-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2018; 8(1): 13-16

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20180801.03

A Literature Review: The Role of Bar Coding and Smart Pumps in Patient Safety at Intensive Care Unit

Hanan Mohammed Mohammed

Assistant Professor of Medical-Surgical Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Ain Shams University, Egypt

Correspondence to: Hanan Mohammed Mohammed, Assistant Professor of Medical-Surgical Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Ain Shams University, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Medication safety in hospitals depends on the successful execution of a complex system of scores of individual tasks that can be categorized into five stages: ordering or prescribing, preparing, dispensing, transcribing, and monitoring the patient's response. Many of these tasks lend themselves to technologic tools. Over the past 20 years, technology has played an increasingly larger role toward achieving the five rights of medication safety: getting the right dose of the right drug to the right patient using the right route and at the right time. While several of these technologies may incur significant upfront and maintenance costs, the net impact over time may be reduced overall institutional costs and improvements in work efficiency. Examples of technologic tools commonly seen in many hospitals today include computerized provider order entry (CPOE) with decision support and automatic dispensing carts, also known as medication dispensing robots. While outside the scope of this Perspective, it is important to emphasize that many non-technologic interventions, such as clinical pharmacists on physician rounds, can be equally effective in improving medication safety.

Keywords: Bare Coding, Smart Pumps, Safety, Intensive Care Unit

Cite this paper: Hanan Mohammed Mohammed, A Literature Review: The Role of Bar Coding and Smart Pumps in Patient Safety at Intensive Care Unit, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2018, pp. 13-16. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20180801.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Research has shown that most medication errors are made by providers during the prescribing stage. These errors are often intercepted by pharmacists, nurses, or colleagues, or by the use of CPOE. Dispensing errors are primarily committed by pharmacy staff, though many are intercepted by nurses prior to administration. In a single-center study, undetected pharmacy dispensing committed by pharmacy technicians and not intercepted by hospital pharmacists occurred in 0.75% of doses. This rate translates to over 1200 errors per year in a 500-bed hospital. Since nurses often act as the last line of defense in the medication use process, administration errors at the point of care often lack additional safety nets and as such are infrequently caught [1].Smart intravenous (IV) infusion pumps have been developed to mitigate errors that occur at the administration stage. These errors have the greatest potential for life-threatening harm because of the dangers of 10- to 100-fold errors in IV medication doses, especially with high-risk medications such as insulin, heparin, propofol, and vasoactive medications. Smart IV infusion pumps have drug libraries with standardized concentrations for commonly used drugs, which allow them to provide point-of-care decision support feedback for excessively high or low rates and doses (Figure 1). These devices may be programmed to provide "soft" alert feedback, which allows overrides, and "hard" alerts that cannot be overridden. For example, a pump that is programmed with an uncommonly high insulin infusion rate of 20 units per hour may trigger an alert requiring the nurse to confirm this dosage before permitting an override, while an alert for a rate of 200 units per hour should be a "hard" stop that cannot be overridden. Drug libraries may be unit specific, with unique rules for individual clinical areas such as pediatrics, obstetrics, and critical care. Additionally, the use of certain IV medications may be prohibited outside certain clinical areas (such as prohibiting the use of neuromuscular blocking agents outside of intensive care units [ICUs] and operating room settings) [2].

| Figure 1. The smart pump is programmed by using the drug library, which determines if the medication dose and rate are within predefined acceptable limits |

2. From “Dumb” to “Smart” Pumps

- The first programmable IV infusion pumps came into use more than 40 years ago. Being able to program a specific rate and volume made modern infusion therapy possible; but these “dumb” pumps could accept any infusion rate from 0.1 to 999 mL/hr or higher. Programming 54 instead of 5.4, 800 instead of 8, or entering the volume as the rate could each deliver a fatal dose. Compared to medications delivered via other routes, IV medication errors are twice as likely to cause patient harm. For the next three decades, the potential for pump mis-programming and other errors remained a critical issue [6].In the late 1990s a technological breakthrough — electronically erasable programmable read-only memory (EEPROM)—made it possible to develop “smart” pumps with safety software that could be customized to a hospital’s specific care areas and patient types. The customized software generated an alert or prevented infusion altogether if pump programming exceeded the hospital-established limits. The widespread implementation of such pumps significantly improved IV medication safety. In more than 10 years since their introduction, smart pumps have [7]:Ÿ Fostered development of drug dose limits.Ÿ Promoted standardization of concentration and dosing units.Ÿ Allowed hospitals to configure pumps to match applications.Ÿ Provided a “treasure trove” of infusion data.Ÿ Documented many “good catches” of prevented programming errors.Ÿ Uncovered high degree of variation in infusion practices.Ÿ Identified human factors issues/opportunities for manufacturers.Ÿ Promoted wireless connectivity/server applications.While smart infusion pumps alone may prevent pump programming errors, they cannot prevent giving the wrong drug or the wrong concentration, or giving the drug to the wrong patient. In a large multicenter study that included 24 hospitals, Barker found an administration error rate of 11%, excluding wrong-time errors [8]. An observational British study found IV administration errors in 42% of doses; IV boluses that were infused at an excessive rate were especially common. Recent tragic events in two leading hospitals underscore prevailing systematic deficiencies in the medication system. In both cases, errors led to the wrong concentration of IV heparin being administered, resulting in 1000-fold overdoses. These errors were responsible for the deaths of three newborn infants at Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis in 2006 and placed the premature twins of actor Dennis Quaid at life-threatening risk at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in 2007. These overdoses most often occur in settings where heparin vials of different concentrations are stocked in patient care areas, allowing them to bypass pharmacist checks [9]. Bar-coded medication administration (BCMA) coupled with an electronic medication administration record (eMAR) targets errors that occur at the drug dispensing, transcription, and administration stages. BCMA provides point-of-care verification of the correct patient and medication. When electronically linked to CPOE, this medication system also electronically tethers the administration to the medication order. The BCMA system includes a single-unit dose bar-coded medication package that is scanned prior to dispensing from the pharmacy. Prior to administration, the medication package is scanned by the nurse using a handheld barcode scanning device to confirm the right medication (Figure 2) [5].

| Figure 2. Infusion Auto-Pump Programming Using Barcode Scanning |

| Figure 3. Barcoded Medication Administration |

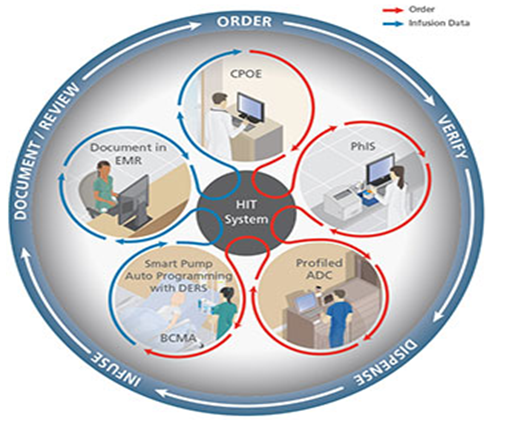

3. From “Smart” Pumps to “Intelligent” Systems

- A major limitation has been that even with connectivity, infusion pumps typically operate in insolation—not assigned to a particular patient, not aware of the intent of therapy, unaware of caregiver proximity, and unable to interact with other safety technologies. Wireless connectivity and direct communication with BCMA, the hospital information system (HIS), and other systems can overcome these shortcomings and elevate the current smart pumps to the new level of “intelligent” infusion system [13]. Fully developing and implementing such systems will take time, but the impact will be dramatic [6].The 2011 American Society of Health-System Pharmacists National Survey showed that in the intervening eight years, the vast majority of hospitals had implemented or budgeted for the foundational technologies of CPOE, BCMA, smart pumps, and electronic medical records (EMRs) (Pedersen et al., 2012). Almost a decade after Ohio Valley General Hospital’s implementation, the technologies, software applications, regulatory approvals, and multidisciplinary teams were in place in most large hospitals to implement scalable, sustainable, reliable smart pump-EMR integration for house-wide clinical use [9].

4. Possible Starting Points

- Several factors make infusion pumps an ideal starting point for interoperability: the very large number of devices in a typical hospital, the critical importance of the drugs being infused, the growing base of wirelessly connected pumps already installed, and their uniquely bidirectional information transfer, both from and to the pump. A few hospitals have already implemented closed-loop systems that integrate BCMA, smart pumps, and the electronic medical record (EMR), as described below. But other entry points are also possible. For example, one hospital might decide that interfacing the smart pump and BCMA systems is the highest priority, while another might choose to work on sending alarms directly to the patient’s clinician. An ultimate goal is to connect and monitor all infusion-related systems in a type of “air traffic control” surveillance that would automatically flag any critical, infusion-related situation that requires immediate attention [14].

| Figure 4. Fully Integrated, Closed-Loop, Medication Safety System |

5. Conclusions

- The adoption of smart infusion pump and BCMA technology is still early, with recent estimates indicating rates of hospital adoption of 44% and 23%, respectively. Nurses are considered the front line of patient defense in detecting patient deterioration and protecting patients by recovering errors caused by other clinicians. Despite this vital charge, until recently nurses had few if any safeguards between them and the patients to prevent medication administration errors. New technologies now provide tools for clinicians to enhance safety throughout the medication use process.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML