-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2021; 11(3): 56-61

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20211103.02

Received: Jul. 31, 2021; Accepted: Aug. 12, 2021; Published: Aug. 25, 2021

Social Factors Associated with the Uptake of Screening Services for Early Detection of Cancer in Masinga Sub-County, Machakos County, Kenya

Bornventure Paul Omolo1, Sherry Oluchina2, Serah Kaggia3

1School of Nursing, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Machakos County, Kenya

2School of Nursing, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Kiambu County, Kenya

3School of Medicine, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Kiambu County, Kenya

Correspondence to: Bornventure Paul Omolo, School of Nursing, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Machakos County, Kenya.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

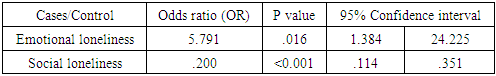

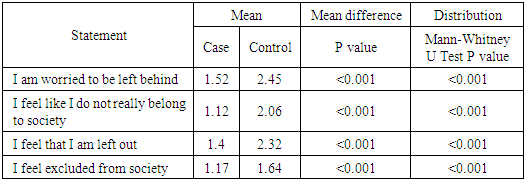

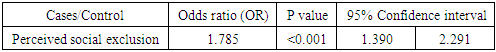

Social factors such as socioeconomic status are known to increase the risk of some cancers. Therefore, this study aimed at examining social factors associated with the uptake of cancer screening services in Masinga sub-county, Machakos county, Kenya. Study design used was case-control with systematic sampling method; quantitative data was collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire and analyzed using SPSS version 26.0. Chi square, Odds Ratios and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to determine significance of the association between outcome and independent variables. The data was presented using tables and narratives. Level of significance used was 5% (Confidence level of 95%). Focus group discussion guide was also used in enriching qualitative data. Data was gathered from a sample size of 42 cases (screened) and 116 controls (never been screened). Social variables assessed were social network and social exclusion. Qualitative data were collected from nine focus group discussions (FGDs). Mantel-Haenszel test revealed that cancer screening uptake was positively associated with decreased social exclusion [OR 1.785 at 95% C.I 1.390-2.291, p <0.001] and better social network [(Emotional loneliness OR 5.791 at 95% C.I 1.384-24.225, p .016) (Social loneliness OR .200 at 95% C.I .114- .351, p <0.001)]. This study therefore found an association between general social factors and cancer screening uptake.

Keywords: Social factors, Uptake of screening, Early detection, Cancer

Cite this paper: Bornventure Paul Omolo, Sherry Oluchina, Serah Kaggia, Social Factors Associated with the Uptake of Screening Services for Early Detection of Cancer in Masinga Sub-County, Machakos County, Kenya, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 11 No. 3, 2021, pp. 56-61. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20211103.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of the Study

- The most cost-effective and long-term strategy for the control of cancer and other diseases is through prevention which requires major lifestyle changes. Behavioral processes can cause or prevent cancer and include not only tangible behaviors such as tobacco use but also a range of behavioral processes such as responses to stress, social interaction and group dynamics. Interactions among these health behaviors such as smoking, alcohol intake and psychosocial aspects such as stress, chronic depression and lack of social support may be related to cancer progression [1]. These health behaviors are intimately linked together by social processes such as peer relationships and socioeconomic status [2]. There is some evidence that social factors may affect uptake of cancer screening. For instance, living with a partner or being married, social support and social participation are all associated with uptake of breast cancer screening, however social isolation and poor sense of control are associated with lower uptake [3,4]. Similarly, social variables can also influence attendance through mechanisms such as social norms and perceived sense of responsibility towards self, family or society [5]. Social networks can offer practical, financial, emotional and social support, which may in turn facilitate preventive actions like cancer screening.Globally, it is estimated that there were 18.1 million new cancer cases and 9.6 million deaths in 2018; majority of these cases occurring in low-and middle-income countries [1,6]. In sub-Saharan Africa alone, the proportion of cancer burden is projected to have a greater than 85% increase by 2030 [8] and a substantive global increase of 19.3 million new cancer cases per year by 2025 [9]. In Kenya, the International Agency for Research in Cancer [1] report estimated 47,887 new cases of cancer annually with a mortality of 32,987. Cancer is estimated to be the third leading cause of death after infectious and cardiovascular diseases in Kenya; among the non-communicable diseases (NCDs) related deaths, cancer is the second leading cause of death representing 7% of overall national mortality after cardiovascular diseases [1].According to WHO [1], between 30-50% of cancer cases are preventable. Prevention of cancer, especially when integrated with the prevention of other related chronic diseases and programs within healthcare such as sexual and reproductive health, existing Human Immunodefiency Virus (HIV), immunization and maternal health will offer the greatest public health potential, and the most cost-effective long-term method of cancer control [6]. Moreover, study findings on lifestyle changes in cancer prevention reported that between 90% and 95% of all cancers have their origin in the environmental and lifestyle factors such as tobacco (25-30%), diet (30-35%) and infections like human papilloma virus (15-20%) [9]. Reduction of these risk factors provide significant opportunity to decrease the incidence and burden of the disease.Screening tests, as secondary prevention, offer a chance to detect cancer at an early stage when successful treatment is most likely. Low screening uptake and late treatment contributed to more than 85% of women’s death in low and middle-income countries [10] with death rates varying from country to country. This is due to inadequate access and uptake of screening services for prevention and early detection of the disease [11]. Holle and Pharm [12] therefore suggest that patients should be screened for cancer to detect precancerous lesions and their subsequent early removal. Notably, American Cancer Society [13] highlighted that social barriers can affect an individual’s capability for early cancer screening. Successful cancer prevention and control strategy hinges on the effective application of what is known about the basics of human behavior and social aspects. In Masinga sub-county, accurate information and statistics about these aspects are unknown due to lack of cancer registry, therefore relatively little is known about the extent to which they are associated with screening services.

1.2. Research Objective

- To determine social factors associated with the uptake of cancer screening services in Masinga sub-county, Machakos county, Kenya.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

- The study utilized both qualitative and quantitative designs (mixed study design) because of its ability to collect rich, comprehensive data and that permits a more complete and more synergistic data utilization. The study used a case-control study design. Cases comprised of those who were aware of cancer screening and had been screened while controls comprised of those who were aware and have never been screened. The study lasted for a period of three months.

2.2. Sampling and Recruitment Procedure

- This study utilized systematic sampling method. It involved a random start, chosen from within the first to the kth patient. There were two groups who got interviewed: 42 cases (aware and screened) and 116 controls (aware and unscreened) at a ratio of 1:3. For cases, k was every 9th person and for controls, k was every 12th. Inclusion criteria among cases was residents of Masinga sub county; men and women who were 18 years and above seeking various services at Masinga level 4 hospital, outpatient department; and those who had been screened before, while for controls it was residents of Masinga sub county, men and women who were 18 years and above seeking various services at Masinga level 4 hospital, outpatient department and those who had never been screened before. Participants who had major disabling medical or psychiatric conditions and were unable to effectively cooperate during the interview were excluded from the study. As for focus group discussion (FGD) guide, a random sampling technique was used where a total of three FGDs out of four for cases, and six out of nine for controls were conducted as saturation was already reached. Each FGD comprised of twelve people.

2.3. Data Management

- The questionnaires were coded for ease of data entry. All the raw data were reviewed by the researcher and cross-checked to ensure data completeness. Data was then entered in Microsoft excel where cleaning and editing was done and then imported to SPSS version 26.0 for analysis. Mantel-Haenszel was used to generate odds ratios and to determine the strength of association; Chi square and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to determine the statistical significance between independent and the outcome variable. Hypothesis testing was done at an alpha level of significance of 0.05 such that any p-value below the alpha was deemed significant. The qualitative data were then used to support the outcome of the quantitative data as well as develop grounded theories for basing study conclusions. Data was presented using tables and narratives and was described using mean and frequencies. Qualitative data was analyzed thematically.

2.4. Ethical Consideration

- Research permits and approvals were sought from all relevant institutions in the study. Voluntary and informed consent of the respondents was sought after explaining the aim of the study and the procedures involved. Confidentiality of the information given by the respondents was emphasized and participants assured that the information provided was for academic purposes only. The identities of the respondents were protected by using numbers to ensure the principle of anonymity. The principles of beneficence, respect for persons/human dignity and justice were also observed during the study. Furthermore, authors do not have conflicting or competing interests towards the publication of this study.

3. Results

3.1. Response Rate

- The response rate was 99% (n=155) from the questionnaires. From the focus group discussion (FGD), the response rate was 69.2%; nine FGDs were conducted instead of thirteen since saturation had already been reached.

3.2. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

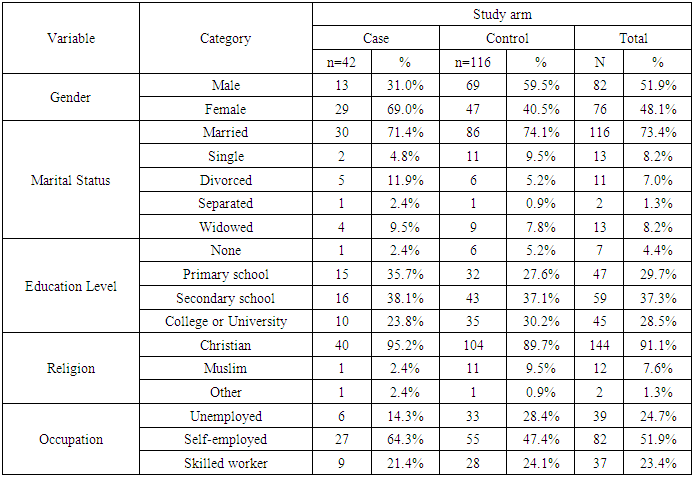

- The study comprised of 26.6% (n=42) cases and 73.4% (n=116) controls. The mean age of cases and controls was 44.3 (±11.1) and 42.8 (±14.8) years respectively. Table 3.1 shows the distribution of sociodemographic factors among the study participants.

|

3.3. Association between Social Factors and Cancer Screening Uptake

- The main financial support system for cases was NHIF 52.4% (n=22) while for controls it was family support 23.3% (n=27), NHIF 37.1% (n=43), and out-of-pocket 39.7% (n=46). Both cases and controls mainly covered an approximate distance of less than ten kilometers from home to the hospital [83.3% (n=35) and 77.6% (n=90) respectively]. For both cases and controls, outreach programs organized on cancer screening by the health facilities were low at 47.6% (n=20) and 25.9% (n=30) respectively. This was defined as ‘rarely’ 47.6% (n=20) and ‘often’ 0.9% (n=1). Mode of transport to and from the hospital for cases and controls was mainly public Transport; 76.2% (n=32) and 83.6% (n=97) respectively. According to 71.4% (n=30) of cases and 19.8% (n=23) of controls, cancer screening equipment were available in hospitals. Most cases at 54.8% (n=23) cited that the cancer equipment were functional in contrary to controls who did not know of the functionality of the equipment.

3.3.1. Social Network

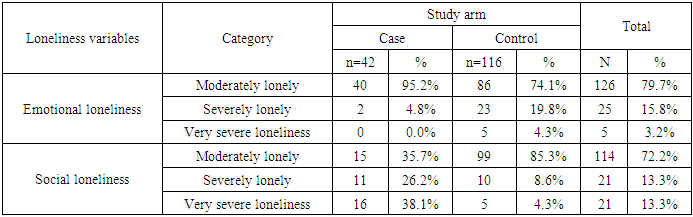

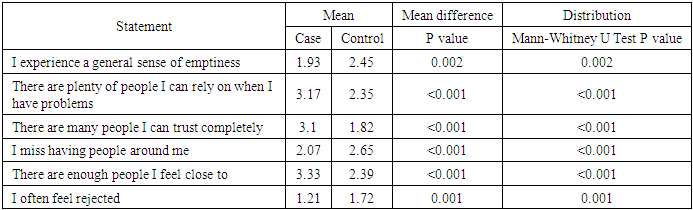

- Social network was measured using De Jong Gierveld loneliness scale. Table 3.2 shows descriptive statistics results for emotional and social loneliness, while table 3.2.1 shows mean difference among cases and controls using Mann-Whitney U test.

|

|

|

|

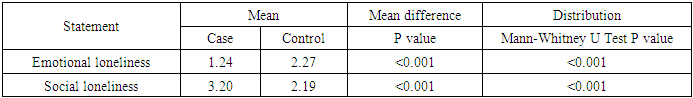

3.3.2. Social Exclusion

- Social exclusion, the feeling that one does not belong to the society, was measured using a scale developed by Bude and Lantermann (2006). Table 3.3 presents Mann-Whitney U test results showing mean difference for perceived social exclusion among cases and controls.

|

|

3.4. Qualitative Data

- The following are themes and narratives from the focus group discussions (FGDs) on how social life influenced cancer screening:1. Decision maker in the family: - “My husband would inquire why I’m leaving the house every time, so I wouldn’t want to mention something like cervical cancer screening because then he may suspect that I have been cheating on him.” …participant 2 of FGD 1. “My husband pays for all medical bills and he always feels going for such services when one is not sick isn’t a priority.” …participant 4 of FGD 2.2. Influence from family and friends: -“Well, they say that the speculum used may interfere with the size of my vagina. That really scared me.” …participant 1 of FGD 2. “I never thought of it before. It was my friend who asked me to accompany her for screening, and in the process, I also decided to be screened for breast cancer.” …participant 3 of FGD 1. “A friend once told me how they did prostate cancer screening on him and how embarrassing it was. Scientists need to device a friendlier method. I never wanted to go through the same because it is embarrassing for men.” …participant 11 of FGD 2.“My eldest brother who is a dentist encouraged me to go for colonoscopy after he was diagnosed with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) because it runs in families and is a major predisposing factor to colon cancer.” …participant 2 of FGD 5.3. Public campaigns: - “I got this information during the international breast cancer day on one of the national TV stations. My sister and I made a decision to be going for cervical cancer screening every five years” …participant 7 of FGD 4.

3.5. Discussion

- The analysis of disease trajectory for specific detectable diseases such as cancer provide means to pin-point evidence-based intervention strategies that can be used to reduce the morbidity and mortality rates. Delays in seeking care, diagnosis and commencing treatment add to the lag time between disease onset and treatment which ultimately impact on survival significantly. Delays in seeking care have been reported in the past in a study done by Onyango and Macharia [14] at Kenyatta national hospital which had similar findings with another study done by Were et al. [15] at Moi teaching and referral hospital. Patient delays may be attributed to lack of awareness, unfavorable socioeconomic backgrounds and healthcare system with regard to screening and prevention. This study therefore aimed at examining the association between the use of cancer screening for early detection and general social factors. Among the social factors assessed, social network, which examined loneliness level; and social exclusion were found to be associated with uptake of cancer screening. Cases had significantly lower levels of loneliness and social exclusion as compared to controls which could be an explanation why they participated in cancer screening at a higher level. These findings were supported by a study done by Lagerlund et al. [5] on psychosocial factors and attendance at a population-based mammography screening program in a cohort of Swedish women. Another study in India by Wu et al., [16] also noted that care providers, family and friends positively influenced breast cancer screening. Locally, there are no studies examining the social factors associated with cancer screening uptake. Moreover, the distribution of awareness of health facilities organizing for outreach programs on cancer screening of cases and controls was significantly different in that the cases reported having had more of the medical outreaches than the controls. Besides, cancer screening equipment availability in hospitals was another significant factor whose awareness among the respondents was higher in cases. These factors can be attributed to screening uptake in cases. Focus group discussions also highlighted three main themes: (1) decision maker in the family; (2) influence from family and friends; and (3) public campaigns, as some of the factors that either positively or negatively influenced uptake of screening. Men being the main decision makers in the family would dictate when women in these families would seek which services and this would most likely be one of the reasons for low uptake. Influence from family or friends carried with it myths that negatively impacted the uptake. Some would term the procedures during screening as embarrassing and painful which probably would discourage a number of those willing to take up the services.

4. Conclusions

- Notably, from the findings of this study, social network (p <0.05) and social exclusion (p <0.001) were found to be associated with uptake of screening.People often face significant barriers coupled with inadequate knowledge that result in late presentation, hence increased morbidity and mortality. The ultimate goal of early detection and prevention is to eliminate, reverse or reduce one’s risk of developing or dying of cancer emanating from these barriers and knowledge deficit. The findings of this study can therefore be used to develop specific interventions that are tailored to meet the unique sociodemographic needs of the locality. This requires an extensive understanding of the population and risk-based associations with cancer. For instance, knowledge on human behavior presents several avenues for targeted and sustained intervention to ensure significant reduction in cancer morbidity and mortality; psychosocial experiences on the other hand are known to increase the risk of some cancers yet people are often quite resistant to change. Even though cancer diagnosis and treatment has substantially progressed into precision medicine initiatives, cancer screening and prevention in Kenya has not caught up with the advances. Nevertheless, early detection and prevention of cancer should adapt techniques which fits in precision prevention initiatives touching on the aforementioned barriers. Understanding general social factors that are associated with cancer screening uptake might be fruitful to address individuals at high risk of cancer development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- To my supervisors for their guidance all through the study period. In addition, to Masinga level 4 hospital for the permission to undertake this study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML