-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2018; 8(6): 108-114

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20180806.02

Nursing Students’ Academic Performance in a Clinical Practice Course and Perceptions of Their Clinical Experience in Hospitals in Two Parishes in Jamaica

Andrea Pusey-Murray1, Cynthia Onyefulu2

1College of Health Sciences, University of Technology, Jamaica

2Faculty of Education and Liberal Studies, University of Technology, Jamaica

Correspondence to: Andrea Pusey-Murray, College of Health Sciences, University of Technology, Jamaica.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In nursing programmes, students are exposed to both theoretical and practical components. The main purpose of this study was to determine the academic performance of the nursing students in the clinical practice course during the 2017/2018 academic programme in a university in Jamaica. The study is also designed to investigate their perceptions of their clinical practice placement and to determine if there was a significant relationship between the students’ perceptions and their performance in the clinical practice course.An ex-post-facto design was used in the study. One hundred and seven Jamaican nursing students (3 males & 104 females) who were enrolled in a four-year degree nursing programme were purposefully selected for the study. A questionnaire which had a reliability coefficient of 0.87 was used to collect data from the nursing students. The nursing students who participated in the study completed at least 40 hours of clinical practice in the different units of the hospitals. These include the renal unit, medical ward, surgery ward, the psychiatric ward, and the maternity ward. Travelling was the main problem for the students who travelled for an average of 52.5 minutes to where they were posted. Approximately 88% used public transportation. The mean score for the academic performance of the nursing students was 80%. Approximately 40% of the nursing students felt that the patients were disrespectful. Seventy-four (69%) of the nursing students indicated that they would remain in the nursing profession after their training. There was a weak, positive relationship between nursing students’ perceptions and their performance in the clinical practice course (r = 0.23; n= 107, p =.017).Based on the findings, recommendations were made on how to address the issues encountered by the nursing students during their clinical practice, and how to continue to promote the intrinsic values of becoming a nurse so that more nursing students would want to remain in the profession.

Keywords: Nursing Students, Clinical Experience, Remaining in Nursing

Cite this paper: Andrea Pusey-Murray, Cynthia Onyefulu, Nursing Students’ Academic Performance in a Clinical Practice Course and Perceptions of Their Clinical Experience in Hospitals in Two Parishes in Jamaica, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 8 No. 6, 2018, pp. 108-114. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20180806.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- In nursing programmes, students are exposed to both theoretical and practical components. The combination of theory and practice in the clinical setting is seen by Mabuda, Potgieter, and Alberts (2008) as the “art and science of nursing” (p. 19). Clinical learning is a vital component of nursing education. In addition to providing opportunities to develop competence in nursing skills, the clinical environment engenders in nursing students a sense of identity as professionals in the real world. This is because to complete the practical component of their training; the nursing students are assigned to a hospital or clinic under the supervision of experienced nurse practitioners and/or educators. Clinical supervision is defined as “a process of professional support and learning in which nurses are assisted in developing their practice through regular discussion time with experienced and knowledgeable colleagues” (Fowler, 1996, as cited in Brunero & Stein-Parbury, 2008, p. 87). Brunero and Stein-Parbury (2008) stated that clinical supervision “provides nurses with the opportunity to improve patient care in particular for a given patient and in general in relation to maintaining standards of care” (p. 87). For clinical learning and supervision to occur successfully, Mabuda, Potgieter, and Alberts (2008) appointed to the need for the clinical environment to be conducive to learning as well as to be supportive. This is because such an environment would have an effect on nursing students’ achievement and satisfaction (Mabuda, Potgieter, & Alberts, 2008).The nursing students in this study are required to complete a seven-week clinical practice course in a hospital setting. This course is designed to provide an opportunity for nursing students to put into practice the theoretical knowledge learnt in their training. During this period, the nursing students are mentored, supervised, and assessed during their clinical practice course.

1.1. Statement of the Problem

- Since the inception of the nursing programme at the institution used for the study, nursing students are assigned to hospitals for seven weeks clinical experience. When asked by their supervisors during and after their posting, these nursing students share their views of their clinical environment, their encounters with the patients and their relatives, and their successes and challenges. Despite the nursing students’ informal responses, as well as their performance at the end of the course, there has not been any formal quantitative research done on this topic.A review of the literature shows that a few studies have been done in this area around the world. For instance, in Africa, Adjei, Sarpong, Attafuah, Amertil, and Akosah (2018) explored the perceptions of student nurses in a private university in Ghana. Similarly, Mabuda, Potgieter and Alberts (2008) investigated the experiences of student nurses during clinical practice at a nursing college in Limpopo Province in South Africa.Studies have also been done in the Middle East by Sharif and Masoumi (2005) who explored nursing students’ experiences of clinical practice in Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in southern Iran; while Jamshidi, Molazem, Sharif, Torabizadeh, and Kalyani (2016) examined the challenges of nursing students in clinical learning Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in Iran. Other studies were done by Tiwaken, Caranto, and David (2015) who examined the lived experiences of student nurses during clinical practice in Bonafide Benguet State University-College of Nursing in the Philippines in Asia. While in Europe, Mattila, Pitkajarvi, and Eriksson (2010) studied the clinical practice experiences of international student nurses in the Finnish health care system. In all these studies done in different parts of the world, the researchers used mostly the qualitative approach to explore nursing students’ experiences during and/or after clinical practice.Furthermore, several studies examined nursing students’ academic performance by using the quantitative approach; however, most of these studies centred around factors that affect nursing students’ academic performance. Academic performance is defined as the “ability of students to cope with their studies as well as how various tasks assigned to them by their instructors are accomplished” (Elsabagh & Elhefnawy, 2010, p. 46914). These include but not limited to studies done by Blackman, Hall, and Darmawan (2007), Elsabagh and Elhefnawy (2017), Dimkpa, Daisy, Inegbu, and Buloubomere (2013), Stomberg and Nilsson (2010), and Sunshine, Alos Lawrence, and Caranto (2015). Although these studies mentioned above used the quantitative approach, others mentioned previously showed the limited use of the quantitative approach in investigating nursing students’ academic performance and experiences in a clinical practice course. Hence, this study was designed to fill this gap in the existing literature.

1.2. Purpose of the Study

- The main purpose of this study was to use the quantitative research approach to determine the academic performance of the nursing students in the clinical practice course during the 2017/2018 academic programme, as well as investigate their perceptions of their clinical practice placement.

1.3. Objectives of the Study

- 1. To identify issues encountered by the nursing students during their clinical practice placement.2. To determine how the nursing students resolved these issues.3. To determine if there is any significant relationship between the students’ perceptions and their performance in the clinical practice course.

1.4. Significance of the Study

- It is believed that the study will provide results on the clinical placements and experiences of the nursing students that will be beneficial to different stakeholders (nursing educators & students). First, the nursing educators at the institution used for the study may find the results useful since it will reveal the nursing students’ perceptions of their clinical practice experience, and possible ways of improving areas of weaknesses. Second, by fixing problem areas in the course, it might enhance the learning experience for the nursing students in the future.

1.5. Research Questions

- The following research questions guided the study:1. How well are the nursing students performing academically in the clinical practice course?2. What issues, if any, did the nursing students’ experience during their clinical practice placement?3. To what extent is there a significant relationship between the nursing students’ perceptions and their academic performance in the clinical practice course?

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Sampling

- An ex-post-facto design was used in the study. A purposeful sampling method was used to select 107 students who were placed in hospitals in two parishes (Kingston and St. Catherine). These students were enrolled in a four-degree nursing programme at a university in Jamaica.

3.2. Data Collection

- Two sets of data were collected. First, data were collected through the use of a questionnaire, with an internal consistency of 0.87. This is considered adequate because the value is above the 0.70 criterion as recommended by Bryman and Cramer (2011).

3.3. Ethical Considerations

- Only the nursing students who agreed to participate were asked to complete a consent form before completing the questionnaire. Second, students’ final grades were used to determine their academic performance in the clinical practice course. No names were assigned to the grades in order to keep their identity of the participants private. Furthermore, the university ethics committee approved the ethical clearance submitted by the researchers before the study was conducted.

3.4. Data Analysis

- Data collected were coded and entered into the SPSS program (version 21), and the analyses were done through the use of univariate statistics (frequency, mean, & standard deviation), and bivariate statistics (Pearson Product Moment correlation).

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

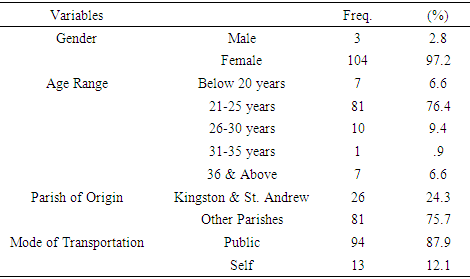

- The sample characteristics are reported first. This is followed by the findings according to the research questions. See Table 1 for the demographic information about the nursing students.

|

4.2. Nursing students’ Academic Performance in Clinical Practice

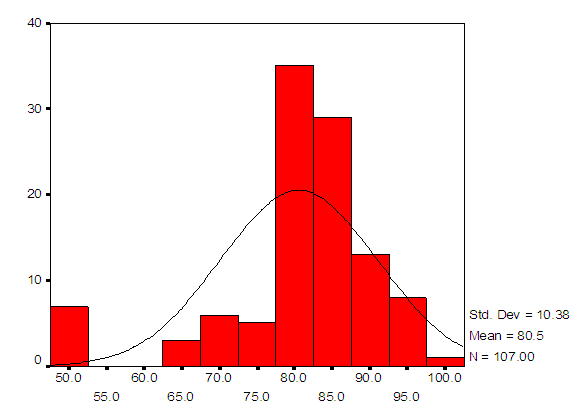

- Research Question One: How well are the nursing students performing academically in the clinical practice course?The nursing students’ final score in the clinical practice course was used to provide answers to this research question. The findings showed that the highest score was 98% while the lowest was 50%. The mean score was 80.0% with a standard deviation of 10.4, indicating a wide variation in the students’ final scores. Furthermore, the distribution of the scores was negatively skewed. The skewness value was -1.51 with a standard error of 0.23. This showed that there are a few students who scored below the 80% average. See Figure 1.

| Figure 1. Nursing Students’ Final Score in a Clinical Practice Course |

4.3. The Nursing Students’ Experiences in the Clinical Practice

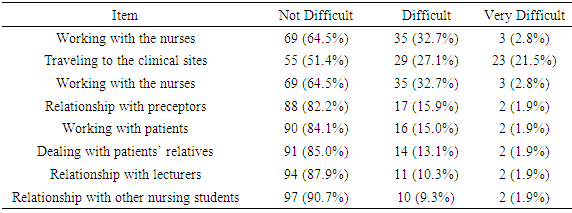

- Research Question Two: What issues, if any, did the nursing students’ experience during their clinical practice placement?The questionnaire and the nursing students’ final score in the clinical practice course were used to provide answers to this research question. The nursing students were asked if they were nervous during the clinical practice period. Sixty-six (61.7%) said yes, while 41 (38.3%) said no. They were also asked to identify what made them nervous. Of the 107 surveyed, 64 (59.8%) responded to this item. The following themes emerged from the analysis: (a) 30 (46.9%) expectations, (b) 22 (34.4%) not enough practice, (c) 10 (15.6%) being assessed, and (d) two (3.1%) other difficulties such as safety and lack of resources. The findings also showed that a few of the nursing students indicated that they received instructions different from what they were taught in the classroom.From a list provided on the questionnaire, the nursing students were also asked to identify what was more difficult for them during the clinical practice period. As shown in Table 2, two main difficulties experienced by the nursing students were working with the nurses (32.7%) and travelling to the clinical sites (27.1%).

|

|

|

4.4. The Nursing Students’ Perceptions and Their Academic Performance

- Research Question Three: To what extent is there a significant relationship between the nursing students’ perceptions and their academic performance in the clinical practice course?To examine if there was a significant relationship between nursing students’ perceptions and their academic performance in the clinical practice course, the Pearson Correlation was computed. The obtained coefficient was 0.23; at the significance level of .017. The number of participants with both variables was 107. The direction of the relationship was positive. Using the Ravid’s (2005) guidelines, the relationship was weak.

5. Discussions

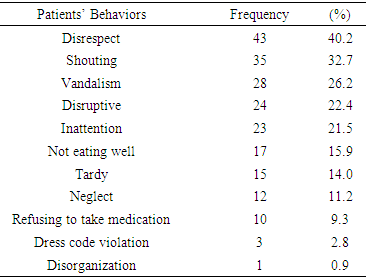

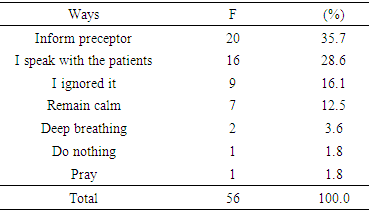

- Regarding the findings to research question one, with an average of 80%, and a negatively skewed distribution, the nursing students’ academic performance was good. However, with a standard deviation of 10.4, it showed that there was a wide variation in the students’ final scores. This variation could be associated with factors which were previously investigated by Blackman, Hall, and Darmawan (2007), Elsabagh and Elhefnawy (2017), Dimkpa, Daisy, Inegbu, and Buloubomere (2013), Stomberg and Nilsson (2010), and Sunshine, Alos Lawrence, and Caranto (2015). Furthermore, Msiska, Smith, and Faecett (2014), Motiagh, Karimi, and Hasanpour (2012), and Mabuda, Potgieter, and Alberts (2008) supported these findings. Regarding the findings to research question two, during the clinical practice, the nursing students experienced some challenges in the clinical sites. These include working with nurses (32.7%), travelling to the clinical site (27.1%), working with patients (15%), and dealing with patients’ relatives (13%). In this study, the nursing students were in the third year of their programme, and 61.7% said they were nervous during clinical practice. From the responses provided, the following factors were said to have contributed to their nervousness: (a) expectations (46.9%), (b) not enough practice (34.4%), (c) being assessed (15.6%), and (d) other difficulties such as safety and lack of resources (3.1%). Furthermore, 46.9% of the nursing students attributed their nervousness to “expectations” of them being in the clinical areas. The findings also showed that during the clinical practice, the nursing students received instructions different from what they were taught in the classroom. The differences between the instructions given by the lecturers to the nursing students during the clinical practice course and those provided by the preceptors at the time of their clinical practice warrant further investigation since it has an implication for their professional practice. According to Spurlock (2006), the teaching faculty has the responsibility of providing quality instruction. Developing competent and confidence among student nurses is an important component of the nursing practice, and the nurse educators should facilitate the process by providing clear and consistent instructions to their students. Positive clinical experiences can impact positively on student nurses’ feelings (Pearcey & Dapper, 2008). This again emphasises the importance of utilising clinical facilitators who are competent and skilled to guide nursing students. The findings of this study also showed that 15.6% of the nursing students stated that being assessed at the ending of their clinical experience contributed to their nervousness. Students’ feelings of incompetence can be reduced by creating a climate for learning where they would have received ample guidance during their clinical experience. Hence, reducing the increase in tensions brought about by being assessed. One percent of the respondent highlighted the lack of resources which contributed to their nervousness. This finding is consistent with a study by Magnussen and Amundson (2003) which showed that insufficient hospital resources, unprepared work environment, and financial constraints are the most stressful experiences to the nursing students. Inadequate clinical supervision and guidance by the nurses in the clinical area raised concerns among nursing students. Approximately 82% of the nursing students in this study stated that their relationship with the preceptors was not difficult. A similar finding was observed by Salamonson et al. (2015) who stated that students regarded clinical facilitators as supportive and accessible for their learning. Furthermore, approximately 31% of the nursing students stated that they are likely to leave the profession after their training. Although the percentage of those who indicated to remain in the nursing programme is higher, the finding may have serious implications for the healthcare sector in Jamaica. This is because there is already a high rate of migration among specially trained nurses in Jamaica, which has resulted in the shortage of nurses (Thompson, 2015). In a systematic review done by Eick, Williamson, and Heath (2012), they stated that clinical experience is one of the factors why nursing students decide either to discontinue or continue their training. For other factors, see Urwin, Jones, Gallphar, Wainwright, and Perkins (2010), and Mansour, Gemeay, Behilak, and Albarrak (2016).Regarding research question three, there was a weak positive relationship (r = 0.23) between nursing students’ perceptions and their performance in the clinical practice course. Due to the variables used in this study (perceptions & academic performance), no previous studies were found to support these findings. However, it is important to note that several others have examined nursing students’ academic performance. These include but not limited to studies done by Blackman, Hall, and Darmawan (2007), Elsabagh and Elhefnawy (2017), Dimkpa, Daisy, Inegbu, and Buloubomere (2013), Stomberg and Nilsson (2010), and Sunshine, Alos Lawrence, and Caranto (2015).

6. Conclusions

- The main aim of this study was to determine the academic performance of the nursing students in the clinical practice course during the 2017/2018 academic programme, as well as to investigate their perceptions of their clinical practice placement. The nursing students’ academic performance in the clinical practice course was good. However, the main problem experienced by the students was travelling to the clinical sites. Furthermore, the nursing students encountered some behavioural problems which were from their patients during the clinical practice period. Some of the nursing students notified their preceptors about their encounters. There was a weak, positive relationship between the nursing students’ academic performance in the clinical practice course and their perceptions. The importance of clinical practice course in nursing education cannot be overemphasised. It is through clinical teaching and practice that nursing students learn how to apply abstract concepts in specific and concrete situations in the clinical sites.

7. Limitations

- The current study has two main limitations. First, the sample for the study comprised of 107 participants, which did not represent the entire population of nursing students in the university. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalised to all the population of nursing students in the university studied. Secondly, the study relied only on the use of a questionnaire for data collection, which did not allow for probes. These limitations notwithstanding, it is believed that the findings will contribute to the existing literature in this area.

8. Recommendations

- Based on the findings, the following recommendations are made:1) The managers of the nursing programme should pay attention to the few students whose scores were far below the average score of 80%. This is to ensure that the students are competent in the clinical practice course before they leave the programme. 2) In the curriculum, the nursing students should be given more opportunities to practice before they go on clinical practice in the hospitals. This may enable them to have more hours of practice and reduce nervousness. 3) To ensure that the quality of instructions given to the nursing students during clinical practice course is high, the managers of the nursing programme should address the differences in the instructions received by the students from their instructors and the preceptors.4) The managers of the nursing programme should make efforts to address the transportation problem which was experienced by a majority of the nursing students who participated in the current study. This may involve getting a university bus to transport nursing students.5) The instructors of the clinical practice course should devise a means of providing more information to the nursing students on how to better deal with patients’ behaviours. 6) More attention should be given to the nursing students who may decide not to continue their training. This could be done by the programme managers who should determine the attrition factors and ways of addressing them.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML