-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2017; 7(3): 71-78

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20170703.03

Contraception in Adolescent Postpartum: Attitude Assessment in Preventing Recurrent Pregnancy

Maria Lucia Neto de Menezes1, Maria das Neves Figueiroa2, Roberto José de Santana3, Renata Célia de Lira Neves3, Taynara Barbosa do Amaral Vilela3

1Obstetric nurse. MS in Hebiatrics from the University of Pernambuco (UPE), Assistant Professor at the School of Nursing “Nossa Senhora das Graças” of the UPE. Ph.D. Student in Child and Adolescent Health at the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), Recife, PE, Brazil

2Obstetric Nurse, Ph.D. in Molecular and Tissue Biology, Professor at the University of Pernambuco (UPE), Recife (PE), Brazil

3Resident in Women’s Health with an Emphasis on Obstetrics from the Pernambuco State Department of Health and the Integrated Health Center “Amaury de Medeiros” (CISAM). Recife, PE, Brazil

Correspondence to: Maria das Neves Figueiroa, Obstetric Nurse, Ph.D. in Molecular and Tissue Biology, Professor at the University of Pernambuco (UPE), Recife (PE), Brazil.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Adolescence is a period of doubt and uncertainty, involving risk attitudes and exposure to emotional and physical damage. Cross-sectional epidemiological study with a quantitative approach, aiming to analyze the positive attitude of pregnant teenagers, from the perspective of adopting contraceptive methods in the puerperium. Fifty adolescents were interviewed in an outpatient clinic in Recife, PE, Brazil. The health prevention attitude was associated by means of the sociodemographic dimensions and health behavior. The analysis of adolescent exposure to factors that compromise the ability to prevent recurrent pregnancy has been linked both to concrete existing conditions of the first dimension and to health perception and behavior of the second dimension.

Keywords: Adolescent health, Pregnancy in adolescence, Health attitude, Adolescent behavior, Contraceptive behavior

Cite this paper: Maria Lucia Neto de Menezes, Maria das Neves Figueiroa, Roberto José de Santana, Renata Célia de Lira Neves, Taynara Barbosa do Amaral Vilela, Contraception in Adolescent Postpartum: Attitude Assessment in Preventing Recurrent Pregnancy, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2017, pp. 71-78. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20170703.03.

1. Introduction

- Adolescence is a period between 10 and 19 years of age [1, 2], when the individual undergoes intense physical and psychological changes [3], who begins to interact with the world around her more independently. In this context, the young person finds herself in a situation where there is no way to act as a child anymore, although lacking total autonomy over her life, sometimes taking risk attitudes towards health and compromising physical integrity [4], such as unsafe sex with exposure to sexually transmitted diseases and, above all, unwanted and recurrent pregnancies.National and international statistical data emphasize the significant increased number of pregnant teenagers in various countries. According to estimates, about 16 million women between 15 and 19 years of age get pregnant every year in the world. Out of these births, 95% occur in low- and medium-income countries. In Latin America, the percentage is around 18%, half of which occur in only 7 countries, among them Brazil [5]. Such data raise concerns, because faced with this reality there is a reduced expectation of these girls to complete their studies, to have a stable job, and to be independent [6, 7]. Also, with short intergestational intervals, teenagers with recurrent pregnancies are more exposed to hemorrhages in the third trimester, anemia, puerperal endometritis, premature rupture of membranes, obesity, and gestational diabetes [8].It is known that many of these adolescents in early sexual life have doubts about the contraceptive methods available and the best method to adopt [3]. Uncertainties such as these are related to the concept of positive attitude in prevention, which is defined as an individual seeking care, regardless of the fact whether she or the group to which she belongs is experiencing a health problem [9, 10].Such an attitude is determined by an individual’s beliefs and perceptions about what health, illness, and prevention are, in addition to her experiences, either for health prevention, maintenance, or treatment. In relation to the concept, it is known there are two dimensions constituting it and they can influence attitudes. The first dimension refers to an individual’s concrete existing conditions, characterized by the socioeconomic status. In turn, the second concerns health perceptions and behaviors, being characterized by the identification of a health problem and the search for a solution by the individual [9, 10].The issue that led to our interest in conducting this study derived from the concern with repeated pregnancies in adolescence, thus, the authors were interested in addressing the attitude towards the perspective of adopting contraceptive methods by teenagers in the postpartum period.

2. Methods

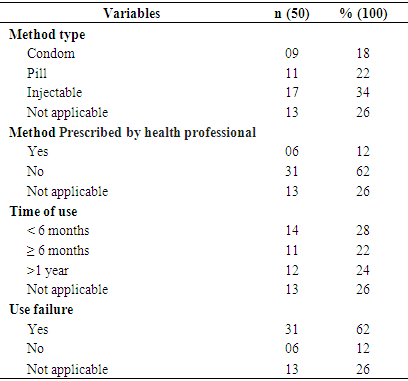

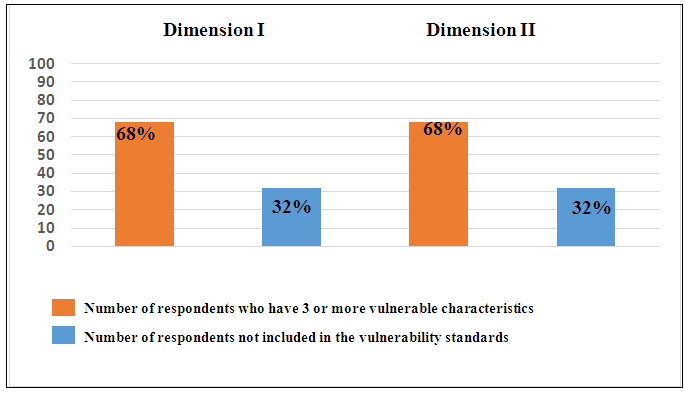

- This is a cross-sectional epidemiological study, carried out within the period from February to May, 2015, at the outpatient clinic of a reference maternity hospital that provides high-risk care in Recife, PE, Brazil. The population consisted of adolescent pregnant women attending prenatal, low and high risk outpatient appointments. Considering a monthly average of appointments, evaluated within a 7-month period, through data provided by the administrative department of the teaching hospital, which corresponded to a total around 835 appointments, the sampling calculation consisted of 50 pregnant women, and the sample was delimited using the software Raosoft Sample Size Calculator.The final sample gathered adolescent pregnant women whose appointments took place during the data collection period, who were psychically and physically fit and freely accepted to participate in the research, confirming it either by their signature or by their guardians’ signature.Data was collected by means of an interview conducted using a script prepared by the authors, containing variables related to the sociodemographic profile and the sexual, reproductive, and contraceptive behavior, as well as the characteristics related to reproductive risk.To analyze the attitude towards prevention, the data collected were categorized according to two dimensions: sociodemographic characteristics and health behavior (Figure 1). After categorization, the subjects most vulnerable to having a positive attitude deficit concerning prevention were identified among those who had three or more risk indicators in each dimension.

| Figure 1. Organization chart representing vulnerable groups and their characteristics regarding the positive attitude in prevention. Recife, PE, 2015 |

3. Results

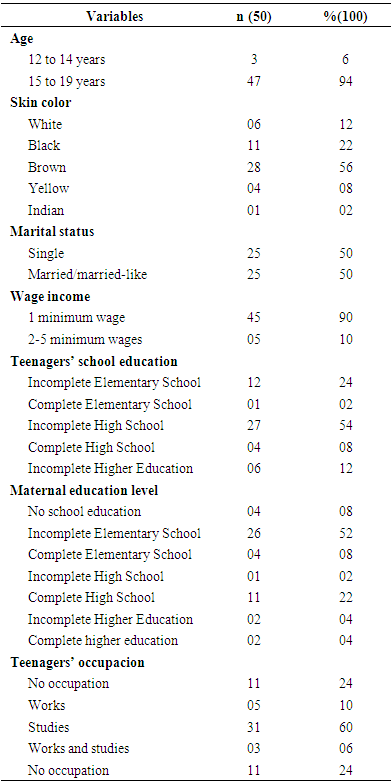

- Before analyzing the sociodemographic data (Table 1), it was noticed there was a prevalence of pregnant women aged from 15 to 19 years (94%), followed by 12 and 14 years (6%). Regarding skin color, there was predominance of African descent, with 56% for brown and 22% for black people. Some of the pregnant women (50%) claimed to be married or married-like, while the remaining 50% reported to be single and live with their parents. As for family income, the majority (90%) declared to have only 1 minimum wage for family expenses.

|

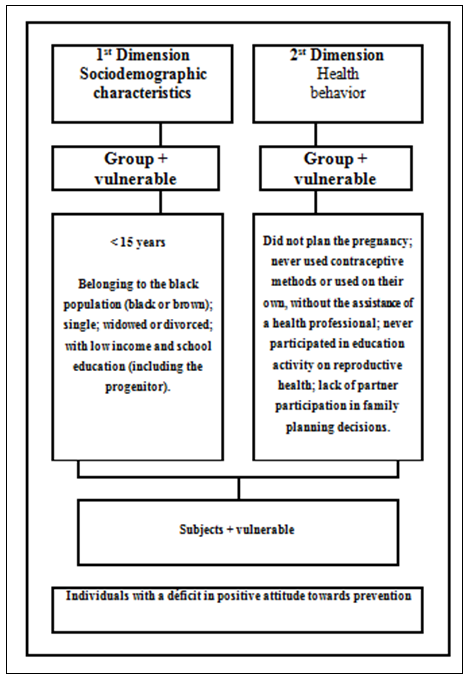

| Graph 1. Habits and addictions of pregnant teenagers interviewed at an outpatient teaching hospital facility (n = 50). Recife, PE, 2015 |

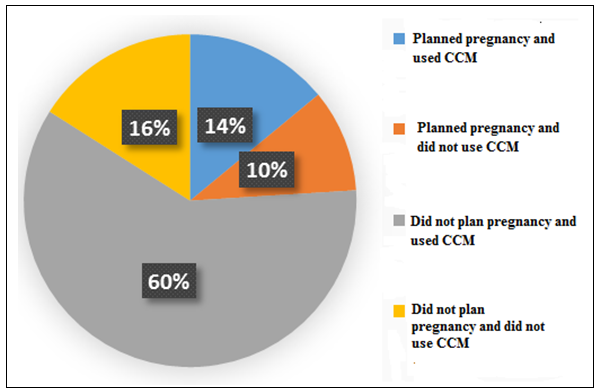

|

|

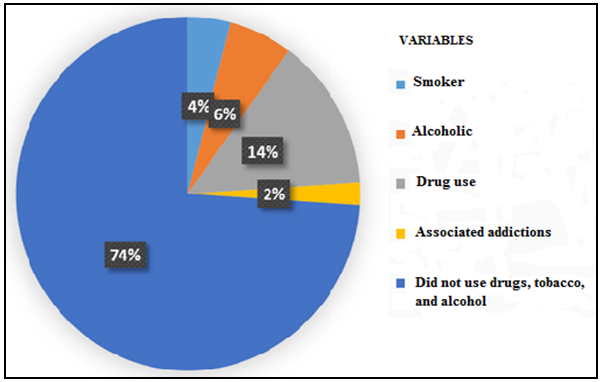

| Graph 2. Behavior of the adolescent pregnant women interviewed, in face of family planning related to the use or not use of a contraceptive method (CCM) (n = 50). Recife, PE, 2015 |

|

| Graph 3. Variables referring to adolescent pregnant women who had 3 or more vulnerable characteristics in the two dimensions above, which shows a deficit in positive attitude towards prevention (n = 50). Recife, PE, 2015 |

4. Discussion

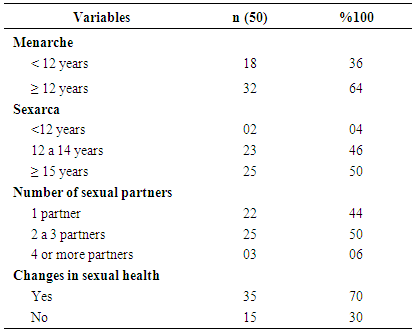

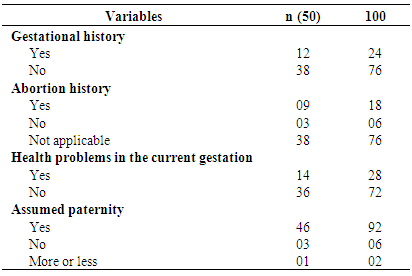

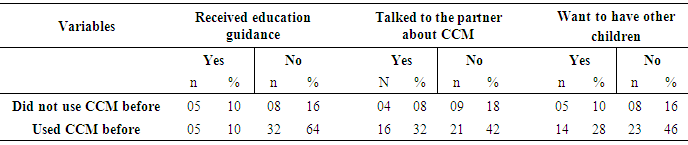

- Most pregnant women interviewed in this study were aged between 15 and 19 years, something which coincides with data from other surveys that confirm 11% of annual births worldwide from teenagers within the same age group [11, 12]. In other studies whose purpose is analyzing the magnitude and characteristics related to recurrent pregnancy in adolescence, one of the main associated factors was also age between 15 and 19 years [13]. There was a predominance of African descent (78%), which is in line with other surveys, where most teenagers interviewed were brown and black [14, 15]. In the analysis of marital status, we notice that while on the one hand there is early marital union, contributing with social disadvantages, since the teenagers are limited to the role of mother and housewife, dropping out of school and, consequently, giving up the chance of vocational qualification [14], on the other hand, the young woman remains within their family environment, perhaps due to the low income level, accompanied by the prejudice imposed by the society and the responsibility of having another family member to educate and feed [16].Therefore, in this study there was no difference for the variable marital status. Unlike some studies showing divergent results, since some data show a higher proportion of teenagers in a marriage-like relationship [17, 18], others confirm a prevalence of unmarried teenagers who do not live with their partners [13, 19]. It is worth emphasizing that most of the existing marital unions do not necessarily imply the couple financial independence or responsibility concerning care for the newborn infant, and this may be a factor motivated by pregnancy itself and social pressure. In this regard, health education is significant, especially for primary care professionals, since these teenagers need family support to pursue their routine activities, such as study, work, responsibility towards the baby, and contraception within the postpartum period through family planning [18].As for family income, this study revealed that 90% of the teenagers depended on only 1 minimum wage, something which converges with other surveys, referring to low income in 83.3%, 41.17%, and 90.4%, respectively, of the teenagers interviewed [7, 14, 18]. Such data associate low family income with the increased risk of early and recurrent pregnancies [7].The variable school education showed a difference from other studies, which pointed out a low education level in most teenagers, indicating this factor as one of the main consequences of pregnancy within this age group [7, 17, 18, 20]. However, although this study had a High School education in most of the teenagers, a low education level was observed in the majority of these respondents’ mothers. It is known that a low education level of a teenager’s mother is a factor that can lead to inadequate sexual information, since guidance needed for a good sex education depend not only on the school, but also on the family environment. So, difficulties in the dialogue about sexuality lead to prejudice in thoughts about the significance of using adequate contraceptive methods, something which contributes to unplanned and recurrent pregnancies [7, 17, 21].Although most respondents reported no addictions, about 1/3 confirmed to use alcohol and other drugs (cigarette, marijuana, cocaine, hallucinogenic inhalants), with associated addictions among these illicit drugs. Such data are worrisome, especially because this is a group still at the stage of physical, psychic, and social growth, whose sexuality emerges as a way of expressing emotions and attitudes, reflected according to the environment where they live. Thus, in face of a physical and psychic burden, such as early pregnancy itself, teenagers are more prone to risky behaviors, such as exposure to alcohol and other drugs, a behavior that usually arises only due to their very exploratory nature or because of the influence of environment, and this may contribute to a series of obstetric and perinatal complications [22].The respondents’ gynecological and obstetric profile of is very similar to that developed by other authors whose work shows an early menarche among the teenagers interviewed [17, 18]. It is known that, recently, the age of menarche has started earlier in society, due to factors such as secular growth acceleration, environmental context changes, genetic factors, besides variables such as ethnicity, socioeconomic level, and nutritional status. This menarche can still be mentioned as a factor capable of stimulating the onset of sexual activity among these teenagers, whose body is at this transition stage and psychological immaturity may attribute inherent health risks, such as unwanted and recurrent pregnancy [15, 17, 23].Thus, in this study, early first sexual intercourse was a factor that drew attention, since the average age for the first sexual experience was 15 years, something which is in line with other studies, also referring to such precocity [7, 14, 17, 18, 24].The number of reports associated with complaints and genital pathologies has drawn attention. These data suggest these teenagers’ exposure to gynecological problems and lack of sexual protection, because, as it is well known, the risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) increases significantly along with each new sexual partner and an increased number of partners [25].The first pregnancy allied to an early first sexual intercourse increases chances of recurrent pregnancy at this life phase [15, 26], a theory that could be observed in the expression of the number of multigravidas. Many of the latter have reported a history of abortion, something which shows an unfavorable scenario for these teenagers, since abortion is sometimes recognized as the only resource left for unprotected in the case of unwanted pregnancy [27].The prevalence of teenagers who reported health changes in the current pregnancy was almost 1/3 of those interviewed. Most intercurrences are common in early pregnancy, since physiological immaturity to withstand pregnancy stress may represent a high risk of unfavorable obstetric outcome, something which leads mainly to fetal growth deficit, prematurity, and low birth weight [19]. It is also worth mentioning that these risks may be related to low adherence to prenatal care, something which allows identifying risk situations and performing early and efficient interventions [18, 28].Although most respondents reported assumed paternity, there were problems regarding partner acceptance in about 10% of the cases, a percentage that, although low, deserves attention, because besides inadequate to prenatal care, other factors, such as absence of partner and lack of pregnancy acceptance by the family or partner may interfere with the health and well-being of the adolescent pregnant woman, and this contributes to adverse conditions to fetal growth and development [28, 29].It was found that most of the teenagers did not plan pregnancy and got pregnant even resorting to CCM, along with lack of education guidance concerning the use of CCM. These data reinforce the theory that lack of guidance on sexuality and adequate contraception exposes these girls to risks such as sexual infections and unwanted and recurrent pregnancies [17]. It is worth noticing that almost 20% of the respondents stated they did not plan pregnancy, but they did not use any contraceptive method. According to the literature on the theme, factors such as ignorance and neglect are related to lack of use of contraceptive methods in adolescence. These data reinforce the evidence that the earlier the first sexual intercourse occurs in adolescence, the greater the chances of a pregnancy during this period of life, due to the non-use of contraceptive methods, or the difficulty of access, fear to seek health services, ignorance of preventive practices, or the imagination of a supernatural world by adolescents, where nothing bad will happen to them [17].It is worth highlighting the perception there is a deficiency in the dialogue on CCM between partners, something which draws attention, as dialogue, specifically between partners, can stimulate the exchange of knowledge acquired about sexuality and contraception, as well as contribute both to choose and to effectively and skillfully use the selected contraceptive method [24].Similar to other studies, it was found that contraceptive methods, injectable and oral, as well as condoms, were the most frequently adopted by teenagers. These data are still close to the evidence provided by another study, where the contraceptives most frequently mentioned by adolescent puerperal women were the pill, followed by the condom [17]. In this context, the lack of care for adolescents in relation to STI prevention is highlighted, since few reported the use of condoms as a precaution [17]. Another major point might be the fact that the vast majority of the respondents used contraceptive methods on their own, without guidance by a health professional, something which reveals a lack of interest of these young women in seeking a health service to get information about sexuality and contraception. It is noteworthy there was pregnancy after a short period using contraceptive methods and most of the respondents reported failures regarding their use. Such failures are surely related to lack of demand for adequate information on sexual and reproductive health, as evidenced by another study, where the majority of sexually active teenagers did not seek family planning services, nor did they ask for advise by nurses or physicians about The information mentioned above [25].It is known that adolescents are recognized by their low demand for health services, and this requires an initiative of services and professionals, in order to increase the attempt to attract these teenagers to primary care services. It is also worth mentioning the use of all appointments with these teenagers to inquire about their sexuality and to provide individualized guidance, besides the significance that nurses from these facilities in health education actions on sexuality, also in the schools [25].When analyzing the vulnerability index, it was found that most teenagers had 3 or more characteristics, both in the first and second dimensions, related to attitude, something which may compromise the capacity of adopting preventive measures.In the analysis of the first dimension, we observed factors associated with vulnerability such as: skin color (black and brown); low school education of adolescent and low-income mothers. Through the second dimension survey, the elements highlighting vulnerability were: unplanned pregnancy, lack of education guidance on contraception, use of self-employed CCM, and lack of partner participation in family planning decisions.

5. Conclusions

- The analysis of adolescent exposure to factors that affect their ability to prevent recurrent pregnancies has been linked both to concrete existing conditions of the first dimension and to health perception and behavior of the second dimension. The results point out the importance of a look at teenage pregnancy as an issue that goes beyond economic and biological aspects, becoming a concern of a social nature. Data reveal the importance of teenage recruitment for health education services, seeking peer commitment in an attempt to establish a healthy and safe experience as for sexuality.

References

| [1] | C. A. S. Garbin, D. P. Lima, A. P. Dossi, R. M. Arcieri, T. A. S. Rovida. “Percepção de adolescentes sobre doenças sexualmente transmissíveis e métodos contraceptivos,” DST J Bras Doenças Sex Transm, vol. 22, pp. 60-63, 2010. |

| [2] | J. M. Hartmann, J. A. Cesar. “Conhecimento de preservativo masculino entre adolescentes: estudo de base populacional no semiárido nordestino, Brasil,” Cad Saúde Pública, vol. 29, pp. 2297-2306, 2013. |

| [3] | M. V. Giordano, L. A. Giordano. “Contracepção na adolescência,” Adolesc Saúde, vol. 6, [s.p], 2009. |

| [4] | P. V. C. Lima, A. K. Rodrigues, R. S. Costa, R. D. Rocha. “Saúde do adolescente: conceitos e percepções - revisão integrativa.” Rev Enferm UFPE On Line, vol. 8, pp. 146-154, 2014. |

| [5] | B. B. Buendgens, M. F. M. Zampieri. “A adolescente grávida na percepção de médicos e enfermeiros da atenção básica.” Esc Anna Nery Rev Enferm, vol. 16, pp. 64-72, 2012. |

| [6] | L. N. Lewis, D. A. Doherty, M. Hickey, S. R. Skinner. “Predictor of sexual intercourse and rapid-repeat pregnancy among teegage mothers: an Australian prospective longitudinal study.” MJA, vol. 193, pp. 338-342, 2010. |

| [7] | A. A. A. Silva, I. C. Coutinho, L. Katz, A. S. R. Souza. “Fatores associados à recorrência da gravidez na adolescência em uma maternidade escola: estudo caso-controle.” Cad Saúde Pública, vol. 29, pp. 496-506, 2013. |

| [8] | C. S. Vieira, M. B. Brito, M. E. H. D. Yazlle. “Contracepção no puerpério.” Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet, vol. 30, pp. 470-479, 2008. |

| [9] | M. E. W. Cestari, M. M. F. Zago. “A prevenção do câncer e a promoção da saúde: um desafio para o Século XXI.” Rev Bras Enferm, vol. 58, pp. 218-221, 2005. |

| [10] | A. A. M. Cardelli, A. C. A. Tanaka. “O papel das crenças e percepções das mulheres na vivencia do processo saúde-doença.” Ciênc Cuid Saúde, vol. 11, pp. 108-114, 2012. |

| [11] | World Health Organization, 2011. Adolescent pregnancy. Available from: http://www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/topics/adolescent_ pregnancy/en/index.html. |

| [12] | Í. R. Chinazzo, G. Câmara, G. Frantz. “Comportamento sexual de risco em jovens: aspectos cognitivos e emocionais.” Psico-USF, vol. 19, pp. 1-12, 2014. |

| [13] | K. S. Silva, R. Rozenberg, C. Bonan, V. C. C. Chuva, S. F. Costa, M. A. S. M. Gomes. “Gravidez recorrente na adolescência e vulnerabilidade social no Rio de Janeiro (RJ, Brasil): uma análise de dados do Sistema de Nascidos Vivos.” Ciênc Saúde Coletiva, vol. 16, pp. 2485-2493, 2011. |

| [14] | S. C. Oliveira, M. G. L. Vasconcelos, E. C. A. Oliveira, P. J. A. Vasconcelos Neto. “Análise do perfil de adolescentes grávidas de uma comunidade no Recife-PE.” Rev RENE, vol. 12, pp. 561-567, 2011. |

| [15] | E. F. Viellas, S. G. N. Gama, M. M. Theme Filha, M. C. Leal. “Gravidez recorrente na adolescência e os desfechos negativos no recém-nascido: um estudo no Município do Rio de Janeiro.” Rev Bras Epidemiol, vol. 15, pp. 443-454, 2012. |

| [16] | J. Á. Taborda, F. C. Silva, L. Ulbricht, E. B. Neves. “Consequências da gravidez na adolescência para as meninas considerando-se as diferenças socioeconômicas entre elas.” Cad Saúde Colet, vol. 22, pp. 16-24, 2014. |

| [17] | F. S. Rosa, D. Cecagno, S. M. K. Meincke, S. S. Bordigno, M. C. Soares, A. C. L. Corrêa. “Uso de contraceptivos por puérperas adolescentes.” Avances en Enferemería, vol. 32, pp. 245-251, 2014. |

| [18] | M. V. O. Queiroz, E. G. M. Brasil, C. M. Alcântara, M. G. O. Carneiro. “Perfil da gravidez na adolescência e ocorrências clínico-obstétricas.” Rev RENE, vol. 15, pp. 455-462, 2014. |

| [19] | A. B. F. Campos, R. A. Pereira, J. Queiroz, C. “Saunders. Ingestão de energia e de nutrientes e baixo peso ao nascer: estudo de coorte com gestantes adolescentes.” Rev Nutr, vol. 26, pp. 551-561, 2013. |

| [20] | A. S. Sousa, N. A. Andrade, H. G. L. Sousa, O. B. Quental, M. V. S. Sobreira, K. A. Soares. “Complicações obstétricas em adolescentes de uma maternidade.” Rev Enferm UFPE On Line, vol. 7, pp. 1167-1173, 2013. |

| [21] | M. C. R. Sousa, K. R. O. Gomes. “Conhecimento objetivo e percebido sobre contraceptivos hormonais orais entre adolescentes com antecedentes gestacionais.” Cad Saúde Pública, vol. 25, pp. 645-654, 2009. |

| [22] | T. D. Lopes, P. P. Arruda. “As repercussões do uso abusivo de drogas no período gravídico/puerperal.” Revista Saúde e Pesquisa, vol. 3, pp. 79-83, 2010. |

| [23] | F. Pedro Filho, R. M. S. Sigrist, L. L. Souza, D. C. Mateus, E. Rassam. “Perfil epidemiológico da grávida adolescente no município de Jundiaí e sua evolução em trinta anos.” Adolesc Saúde, vol. 8, pp. 21-27, 2011. |

| [24] | N. D. Patias, A. C. G. Dias. “Sexarca, informação e uso de métodos contraceptivos: comparação entre adolescentes.” Psico-USF, vol. 19, pp. 13-22, 2014. |

| [25] | M. M. S. R. S. Ferreira, M. C. L. F. P. R. Torgal. “Estilo de vida na adolescência: comportamento sexual dos adolescentes portugueses.” Rev Esc Enferm USP, vol. 45, pp. 589-595, 2011. |

| [26] | L. N. B. Moura, K. R. O. Gomes, C. R. O. Sousa, T. A. Maranhão. “Multiparidade entre adolescentes e jovens e fatores de risco em Teresina/Piauí.” Adolesc Saude, vol. 11, pp. 51-62, 2014. |

| [27] | J. H. B. Chaves, L. Pessini, A. F. S. Bezerra, G. Rego, R. Nunes. “A interrupção da gravidez na adolescência: aspectos epidemiológicos numa maternidade pública no nordeste do Brasil.” Saúde Soc, vol. 21, pp. 246-256, 2012. |

| [28] | N. L. A. Cruz Santos, M. C. O. Costa, M. T. R. Amaral, G. O. Vieira, E. B. Bacelar, A. H. V. Almeida. “Gravidez na adolescência: análise de fatores de risco para baixo peso, prematuridade e cesariana.” Ciênc Saúde Coletiva, vol. 19, pp. 719-726, 2014. |

| [29] | D. S. Correia, L. V. A. Santos, A. M. N. Calheiros, M. J. Vieira. “Adolescentes grávidas: sinais, sintomas intercorrências e presença de estresse.” Rev Gaúch Enferm, vol. 32, pp. 40-47, 2011. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML