-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2023; 13(1): 12-24

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20231301.02

Received: May 28, 2023; Accepted: Jun. 21, 2023; Published: Jun. 26, 2023

Analysis of the Critical Thinking of Nursing Students in Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR)

Joman J. Baliton1, Mark Job G. Bascos2

1School of Graduate Studies, Saint Mary’s University, Bayombong, Philippines

2School of Advanced Studies, Saint Louis University, Baguio City, Philippines

Correspondence to: Joman J. Baliton, School of Graduate Studies, Saint Mary’s University, Bayombong, Philippines.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Nursing students need to develop critical thinking skills early on while undergoing educational preparation and clinical training to equip them provide safe and quality patient care. Using a mixed-method approach, this study was undertaken to determine the level of critical thinking among students, determine which variable among the dimensions do students have the greatest involvement, construct a mathematical model that explains critical thinking among nursing students through a linear combination of the variables in the dimensions of critical thinking and their profile variables, and list enhancers and barriers on critical thinking. Electronic questionnaires were administered to nursing students in the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR). Utilizing the researcher-made Critical Thinking Instrument for Nursing (CTIN), which was tested and found to be a valid and reliable instrument to measure the level of critical thinking among nursing, it was revealed that students are generally involved in developing their critical thinking. Among the four dimensions of critical thinking, students are most involved in developing their disposition skills followed by critical thinking criteria. Students are least involved in developing cognitive skills and strategies which are equally possessed by students. The level of critical thinking can be explained by a linear combination of its four dimensions, highest educational attainment of mother, and occupation of father. Most learners identified application of skills and keeping up with trends and issues as enhancers in developing critical thinking. On the other hand, numerous school requirements were found as a barrier in developing critical thinking. It is suggested that programs for nursing students should be considered for the development of nursing students’ critical thinking by assisting them in reinforcing enhancers, improving critical thinking indicators where students are least involved, and addressing barriers to critical thinking development.

Keywords: Critical thinking, Cognitive skills, Disposition skills, Strategies, Criteria, Exploratory factor analysis

Cite this paper: Joman J. Baliton, Mark Job G. Bascos, Analysis of the Critical Thinking of Nursing Students in Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR), International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2023, pp. 12-24. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20231301.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- One of the main dilemmas encountered in medical fields, including the nursing profession, is the gap between theory and practice [1]. Although students have passed theoretical units in the clinical environment, they do not get their scientific expertise [1]. That is, deficiencies between theory and practice have been recorded. [2] exemplify critical thinking to address the gap between theory and practice. Especially that critical thinking skills do not significantly develop when they acquire a nursing degree [3]. It can be deduced from the claims of [3, 4], and [1], that nurses might not fully develop their skills in nursing, including critical thinking. Relative to this, high rates of error and injury have been reported concerning patients' safety worldwide [4]. In addition, [5] have mentioned that various problems and problematic situations related to patient's symptoms, therapy, and daily care of different levels of importance and complexity have been faced by nurses. The present health care settings require nurses to resolve these problems effectively, but nurses lacked problem-solving skills [6,7].Nurses need to possess creativity, analytical, and critical thinking skills in the 21st century's nursing environment [5]. Thus, there is a need to start developing these skills during their educational learning experiences in college as nursing students. It was revealed by [8] that nursing students should have been active learners and critical thinkers in providing safe patient care in this generations' technologically sophisticated environment. In corroboration to this, [9] mentioned that skills vital for safe nursing practice in this generations' diverse and complex health care environment include the ability to question existing practices, make decisions and think critically.[10] listed critical thinking skills and habits of the mind for nursing. Critical thinking skills include analyzing, applying standards, discriminating, information seeking, logical reasoning, predicting, and transforming knowledge. On the other hand, habits of the mind composed of confidence, contextual perspective, creativity, flexibility, inquisitiveness, intellectual integrity, intuition, open-mindedness, perseverance, and reflection.According to [8], critical thinking is an individual's rational and reflective thinking on what to do or believe. As mentioned by [11], critical thinking is also a cognitive process that comprises a reasonable analysis of information to aid decision-making, judgment, and reasoning. Likewise, critical thinking is described as a cognitive-motor that drives problem-solving and decision-making [12]. Critical thinking is explained by [13] as a disciplined process of conceptualizing, applying, evaluating, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating gathered information based on observation, experience, and reasoning. This is a voluntary contribution to a process that includes reflecting, recognizing, and assessing assumptions, understanding meaning, and applying thinking skills such as perception, reason, and decision [14]. Critical thinking in nursing is defined as consequential, purposeful, and rational thinking that depends on the needs of patients and is based on professional standards and policies [15]. Aside from that, critical thinking is a complicated self-regulatory process that encompasses contextual, criteriological, methodological, conceptual, and evidential factors in reaching decisions and outcomes in evaluating, interpreting, and conducting complete analyses of information. Core elements that emphasize a critical approach to the nursing process can be inferred to affirm experiences as emancipatory and point out the significance of reflection and communicative action as organizational frameworks for nursing intervention [16].[17] defines critical thinking in nursing as purposeful, informed, result-focused thinking centered on nursing process values, problem-solving, and empirical methods involving opinion formulation and decision-making based on evidence. Moreover, she assessed level of critical thinking as how an individual demonstrates or involves oneself in developing dimensions of critical thinking. An earlier literature of [18] defines critical thinking as kind of thinking that involves individual in a thoughtful and effective thinking task, developing skills like when a person calculate likelihood, formulate inferences, make decisions, and solve problems. For the purpose of this study, the level of critical thinking is manifested through active involvement of student nurses in developing dimensions of critical thinking. In line with critical thinking cognitive skills, dispositions have been identified as a mental attribute incorporated into one's beliefs or actions [19]. Disposition is defined by [20] as unswerving willingness, inclination, motivation, and an intention to be involved in critical thinking. [21] observed that critical thinking is marked by a consistent internal drive to solve challenges and make choices by critical thinking.Some of the instruments developed in measuring critical thinking are the California Critical Thinking Skills Tool (CTTST) and California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CTTDI). Along with these, a multitude of tools were developed in order to assess the level of critical thinking like Cornell Critical Thinking Test (CCTT), Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (WGCTA), Nursing Critical Thinking in Clinical Practice Questionnaire, Slovak Version of Critical Thinking Test and Ennis-Weir Critical Thinking Essay Test. Researchers have observed challenges with the construct of critical thinking, including the lack of a conceptual explanation or description to utilize as a starting point and the absence of a designed assessment tool to measure critical thinking skills among nursing students [11]. Other than this, [22] accentuated that CCTST and WGCTA are not specific tools in measuring critical thinking in nursing. It can be deduced that the dimensions of critical thinking stressed in the mentioned literature were the disposition skills and cognitive skills or behavioral competencies in improving critical thinking. Interestingly, these cognitive and disposition skills are paired with critical thinking strategies and criteria in the critical thinking conceptual model by [23,24,25,26,27,28,29], where they are part of dimensions of critical thinking. For this reason, the researchers adapted this framework to develop a tool in measuring the level of critical thinking among nursing students.Furthermore, assessment tools mentioned earlier were found to have a reliability value below and beyond acceptable Cronbach's alpha coefficient. One of the underpinnings dealt with this study was the development of a questionnaire applicable to nursing students in the Philippine setting. Apparently, [30] has argued that an ever-changing social reality means that theories need to be continually revised, modified, or abandoned, even though they are deemed right in the current phenomena. According to the adapted framework, this assumption led the researchers to explore the instrument used to assess the level of critical thinking among nursing students. Using this context of the study, various authors' perspectives on the instruments used to evaluate the level of critical thinking among nursing students were used to build the research instrument in evaluating the level of critical thinking among nursing students.As previously stated, the rising complexity of technological advancements and patient care, which has generated obstacles in decision making, has prompted medical researchers to conduct research, notably in the development of critical thinking. Internationally, [31] found that primary baccalaureate nursing students obtained relatively lower critical thinking scores than accelerated second-degree students. Factors in the critical thinking disposition and skills of intensive care nurses in Turkey were investigated by [32]. There was no statistically significant difference between the mean CTTDI scale ratings when nurses were classified by their age, study year, socioeconomic status, and educational status. This study also associated scores in Critical Thinking Instrument for Nursing (CTIN) with nursing students' sex, age, religion, birth order, sibling size, socioeconomic status, highest educational attainment and occupation of mother and father, and school type. Critical thinking among nursing students was explored by [33] through cross-sectional analysis. A lack of critical thinking skills among nursing students was discovered in the study. Their analysis used exclusively quantitative research approaches, while a mixed-method approach was used in this study. In addition, profile variables were explored and compared to their study that centered solely on analytical thinking skills. [34] had conducted a qualitative study trying to explore the definition of critical thinking. It was found that definitions and identified enhancers and barriers are consistent and aligned with the current nursing definitions. The present study looked into critical thinking enhancers and barriers, which can be in corroboration with the findings of [34]. In Western Asia, specifically in Iran, another report on critical thinking was investigated by [1]. Critical thinking was discussed in comparison to clinical competence, and it was discovered that a positive correlation existed between the two. CCTDI was used to test nursing students' critical thinking while this study developed a questionnaire in assessing nursing stduents’ level of critical thinking. Another study in Iran was conducted by [4], who examined critical thinking skills among junior, senior, and graduate nursing students. [35] have analyzed the demographic profile of students in forecasting their critical thinking disposition. In the context of constructing a mathematical model in forecasting critical thinking, their work and this research are the same, whereas their study was limited to disposition alone, this study is extended to the level of critical thinking where all four dimensions along cognitive skills, disposition skills, critical thinking strategies and critical thinking criteria are considered. Another research utilizing mathematical modeling was conducted by [36], where the relationship between school administrators' creative and critical thinking dispositions related to problem-solving skills and decision-making styles was investigated. In determining the patterns between variables, the study hypothesized a model and was tested by sequential equation modeling, particularly an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). This research technique was also used in this research, where it underwent an exploratory factor analysis on the construction of the research instrument, called Critical Thinking Instrument for Nursing (CTIN). This was done to evaluate the variables correlated with the level of critical thinking reflecting the study's locale and current phenomena aligned with the pragmatic philosophy of this study. In addition, this was used to evaluate an equation that, in general, tests the level of critical thinking in nursing.In the Philippines, [37] studied the relationship between exposure to case studies and critical thinking skills. Their study and this research deal with nursing students where the same non-random sampling techniques were used. Also, [38] conducted research on critical thinking among nursing students to design instructional strategies, while this study was used to develop mathematical models that represent critical thinking among nursing students. In reference to previous works of literature and studies, this study was conducted among nursing students in order to assess the dimensions of critical thinking, particularly the cognitive skills, disposition skills, critical thinking strategies, and critical thinking criteria, together with enhancers and barriers that needed to be reinforced and to address educational deficiencies. According to [4], these are expected to be developed as they graduate, and this shall serve as a basis in making appropriate decisions in the clinical setting. Specifically, this study explored the level of critical thinking among nursing students using the Critical Thinking Instrument for Nursing (CTIN) and also to evaluate which dimension of CTIN students are more actively involved in. Likewise, this study was designed to determine statistically if there is a significant relationship and a linear combination of profile variables and dimensions of CTIN as a predictor of nursing students' level of critical thinking. This study also sought to identify the enhancers and barriers that influence students’ critical thinking. In the conduct of this study, a pragmatic approach was adapted by the researchers. This is in line with the claim of [39] that the spectrum of phenomena explored by nursing research is so diverse that a pragmatic approach is required to advance the understanding of the discipline. This study was conducted to determine the level of critical thinking among nursing students of the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR), identify dimensions where students have the greatest involvement, construct a mathematical model that explains critical thinking, and list enhancers and barriers to developing critical thinking.

2. Research Objectives

- This study was conducted to determine the level of critical thinking among nursing students of the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR), identify dimensions where students have the greatest involvement, construct a mathematical model that explains critical thinking, and list enhancers and barriers on developing critical thinking. Specifically, it attempted to address the following objectives:1. To determine the level of critical thinking among nursing students, particularly in the following dimensions:a. cognitive skills;b. disposition skills;c. critical thinking strategies; and d. critical thinking criteria.2. To identify whether there is a significant difference among dimensions of critical thinking where nursing students have the greatest involvement.3. To test if there is a significant relationship among nursing students' profile variables and dimensions of critical thinking.4. To explore if there is a significant amount of variation in nursing students’ critical thinking skills that can be explained by a linear combination of the profile variables and dimensions of critical thinking. 5. To list enhancers and barriers that influence nursing students’ critical thinking.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

- In achieving the objectives of this study, the researchers employed a mixed-methods approach. In the quantitative approach, the descriptive-correlational design was utilized. This design was applied in determining the level of critical thinking skills of nursing students in terms of the indicators and dimensions of Critical Thinking Instrument for Nursing (CTIN), identifying which dimension of CTIN do nursing students has the greatest involvement, and exploring the statistically significant relationship among nursing students’ profile variables and dimensions of CTIN. Descriptive-predictive research design was used in determining the amount of variation in nursing students’ critical thinking skills that can be explained by a linear combination of the profile variables and dimensions of CTIN. In the qualitative approach, the survey method was used to identify the enhancers and barriers listed by nursing students through an open-ended questionnaire. Descriptive type of qualitative research was used to understand identified enhancers and barriers.

3.2. Respondents

- A total of 473 students in the Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) program from three universities and colleges in the Cordillera Administrative Region were chosen for the study's first phase, which involved the development of a tool for measuring nursing students' critical thinking (CAR). The overall number of participants per year level from these nursing schools is as follows: Year 1: 150 students, Year 2: 120 students, Year 3: 103 students, and Year 4: 100 students.The second phase of the research was designed to expand the sample size and diversify the participants following the successful completion of the pilot study. 1,700 Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) students from ten universities and colleges in the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) who were not a part of the first phase were included in this phase. According to the number of students in each year level, Year 1 had 493 students, Year 2 had 437, Year 3 had 381 students, and Year 4 had 389 students.

3.3. Instrumentation

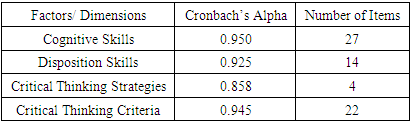

- In the conduct of the pilot study, the Critical Thinking Instrument for Nursing (CTIN) was utilized. The CTIN is a researcher-made instrument which is founded on literature and studies and aligned with the conceptual framework of the study. This instrument is a 4-point Likert scale which is composed of items covering the four dimensions of critical thinking: (a) cognitive skills, (b) disposition skills, (c) critical thinking strategies, and (d) critical thinking criteria. There are indicators for each dimension of critical thinking mentioned above. Under cognitive skills, there are six variables: the analysis, interpretation, inference, explanation, evaluation, and self-regulation. On the other hand, disposition skills are composed of six indicators which are open-mindedness, inquisitive, truth-seeking, analytical, systematic, and self-confident in reasoning. On the critical thinking strategies, four indicators have been identified. These are evaluated through individuals' questioning techniques, engagement in small group activities, attendance in role-playing activities, and participation in debates. For the critical thinking criteria, eight indicators have been included. These are clarity, precision, relevance, depth, fairness, accuracy, logicalness, and completeness. The scale determined the level of critical thinking of nursing students namely: greatly actively involved; actively involved; somewhat actively involved; and not involved. In the conduct of the main study, the instrument used was a survey questionnaire divided into three parts. The first part is the profile of the respondents, specifically their sex, age, religion, birth order, sibling size, socioeconomic status of the family, school type, year level, and highest educational attainment and occupation of parents of nursing students.The second part is the CTIN which is the instrument developed in the first phase of the study. In order to develop the questionnaire specially designed for nursing students, the researchers have conducted a literature review. Experts in nursing and proficient in designing assessments served as evaluators for the face and content validity of the questionnaire. CTIN had an item-level content validity index of 1.00. On the other hand, the internal consistency of each dimension or factor of the questionnaire is reflected in Table 1.

|

3.4. Data Analysis

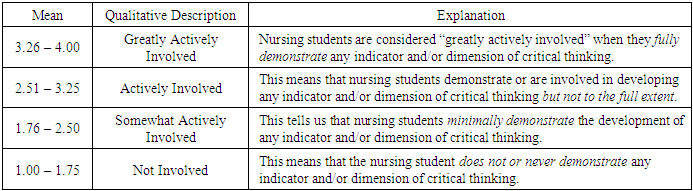

- For the first objective, the level of critical thinking among nursing students, particularly in developing dimensions of critical thinking and its indicators, was presented in tabular form utilizing mean and its qualitative description. The following scale presents the level of critical thinking together with its description.

|

3.5. Ethical Considerations

- Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the research ethics committee at Saint Louis University (Approval Certificate No. SLU-REC 2021-013). The study adhered to internationally recognized ethical guidelines for conducting research involving human subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study. Confidentiality and anonymity of participants' data were strictly maintained throughout the research process.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Level of Critical Thinking of Nursing Students

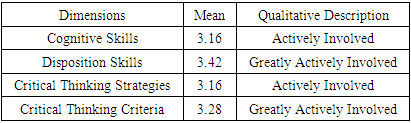

- One of the objectives of this research was to determine the level of critical thinking of nursing students of the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR), on its four dimensions, using the researcher-made instrument. Nursing students’ level of critical thinking in these dimensions are reflected in Table 3.

|

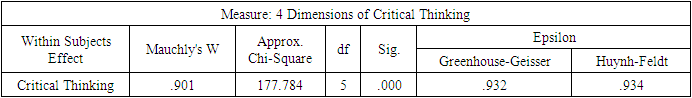

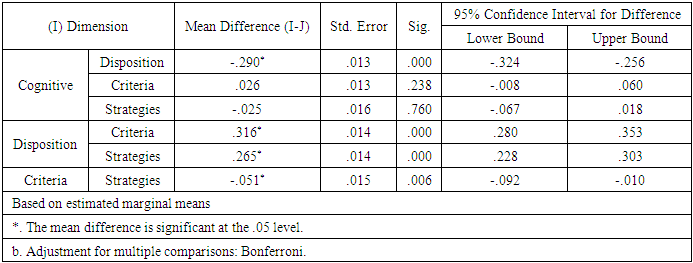

4.2. Significant Difference in Dimensions of Critical Thinking

- The researcher has identified if there is a significant difference in the level of critical thinking of nursing students in general. In more particular, this study identified which dimension where nursing students are greatest involved and least involved in developing their critical thinking. Certain assumptions should be met to determine whether the level of critical thinking of nursing students differs significantly. This includes homogeneity-of-variance-of-difference as determined by Mauchly's Test of Sphericity and tests of within-subjects effect. Table below shows the computed p-value on Mauchly's Test of Sphericity in comparing four dimensions of critical thinking.

|

|

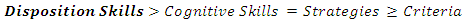

BSN students of CAR possess dimensions of critical thinking with different scores obtained. In terms of dimension where nursing students have the greatest involvement, developing disposition skills ranked the highest. It can be noted that students are most involved in improving themselves in being open-minded, inquisitive, and being fair. As earlier revealed, students are greatly actively involved in developing almost all indicators of disposition skills. Next to disposition skills is the dimension of cognitive skills. The inequality may suggest that nursing students have a higher level of critical thinking in terms of disposition skills than their cognitive skills. In like manner, students have a lower level of critical thinking in terms of cognitive skills than in their disposition skills. Further, students are more engaged in showcasing indicators or the sub-dimensions of disposition skills (open-mindedness, inquisitiveness, and fairness) than involving themselves in indicators or sub-dimensions of cognitive skills (analysis, interpretation, inference, explanation, evaluation, self-regulation, and analytical). The analysis tells us that there is a probability that nursing student does not equally showcase or engage themselves in being open-minded and analytical as an example. Compared to critical thinking strategies, the cognitive skills dimension appears to have no statistically significant difference. Nursing students, in other words, are equally engaged in these two dimensions of critical thinking. Meaning, when a student improves himself with his cognitive skills, he is also engaged in developing his critical thinking strategies. In like manner, when a student is not involved in any of the two dimensions, it is expected that he is not also engaged in improving himself in the other dimension. The dimension where nursing students are least involved falls under critical thinking criteria. Although this dimension was identified to have a mean of 3.16 in problem 1, where students are actively involved in developing criteria indicators, this is the dimension where nursing students are least involved. This tells us that students might be more engaged in developing indicators or sub-dimensions of disposition skills, cognitive skills, and strategies when compared to criteria. When designing interventions in developing critical thinking among students, it can be inferred that focus can be given to criteria as this dimension is identified where nursing students have the lowest level of critical thinking. Other than these, it can be suggested that interventions can be designed to enhance disposition skills and improve their cognitive skills, critical thinking strategies, and critical thinking criteria. Also, enhancers and barriers can be considered in designing interventions found in problem 5. New approaches to student clinical tasks could be implemented as the student progresses through the curriculum to boost critical thinking skills. Case studies, conceptual maps, simulations, reflective writing, role-playing and problem-based learning (PBL), YouTube videos, and other teaching methods are examples of critical thinking skills resources for nurse educators. These strategies are found to be effective. These can be utilized aside from lectures and pure discussions. In a systematic review conducted by [42], it was found that PBL, one of the abovementioned possible interventions, is more effective in promoting critical thinking development among undergraduate nursing students than lectures. Other than this, it was suggested by [43] that clinical hours in nurse education can be decreased and replaced with simulations. Moreover, [44] identified that students’ attendance in simulation could increase their confidence, which is one of the indicators of critical thinking.

BSN students of CAR possess dimensions of critical thinking with different scores obtained. In terms of dimension where nursing students have the greatest involvement, developing disposition skills ranked the highest. It can be noted that students are most involved in improving themselves in being open-minded, inquisitive, and being fair. As earlier revealed, students are greatly actively involved in developing almost all indicators of disposition skills. Next to disposition skills is the dimension of cognitive skills. The inequality may suggest that nursing students have a higher level of critical thinking in terms of disposition skills than their cognitive skills. In like manner, students have a lower level of critical thinking in terms of cognitive skills than in their disposition skills. Further, students are more engaged in showcasing indicators or the sub-dimensions of disposition skills (open-mindedness, inquisitiveness, and fairness) than involving themselves in indicators or sub-dimensions of cognitive skills (analysis, interpretation, inference, explanation, evaluation, self-regulation, and analytical). The analysis tells us that there is a probability that nursing student does not equally showcase or engage themselves in being open-minded and analytical as an example. Compared to critical thinking strategies, the cognitive skills dimension appears to have no statistically significant difference. Nursing students, in other words, are equally engaged in these two dimensions of critical thinking. Meaning, when a student improves himself with his cognitive skills, he is also engaged in developing his critical thinking strategies. In like manner, when a student is not involved in any of the two dimensions, it is expected that he is not also engaged in improving himself in the other dimension. The dimension where nursing students are least involved falls under critical thinking criteria. Although this dimension was identified to have a mean of 3.16 in problem 1, where students are actively involved in developing criteria indicators, this is the dimension where nursing students are least involved. This tells us that students might be more engaged in developing indicators or sub-dimensions of disposition skills, cognitive skills, and strategies when compared to criteria. When designing interventions in developing critical thinking among students, it can be inferred that focus can be given to criteria as this dimension is identified where nursing students have the lowest level of critical thinking. Other than these, it can be suggested that interventions can be designed to enhance disposition skills and improve their cognitive skills, critical thinking strategies, and critical thinking criteria. Also, enhancers and barriers can be considered in designing interventions found in problem 5. New approaches to student clinical tasks could be implemented as the student progresses through the curriculum to boost critical thinking skills. Case studies, conceptual maps, simulations, reflective writing, role-playing and problem-based learning (PBL), YouTube videos, and other teaching methods are examples of critical thinking skills resources for nurse educators. These strategies are found to be effective. These can be utilized aside from lectures and pure discussions. In a systematic review conducted by [42], it was found that PBL, one of the abovementioned possible interventions, is more effective in promoting critical thinking development among undergraduate nursing students than lectures. Other than this, it was suggested by [43] that clinical hours in nurse education can be decreased and replaced with simulations. Moreover, [44] identified that students’ attendance in simulation could increase their confidence, which is one of the indicators of critical thinking. 4.3. Relationship Between Profile Variables of Nursing Students and Their Ratings in the Critical Thinking Dimensions

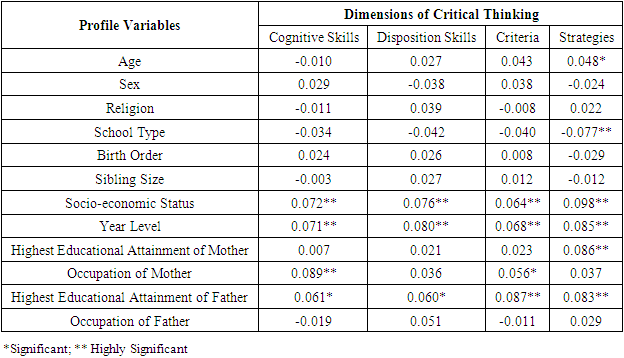

- Three of the profile variables of the students, namely socio-economic status, year level, and highest educational attainment of the father, were found to be statistically correlated with all dimensions of critical thinking.

|

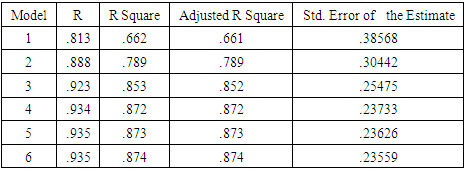

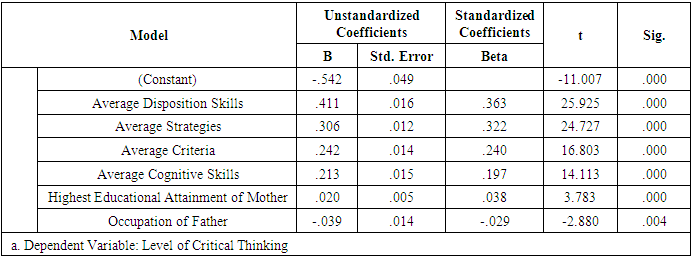

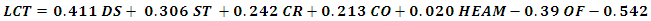

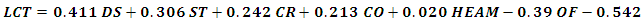

4.4. Linear Combination Nursing Students’ Profile Variables and Dimensions of Critical Thinking

- Sixteen (16) variables consisting of selected demographic profile and dimensions of researcher-made critical thinking questionnaire for nurses as potential predictors or explanators of the level of critical thinking among nursing students. The following table shows the models and its predictive power.

|

|

where LCT is nursing students’ level of critical thinking;DS is the average on nursing students’ disposition skills as one dimension of critical thinking;ST is the average on nursing students critical thinking strategies as of the dimensions of critical thinking;CR is the average on nursing students’ critical thinking criteria as another dimension of critical thinking;CO is the average on nursing students’ cognitive skills as one of the dimensions of critical thinking among nursing students;HEAM is the highest educational attainment of the mother using the following category: 0 (Did not attend school), 1 (Elementary Graduate), 2 (High School Graduate), 3 (Vocational/Diploma Certificate Holder), 4 (College Degree), 5 (Masters Degree), 6 (Doctorate Degree), 7 (Post-Doctorate Degree).OF is the occupation of the father where 1 (one) pertains to white-collar jobs while 2 (two) are blue-collar jobs, The model has the following characteristics:Nursing student’s level of critical thinking is higher when the score in any of the four dimensions of critical thinking: cognitive skills, disposition skills, criteria, and strategies are higher (this is true when comparing two students with the same highest educational attainments of their mothers and occupations of their fathers). In like manner, nursing students will obtain a lower level of critical thinking when the score in any of its dimensions is lower. The higher the educational attainment of mothers of nursing students, the higher the level of critical thinking a student may possess or be relatively more involved in developing critical thinking (this is true when comparing two students with the same rating in all dimensions of critical thinking skills). Likewise, the lower the highest educational attainment of the mother, the lower level of critical thinking a nursing student may obtain. The level of critical thinking of nursing students is higher when their father has a blue-collar job. Equivalently, the level of critical thinking of nursing students is relatively lower when their father has a white-collar job. The highest possible value of nursing students’ level of critical thinking using the model is 3.966, which can be categorized as greatly actively involved. On the other hand, the lowest rating that can be obtained using the model is -0.01. It can be observed in the highest and lowest rating that it ranges between -0.01 and 3.966, but it can be noted that the highest rating a nursing student can obtain is 4 and that the lowest possible level is 1. Thus, it is not meaningful when a nursing student obtains a rating lower than 1. It was mentioned earlier that the model could predict 87.40% only of the value calculated through the regression model. Surprisingly, it can be generalized based on the model's property that a nursing student can relatively obtain a higher level of critical thinking when their mother has higher educational attainment and when their father has a white-collar job. Based on the studies of [45,46,35], several predictors of critical thinking have been discovered, which are different from predictors of the level of critical thinking found in the present study. [45] found that caring behavior among Turkish nursing students predicts critical thinking. [46] conducted a study among nursing students in Saudi Arabia and found that emotional intelligence can predict critical thinking disposition. In addition, [35] conducted a regression analysis to determine the predictive variables for critical thinking. The results show that reading habits, father's educational level, university entrance examination grade, family socio-economic level, and mother's education level were the most significant predictors of the overall tendency to think critically. From the study's philosophical standpoint, it can be deduced that critical thinking is described by various variables arising from numerous settings or contexts, such as the study environment. Generally, the result is consistent with the pragmatic view of philosophy, especially on its ontological beliefs that the relationship among and between profile variables and critical thinking dimensions varies depending on the study environment. This pragmatic approach to philosophy is seen in the developed mathematical model in predicting the level of critical thinking of nursing students.

where LCT is nursing students’ level of critical thinking;DS is the average on nursing students’ disposition skills as one dimension of critical thinking;ST is the average on nursing students critical thinking strategies as of the dimensions of critical thinking;CR is the average on nursing students’ critical thinking criteria as another dimension of critical thinking;CO is the average on nursing students’ cognitive skills as one of the dimensions of critical thinking among nursing students;HEAM is the highest educational attainment of the mother using the following category: 0 (Did not attend school), 1 (Elementary Graduate), 2 (High School Graduate), 3 (Vocational/Diploma Certificate Holder), 4 (College Degree), 5 (Masters Degree), 6 (Doctorate Degree), 7 (Post-Doctorate Degree).OF is the occupation of the father where 1 (one) pertains to white-collar jobs while 2 (two) are blue-collar jobs, The model has the following characteristics:Nursing student’s level of critical thinking is higher when the score in any of the four dimensions of critical thinking: cognitive skills, disposition skills, criteria, and strategies are higher (this is true when comparing two students with the same highest educational attainments of their mothers and occupations of their fathers). In like manner, nursing students will obtain a lower level of critical thinking when the score in any of its dimensions is lower. The higher the educational attainment of mothers of nursing students, the higher the level of critical thinking a student may possess or be relatively more involved in developing critical thinking (this is true when comparing two students with the same rating in all dimensions of critical thinking skills). Likewise, the lower the highest educational attainment of the mother, the lower level of critical thinking a nursing student may obtain. The level of critical thinking of nursing students is higher when their father has a blue-collar job. Equivalently, the level of critical thinking of nursing students is relatively lower when their father has a white-collar job. The highest possible value of nursing students’ level of critical thinking using the model is 3.966, which can be categorized as greatly actively involved. On the other hand, the lowest rating that can be obtained using the model is -0.01. It can be observed in the highest and lowest rating that it ranges between -0.01 and 3.966, but it can be noted that the highest rating a nursing student can obtain is 4 and that the lowest possible level is 1. Thus, it is not meaningful when a nursing student obtains a rating lower than 1. It was mentioned earlier that the model could predict 87.40% only of the value calculated through the regression model. Surprisingly, it can be generalized based on the model's property that a nursing student can relatively obtain a higher level of critical thinking when their mother has higher educational attainment and when their father has a white-collar job. Based on the studies of [45,46,35], several predictors of critical thinking have been discovered, which are different from predictors of the level of critical thinking found in the present study. [45] found that caring behavior among Turkish nursing students predicts critical thinking. [46] conducted a study among nursing students in Saudi Arabia and found that emotional intelligence can predict critical thinking disposition. In addition, [35] conducted a regression analysis to determine the predictive variables for critical thinking. The results show that reading habits, father's educational level, university entrance examination grade, family socio-economic level, and mother's education level were the most significant predictors of the overall tendency to think critically. From the study's philosophical standpoint, it can be deduced that critical thinking is described by various variables arising from numerous settings or contexts, such as the study environment. Generally, the result is consistent with the pragmatic view of philosophy, especially on its ontological beliefs that the relationship among and between profile variables and critical thinking dimensions varies depending on the study environment. This pragmatic approach to philosophy is seen in the developed mathematical model in predicting the level of critical thinking of nursing students. 4.5. Enhancers and Barriers

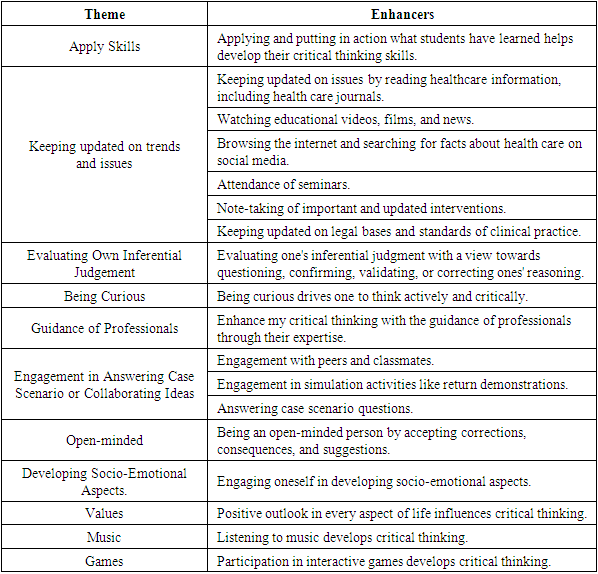

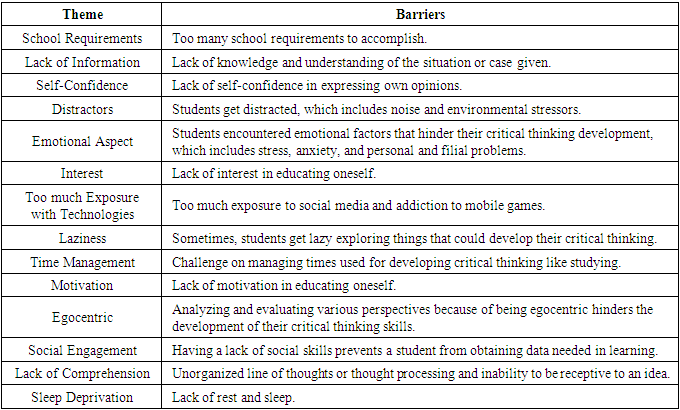

- Eleven themes depending on their nature, surfaced as enhancers of critical thinking, that includes (a) applying skills, (b) keeping updated on trends and issues, (c) evaluating own inferential judgment, (d) being curious, (e) through professional guidance, (f) engagement in answering case scenario or in collaborating ideas, (g) being open-minded, (h) developing socio-emotional aspects, (i) improving values, (j) listening to music, and (k) playing games.

|

|

5. Limitations of the Study

- The researchers identified enhancers and barriers in developing critical thinking but did not offer suggestions on how to develop enhancers nor give solutions to address or overcome barriers.

6. Conclusions

- A reliable instrument was designed to measure the level of critical thinking among Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) students in the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR). In the light of the salient results of this study, the following conclusions were drawn:1. BSN students actively develop critical thinking in four dimensions: cognitive skills, disposition skills, strategies, and criteria.2. BSN students should focus on improving cognitive skills, strategies, and criteria to enhance critical thinking.3. Some profile variables are statistically correlated with dimensions of critical thinking (Highest Educational Attainment of Father, Occupation of Mother, Highest Educational Attainment of Mother, Year Level, Socio-economic Status, school type, and age) but show a very weak correlation.4. The level of critical thinking (LCT) can be predicted using the constructed mathematical model with variables disposition skills (DS), cognitive skills (CS), strategies (ST), criteria (C), highest educational attainment of mother (HEAM), and occupation of father (OF). The model can give us about 87% true values of the predicted values.

Students need to focus on developing all dimensions of critical thinking, especially disposition skills. Fathers with white-collar jobs might have obtained more advanced knowledge that helped students develop their critical thinking.5. There are factors that hinder and enhance the development of nursing students’ critical thinking that should be avoided and observed. Programs need to be crafted to increase and address factors that hinder their critical thinking development.

Students need to focus on developing all dimensions of critical thinking, especially disposition skills. Fathers with white-collar jobs might have obtained more advanced knowledge that helped students develop their critical thinking.5. There are factors that hinder and enhance the development of nursing students’ critical thinking that should be avoided and observed. Programs need to be crafted to increase and address factors that hinder their critical thinking development.7. Recommendations

- In view of the findings and conclusions brought about by this study, the following are recommended: School administrators of schools of nursing should design interventions in improving the critical thinking of nursing students especially on the dimensions where students found to be at lowest level of critical thinking or least involved. In developing interventions in improving critical thinking, it can be considered to focus on critical thinking criteria and cognitive skills as it were found to be the dimension where nursing students are least involved. Although only occupation of the father and highest educational attainment of the mother can statistically predict the level of critical thinking among profile variables, learners are encouraged to develop their critical thinking utilizing identified enhancers and attend seminars on how to avoid or reduce the risk of encountering barriers in developing individual’s critical thinking.Parental involvement is important for students’ scholastic and socio-emotional development, as well as their critical thinking. However, not all parents can favorably affect their children’s critical thinking development, particularly when the parents, such as the mother, have a lower educational level. The same is true for parents with white-collar jobs who may have less time to join their children in developing CT due to their workloads. Students can seek assistance from older family members like siblings, community experts, and school stakeholders to help them develop critical thinking skills. Educators and scholars may utilize the mathematical model in predicting and gathering information on nursing students’ level of critical thinking. This can help in formulating programs for nursing towards the development of their critical thinking.School administrators and nursing faculty members are encouraged to use the developed instrument called Critical Thinking Instrument for Nursing (CTIN) in assessing the level of critical thinking among their nursing students in order to design programs for students towards development of students’ critical thinking. Scholars may also adopt the questionnaire in measuring critical thinking – including enhancers and barriers identified by nursing students. Accomplishing such studies will serve as basis for the commission in elevating the competence of nurses.Future researchers may conduct studies on critical thinking using the instrument in a different context to explain further the ontology of pragmatism and verify if critical thinking is different from another context. They may utilize different methodology such as phenomenology or case study in understanding enhancers and barriers of critical thinking. The study can be replicated utilizing random sampling technique in identifying respondents of the study. Aside from the profile variables included in the study, future researchers can empirically explore other variables that can predict the level of critical thinking to further determine whether excluded variables in regression model can adequately predict the level of critical thinking as suppressor variables.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The researchers would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the people and institutions who contributed significantly to the research process. Their assistance is of great importance to the success of this project.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML