-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2023; 13(1): 1-11

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20231301.01

Received: Mar. 29, 2023; Accepted: Apr. 14, 2023; Published: Apr. 23, 2023

Resilience of Women Living with Breast Cancer: Study of Autobiographical Discourse of Women Living with Breast Cancer followed at the Joliot Curie Institute, Dakar, Senegal

Dieynaba Fall1, CheikhIbrahima Niang1, Mory Diallo1, Ahmadou Dem2

1Faculty of Sciences and Technologies/Institute of Environmental Sciences, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal

2Joliot Curie, Institute, Dakar, Senegal

Correspondence to: Dieynaba Fall, Faculty of Sciences and Technologies/Institute of Environmental Sciences, Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar, Senegal.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background. Breast cancer is the most diagnosed cancer in the world with 2 261 419 cases. In sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Senegal, breast cancer ranks second with an estimated 1,817 new cases (16%) and 956 (11%) deaths. The diagnosis of breast cancer puts women in great emotional and financial distress. Resilience is the ability to put in place responses to continue living after a shock. The aim of this study is to see how women living with breast cancer build their resilience. Methods: We conducted an in-depth case study. In the approach, we chose a qualitative methodology with the use of semi-structured interviews, direct observation, and documentation for data collection. Results: we have representations and attitudes (redefinition of the disease, change of representations, positive denial) that lead to the adoption of resilient practices and behaviours (management of emotions and stress, organization to ensure financial expenses, family organization, maintenance of professional activities) among women living with breast cancer. Conclusion: In the course of the study, we found that women progressively constructed coping and resilience strategies in response to their situation. Nevertheless, health policies and decision-makers need to strengthen this resilience in order to improve the quality of life and increase survival of patients.

Keywords: Women living with breast cancer, Resilience, Vulnerability, Distress, Survival, Institut Joliot Curie

Cite this paper: Dieynaba Fall, CheikhIbrahima Niang, Mory Diallo, Ahmadou Dem, Resilience of Women Living with Breast Cancer: Study of Autobiographical Discourse of Women Living with Breast Cancer followed at the Joliot Curie Institute, Dakar, Senegal, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 13 No. 1, 2023, pp. 1-11. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20231301.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Breast cancer is the most diagnosed cancer in the world with 2 261 419 cases [1]. In sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Senegal, breast cancer ranks second with an estimated 1,817 new cases (16%) and 956 (11%) deaths [2]. In contrast to developed countries, in Africa, breast cancer occurs most frequently in women of reproductive age [3,4,5,6]. Breast cancer has the highest life expectancy of all cancers if detected early and managed appropriately. Survival rates for breast cancer at least five years after diagnosis vary considerably, reaching over 90% in high-income countries, compared to only 66% and 40% in India and South Africa, respectively [7]. These earlier studies show that delayed diagnosis gives patients a poor chance of survival. In high-income countries, early detection and prompt treatment have been shown to be effective. A recent study in five sub-Saharan African countries estimated that 28-37% of breast cancer deaths in these countries could be prevented by early diagnosis at the onset of symptoms and adequate treatment [8]. However, in Senegal, the majority of patients were locally advanced in 80.7% of cases [9]. In addition, access to treatment and its high cost, as well as the side effects of treatment, are other factors of vulnerability for the patient. In poor settings, the costs of NCD-related health care are rapidly depletingles household resources. Breast cancer not only leads to economic impoverishment, but also has negatives psychosocials and health implications. According to several authors, the announcement of cancer causes shock, followed by distress, fear, changes in social relationships [10,11], but also anxiety and deterioration of physical health. Depression and stress have been also reported [12,13]. Resilience is cited as being able to improve the quality of life of patients [14]. Resilience can be defined as a process of mobilising resources to maintain well-being [15]. For [16] resilience is an outcome pattern following a PTE (Potentially Traumatic Events) characterized by a stable trajectory of healthy psychological and physical functioning. A meta-analystic studies have revelead that resilience is associated with multiple clinical, socio-demographic, social and physiological variables [17,18]. In addition psychological factors being the main contributors to the development of resilience. Some protective factors have been identified, such as social support, several dimensions of quality of life (QOL) and coping strategies [17]. In Senegal, We lack scientific data on the responses of women living with breast cancer to the context. Resilience for this study is the response of women living with breast cancer to continue their lives. This article will analyse the economic, emotional or affective collapse of patients following a breast cancer diagnosis and how they build resilience in this context.

2. Méthodes

- This article is based on our thesis work on the living conditions of women with breast cancer. For this purpose, we conducted an in-depth case study. The case study is an empirical research strategy that allows contemporary phenomena to be placed in their real context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not obvious [19]. It allows the researcher to explore simple individuals or organisations through complex interventions, relationships, communities or programmes [20]. In other words, the case study allows us to know the conditions of evolution of a phenomenon in a given context. Thus, to find out how women with breast cancer cope with the financial, psychosocial and health implications and the strategies they put in place to overcome barriers and challenges, we chose to conduct an in-depth case study. Patients were selected at the hospital and followed from 2019 to 2022. We made regular home visits to put ourselves in the patient's shoes and experience geographical access to care, family space, management of daily household tasks and telephone conversations. We accompanied them, which allowed us to build trusting relationships with women and their families. These different stages allowed us to experience the life trajectory of the patients and to share their emotions while keeping the requirements of the research. Having several cases allowed us, on the one hand, to have a diversified source of information which reinforces the reliability of the information through triangulation. The other hand, it allowed us to have the common points of the patients and their particularities. To collect the data, the qualitative method of semi-structured interviews allowed us to collect the patients' accounts in the form of autobiography. In his attempt at a definition, [21] defines autobiography as "a retrospective prose account that a real person makes of his own existence, when he focuses on his individual life, in particular on the history of his personality". We used autobiography in the case of breast cancer to find out how the patient sees herself, what image she has of cancer and her life, her living conditions, how she organises herself to mobilise the economic, social and cognitive resources to continue living. In addition, we carried out direct observation of their living environment, their social environment and their relationship with the health staff.

2.1. Recruitment Process

- This study was conducted in accordance of ethic rules and pratices. The study received approval from the Cheikh Anta Diop University and the agreement of the research committee of the Institut Joliot Curie. A presentation of the project was made to the patients or the person in order to obtain their agreement. Codes were assigned to each participant to ensure confidentiality during the interviews and in the transcripts. Participants could stop the interview at any time. The protection of confidentiality and the respect of personal data were strictly adhered to. A preamble (associated with this article) introducing the project was also presented to each participant. The inclusion criteria for patients were to be Senegalese, at least 18 years old and at most 80 years old. Traditional healers had to be in contact with the patients. The caregivers had to be specialists in breast cancer or all cancer sites, have completed their specialisation or be in training, and work at the Joliot Curie Institute.

2.2. Interview Process

- Recruitment was carried out at the Institut Curie at the time of the consultation or in the chemotherapy room with the help of the nurses who were familiar with the patient's file. We made two to three visits to the patients' homes. Five telephone interviews were carried out because the context of covid-19 did not allow us to visit the patients. The interviews lasted between 30 minutes and 1 hour. The in-depth interviews were conducted using an interview guide prepared for each target group based on the observations and informal discussions during the exploratory phase. Overall, the majority of the interviews took place at the patient's home or hostel and three (03) at the hospital because the patient lives in the region and had to return there after the chemotherapy session. The interviews were recorded or noted if recording was refused. They included 17 patients and their escorts, family members, medical oncologists (4), two traditional healers and 2 LISCA members. Informal interviews were also conducted with the patients. The guide was improved as the interviews progressed in order to deepen certain questions or to add others that had not been taken into account at the start. Interviews with patients and caregivers covered the following issues: Income-generating activities, how they pay for treatment, the patient's role in the family, money spent so far, side effects and their management, people involved in the treatment, and to what extent the reactions to the announcement of the disease, feelings, fears, support, reaction of the family or close people, physical changes, perceptions and representations, and behaviour. The interviews with the staff covered: General information about breast cancer, clinical signs, diagnosis, confirmatory tests, treatment and problems encountered. The interviews with the traditional healers focused on: The practitioner's activities, knowledge of cancers and breast cancer, the profile of cancer patients, reasons for consultation, breast cancer treatment and its course, cost of treatment and its duration.

2.3. Analysis

- The interview was conducted in Wolof (the most popular local language) and transcribed into French, then organised by target and date. After transcription, we carried out a content analysis of the interviews. The data was organised and grouped around evocative themes. After this categorisation, the extracts were grouped under the corresponding theme until the information was saturated. The verbatim statements were noted, and then the constructions and analyses surrounding them were studied. Content analysis was used to generate the situations of collapse after the cancer announcement, the processes and determinants of resilience. This analysis begins with a description of the data, followed by explanations of the factors, social constructs, interpretations and context of the demand for care before discussing the results.

3. Results

- At the end of this work, the following results will be presented. The different situations of collapse following the announcement of breast cancer and the strategies to cope with the challenges by women living with breast cancer.

3.1. Socio-demographic Characteristics of the Sample

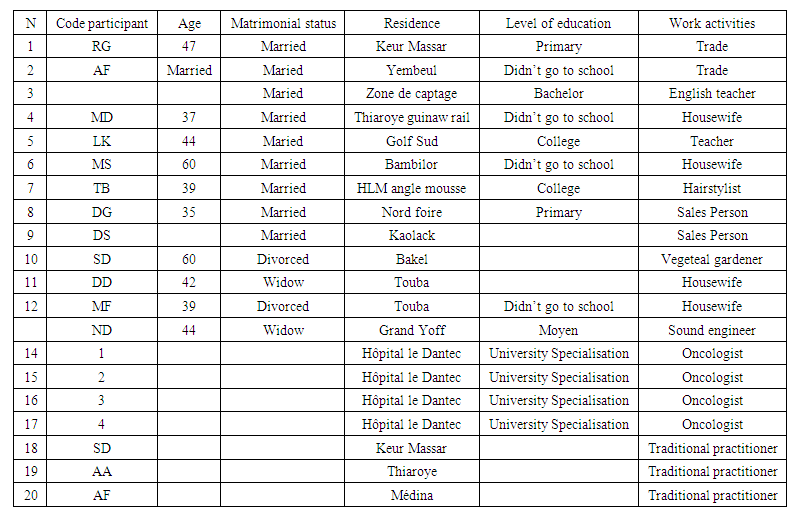

- The patients' ages ranged from 23 to 60 years (see Appendix).

| Table 1. Participants in semi-structured interviews |

3.2. The Collapse of Economic Power

- The aim of this section is to analyse the economic impact of cancer treatment. It shows how women living with breast cancer organise themselves to cope with the costs of treatment. As described above, the majority of the patients we met did not have a fixed income or health insurance. Coming from a poor family barely able to meet their daily needs, the additional burden of cancer treatment further pushes them into economic insecurity. From the first symptoms of the disease to its confirmation and treatment, a woman with cancer has to deal with a major drain on her savings. In the first instance, a lot of money is spent on researching the disease. After the consultation, various tests are prescribed. Most often, this involves a mammogram and a biopsy. But in some situations this is not enough to confirm the disease. In fact, one patient had to undergo two biopsies, followed by an ultrasound-guided biopsy for diagnosis. She claims to have spent a large amount of money to make the diagnosis, estimated at 329 $ or more. On the other hand, one woman, DM (44 old), gave an insight into her experience and perception of the cost of diagnosis: « I spent 41 $ to do a biopsy, which I did three times, and then as the result was not clear to confirm the diagnosis, I did another ultrasound guided biopsy to confirm the cancer ».This testimony describes on the one hand the high cost of the diagnosis that the patient perceives as high and for the other patient, she describes the difficulty of making an accurate diagnosis and the cost that she has to unfairly bear. For those who are not from Dakar, after the results, they are referred to Curie Institute because of the lack of specialists in their home region. Then, after confirmation of the cancer, a prechemotherapy, a Extensional assessment (depending on the case) and a CT scan are requested.The cost of chemotherapy is estimated by specialists to be between 2469 $ and 3292 $. There is also the surgical intervention which consists of the total or partial removal of the breast and all the lymph nodes before continuing or not chemotherapy. Radiotherapy was prescribed for some patients. Another patient had a relapse, the other breast had started to develop cancer, and she had to spend an extra 2469 $ for treatment. Her carer seems distraught about the situation: "Now she is lying down, I have nothing left and I have no one to help me".The treatment costs are therefore exorbitant, not to mention the money for transport and food. To alleviate the costs, one patient explains: « I usually come with my elder son but now I come alone because I can't afford his transport and breakfast for both of us ».Only two of the patients we met have health insurance and represent those on a fixed income. Those without health insurance did not have the money to make the diagnosis, let alone the cost of treatment, which varies between 2 and 3 million FCFA. This is a sum that women have to raise in order to receive prompt and effective treatment. Moreover, the arrival of breast cancer disrupts the life of the woman and her family, which is not without emotional consequences.

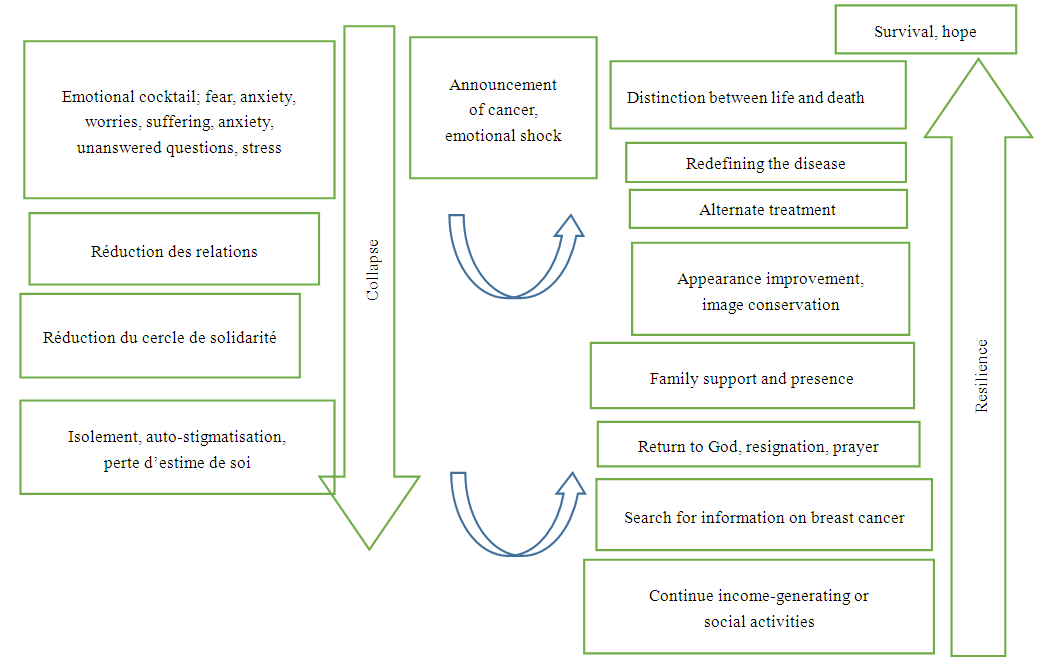

3.3. Emotional and Psychosocial Collapse

- The announcement of cancer is followed by an emotional shock, first for the woman and then for her relatives. For some, it is a surprise; Others have had time to gradually prepare themselves for the idea during the search of kind of disease. But the idea of having cancer and living with it is a burden, an emotional shock for patients and their families. Each patient reacts to the news in her own way. But they all feel an emotional mix of fear, uncertainty, dark thoughts of death, anxiety and despair. One woman said: « When I was told I had the disease I was shocked, I don't know if I could stand up, then I sat down and stood up and waited impatiently for the doctor. I wondered where I got this disease, what would happen to my children? »Another, on the other hand, expected to develop cancer in her life because her mother and older sister died of ovarian cancer; she had her suspicions but was desperate "diakhlé" (in the local Wolof language), when she got the confirmation. Only two patients confided their illness to their family and friends. The others wanted to keep it a secret or shared it with a limited number of close friends. Some kept everything to themselves so as not to arouse suspicion. On this point, one woman said: « I run a tontine in the neighbourhood, but since the illness, I no longer attend our meetings, although I still pay my dues. They still know that I am ill, but not what I am suffering from ».Others do not want to tell certain family members in order to spare them an emotional shock. This attitude of some patients helps to avoid other collapsing situations such as the reduction of social solidarity. Indeed, the patients feel the circle of solidarity shrinking all the more. Some, at first, benefited from the assistance but has been reduced over time this situation mainly affects people who do not live in Dakar. They are hosted by relatives during their stay in Dakar. But this hospitality disappears over time. The reasons given were: the host family moved, there was no one to assist the patient, and there was no money to cover the patient's needs during her stay. G.F., a carer, describes all the difficulties he faces: « This lady was the wife of my brother, who died a few weeks ago from an illness. I took over to help her with her treatment. But at the moment I can no longer accommodate her at my home. At home we leave early in the morning and only return in the evening. She might be alone during the day and that's not safe. So, after the chemo, she will return to Touba ». Transport prices also vary according to the time of year. This may not be easy depending on the context. Some patients fall back on their mother's family to better support her. X C, a patient, says:« I used to live in Mali, and as I often fell ill and my husband could not afford to take me for consultations, I came back to Senegal and that's when I was told that I had the disease, and since then I have stayed to be treated. My brother takes care of all the treatments ».Seeing the social circle shrink can awaken a different sense of self. The Women also experience a loss of self-esteem leading to self-isolation. One patient has turned in on herself because she thinks she is the victim of a curse. Her life is made up, according to her, of many sufferings. She describes this suffering as follows: « My life is worthless, I live from sorrow to sorrow, I have never known happiness. I was married twice but it never lasted, after my divorce with my husband he took custody of the children, the second marriage was also the same, my husband had epileptic seizures and beat me... Since I have been ill, he has not even come to see me… ».This loss of self-esteem leads to depression caused by her inability to fully play her role at home due to fatigue, side effects of treatment, and interpersonal loss. She continues: « What hurts me the most is that I can't even wash my children's clothes anymore ».In the face of this emotional collapse, they try to pick themselves up and face the challenges. However, as a result of the shock and the emotional and social effects, patients develop strategies to survive.

3.4. Determinants of Resilience

- Resilience for these women is the way in which they have overcome the distress caused by cancer. We will see in their situation the processes, the mechanisms they put in place to meet the challenges to continue living. This resilience is characterised by the following elements.

3.4.1. Building Cognitive Resilience

- In response to the stress and emotional decline that follows the diagnosis of cancer, patients develop the mental strength and self-estim needed to get back on their feet. The resilience strategies they develop include the distinction between illness and death. Indeed, the majority of the women said that being ill is not synonymous with death, one can die without being ill. Some even said that close family members had died suddenly, even though they seemed fine the day before. They also try to change the label of the disease, treating cancer as any other disease. They change their relationship with cancer so that it has less weight:« I now see cancer as malaria; I see it as having malaria and I do what I have to do to be cured and it is possible to be cured ».This attitude gives them hope. They also place the disease in the religious register, considering it as a divine test "nattu", and the only thing to do is to accept it, get closer to God, pray and follow the treatment. One of the patients (MS, 60) said:« I bring everyone to Him because He is not afraid of anything, no one can postpone the time of death ».Many patients reported seeking advice from a religious guide. The religious guide is most often consulted to interpret dreams that have come back more than once. Some patients reported having recurring nightmares and that talking to a specialist about how to behave, pray and give alms helped them to deal with their fears and anxieties. They also want to preserve their image by taking care of their physical appearance and trying to keep their pre-disease appearance. All the patients lost their Some of them, although well aware of the importance of the lost organ, play down the loss by joking about it. Some of them, even though they are well aware of the importance of the lost organ, play down the loss by joking. For example, one of them says:« After At my operation, I asked my family when someone loses an eye or a hand, they call it 'an eye', or 'a hand', and for someone who only has one breast, they call it 'a breast'... which makes everyone laugh. »The social support is essential to manage the fear and allows the patient to keep hope and to evacuate the uncertainty. The support of family and friends, their exchanges, discussions and laughter allow the patient to better evacuate her anxiety and stress. In addition, the stress caused by the lack of communication is managed by information obtained from the media. Indeed, searching for information on the internet about the disease and treatment is also a way of coping with the uncertainties and unanswered questions that increase the stress of some patients. This information helps to clarify the situation. RG (48 old) tells us how the internet helped her to relieve her stress: « I heard many things about chemotherapy. I am doing research on YouTube and that's where I got information about the disease and the treatment, which reduced the dose of stress ».This increased knowledge of cancer, as well as mental and emotional strength, led to positive behaviours.

3.4.2. Adoption of Practices and Behaviours that Promote Resilience

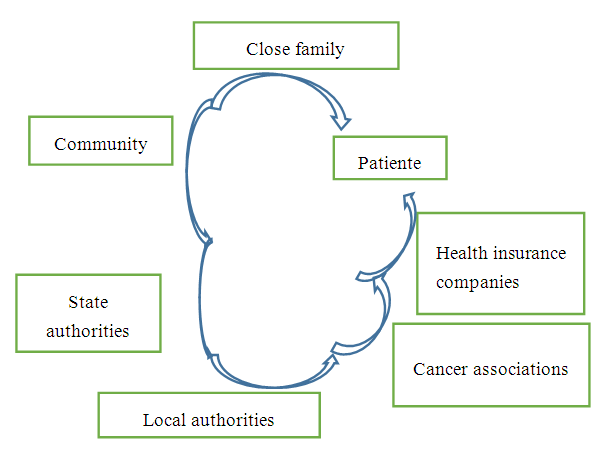

- Practices and behaviours are at the individual level, but also at the family and community level. Indeed, faced with the financial needs of treatment, patients with the help of their families have undertaken actions such as: the sale of jewellery or valuable objects at a derisory price far from the value of the "wanter" object. In this aspect, one RG (48 old) declared: « One day I sold my gold chain. I had bought it for 822 $ and I sold it for 444 $ to please myself; my daughter cried when she found out, she said to me: mama, you sold all your jewellery. I sold all my gold jewellery for these evaluation cases because I am ashamed to go and ask for help. »They can also take advantage of free consultations. Indeed, two patients waited for the world day dedicated to the fight against breast cancer, "Pink October", to be able to benefit from free consultation and a reduction in the cost of the mammography to 12,34 $ instead of 41 $. Another patient, who lives outside Dakar, waited for the free consultation sessions to see the doctor. She was then referred to Dakar. Patients may also receive support from family members or friends. This support often comes at the time of diagnosis, but also during the course of treatment. This support can also come from a close friend or parents. One patient explained her situation as follows: « I have no one to help me, my children are young. My eldest son passed his baccalaureate last year and his first scholarship was used to treat my illness. Sometimes a network of financial solidarity develops at the community level to support a patient, as the following example shows. The carer (JL 64 old) testified:« The association she [the patient] belonged to before she left made a collection in the neighbourhood, on the markets. We were able to collect a large amount of money ».Another carer FG (25 old) said:« before the chemotherapy session, I contacted my friends living abroad via social networks and they shared the information with their friends and family: this allowed us to pay for the chemotherapy ».Patients can also rely on social media. One woman reported that she sought financial support through a television show. Another woman made a video and posted it on YouTube and Facebook. She explains: « It was a teacher friend who helped me make a video and put it on YouTube with my number, so I got a lot of money and I got a lot of people to visit me, which was very comforting ».National or local authorities and patient support groups can be of great help to patients. For example, two patients received support from their political party and one from the local community. Five other patients received support from associations such as Lisca (Ligue Sénégalaise de Lutte contre le Cancer), for diagnosis and medical care. However, the economic power offered by these different strategies developed by the patient gradually fades over time as the treatment becomes more permanent. Indeed, with repeated chemotherapy protocols, surgery, relapses and radiotherapy, and metastases, the use of economic support decreases as the community solidarity network and social networks run out of steam over time. Medical aid organisations often do not have enough drugs or money and are not able to pay for examinations. The patient is therefore unable to take care of herself, which leads to feelings of anxiety, uncertainty and stress. On this point, one carer (DF 35 old) said:« We used to have lots of people offering to help us, but now we don't see anyone and the doctor tells us that the other breast has developed cancer and we have nothing ».What the woman said eloquently shows the difficulties she is going through:« My husband used to buy the medicines but since his death I have been living in a state of turmoil, because I have to pay a prescription of 100,000 francs a month. I have finished chemotherapy, the breast has been removed and it is healing well. But recently the doctor told me that the disease has moved to my spine, I am in a lot of pain. I have to continue with radiotherapy and this is where my husband's absence is felt because he was my only support" (patient ND, 47) ».For those who have medical insurance they also face problems because they have to find money to pay for prescriptions or medicines. The amount spent may be reimbursed by the insurance, but often with a long delay. One of the two women with insurance reported difficulties in getting tests or paying for prescriptions as she does not necessarily have the money to pay for them. She is forced to seek help to recover the money owed to her by the insurance company. Figure 1 below describes the different parties involved in the patient's care.

| Figure 1. The different sources of funding for breast cancer treatment among the patients followed |

| Figure 2. Diagram of patients' emotional collapse and resilience strategies |

4. Discussion

- This article focuses on the resilience of women living with breast cancer. It shows how, in a context of economic insecurity and emotional collapse, women manage to overcome the obstacles and continue to live. They have little financial autonomy and a low level of education that does not facilitate access to good information. All this in a health system whose organisation and functioning do not meet the needs of the patients, putting them to living conditions that risk worsening their health. However, despite their situation, they have developed representations, attitudes and behaviours that promote resilience. In a systematic review, [22] concluded that 70% of patients perceive breast cancer as a financial burden. In Senegal, the direct medical cost of maximum treatment is. $10,662.97 and the cost of minimum treatment is $495.15, giving an average cost of $3,713.45 [23]. These results corroborate our findings on the economic burden of cancer. In a study in Vietnam, 34% of households became poorer at because of cancer treatment. According to [24] financial distress is a source of depression and negative impact on patients' well-being.This financial burden of breast cancer poses more problems for patients and their families who do not have financial support. However, since October 1, 2019, the State of Senegal has introduced free chemotherapy for breast and cervical cancer patients and this is a breath of fresh air for patients. On coping strategies, funding for treatment came from the following sources: savings funded 80% of breast cancer treatment, 10% increased credit card debt, 7% was borrowed from friends or family and 5% was debt to the hospital. 25% of women experienced a deterioration in their financial situation due to cancer [25]. This study is consistent with our findings. Women with low incomes are more affected by economic decline than those with stable incomes. This may be due to the fact that women with a professional status have care while those in the informal sector do not. For example in the [26] study found that levels of psychological resilience were significantly related to higher levels of quality of life in Swedish women with newly diagnosed breast cancer.Living with cancer is a struggle on many fronts. Authors such as [27]; [28] have reported on depression in patients. In South Africa [29] linked stress and depression states to body change and social support as significant predictors of psychological distress. Qualitative data showing that patients show symptoms of depression and anxiety to different stages of the process. Some showed a lack of confidence in the treatment they were receiving and a loss of self-esteem. Others were afraid and very anxious the day before the hospital appointment. This anxiety was mainly due to fear of chemotherapy and its side effects. In a study by [30], 64.4% of patients were afraid of the side effects of the treatment. But studies have shown that these stress and anxiety states disappear some time afterwards, [31,32,33,34]. This ability to return to a stable situation after the shock is called resilience. Burgess et al, 2005 found that in the first year after diagnosis, almost 50% of women with early breast cancer suffered from depression, anxiety or both, 25% in years two, three and four and 15% in year five. So [35], tried to understand the factors that enabled this resilience. So they examined the relationship between lifetime stress exposure before cancer diagnosis and psychological functioning after diagnosis in 122 breast cancer survivors. The data showed that moderate exposure to stress was associated with indicators of psychological resilience in the survivors. One of the key insights here is that exposure to stress is a means of coping with stress. In times of emotional distress, family support was an important element in boosting morale and enabling patients to cope. This assertion can be found in [36] study and [37]. [38] Kugbey et al, 2019 states that strong social support is associated with high quality of life. In our study, the majority of women are not menopausal. They have a high risk of quality of life. The quality of life of women living with breast cancer is lower than that of undeclared women living with breast cancer [39,40]. And high anxiety is associated with low quality of life [39,41]. Some protective factors have been identified, such as social support, several quality dimensions (QOL) and coping strategies [17,42,43]. Social support is seen as a positive action that can help patients overcome negative emotions. Social support is essential for building resilience and improving quality of life in Chinese breast cancer patients [44]. However [45] found that social support is consistently associated with a range of positive, but also negative outcomes, including relative risk of cancer mortality. This perception of social support is also important in that patients choose with whom to share information about the disease. This is primarily due to society's perception of the disease, and patients fear being stigmatised. Secondly, they also do not want people to feel sorry for them; they want to keep their dignity. The decrease in social support felt by some patients may be due to the fact that the disease lasts for a long time and over time the support system becomes exhausted. [17,18], state that resilience was associated with multiple clinical, socio-demographic, social, psychological and physiological variables. Psychological factors are the main contributors to the development of resilience. [46] state that women who adopted coping measures such as acceptance of the disease and religion had a better quality of life than those who did not have these coping measures. Moreover, spirituality is the most cited coping measure among cancer patients [47,48]. Similarly, [49,50,40] mentioned the importance of spirituality to improve health. These findings are consistent with the measures of resilience found in patients. However, [51] states that some patients do not want to receive social support because they see it as detrimental. It damages their self-esteem and mobilising support becomes a source of distress for them. [52], say that fatalism associated with a trivialisation of the diagnosis and acceptance of whatever the prognosis is, are sign of a lack of control in the patient. This results in attitudes of passive acceptance or resignation. The lack of information about breast cancer and its treatment is a source of distress for patients, as shown in the study by [53]. This explains the behaviour of some patients who seek alternatives to this lack of information on YouTube to reduce the stress of the unknown. This lack of access to information can be justified by the low level of education of women. Indeed, the majority of the women had not gone beyond primary school and only one woman had a higher education degree. Another measure of resilience is the change in the relationship with the disease. Because of their experiences, the information they have obtained and the possibility of a cure that exists, the women change the label of the disease. They see it as a disease that can be cured. People often perceive their illness as surmountable [54]. And this strategy is justified by the analysis of [55] who points out that the change in relationship from a threatening situation to a non-threatening one suppresses the thoughts that fuel stress. This explains the distinction between illness and death, the reinterpretation of illness and the maintenance of the appearance and image of the sick person. We did not find any studies in the literature on the perception of dreams and their interpretation in cancer patients. But in African culture, Senegalese in particular, there are many interpretations. In this study, patients see dreams as information about the future, about the unknown, as a warning about future events. This is important information that they need to decipher. These results are in contradiction with those of [54] who stated that many women thought that traditional healers were either frauds or unable to cure breast cancer.

5. Conclusions

- The journey of women with breast cancer is fraught with shocks that cause economic, emotional and physical collapse. Patients adopt resilience strategies to continue their treatment and maintain their health. Several actors are involved in the patient's care. To strengthen the resilience of women living with cancer, it is necessary to improve the living conditions of patients, a primary prevention policy is needed to encourage women to undergo early detection. But also, to find mechanisms of health coverage for vulnerable people, to strengthen the health system so that it responds to the needs of cancer patients, including psychosocial support for those who need it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- At the end of this article, we would like to thank Mr. Kisito Yang Mbengue, the staff of the Institut Joliot Curie, and all the women who participated in the study.

Disclosure

- The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML