-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2018; 8(1): 8-12

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20180801.02

Nursing and Pharmacy Students’ Perception of Employability Skills in a Selected University in Kingston, Jamaica

Andrea Pusey-Murray 1, Andrea Wilkins Daly 2, Deveree Stewart 1

1Caribbean School of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, University of Technology, Jamaica

2School of Pharmacy, College of Health Sciences, University of Technology, Jamaica

Correspondence to: Andrea Pusey-Murray , Caribbean School of Nursing, College of Health Sciences, University of Technology, Jamaica.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

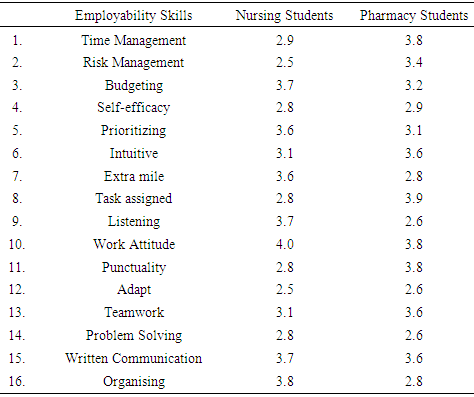

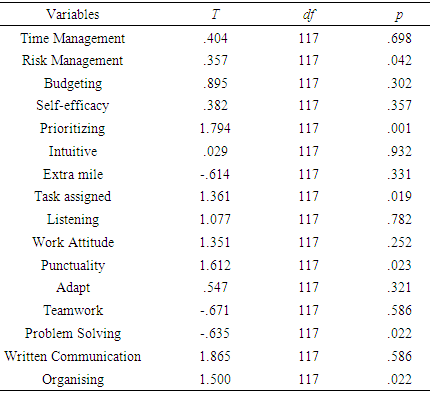

Objective: This paper presents the perceptions of employability skills of undergraduates at a university in Kingston, Jamaica. Three research questions guided the study. This descriptive survey aimed to determine the extent to which undergraduate students valued employability skills. Method: The study utilized a cross-sectional survey research design in order to use quantitative data collection and data participated in this study. A total of 160 students were selected using the stratified random sampling method. Data was analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19. Results: Overall, the highest employability skill with the highest mean among the Nursing students were work attitude (4.0) and task assigned (3.9) among the Pharmacy students. On the other the hand, adapt (2.6), problem-solving (2.6) and organizing (2.8) among the pharmacy students while for the nursing students adapt (2.5), risk-management (2.5) and time management (2.5). For both groups the following employability skills were significant, prioritizing t= 1.794, df =117, p= .001, task assigned t= 1.361, df = 117, p=.019, problem-solving t= -.635, df = 117, p=.022, organizing t =1.500, df = 117, p=.022, punctuality t =1.612, df = 117, p = .023 and risk management t =.357, df = 117, p=.042. Conclusion: This study has recognized challenges that need to be addressed in order for the students to be marketable. Emphasis on employability skills cannot be left until the students graduate; it is of great importance that they be developed throughout their course of study.

Keywords: Employability skills, Nursing, Pharmacy, Undergraduate

Cite this paper: Andrea Pusey-Murray , Andrea Wilkins Daly , Deveree Stewart , Nursing and Pharmacy Students’ Perception of Employability Skills in a Selected University in Kingston, Jamaica, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 8 No. 1, 2018, pp. 8-12. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20180801.02.

1. Introduction

- Today’s job responsibilities and competency level required from individuals are continuously changing and the pace of this change constantly contests the improvement of didactic programs [1]. One such contest is to conclude the appropriate balance of technical, employability, and academic skills for workplace education. The current business environment internationally has recognized and strongly emphasizes that the importance of education for employability should focus on the development of key skills and work experience. Although there may be several definitions of ‘employability,’ Yorke [2] has defined employability as “a set of achievements — skills, understandings and personal attributes — that make graduates more likely to gain employment and be successful in their chosen occupations, which benefits themselves, the workforce, the community and the economy” [3]. With regards to the Jamaican Government as well as higher education institutions and industries here in Jamaica, employability is a critical issue. Due to the continuous expansion in higher education plus the recent economic downturn, there is intense competition for jobs in the graduate employment market [4]. Thus, it is becoming increasingly important for graduates to be able to apply the knowledge and skills learned in higher education institutions to the workforce [5]. Additionally, this is further elaborated by Evers and colleagues who stated that there is a need for a fundamental shift toward an emphasis on general skills in education [6]. Nevertheless, it has been hinted that entry-level graduates are not entirely equipped with the general, transferable skills necessary for employment and thus are unprepared to enter the workforce [1, 5, 7-9]. Therefore, the development of undergraduates from a mere theoretical background to the combination and balance of both theory and practice is an essential modern-day need, hence for that reason the practice will enhance the employability of graduates. Increasing participation of undergraduates in the training process is now more than ever, very important in order to understand the undergraduates’ trainee future skills development areas [10]. This will therefore assist undergraduate students going into the world of work to be competent as well as equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge base combined with practical competence in order to meet the expectations of their future of present employer.The interest of employers, both locally and internationally, on improved employability skills of university graduates has been well documented by many studies. Breiter and his colleague found leadership competency to be the most critical competency, deserving a high level of attention in management for the 21st century [11]. Employees must be able to explore career possibilities from a variety of disciplines and viewpoints thus being able to be aligned with the direction of the new wave in business, which will demand a unique set of skills to successfully compete in this environment [1]. In addition to leadership skills, the ability to supervise, coordinate, manage conflict, have a clear vision, be creative, innovate, adapt to change, motivate, and lifelong learner are some other employability skills important to motivate [6, 12, 13]. As a result, important questions have arisen concerning the university graduates level of competence in performing essential employability skills. Do university education programs adequately prepare their students to be society-ready? One of the key reasons why many students invest in university education is to improve their employment prospects. However, whilst achievement of good academic qualifications is highly valued, it no longer appears sufficient to secure employment [2]. If not, how can the program be improved or changed to meet the demands of the employers? As such, a study of the university students’ perception on the importance of employability skills is of utmost importance in generating insights and assisting universities in developing their courses of study to develop such areas, which is an issue of serious concern.Employability skills are essential skills often viewed as a company’s most important raw material [14]. Additionally, it is not clear that enough is being done to promote these employability skills amongst the students graduating from tertiary institutions. The information gathered could be used to create awareness amongst curriculum developers, and for the universities to be more involved in apprenticeship programs. It is also hoped that the strategies recommended will not only inform interested party, but will also serve as a catalyst that will engender meaningful education reform in Jamaica. Ultimately, it is the desired outcome of this study to evoke further investigations into the subject of employability skills in Jamaica.

2. Method

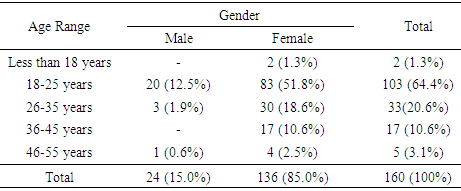

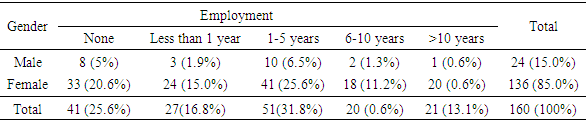

- A cross-sectional survey research design was used which allowed for the utilizing of quantitative data collection and data analysis, “in a cross-sectional survey research design, a researcher collects data at one point in time” [15].Students who were used in this study were from the main campus and were selected using the stratified random proportionate method. The sample size was (n=160). In selecting a representative sample for the study, a sampling frame was obtained from the five nursing programmes (Registered General Nursing, Critical Care Nursing, Direct Entry and Post Basic Midwifery and Nurse Anaesthesia Course) and two pharmacy programmes (Bachelor of Pharmacy and Post Diploma in Pharmacy). The obtained sampling frames contained the names and gender of the students in the respective of the programmes.Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Only the undergraduate and graduate full-time students in the program who have at least completed the first semester year of their first academic year were included in the study. Students in the franchised programmes and those in the Western region of the island were excluded from the sampling frame.This meant that those who have not completed the first semester (full-time) undergraduate students were excluded. The researchers entered the data into the SPSS program (version 20). Finally, descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) was used to compute the demographic data, while t test was used to analyze items in the questionnaire, which addressed the research questions. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committees of the University of Technology, Jamaica.FindingsGender by age-range. Of the 160 participants in the study 24 (15.0%) were males, while 136 (85.0%) were females. As shown in Table 1, 103 (64.4%) of the respondents were between the ages of 18 and 25 years. See Table 1 for the detailed cross-tabulation of gender and age range of the respondents.

|

|

|

|

3. Discussion

- There is, implicit within this the need for graduates (and undergraduates seeking placements etc.) to be able to demonstrate their attainment of various skills and competencies, something that our own observations and those of others has shown to be a problem [16]. There is the need therefore for an integrated approach allowing students to successful attainment in their employability skills, through assessment and feedback and completion of some form of professional development review, or record of achievement as well as portfolios. Changes to current assessment and feedback procedures and types have been designed to address the issues identified around students being able to demonstrate their achievements in a language accessible and recognized by employers [17]. The strategy is one based around the concept of “Employability in the core curriculum” for adjustment to assessment and feedback procedures [2]. Oral communication, teamwork, self-management, problem solving and leadership are all important [3].Team work has been an important part of university work and assessment for many years in forensic science but it is often assessed indirectly through assessment of the end product of the group work. Group work in key modules now requires that students complete peer and self-assessment tasks and produce reflective statements throughout the group exercise and process is assessed as part of the overall summative assessment of the exercise.Although team work was quite important for both groups with a mean of over 3; it was lower among the nursing students. This is a very important skill that should be fostered between the students. Some may limit their development of some of the employability skills especially teamwork if they are not encouraged to take on project roles which are outside their area of comfort. This issue can be mitigated to some extent by lecturers requiring all team members to undertaken certain roles such as peer teaching, rubric for each group members contribution and rotating the role of team leaders and selecting and closely monitoring students projects.This emphasizes that employability skill development cannot be left until students graduate, but instead should be developed throughout their degree programme. More specifically, we believe that every subject in an undergraduate or graduate programme should take on the responsibility of developing one or more employability skills. In this way, by the time students are eligible to graduate they will have a sound skill-base on which to integrate the full range of employability skills within the one experience.Employers today are expecting that the University will equip the students with the requisite employability skills, so that they can make a direct input to the institution when employed. As it relates to some employers, the degree subject studied is not as important as the graduates’ ability to handle complex information and communicate it effectively [17]. Problem solving and the ability to adapt were ranked low in both groups 2.8 for nursing students and 2.6 for pharmacy students. This is of course worrying when teamwork is tied closely with problem solving and employers are looking for this quality in graduates. It is presently the high demand by graduate recruiters to seek students who possess a variety of other skills, personal and intellectual attributes rather than specialized subject knowledge. Although employers require potential employees to have problem solving capabilities it is recognized that there is no clear way of observing this skill and as such are dependent on third party certification to say whether the potential employee is suitable for the required job [18]. Development and fostering strong links between universities and business entities can create opportunities to integrate and develop employability skills in undergraduates.Written communication and listening which are essential to communication were important to students. The evidence was seen with mean values above 3.5. Employers are looking for employees with who are able to communicate effectively. This communication begins in lectures. One way of doing so is by way of formative feedback. In doing this, students can be orientated to the expectations of the workforce, make provisions for clarification of misconceptions and provides support during the learning process [19, 20]. The aim will be to make the assessment as authentic as possible to be able to meet the needs of students by contributing to the content and context of the assessment task. Fostering a culture of deep learning allow students to develop the skills of time management, intuitiveness, prioritizing, self efficacy and the remaining attributes that were identified earlier in this article. Deep learning is achieved through high quality teaching where the cognitive processes of students are challenged to meet the intended learning outcomes [21]. Deep learning students encourage and promote reasoning. When students are provided with information in ways for them to interpret, they will be able to reproduce this information and apply. Students will then be able apply what they have learnt with what they already know and have experienced. At the same time this can become a challenge for lecturers in some faculties who faced with the dilemma of trying to deliver lots of information in a very short time, large classroom size and the way in which the information is being delivered. Overcoming this challenge can be tackled by making teaching creative and finding innovative ways to engage each student.The adaptation of whole brain learning will accommodate students’ diverse thinking preferences, and to develop areas of lesser preferred modes of learning, thus contributing to the development of each student potential [22]. It also allows for exploitations of strengths, identifying and addressing student strengths, ensure enjoyment, variety and high quality learning [23]. Appreciating the way students learn is imperative, it is however recognized that a skilful performance will be of no value to students unless they are actively engaged [24]. To foster the development of employability skills with every student in mind, learning outcomes have to be formulated to meet the aims of the programme for the final qualification to be attained. They have to be developed to reflect the generic foundation skills, attributes and abilities that are unique to the programme of study.

4. Conclusions

- The study identified the employability skills needed by our graduates to enhance their preparedness for the workforce. It highlighted the importance of supporting employability skills with academic values by making unequivocal links between the curriculum and employability skills.The following recommendations are made:Ÿ Emphasis should be placed on the employability skills throughout the curriculum.Ÿ Universities to offer work-related practicum as part of a professional accreditation. This practicum would be geared towards preparing the student for employment. Ÿ Higher education institutions to provide academic staff with relevant support and resources.Ÿ Offering students self-assessment for employability skills.Ÿ Students should take responsibility in reviewing their own employability skills.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML