-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2018; 8(5): 83-92

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20180805.02

Effect of a Nutritional Education Program on Nutritional Status of Elderly in Rural Areas of Damanhur City, Egypt

Amal Yousef Abdelwahed1, Magda Mhmoud Mohamed Algameel2, Dalia Ibrahim Tayel3

1Community Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Damanhour University, Egypt

2Gerantological Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing Damanhour University, Egypt, College of Applied Medical Science, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, KSA

3Nutrtion Department, High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt

Correspondence to: Magda Mhmoud Mohamed Algameel, Gerantological Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing Damanhour University, Egypt, College of Applied Medical Science, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, KSA.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

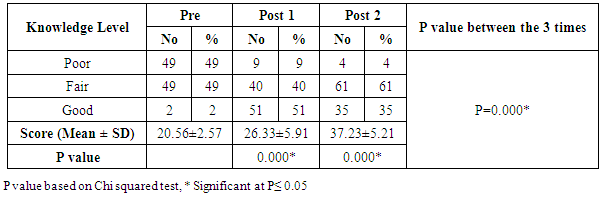

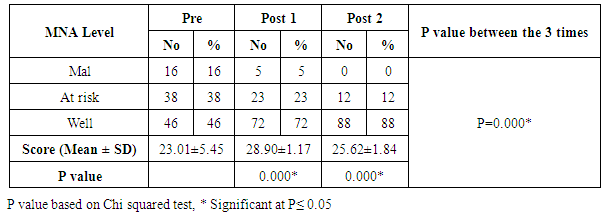

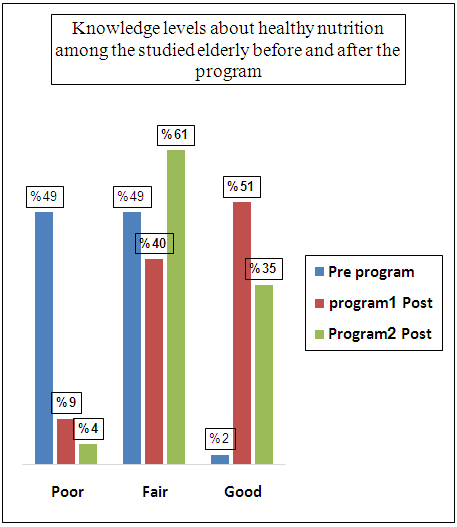

Background: Older adults are at an increased risk of inadequate diet and at risk of malnutrition. Poor nutritional status is associated with increased demands on health services, lengthier hospital stays and it is recognized as an important predictor of morbidity and mortality. Strategies for effective nutritional intervention should be implemented to prevent and treat malnutrition. Objective: The study aimed to assess the effect of a nutrition education program on the nutritional status of elderly in rural areas in Damanhur city. Subjects and Methods: One group pre-test post-test intervention study was carried out on 100 elderly at rural health unit namely Zarkon village, Damanhur city, Egypt. Data about socioeconomic characteristics, medical history, and life style were collected by interviewing. Nutrition educational program was implemented on 6 consecutive sessions, 6 days per week, and two sessions per day. Duration of each session ranged from 1-2 hours. The elderly persons were divided into 10 groups (each group in elderly contains 10 client). Healthy Nutrition Scale and Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) were used to assess the knowledge about healthy eating and proper nutrition for elderly, and the nutritional status of elderly and determine the risk of malnutrition, respectively three times, before, immediately after the end of the programme, and 3 months later to evaluate the immediate and retained changes in elderly. Results: Less than half (49%) of the elderly had poor nutritional knowledge before the educational program compared to 9% and 4% of them in the immediate post program evaluation and three months follow up respectively. None of the elderly were malnourished in the second evaluation after 3 months compared to 5% immediately after the program and 16% before the program. Conclusion: The education program was very effective in enhancing the nutritional status of the elderly as well as the nutritional knowledge of them.

Keywords: Malnutrition, Older adults, Knowledge, Damanhur, Egypt

Cite this paper: Amal Yousef Abdelwahed, Magda Mhmoud Mohamed Algameel, Dalia Ibrahim Tayel, Effect of a Nutritional Education Program on Nutritional Status of Elderly in Rural Areas of Damanhur City, Egypt, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 8 No. 5, 2018, pp. 83-92. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20180805.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The percentage of the elderly is growing rapidly worldwide. The global number of the elderly is projected to rise from an estimated 900 million to 2 billion between 2015 and 2050 (moving from 12% to 22% of the total global population), with most of this increase in developing countries [1]. The factors underlying this transition are increased longevity, declining fertility, and advances in health care [2, 3] In Egypt, the elderly population is growing rapidly and constituted around 10% of the total population according to the EDHS 2015 [4]. Such a rapid rise in the elderly population will definitely pose several challenges. The lack of guaranteed sufficient income, the absence of social security, loss of social status and recognition, and persistent ill health are some of the daunting problems the elderly face [2].Aging is a physiological process continues throughout life, and ends with death. Among numerous factors that modulate ageing, nutrition plays a significant role. Older adults are at an increased risk of inadequate diet and malnutrition, and the rise in the older population will put more patients at risk [5, 6]. While poor nutrition is not a natural concomitant of ageing, older adults are at risk of malnutrition due to numerous risk factors. Aging is associated with a decline in number of physiological functions that can affect nutritional status, including reduced lean body mass, changes in hormonal levels, delayed gastric emptying, changes in fluid electrolyte regulation, and diminished sense of smell and taste. Pathological causes such as chronic illness, depression, medications and social isolation can all play a role in nutritional inadequacy [7-9].Malnutrition is a serious and frequent condition in elderly. The prevalence of malnutrition is reported to be 18–30% in different populations of elderly people in need of health care services [10-13]. Inadequate diet and malnutrition are associated with a decline in functional status, impaired muscle function, decreased bone mass, immune dysfunction, anemia, reduced cognitive function, poor wound healing, and delay in recovering from surgery, and higher hospital and readmission rates and mortality [8, 14]. Malnutrition can adversely affect the well- being of older persons mainly by causing a decline in functional status, worsening of existing medical problems and even increasing mortality rates [6, 15]. Malnourished elderly persons are more likely to require health and social services, need more hospitalization, and demand extra challenges from caregiver. So, early detection and prompt interventions are essential for prevention of malnutrition in this group [16, 17].An essential strategy for keeping older people healthy is preventing chronic diseases and reducing associated complications, including malnutrition. To assist with dietary changes and transference of information, nutrition education programs should be developed targeting older people. In addition, tailoring programs to specific subgroups of the older population would enhance the effectiveness of nutrition education. To be more effective, the health care providers including the nurses should identify the older people dietary needs and integrate the nutrition message within people’s living context and background. Thus, it will help older people to remain independent longer, improve their nutritional status and quality of life, potentially delay the need for long-term care, slow the expected growth of health care and long-term costs for this and future generations [18, 19].To support the need for such screening, the aim of the study was to assess the effect of nutrition educational program on the nutritional status of elderly in rural areas in Damanhur city, Egypt.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

- A one group pre-test post-test intervention study was carried out from January 2017 to May 2017 on 100 elderly (aged 60 or above and able to participate in the study) at rural health unit namely Zarkon village the biggest village affiliated to Damanhur city, Egypt. The sample size was calculated statistically using Epi info 7 statistical program assuming a 25% prevalence of malnutrition among old adults; using 95% confidence level with 5% maximum error. The minimum sample size estimated to be 100 subjects. Elderly were selected randomly from the village till fulfilling the required sample size. Each subject informed about the purpose of the study and their verbal consent was obtained.

2.2. Data Collection and Study Questionnaire

- In order to collect the necessary data for the study three tools were used:Tool (I): Elderly persons’ basic data structured interview schedule:It was developed by the researchers to collect the necessary data from elderly. It included the following data: elderly’ personal and socio-economic characteristic (age, sex, level of education, occupation, income, living condition, and marital status), elderly’ medical history and lifestyle data (the presence of diseases, teething problems, smoking type and frequency, physical activities and exercises type and duration, and eating during watching TV), and food choice and preparation.Tool (II): Healthy Nutrition Scale:This scale was developed by the researchers after reviewing of thorough relevant literatures [6, 10, 12, 14]. It was used to evaluate elders' knowledge about daily dietary requirement and healthy, balanced diet. It contained 27 statements about importance of food, component of balanced diet, daily fluid and food requirements, resources of vitamins, minerals and other food elements as well as causes of malnutrition. Responses to each statement were incorrect, somewhat correct/complete or correct/complete. A correct complete answer was scored as (2), somewhat correct/complete was scored as (1), but the scoring of incorrect was (0). The total score was generated by summing up the scores from all statements. The resultant total score ranges from 0-54 where as those having a score of 0-17 were considered poor knowledge, and those with a score of 18-35 were considered fair knowledge while those with good knowledge have a score ranges from 36 to 54.Tool (III): Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA): [20]It is an instrument designed by Nestle Nutrition Institute specifically for elderly people. The MNA scale comprised 18 questions divided into 4 nutritional areas: anthropometric measurements (four questions about weight, height and body circumferences, with a maximum score of eight points), dietary questionnaire (six questions related to number of meals, kind of foods, fluid intake and autonomy of feeding, with a maximum score of nine points), global assessment (six questions according to lifestyle, medication and mobility, with a maximum score of nine points) and subjective assessment (self-perceived health and nutrition, with a maximum score of four points). The total score of MNA distinguished between well-nourished elderly (score ≥ 24), at risk of malnutrition (score 17- < 24) and malnourished ones (score < 17).Weight and height were measured for each subject at the time of interview according to the criteria of Gibson [21] Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the body weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. Overweight person was defined if BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2, and obese one was defined if BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, while a person was considered underweight if BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 [22].

2.3. Nutrition Educational Intervention Program

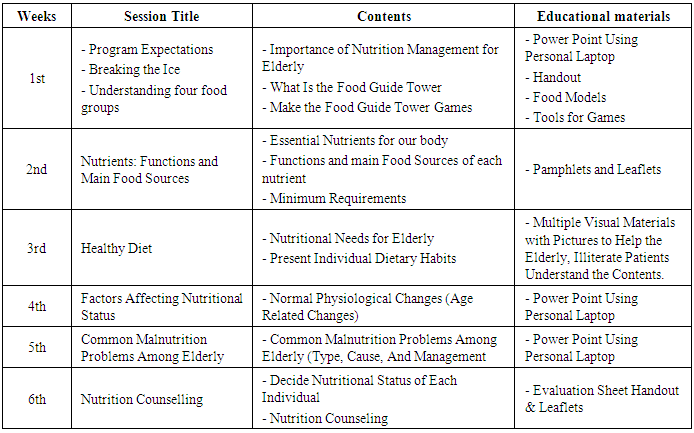

- I-Preparation phase: Initial assessment of each study subject in the previously mentioned settings using healthy nutrition knowledge scale was carried out before applying the educational program.II- Developmental phase: The program objectives and methodology were prepared based on reviewing of all relevant and recent literature [12].III- Implementation phase: Each elderly participated in the study was interviewed individually to collect the necessary data using the three tools. The program was conducted on 6 consecutive sessions, 6 days per week, two sessions per day for the different groups. Duration of each session ranged from 1-2 hours. The elderly subjects were divided into 10 groups (each group in elderly contains 10 client). For each group the program was conducting on 6 consecutive sessions along with 6 weeks, one section per day. Program expectations, breaking the ice, and nutritional needs for elderly health took 1 session for each. While healthy diet (function of each nutrient, and component of healthy diet) and common malnutrition problems among elderly (type, cause, and management) took 2 sessions for each. Components and schedule of educational program are illustrated as the following:

|

2.4. Ethical Considerations

- This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down for medical research involving human subjects and was approved by Ethics Committee of High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt. All measurements were taken following all privacy procedures and all collected data were kept confidential. Each participant was informed about the study purpose, and their verbal consent was taken. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- Tool (I) and (II) were developed by the researchers after reviewing the recent relevant literature. It was validated by juries of (5) experts in the field. Their suggestions and recommendations were taken into consideration. Cronbach Alpha Coefficient was used to ascertain the reliability of tool (II) and (III) after translation into Arabic language, (r=0.86 for tool II and 0.82 for tool III). Pilot study was carried out on 10 elderly people who were randomly chosen from a family health center not included in the sample namely, "Zawya Ghazal" in order to ascertain the relevance, clarity and applicability of the tools, test wording of the questions and estimate the time required for the interview. Based on the obtained results, the necessary modifications were done. After data were collected, they were coded and transferred into specially designed formats so as to be suitable for computer feeding. Following data entry, checking and verification processes were carried out to avoid any errors during data entry, frequency analysis, cross tabulation and manual revision were all used to detect any errors. The statistical package for social sciences (SPSS version 20) was utilized for both data presentation and statistical analysis of the results. The level of significance selected for this study was P equal to or less than 0.05.

3. Results

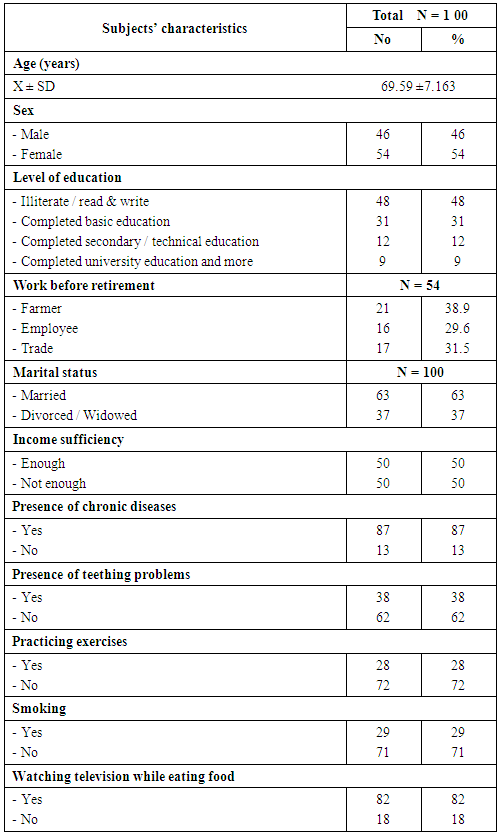

- Table 1 shows that more than half (54%) of the elders were females while the rest (46%) were males. The age of the elders ranged from 60 to 89 years with a mean of 69.59±7.163. Less than two thirds (63%) of the elders were married while the rest were widowed or divorced. Concerning their educational level, the tables shows that less than half (48%) of them were illiterate or just could read and write while those who completed their university education constituted 9%. On the other hand, 38.9% of the elders were farmers and 29.6% of them were employees before retirement. The table also portrays that half (50%) of the elderly reported income insufficiency and the majority (87%) of them had health problems including teething problems (38%). Moreover, the majority (82%) of them reported watching TV while eating and less than one third (29%) of them were smokers.

|

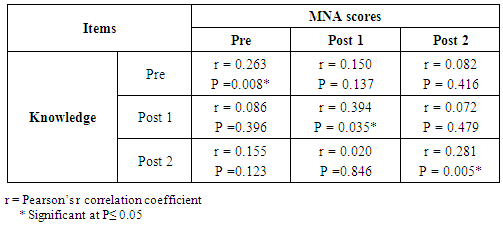

| Figure 1. Food choice and preparation among the studied elderly |

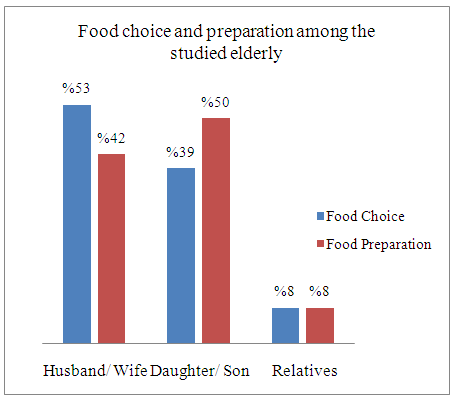

| Figure 2. Source of knowledge about healthy nutrition among the studied elderly |

|

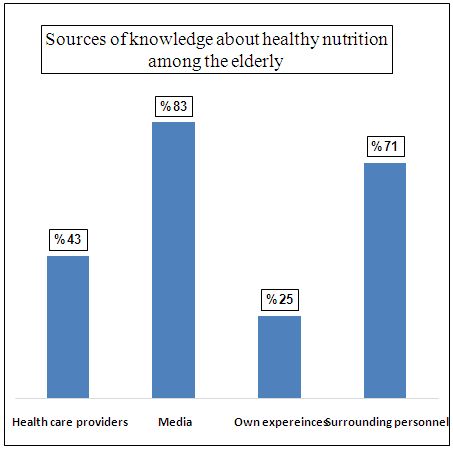

| Figure 3. Distribution of the studied elderly according to their total knowledge score level about healthy nutrition before and after nutrition educational program |

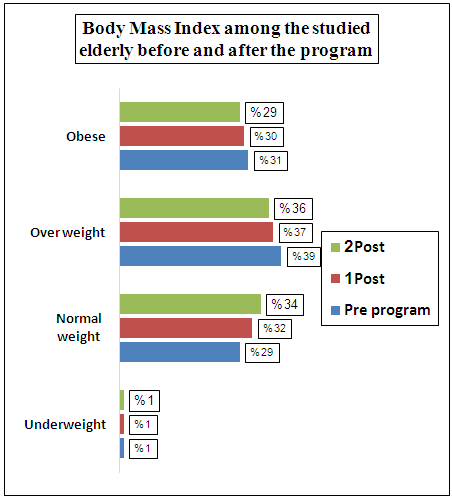

| Figure 4. Distribution of the studied elderly according to their BMI before and after nutrition educational program |

|

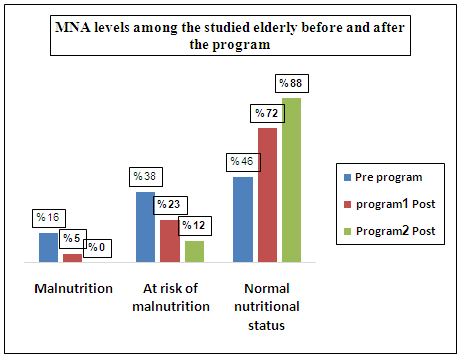

| Figure 5. Distribution of the studied elderly according t their Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) total scores before and after nutrition educational program |

|

4. Discussion

- Successful aging is a multidimensional concept that is characterized by avoidance of disease and disability, maintenance of high levels of physical and cognitive functioning, and sustained engagement in social and productive activities [23, 24]. Good nutrition throughout the lifespan supports healthy aging. Nutrition has multidimensional effects on cognition, mood, functional ability, and survival. Good nutritional status and diet quality prevent cognitive decline, loss of muscle mass, frailty, and loss of functional ability. Nutrition is also important in preservation of normal immune functioning [25, 26].Older people are more vulnerable to inadequate nutrition than younger adults and have a higher risk of nutrient deficiencies. The causes of nutritional deficiency in older people are likely to be multifactorial and reflect physical and physiological impairments, as well as psychosocial influences [27, 28]. Aging is associated with distinct changes in body composition. The most notable are decreases in intracellular fluid and lean body mass and an increase in the amount of and change in the distribution of fat stores. In clinical terms, these changes predispose older people to dehydration, reduced basal metabolism, falls and injury, and central weight gain. Evidence suggests that nutrition plays a role in the progression and attenuation of these changes [29, 30].Results of the current study portrays that less than one fifth of the studied elderly had malnutrition and more than one third of them are at risk of developing it. Furthermore, the body mass index of the studied elderly reflects that only 29% of them had normal weight. These results come in line with that of Kalyan et al (2015) [31] who found that 40% of the elderly had malnutrition and 36.5% of them were at risk. Similar results were provided by Tyagi et al (2010) [32] and El Kady et al (2011) [29] who found that (18% and 12% respectively) of their patients suffered from malnutrition.During aging, generalized decline in function involves all organs. As part of the normal aging process, many changes occur in the human body that may negatively influence intake, absorption or utilization of nutrients. Not all organs age in the same manner or at the same rate. With aging total body water decreases by 20% and body fat increases, which results in a decrease of metabolic rate that could lead to decreased oral intake. These changes can make it more difficult for the elderly to meet their commended daily nutritional allowance [28, 33]. This was reflected in the present study finding as age of the elderly was significantly correlated with the mini nutritional assessment scores. In agreement, Grace et al (2009) [34] and Johansson et al (2009) [35] reported that the higher the age of the person, the greater the risk for nutritional disorders especially malnutrition.It has been anticipated that, the limited financial resources will hinder any person from having healthful life style including proper nutrition, seeking medical help, getting the expensive treatment and costly nutritional deficiencies management activities or performing follow up. Hence, scarce economic resources limit the availability of access to food. Elderly people often have to decide what foods to give priority to purchase, with an increased risk of having a non- balanced diet in terms of macro and micronutrients especially foods such as vegetables and fruits that are naturally rich in nutrients such as vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, may be too expensive and may be, for this reason, excluded from the diet. It is likely that economic hardship can lead to the use of more energy- dense foods, that are less expensive, but with a lower nutritional quality [11, 36]. This could explain the findings of the present study since income sufficiency was significantly correlated with nutritional status of the elderly. Similarly, Bouis et al (2011) [37] and Ferdous et al (2010) [38] reported that the malnutrition and nutritional deficiencies were more encountered among the poor elderly persons. Among risk factors associated with malnutrition, level of education which plays a pivotal role in nutritional status as it can affect the ability to make reliable and aware food choices [13, 17].Considering the elderly’s education, the present study findings claimed that their level education had a significant effect on the nutritional status. In agreement, Donini et al (2013) [39] and Wilma et al (2015) [40] mentioned that the majority of elder patients presented with nutritional inadequacies and malnutrition were of lower educational levels. This might be justified that lower level of education and limited literacy hindering elder people from access to proper nutrition related information.Aging is accompanied by an increased likelihood of suffering from one or more chronic diseases such as respiratory disease, arthritis, stroke, depression and dementia. These conditions may affect appetite, functional ability or ability to swallow, all leading to altered food intake and impairment of nutritional status. Medications used in the treatment of chronic illness can also have a detrimental effect on nutritional status through loss of appetite, nausea, diarrhea, reduced gastrointestinal motility and dry mouth [27, 40]. This could explain the results of the present study where presence of chronic illnesses has a significant impact on the elderly nutritional status, which come in line with the findings reported by Heuberger et al (2011) [41] and Ortolani et al (2013) [42] on studying polypharmacy among elderly patients and it deleterious effects on the nutritional status.Increasing age appears to be associated with a steady deterioration of oral health. Changes in the oral cavity, such as loss of teeth, ill-fitting dentures, decreased saliva production and gingivitis, can profoundly affect the ability of older people to chew and or swallow, with subsequent avoidance of many foods. As a consequence of these problems, older people might alter their food intake because of teething problems [2, 3, 35]. The results of the present study found a significant relation between teething problems and nutritional status, which come in accordance with those of Johansson et al (2009) [8] and Power et al (2014) [43] who reported that the poorer oral health, Thegreaterburden on nutritional status of the elderly patients.The benefits of regular exercise for older adults are well documented and include improved cardiopulmonary function, lowered blood pressure, increased confidence in the ability to perform daily tasks, and a heightened energy level. Regular physical exercise can provide older adults with added physiological reserves by reducing the risk factors of chronic diseases and slowing down the progress of frailty [2, 3]. The results of the current study revealed a significant correlation between practicing exercise and nutritional status among elderly. The same picture was portrayed by the results of Grace et al (2009) [34] and Kim et al (2012) [44] who reported beneficial effects of exercise intervention on the nutritional status of the elderly. These findings led to the suggestion to apply exercises program to induce dietary behavioral modification and consequently controlling nutritional defects among elderly.There are several psychosocial reasons contribute to the development of malnutrition among elderly including loneliness, social isolation, depression, and change in living environment. All these factors can profoundly influence nutritional practices among elderly and have an impact on appetite and food choices and intake, and increase the risk for malnutrition [27, 31]. The findings of the current study showed that food choices and preparation had significant effect on the nutritional status of the elderly which come in accordance with the results of Alexander et al 2010 [33] and Turconi (2011) [44].No doubt that knowledge about proper nutrition will determine the quality of food and the nutritional status of any human being especially among high risk groups such as elderly. This knowledge is the first step that helps to maintain and preserve health. So, good knowledge regarding nutrition is required. Therefore, physicians, nurses and other health care providers should provide them with comprehensive information about proper nutrition, which in turn help to shape positive attitude towards healthy proper nutrition and improve their practices [27, 33]. The present study demonstrated a deficit in the knowledge of the elderly regarding proper nutrition as around half of them had poor knowledge level. Similar findings were reported by Mohamed et al (2013) [46] and Asyura et al (2009 [36] who found that more than half of the subjects had poor or very un-satisfactory knowledge.It has been recognized that malnutrition is a multi-factorial problem, it can result in deleterious consequences. Nutritional care is an important mean for preventing deterioration of nutritional status in elderly. Health care professional must identify people in risk and administer high quality nutritional care interventions, which requires proper assessment of the nutritional status and intervene accordingly. Nutrition education and counseling are among the strategies applied in nutritional care of elderly [24, 35, 36].Previous researches showed the efficacy of nutritional education on the elderly’s knowledge and overall nutritional status of them. Kim B et al (2012) [47] reported that a positive effect of nutritional education on dietary knowledge, behaviors and practices. Furthermore, Mohamed et al (2013) [46] and Iranagh et al (2018) [48] who found a significant improvement of the subjects mean nutritional knowledge score after a nutritional education program as well as their dietary practices. In agreement, the implementation of the educational program of the current study led to significant increase in the elderly knowledge in the immediate assessment as well as in the follow up evaluation. Additionally, the elderly scores on mini nutritional assessment showed improvement after the application of the program as reflected in increase the number of those elderly with normal nutritional status.In further confirmation of the positive effect of the educational program on the knowledge of the elderly in the current study, a significant correlation was found between the elderly’s knowledge and their Mini Nutritional Assessment scores. This finding portrays the importance of nutritional knowledge as a key element to promoting healthy dietary habits as well as promoting general health. The association between nutritional knowledge and diet-related health outcomes has been studied in various studies which report that individuals with limited health knowledge are more vulnerable to unhealthy life style and nutritional problems [33, 46, 49].Moreover, dietary informational resources are important factors for promoting nutrition knowledge among elderly people [50, 51]. In Aihara et al (2011) [52] study, the majority of the study participants received diet and nutritional information from television. Similar findings were found in the present study where mass media was the main source of health-related knowledge among the elderly. Health information from the mass media is important because it is reachable and trustable among a large sector of the population. So, the role of mass median creating health consciousness should be emphasized.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Based upon the findings of the current study it could be concluded that malnutrition is a serious problem among elderly. More than one fifth of the studied elderly were malnourished and more than one third of them were at risk. It is apparent from this study that poor nutritional knowledge was experienced by around half of the elderly. On the other hand, a significant improvement in the nutritional knowledge and in the nutritional status as evident by the scores of min nutritional assessment was found after the implementation of a nutritional educational program. Furthermore, it is highlighted by the present study that there was a significant association between elderly‘s age, level of education, income, presence of health and teething problem, food choice and food preparation and mini nutritional assessment scores. From the results of the current study it could be recommended that perform routine nutritional screening of elderly on regular base to identify those at risk and intervene accordingly. Work collaboratively with the patient to develop an education plan and set goals that aim to optimize nutritional status are recommended. Empower elderly through education necessitates the incorporation of interactive teaching strategies and to address their physical, psychological and social needs. Involve elderly in the management of their nutritional problems, foster independence and self-management behaviour. The health education provided must be individual-centered, culturally sensitive, and appropriate for the elderly’s age, socioeconomic status, and level of education. Orient the elderly to community resources that may include accessible and convenient areas for exercise, affordable fresh food, and access to local pharmacists. In addition, telephonic and web-based interventions are showing promise as tools to enhance health knowledge among elderly. Lifestyle modification interventions that include healthy eating and exercise have been proven effective for elderly with malnutrition problems.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML