-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2018; 8(3): 51-56

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20180803.02

Theory of Reflective Practice in Nursing

Gemma Domingo Galutira

School of Nursing, Saint Louis University, Baguio City, Philippines

Correspondence to: Gemma Domingo Galutira, School of Nursing, Saint Louis University, Baguio City, Philippines.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

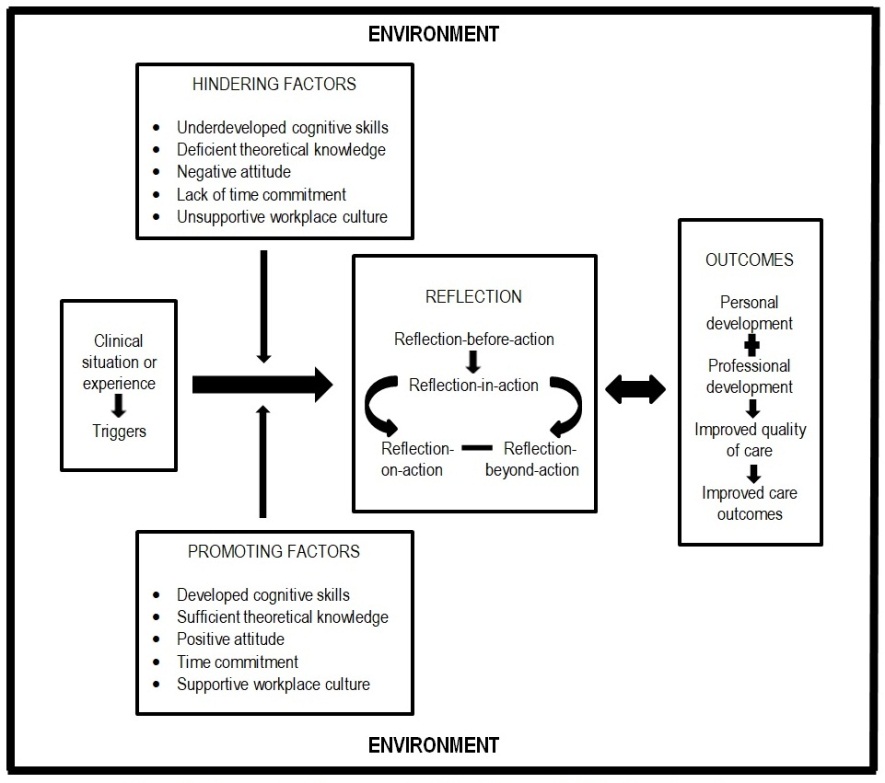

This article explicates the author’s Theory of Reflective Practice in Nursing and its philosophical underpinnings. The Theory of Reflective Practice in Nursing is a middle-range theory. It mainly proposes that nurses must practice reflection-before-action, reflection-in-action, reflection-on-action, and reflection-beyond-action to advance nursing practice. Reflective practice can impact positive outcomes such as personal and professional development, improved quality of care, and improved care outcomes. Moreover, the theory posits that the environment provides the context of the concepts of reflective practice. The environment can nurture or inhibit effective reflective practice. The theory has strong interpretive and phenomenological roots thus it exemplifies a postmodernist perspective. Reflection is a way of knowing in nursing that typifies the subjective, explicatory, and contextual form of knowledge that emerges from nurses’ practice experiences.

Keywords: Reflective practice, Reflection, Nursing theory

Cite this paper: Gemma Domingo Galutira, Theory of Reflective Practice in Nursing, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 8 No. 3, 2018, pp. 51-56. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20180803.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Reflection has been considered as a significant concept of nursing for many years. Based on the growing evidence found in the nursing literature, reflection remains to be an interesting concept because of its influence on education and practice worldwide. Nursing education has welcomed the idea of reflection as a valuable tool to assist nursing students in learning from practice (Jootun & McGarry, 2014). Likewise, reflection is considered instrumental in helping nurses provide optimum care to patients (Caldwell & Grobbel, 2013).Dewey introduced the concept of reflection in 1933 (Ruth-Sahd, 2003) and it broadened over time. Based on Dewey’s (1933) work, Schon (1991) identified two types of reflection: reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action (as cited in Armstrong & Asselin, 2017). Expanding the two types of reflection identified by Schon (1991), Edwards (2017) advanced two additional dimensions: reflection-before-action and reflection-beyond-action. Putting the four types together, Edwards (2017) proposed a modified chronology of reflection: reflection-before-action, reflection-in-action, reflection-on-action, and reflection-beyond-action.Reflective practice is considered as a crucial part of professional practice (Asselin, Schwartz-Barcott, & Osterman, 2012) because it promotes continuous development (Gustafsson & Fagerberg, 2004). Reflection as a process of discovering alternative types of nursing knowledge, including empirical, aesthetic, personal, and ethical forms (Berman, Snyder, Kozier, & Erb, 2008) leads to change in practice (Asselin et al., 2012). Indeed, reflection helped uplift the status of nursing as a profession (Edwards, 2017). The value attached to reflection served as an impetus for the development of the theory of reflective practice. This paper aims to explicate the author’s Theory of Reflective Practice in Nursing including its philosophical underpinnings.

2. Philosophical Underpinnings of the Theory

- The theory was developed based on the author’s philosophy that life situations and experiences provide a significant means for persons to learn. Persons are privileged to learn from and find meaning in their lived experiences throughout life. One way for persons to learn is through the reflection of their life situations and experiences. Persons subsequently grow and develop to become better individuals who can make a difference in their lives and of others’. The author’s philosophy attunes to the interpretive phenomenological perspective. Phenomenology focuses on lived experiences and personal perceptions (Finlay, 2008; Munhall, 2012). Based on Heidegger’s (1962, as cited in Alligood & Tomey, 2010) phenomenological description, persons as self-interpreting beings are defined by concerns, practices, and life experiences. Persons’ cognitive reflective abilities depend on embodied knowing (Benner & Wrubel, 1989 as cited in Alligood & Tomey, 2010), that is, persons learn things by being in situations (Alligood & Tomey, 2010). Persons who are continually situated engage meaningfully in the context of their situations (Alligood & Tomey, 2010) and find meaning in their transaction with the situations (Munhall, 2012). The persons’ interpretation of experiences from their unique perceptions is critical and the reality to be concerned with (Munhall, 2012).Furthermore, the author’s philosophy conforms to a constructivist perspective which is also grounded on the philosophy of phenomenology. According to a constructivist perspective, persons actively create knowledge and meaning through an interaction between their ideas and their experiences. Persons construct their overall interpretations from their perceptions, opinions, and experiences of situations and consequently build their knowledge base (Hutton, 2009). Persons discover practical knowledge through their involvement in situations (Heidegger 1962, as cited in Alligood & Tomey, 2010).Fittingly, reflection is an epistemology of practice (Fragkos, 2016) attuned to postmodernism which stresses that knowledge or truth is multifaceted (Holloway & Galvin, 2017) and multiple voices are valuable (Munhall, 2012). Reflective practice privileges knowledge arising from interpretations of experiences in practice situations (Mantzoukas & Watkinson, 2008). Experience in nursing practice is a reliable source for knowledge claims (Avis & Freshwater, 2006). Categorically, reflection exemplifies the subjective, explicatory, and contextual form of knowledge (Mantzoukas & Watkinson, 2008) derived by nurses from their practice experiences. Reflective practice also privileges knowledge that is systematically created by conscious analytical methods similar in various ways to those of science and research (Mantzoukas & Watkinson, 2008). Reflective practice allows practitioners to develop nursing theories and generate nursing knowledge thereby influence practice (Emden, 1991; Reid, 1993 as cited in Greenwood, 1998; Peterson, Davies, Rashotte, Salvador, & Trepanier, 2012 as cited in Goulet, Larue, & Alderson, 2016).

3. Description of the Theory

- The Theory of Reflective Practice in Nursing is a middle-range theory. This level of theory has limited scope and number of variables but testable (Walker & Avant, 2005). The theory posits that reflective practice must entail reflection-before-action, reflection-in-action, reflection-on-action, and reflection-beyond-action to optimize the potential of reflection in advancing nursing practice. The assumptions, key concepts, propositions, conceptual framework, and metaparadigm concepts are presented to provide a comprehensive description of the theory.Assumptions of the TheoryThe author’s assumptions shaped her theory. The assumptions include: 1. Persons consist of multiple dimensions which include physical, cognitive, emotional, social, and spiritual.2. Persons are integrated holistic beings. 3. The environment affects persons, processes, and results. 4. Persons incessantly encounter events that affect their multiple dimensions. 5. Persons can learn from and find meaning in their lived experiences. 6. Learning is a lifelong process. 7. Reflection is one of the ways by which persons learn.Key Concepts of the TheoryKey concepts comprise the Theory of Reflective Practice in Nursing. The key concepts are reflection, clinical situation or experience, promoting factors, hindering factors, and outcomes.Reflection involves a detailed exploration of a clinical situation or experience which includes an analysis of personal feelings, thoughts, and actions or behaviors. It entails cognitive activities such as description, critical analysis, evaluation, and planning. Reflection is also a way of learning from a clinical situation or experience. It is a means by which feelings, perspectives and/or behaviors change. Moreover, reflection is an active and dynamic process. It involves reflection-before-action, reflection-in-action, reflection-on-action, and reflection-beyond-action. Lastly, reflection is a cyclic process. New understanding, thought or perspective about a clinical situation or experience is considered in planning for future learning or in taking future actions.Clinical situation or experience refers to an incident which involves the individual client, family, group, or community and the nurse. It presents to the nurse a chance to learn and/ or demands a solution to a problem in clinical practice. In a clinical situation, both the client and the nurse demonstrate certain actions or behaviors that evoke thoughts and/or feelings of the nurse that serve as triggers. Triggers refer to the nurses’ negative or positive thoughts and/or feelings associated with the clinical situation or experience that give rise to reflection. Promoting factors refer to the elements which encourage nurses’ reflection. These include developed cognitive skills, sufficient theoretical knowledge, positive attitudes, time commitment, and supportive workplace culture. Hindering factors refer to the elements that impede nurses’ reflection. These include underdeveloped cognitive skills, deficient theoretical knowledge, negative attitudes, lack of time commitment, and unsupportive workplace culture.Outcomes refer to the favorable results of reflection. These include personal development, professional development, improved quality of care, and improved care outcomes.Propositions of the TheoryThe propositions explain the relationships that exist among the concepts of the theory. The propositions include: 1. A clinical situation or experience evokes nurses’ thoughts and/or feelings that serve as triggers of reflection.2. Nurses’ developed cognitive skills, sufficient theoretical knowledge, positive attitudes, time commitment, and supportive workplace culture promote reflection. 3. Nurses’ underdeveloped cognitive skills, deficient theoretical knowledge, negative attitudes, lack of time commitment and unsupportive workplace culture hinder reflection. 4. Reflection occurs before, during, and after a clinical situation or experience. 5. Reflection brings about nurses’ personal and professional development. 6. Nurses’ personal and professional development through reflection results to improved quality of care provided to clients. 7. Reflection leads to improved care outcomes through nurses’ provision of better quality of care to clients. 8. The attainment of positive outcomes encourages nurses to integrate reflection into their day-to-day clinical practice.9. The environment provides the context of the concepts of reflective practice.Figure 1 shows the existing relationships between the concepts of the theory. The clinical situation or experience encountered by the nurse evokes negative or positive thoughts and/or feelings that serve as triggers. The negative feelings that often trigger reflection include guilt, anger, sadness, frustration, resentment, and hatred (Boyd & Fales, 1983 as cited in Johns, 2013). Moreover, nurses tend to reflect when they think that they have delivered poor care (Gustafsson & Fagerberg, 2004). Nurses may also reflect when they feel satisfied with their clinical performance and/or think that they have provided excellent client care.

| Figure 1. Conceptual Framework of the Theory of Reflective Practice in Nursing |

4. Conclusions

- The theory of Reflective Practice in Nursing is a middle-range theory which has strong interpretive and phenomenological philosophical roots. The theory exemplifies a postmodernist perspective. Reflection is an epistemology of practice that represents the subjective, explicatory, and contextual form of knowledge that emerges from nurses’ practice experiences. Reflective practice allows practitioners to develop nursing theories and generate nursing knowledge thereby influence practice. Reflective practice ultimately advances professional nursing practice.Testing of this theory is imperative. Research studies using qualitative and quantitative approaches are recommended. Tools to measure the concepts particularly the outcomes of reflection must be developed to establish substantial scientific evidence regarding the relevance of this theory in nursing practice. The propositions of the theory can provide direction for research studies aimed at theoretical testing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The author would like to express her deepest gratitude to Dr. Annabelle R. Borromeo and Dr. Ludivina C. Ramos for their guidance in this academic endeavor.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML