intervention and control groups) were assessed using the PANSS, GAF, GCIS, GHQ-12, MAQ and FBIS. The allocator, caregiver of patients’ dyads and assessors were blind to the groups. This was aimed at observing the changes in the variables when compared with that collected at baseline before the general health talk and psychoeducational interventions. After the assessments, participants in the control arm were then randomly assigned to a control group, control group A and control group B by alternate method. The methodological approach was to minimize bias in the control group.T2 (six weeks after baseline assessments)During this phase, no further intervention was given to any group. At this stage, a final assessment was carried out using the PANSS, GAF, GCIS, GHQ-12, MAQ and the FBIS.Ethical Approval Approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical and Review Committee of LAUTECH Teaching Hospital, Ogbomoso Oyo State Nigeria.Data AnalysisData were presented using both descriptive and inferential statistics. For all the outcome variables, parametric methods were used for their analysis. Within-group comparisons were carried out using paired t-tests and between-group comparisons were carried out using independent t-test. Mc Nemmar’s Chi-square was used to compare baseline sociodemographic characteristics.To determine the impact of the intervention (psychoeducation) on FBIS, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used using baseline caregivers and patient’s sociodemographic data, baseline GHQ, baseline GAF, baseline MAQ, Baseline CGI-S and baseline FBIS before randomization as covariates. The effect size of the intervention was determined from the SPSS output as Partial Eta Squared. All analyses were set at a level of significance of < 0.05, 95% CI, and were carried out using the SPSS version 22.0.

4. Results

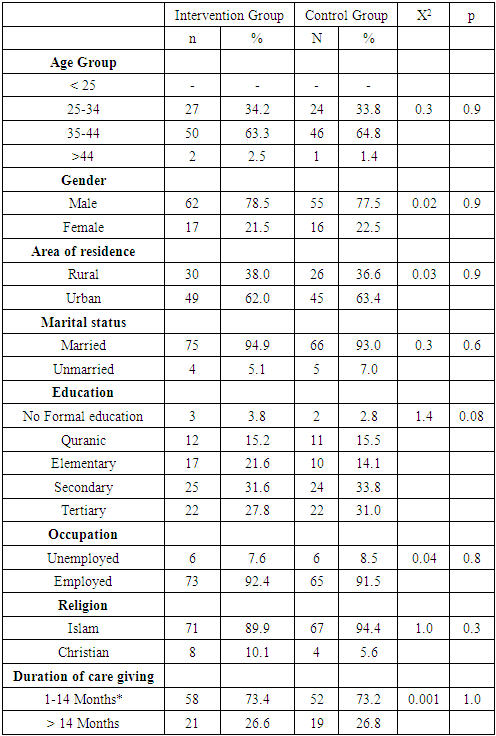

- A total of 150 eligible subjects were recruited for the study. These patient/caregiver dyads were randomly allocated into intervention (N= 79) and control groups (N= 71). There were no significant differences in the sociodemographic characteristics of both groups. Table 1.

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

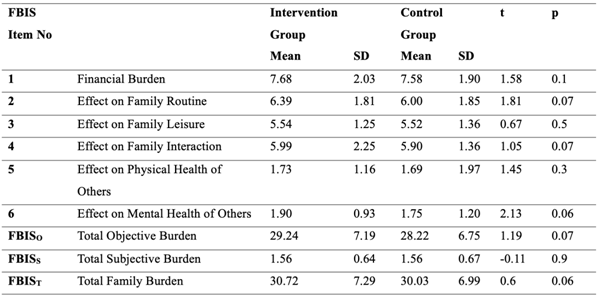

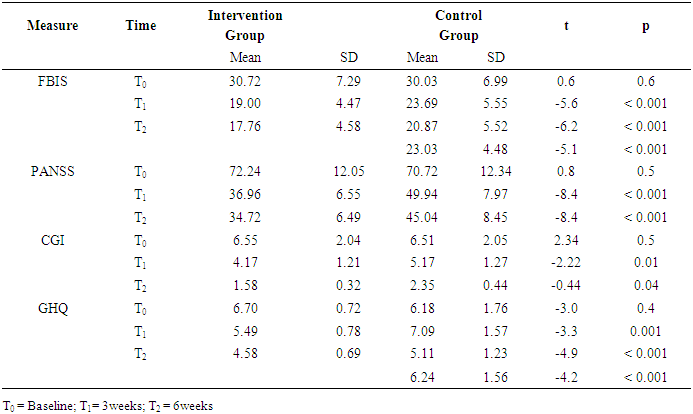

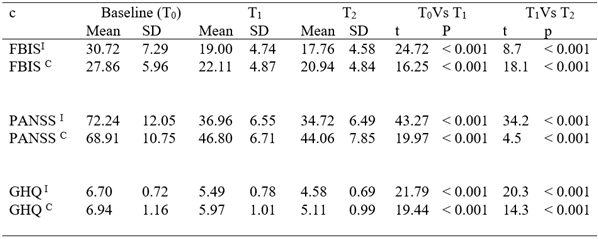

- The present study shows that psychoeducation led to a significant reduction in the family burden at 6 weeks after controlling for baseline family burden, psychological distress, severity of psychopathology, patients’ and caregivers’ sociodemographic factors at baseline. This shows that the intervention was very effective.Caregivers experienced significant burden in the area of financial burden, followed by family routine and interaction. Results similar to this have been reported [18,23,24,25] in the western part of Nigeria despite differences in cultures. The high level of family burden is not unexpected considering the continuing salience of family out-of-pocket expenses for the care of patients in Nigeria where the National health profile is still poor. [26] The result is also in consonance with that obtained in Kenya in which disruption of patients’ wandering, aggression and refusal to go to the hospital contributed to disruption in family routine. [27]However, the total family burden score obtained in the current study is somewhat higher than those reported by Udoh et al [28] in Western Nigeria using Zarit family burden assessment. This may suggest a geographical or ethnic variation in the psychosocial circumstances of Northern and Southern Nigeria, or maybe a reflection of a family burden on a background of emotional problems that could be attributed to the perennial terrorist activities in the region.At baseline, in both intervention and control groups, there was a direct relationship between the total burden score, GHQ score and the severity of psychotic symptoms as shown by the PANSS score. This relationship continues through the 3rd and 6th week of the study. These results are in support of the systematic review by Karambelas et al [29] and Udoh et al. [28]There was a positive correlation between caregivers’ burden, psychological distress in caregivers and the severity of the psychopathology at all stages of the study similar to past reports. [18,30] This is because antipsychotic use led to a reduction in the severity of schizophrenia symptoms and a consequent reduction in burden caregivers. This implies that prompt diagnosis and antipsychotic intervention among patients with schizophrenia are effective in reducing caregiver burden. This is because antipsychotic medication led to a reduction in PANSS score and CGIS. It has been shown that patient’s symptoms and behavior are the leading source of burden of care among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and that antipsychotic use significantly reduces caregivers’ burden. [1]The results of the interactive effect of clinical response (CGIS), severity of psychosis (PANSS), level of functioning (GAF) medication adherence (MAQ), and psychological distress (GHQ) on caregivers’ burden (FBIS) yielded a good effect size. The results also show that medication adherence (MAQ) demonstrated a statistically significant treatment reduction in total FBIS score although, the effect size was small. Noting that the relative contribution of medication adherence produced a very small effect size and the effect size produced from the interactive effects of clinical response (CGIS), severity of psychosis (PANSS), level of functioning (GAF) and medication adherence (MMAS) was more or less the same.Psychoeducation is effective in reducing the burden experienced by caregivers of patients with schizophrenia by changing the caregivers’ cognitive representation of psychosis. [32] The psychoeducation received by this group is said to be responsible for this reduction in the psychotic symptoms and burden of care. This finding is similar to that observed by other similar interventional studies. For example, Mueser et al. [33] also found that psychoeducation on schizophrenia patients and their caregivers leads to a significant reduction in the burden experienced by the caregivers. It has also been found that caregiver education helps patients to adhere to antipsychotic medications which ultimately contributes to a decrease in symptomatology. [34]

6. Conclusions

- The study demonstrated a significant reduction in caregivers’ burden resulting from psychoeducation offered to both the patient and the caregiver in the same setting to facilitate dyad-cohesion, and simultaneous medication adherence in the patient, which in turn led to a reduced burden of care. Psychoeducation has been shown to play a significant role in reducing the burden experienced by caregivers of patients with schizophrenia which can be provided in the form of written leaflets, videos, or web-based materials and is very applicable with the increased use of digital technologies therefore, findings from the present study underscore the need for family-based psychoeducation as a catalyst for pharmacotherapy.

Limitations of the Study

- This is a hospital-based study, thus all the subjects recruited in the study were chosen from the psychiatric out-patient clinic only. Those who are economically buoyant may seek treatment elsewhere. Secondly, stigmatization associated with mental health facilities may influence the nature of patients utilizing the services of the hospital.The result of the study showed that most of the subjects are from urban areas, which may be that the economic situation made it difficult for patients from rural areas to access the hospital; however, this result may not be a clear representation of the population at large which leaves room for future multicenter study to improve the generalizability of the findings.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML