-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2017; 7(5): 107-110

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20170705.02

Psycho-Physiological Parameters of Nurses in Critical and Non-Critical Units

Rakesh Sharma1, Deepak Goel2, Malini Srivastav3, Renu Dhasmana4

1Faculty Nursing, College of Nursing AIIMS Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India

2Principal Consultant, Neurology Max Institute of Neuroscience, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India

3Professor in Dept. of Psychology, HIMS, Swami Rama Himalayan University, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India

4Professor in Dept. of Ophthalmology, HIMS, Swami Rama Himalayan University, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India

Correspondence to: Rakesh Sharma, Faculty Nursing, College of Nursing AIIMS Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Nurses working in critical care units are involved in numerous activities and have different roles at a time, all of which may be important for the patient but within limited working duty hours. Staff nurses are exposed to a number of stressors especially in critical units, continuously working in critical units can lead to changes in the physiological parameters of staff nurses and also can deteriorates their quality of life. Method: A comparative pilot study was carried out to find the differences in the physiological parameters and quality of life (QOL) of staff nurses posted in critical & non-critical units. Data were collected with demographic proforma, quality of life was assessed with WHOQOL-BREF, and to measure physiological parameters, a computerised stress profile test was performed on each staff nurse. Result: The mean age of staff nurse was 28.47±3.7 and all the nurses were female in critical and non-critical units. The mean heart rate and GSR were significantly higher and skin temperature was lower in critical unit staff nurses (CUSN). Whereas, score in domains of quality of life was higher in non-critical unit staff nurses (NCUSN). Conclusion: staff nurses working in critical units had higher level of physiological parameters than non-critical unit staff nurses. This indicates that the staff nurses working in critical units are more stressed and their lower QOL than non-critical unit staff nurses.

Keywords: Galvanic skin response (GSR), Heart rate, Skin temperature, Quality of life, Critical and Non-critical Units, Staff Nurses

Cite this paper: Rakesh Sharma, Deepak Goel, Malini Srivastav, Renu Dhasmana, Psycho-Physiological Parameters of Nurses in Critical and Non-Critical Units, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 7 No. 5, 2017, pp. 107-110. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20170705.02.

1. Introduction

- Work stress has been characterized as a predecessor or stimulus, as a consequence or response, and as an interaction. It has been studied from many different frameworks. It was proposed a physiological assessment that supports considering the association between stress and illness [1]. Contrarily, from a psychological perspective stress is “a certain relationship among individual and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her well-being” [2]. Nurses are trained to deal with factors such as a surrounded atmosphere, time forces, extreme noise or undue quiet, no substitute option, unpleasant sights and sounds, and long standing hours. Chronic stress takes a charge when there are added stress factors like family stress, fight at work, insufficient staffing, deprived teamwork, insufficient training, and poor administration. Stress is known to cause emotional exhaustion in nurses and lead to negative feelings toward those in their care. It is important to identify the extent and sources of stress in a healthcare organization to find stress management strategies to help the individual and the environment. Stress in nurses affects their health and increases absenteeism, attrition rate, injury claims, infection rates, and errors in treating patients [3, 4].Occupational stress and psychological well-being were negatively related to each other, whereas the greater the negative affectivity (fear, nervousness, range, guilt, contempt, disgust, sadness, loneliness, self-dissatisfaction and psychological distress) the lower the psychological well-being. Negative affectivity can be said to influence the perception of occupational stress and psychological well-being in such a way that individuals with high stress and high negative affectivity demonstrate low psychological well-being [5].Nurses’ cognitive and emotional factors influence their work performance; this reflects on patients who may receive inadequate care. It was observed that the changes in behavior and nurses made mistake 62 (92.9%), became aggressive 18 (30%), took hasty decision 56 (84.4%), lost interest 48 (72.9%), depressed 47 (71.4%) and became flustered 20 (32.9%). Further, nurses showed physical symptoms like headache 66 (98.6%), back pain 62 (92.9%), insomnia 56 (84.3%) etc. interms of psychological symptoms among nurses, fatigue 65 (97.1%), anxiety 65 (97.1), poor concentration 62 (92.9%) etc. Results of work stress effects the quality of health care therefore it is necessary to instigate to explore the connections between quality work environment and performance of nursing staff in hospitals [6, 7]. In acute pressure situation body is activate multiple physiological response to stressors. These physiological responses are rises heart rate, respiration rate, sweating, butterflies in the stomach, vomiting, widened pupils, and many more.Quality of life (QOL) is a broad-ranging concept, incorporating the person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, personal beliefs and their relationship with salient features of the environment. There are epidemiological studies on the QOL of healthcare workers in hospitals, where certain stressors influencing QOL can be found. Social support has been studied as a possible predictor of health-related QOL. Others have studied job stress in relation to general health, but do not cover all of the biological, psychological, social and environmental aspects of the World Health Organization (WHO) QOL definition [8].

2. Material and Methods

- A pilot study was conducted in the northern part of India at Urban Health Centre which is an extended health centre of tertiary care level Hospital. A baseline data was collected to assess the difference in quality of life and component of autonomic nervous system (Galvanic skin responses-GSR, Heart rate and skin temperature) of staff nurses posted in critical and non-critical units. Critical and non-critical units were classified based on patient’s acuity category [9, 10]. A total 12 staff nurses, 6 from critical units and 6 from non-critical units were included in the study with simple random technique method. Data were collected with demographic proforma, WHOQOL-BREF and computerized stress profile test. Demographic proforma consist of question regarding age, gender, marital status, educational qualification, professional work experience and average number of patient assignment to them. The WHOQOL-BREF consists of a total 26 five-point Likert scale questions gives a summary of quality of life. It is possible to derive four domain scores, namely physical health, psychological status, social relationship and environmental domains [11].The computerised stress profile test (CSPT) measures components of autonomic nervous system which includes heart rate, GSR, and skin temperature. The heart rate, GSR, skin temperature were recorded on a digital polygraph (Medicaid system, Chandigarh). A written consent was obtained from all the participants. Data were analysed with descriptive and inferential statistics.

3. Results

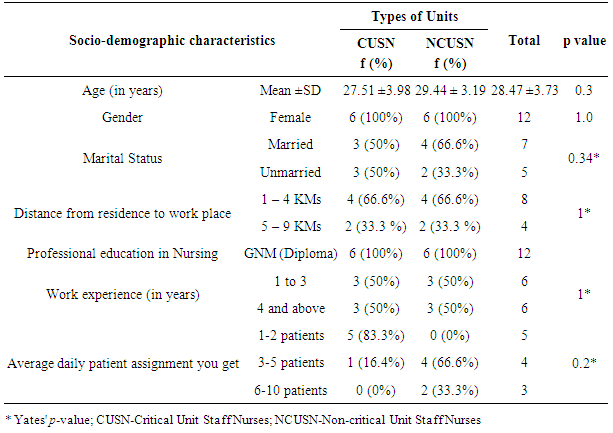

- Staff nurses posted in critical unit and non-critical units were equal with respect to an average age (27.51 ±3.98 years among CUSN and 29.44 ± 3.19 years NCUSN). All the nurses were female in both the groups. About marital status, half (50%) of staff nurses from critical units were married, whereas 66.6% of nurses from non-critical units were married. The majority (66.6%, 66.6%) of staff nurses reported that their residence was 1 – 4 kilometre away from the hospital among CUSN and NCUSN respectively (Table 1).

|

|

|

4. Discussion

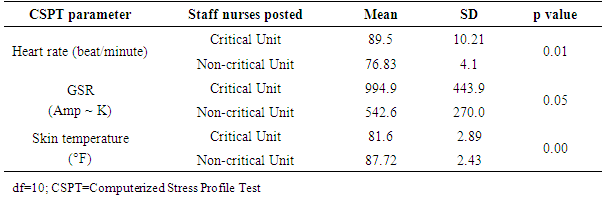

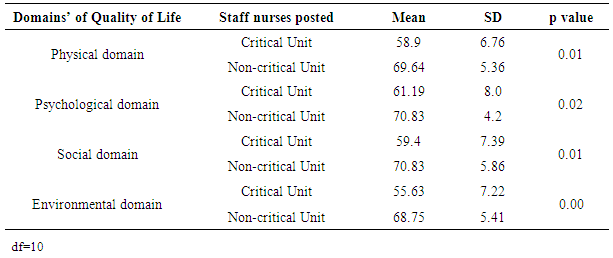

- Nurses posted in critical units work with high job demand as they have to continue to monitor critically ill patients with multiple medications, performing lifesaving procedures which are seen less often in non-critical units. In a study [12], it was found that the majority nurses’ heart rate was increased as work demand was high.Nurses posted in critical unit are not only physically stressed, but also psychologically, as they deal with critically ill patients and emotional reactions of patient’s relatives. This makes nurses more emotionally stressed, it was seen that heart rate was elevated during periods of negative emotional activities among healthy adults [13]. During psychological (emotional) or physiological strain the sympathetic nervous system gets activated which results into increased activity of sweat glands in the palms and tip of the fingers. This increases the conductivity of the skin. Present study findings also have shown similar phenomenon, the GSR score were higher among staff nurses posted in critical units than those posted in non-critical units. This shows the staff nurses posted in critical units were emotionally and physically aroused more than those posted in non-critical units. In a study conducted in the western part of India by [14] among healthy human and the GSR scores are similar with staff nurses posted in non-critical units. Under emotional reaction, sympathetically-mediated vasoconstriction produces a sudden decline in skin temperature, and this inflow of peripheral blood, along with stress prompted heat production, at the same time core temperature increases [15, 16]. The mean score of physical, psychological, social and environmental health of Staff nurses posted in non-critical units were higher than the staff nurses posted in critical units. Quality of life depends upon various factors such as illness, energy for everyday life, quality and pattern of sleep, support from others in day to day activities. Various studies from India [3, 17, 18] and from other countries [19-21] have been reported that the nurses suffered from many psychosomatic illnesses, which deteriorates the aspects of physical health from quality of life.

5. Conclusions

- The finding of the study showed that there were significant differences in the component of autonomic nervous system (heart rate, GSR, & skin temperature) as well as in the quality of life of staff nurses posted in critical and non-critical units. The study highlighted the over activity of autonomic response was higher in critical unit staff nurses than the staff nurses posted in non-critical units. Similarly, the quality of life was found better in non-critical unit’s staff nurses.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML