-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2017; 7(1): 16-27

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20170701.02

Relationship between Level of Self-Efficacy and Self-Management; Hemodialysis versus Oncology Related Fatigue

Wafaa H. Abdullah 1, Elham Abdullah El Nagshabandi 2

1Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Menoufia University, Egypt

2Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA

Correspondence to: Wafaa H. Abdullah , Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Menoufia University, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Fatigue is a distressing symptom in patients with advanced cancer. The use of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic strategies has resulted in advances of managing cancer-related fatigue. Aim: To investigate the relationship between self-management and level of self-efficacy among hemodialysis versus oncology related fatigue. Design: Descriptive analytical research design was utilized. Setting: Hemodialysis unit of the outpatient and medical in patient ward at king Abdulaziz university hospital, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Subjects: A convenience sample which consists of 111 adult patients divided into 37 oncology hospitalized patients and 74 Hemodialysis patients. Tools: 1. Participant characteristics questionnaire was developed to assess demographical data. 2. Fatigue scale had been adapted to quantify the magnitude of fatigue. 3. Self-efficacy scale had been adapted to assess optimistic self-beliefs of coping in order to face difficulties of illness demands in life. Results: Patients ability to keep calm during difficulties and relied on ability to cope were found to be moderately true among 52.7% of hemodialysis compared to 75.5% oncology patients with statistical significant difference of less than 0.05. As regard to fatigue level, 45.1% of hemodialysis patients agreed that “easy I feel tired” compared to 78.4% oncology patients with statistical difference of less than 0.05. Conclusions: There is an evident of negative correlation between fatigue and self-efficacy as fatigue increases, self-efficacy decreases. The proper fatigue management resulted in increase in self-efficacy. Recommendations: Nurses need to assess fatigue levels among patients who are either receiving chemotherapy or hemodialysis. Also nurses need to exert efforts and spend quality time with chronic fatigue patients and find means to raise self-efficacy to modify and better manage it.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, Oncology, Fatigue, Self-management, Self-Efficacy

Cite this paper: Wafaa H. Abdullah , Elham Abdullah El Nagshabandi , Relationship between Level of Self-Efficacy and Self-Management; Hemodialysis versus Oncology Related Fatigue, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 16-27. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20170701.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Fatigue is a distressing symptom in patients with advanced cancer. Although the use of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic strategies has resulted in advances in managing of cancer-related fatigue. Unfortunately, it is not well-managed by patients with advanced cancer. Recognition regarding the benefits of self-management in managing most of chronic conditions has increased [1]. The prevalence of diagnosable cancer related fatigue of patients who had completed treatment more than 1 year ago, were 17% lower than expected based on previous reports that have used less-strict criteria [2]. Lifestyle changes, such as exercising more, relieving stress, and eating healthy, well-balanced diet can help ease fatigue [3]. Also education of fatigue management and adequate information regarding self-help measures were valuable in helping subjects deal with the side effects of chemotherapy [4]. As regard hemodialysis in Menofia Governorate, Egypt, [5] reported that the prevalence rate of Hemodialysis (HD) represents 414 patients per million populations (pmp). The mean age was 52.03 + 14.67 years, 60.3% male and 39.7 female. The mean duration of dialysis was found to be 41.23 + 37.59 months. There is a high prevalence rate of hemodialysis which represents the only mode of treatment of ESRD patients. Chronic kidney disease is a worldwide health problem. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is unpredictable and patients may not feel ill as the disease progresses to end stage renal disease (ESRD), an illness that affects over 593,000 people in the U.S [6]. Patients in the end-stage renal disease phase have two options in order to stay alive: life-long dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) or kidney transplantation. Of these options, dialysis is considered the treatment of choice. Patients on hemodialysis account for approximately 92% of the overall dialysis population [6] and endure a high symptom burden as they may experience troubling symptoms such as fatigue, decreased appetite, trouble concentrating, swelling in their feet and hands, muscle cramps, and itching [7-9]; all of which cause daily distress and negatively affects their quality of life [10, 11]. Patients on hemodialysis must find ways to manage their fatigue and mitigate its effects on their lives [12]. Collaborative relationship between patients and care providers is the basis of effective self-efficacy in care is particularly with emphasis on their self-care aspects [13]. Patients on hemodialysis should receive regular healthcare for the rest of their lives (usually three times a week, each time three to four hours). Although dialysis can increase the lifespan of the patient, it cannot alter the natural course of renal disease and fully replace the renal function; as a result, patients experience numerous complications and problems. The clinical findings in these patients are non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, lethargy, pruritus, amnesia, loss of sexual desire, and nausea. Chronic renal failure (CRF) or end stage renal disease ESRD is one of the major causes of death and disability worldwide. The outbreak of kidney failure in European countries has increased by 30% and has an uptrend in Iran as well; it has been predicted that by the year 1400, there will be over 95 thousand renal patients in Iran [14]. General self-efficacy refers to a global confidence in coping abilities across a wide range of demanding situations and reflects a person’s general problem-solving ability. Significant associations between higher general self-efficacy and physical health, better mental and physical health related quality of life (HRQoL). Increased physical functioning, and increased cancer specific health related quality of life (HRQoL) have been demonstrated in patients with NET, higher general self-efficacy was associated with better mental and physical HRQoL [15].The self-management program is based on behavior change theories, focusing on alterations in daily life activity performance (values), prioritizing, task duration, alternation between physical and mental activity, etc. The activity pacing self-management program consists of a stabilization phase and a grading phase. The stabilization phase focuses on coaching clients in how to perform daily life activities within the limits of their actual capacity. Daily life activities were defined as all responsibilities and desired activities in the areas of personal and child care, domestic care, productivity, and leisure. To appropriately pace activities, participants were instructed to estimate their current physical and mental capabilities (in terms of activity duration) before commencing an activity, keeping in mind the fluctuating nature of their symptoms [16, 17]. The activity duration advised within the program was 25%–50% lower than the capacity participants reported to account for any overestimations. Each activity block was interspersed with breaks, with the length of each break equal to the duration of the activity. Breaks were defined as relative periods of rest, with the participant just relaxing or performing a different type of light activity. The emphasis on breaks is based on the observation that recovery from physical exertion is prolonged in people with chronic fatigue syndrome [18-20]. The process of restructuring activity patterns involves significant behavioral change for people with chronic fatigue syndrome, and facilitation of this process can be beneficial [21]. Stress is an important factor in the persistence of fatigue; therefore, relaxation may be a crucial component in the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. The relaxation program for this study comprised education about the role of stress in chronic fatigue syndrome biology and the opportunities that stress management provides [22]. The activity pacing self-management program shows evidence of being a feasible and effective intervention to optimize performance of and satisfaction with desired daily life activities and to decrease fatigue in women with chronic fatigue syndrome [23].

2. Aim of the study

- To investigate the relationship between self-management and level of self-efficacy among hemodialysis versus oncology related fatigue.Research questions:Ÿ What is the relationship between fatigue level and level of self-efficacy among hemodialysis versus oncology patient?Ÿ What is a relationship between fatigue self-management of and level of self-efficacy among hemodialysis versus oncology patients?Operational definition:Self-efficacy beliefs determine how people feel, think, motivate themselves and behave. Such beliefs produce these diverse effects through four major processes. They include cognitive, motivational, affective and selection processes [27].

3. Subject and Method

- Design:Descriptive and analytical research design was utilized for this study.Setting:The study was conducted at the hemodialysis unit of the outpatient and medical in patient ward at king Abdulaziz university hospital, Jeddah as it the teaching hospital. Subjects:Ÿ A convenience sample consists of 111 Adult patients divided into 37 oncology hospitalized patients and 74 Hemodialysis patients with the following criteria:§ Inclusion criteria:× Adult× Male or female× Saudi or non-Saudi § Exclusion criteria:× Terminally ill oncology patients× Children

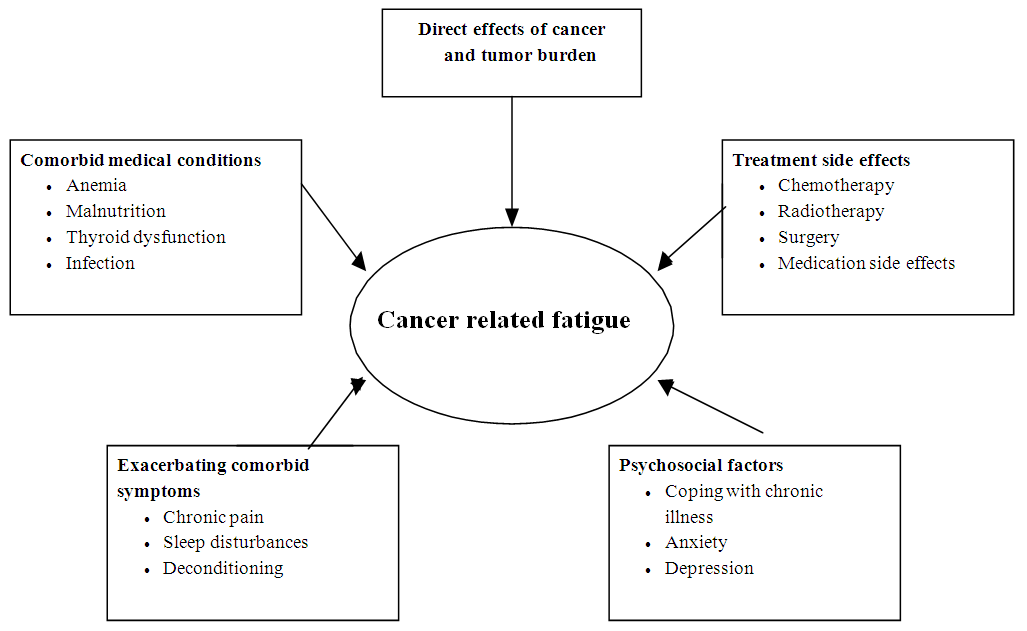

| Figure (1). Causes of fatigue [24-26] |

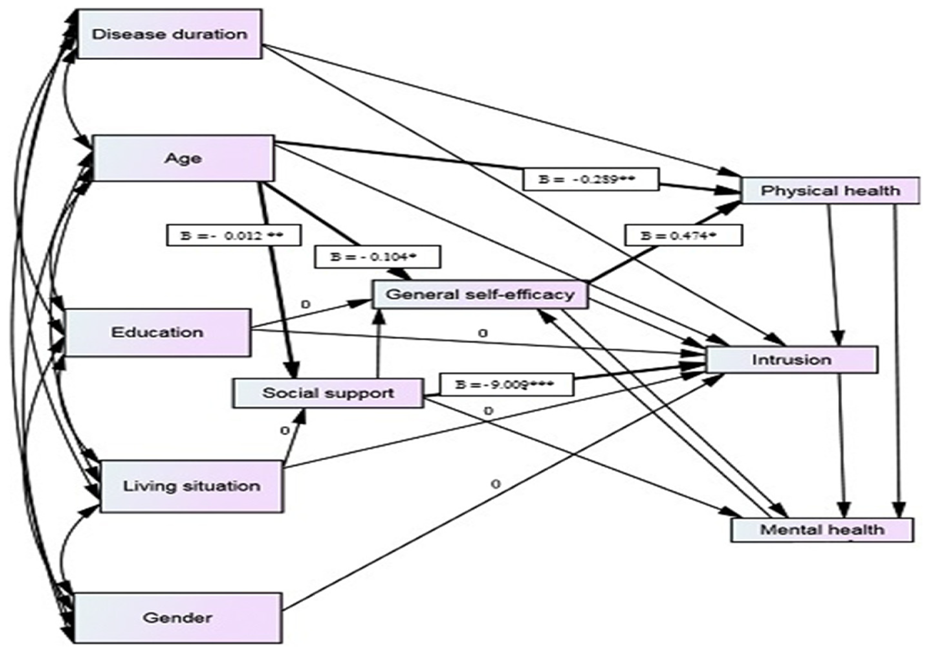

| Figure (2). A Path diagram of direct and indirect influences of general self -efficacy, social support, cancer related- stress and health -related mental and physical components of life [15] |

4. Results

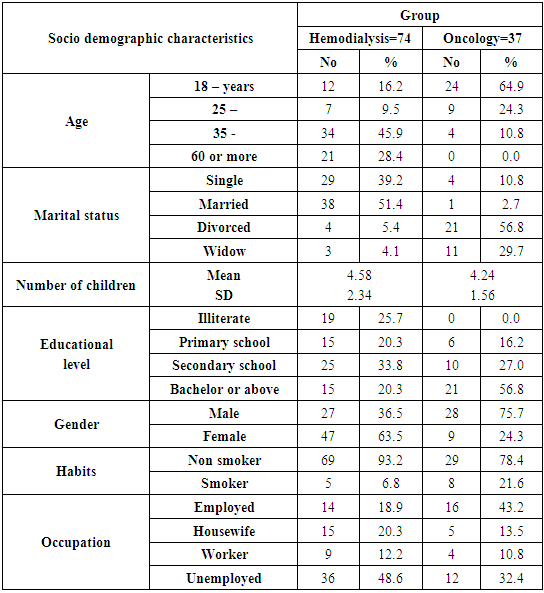

- Table (1) Demographic properties of the participants, 45% of the Hemodialysis patients were between the ages of 35-59 years as it compared to 64.9% Oncology patients were between the ages of 18-24 years. Gender wise, 63.5% of the Hemodialysis patients were females while 75.5% were males among Oncology patients. Smoking as a habit was revealed that majority of Hemodialysis patients were nonsmokers, while 78.4% of Oncology patients were nonsmokers. Among Hemodialysis versus Oncology, revealed that 93.2% and 78.4% were non-smoker respectively.

|

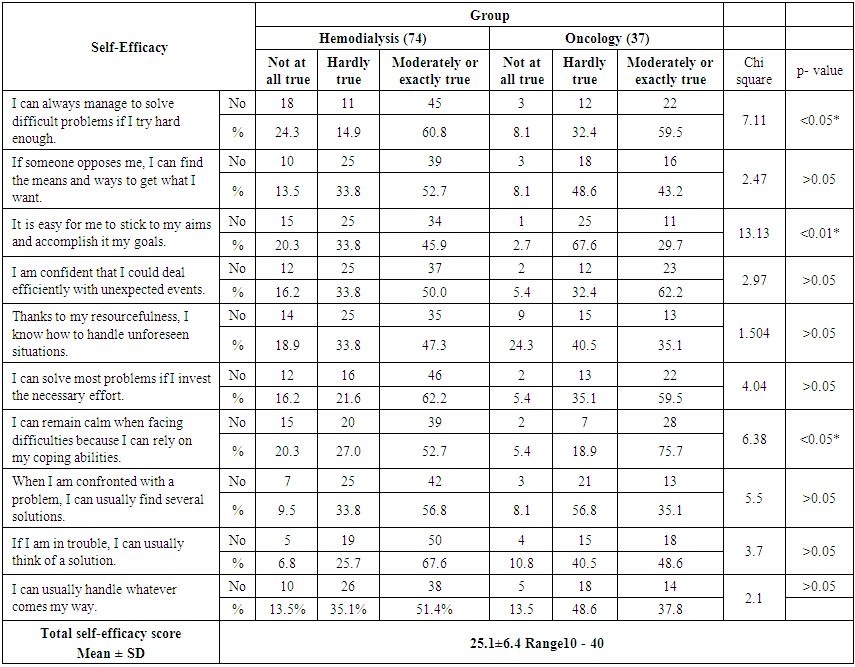

| Table (2). Distribution of Self-efficacy level among Hemodialysis versus Oncology patients |

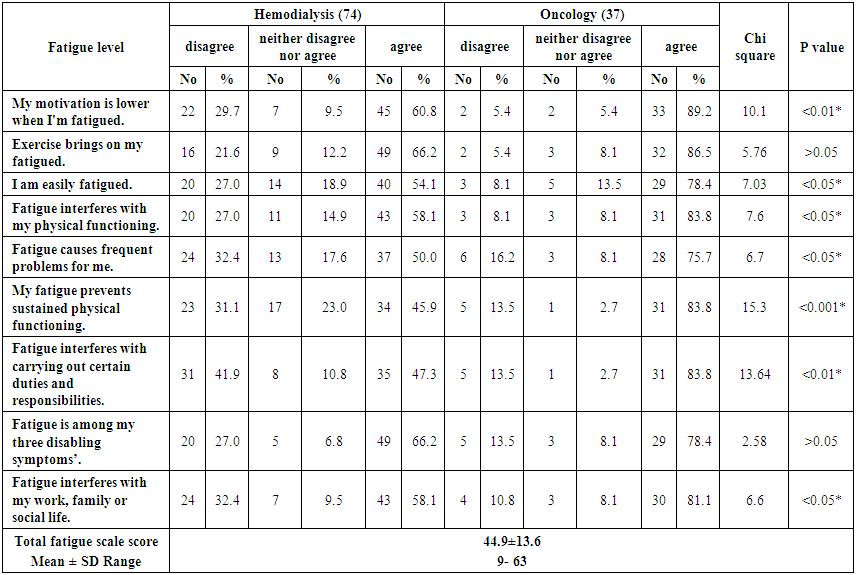

| Table (3). Distribution of fatigue level among Hemodialysis versus Oncology patients |

|

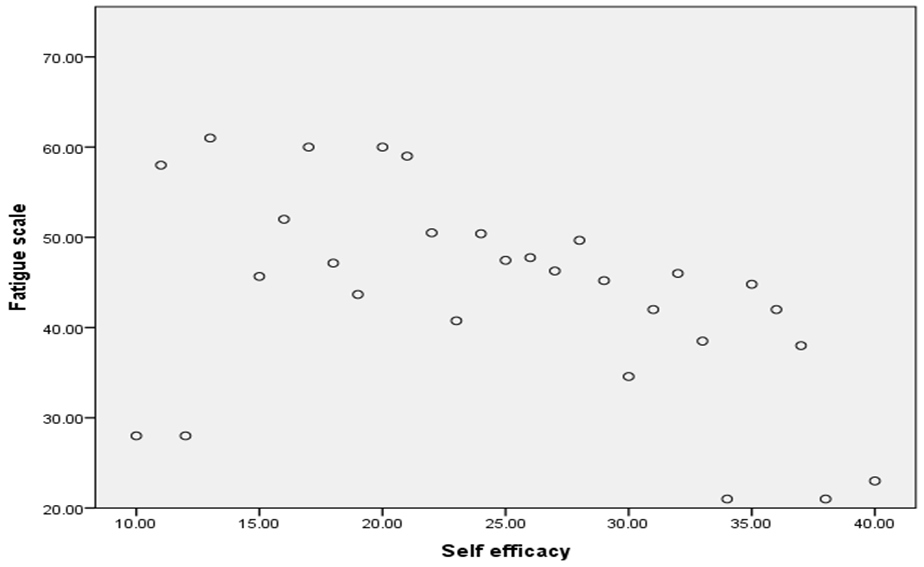

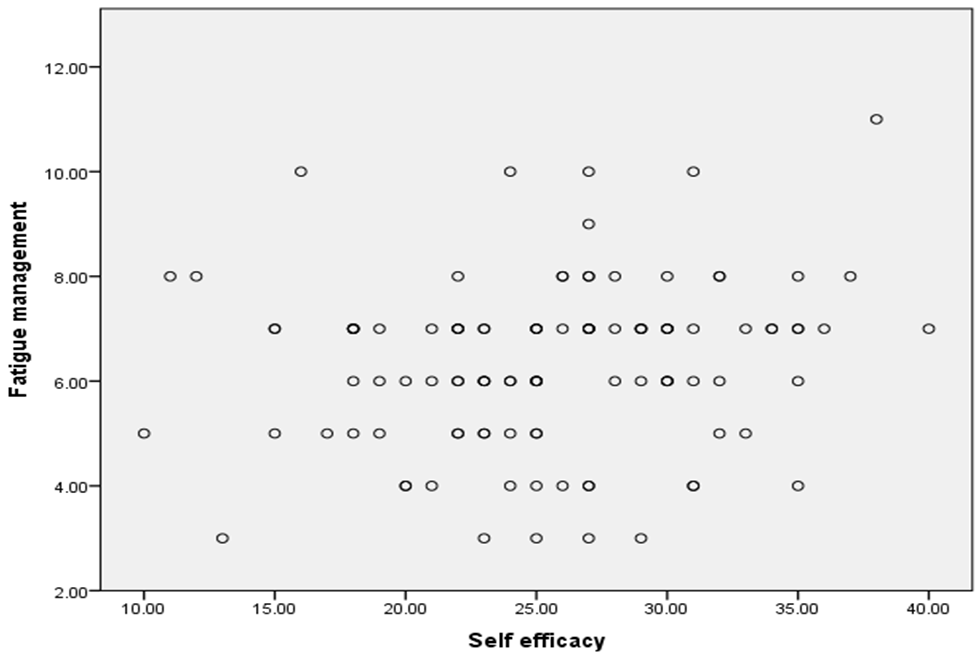

| Figure (3). Correlation between fatigue level and self-efficacy level among Hemodialysis Vs Oncology patients |

| Figure (4). Correlation between self-fatigue management and self-efficacy level among study groups |

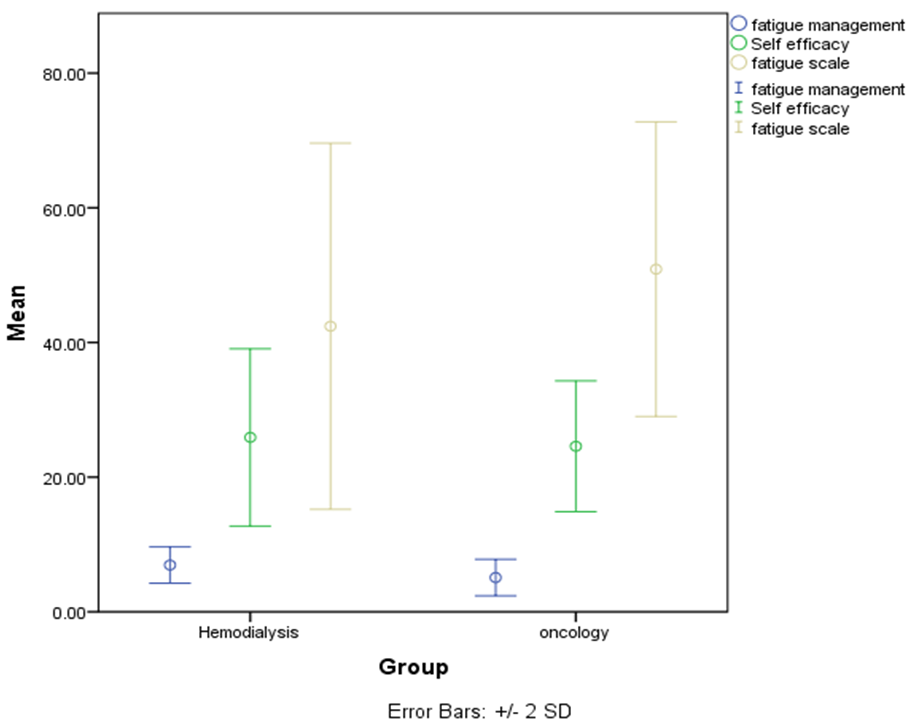

| Figure (5). Mean and Standard deviation of fatigue scale , self fatigue management and self efficacy level among the study sample |

5. Discussions

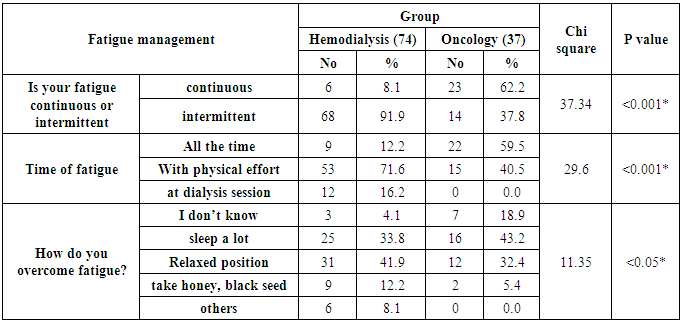

- Fatigue is one of the commonly reported complaints among oncology and hemodialysis patients. It is associated with impaired health related life style. Fatigue is documented as a negative symptom experienced by a large number of patients with end stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. It is a distressing symptom and consequences can be overwhelming [30]. The person with fatigue need more efforts to perform activities, physical and cognitive, compared with the effort required before the onset of fatigue. Individual have developed avoidance behavior, experience a sense of loss and diminished quality of life [31]. Therefore, the various treatment strategies, that is, exercise, psychosocial support, stress management, nutrition, sleep regulation, and restorative therapy provides effective means to attenuate fatigue [6].Regarding the socio demographic characteristics of the study subjects; it revealed that almost half of the hemodialysis patients; their age was between 35-59 years while two thirds of the oncology group their age was between 18-24 years old. Also it revealed that almost two thirds of the hemodialysis group were females while three quarters of the oncology patients were among males (Table 1). This finding is supported by the results achieved by [32] who have a study of "Acupressure and quality of sleep in patients with end-stage renal disease". They found that "the ESRD prevalence at higher ages". Also these findings were similar to finding of a study conducted by [33] about “Pre-tertiary hospital care of patients with chronic kidney disease in Indian”, where the majority of patients were male. Additionally, [34] who studied “Sex Disparities in Cancer Mortality and Survival “and reported that sex differences in co-morbidity at cancer diagnosis could also skew cancer survival in favor of one sex over the other. Some (45–49), but not all (50–52), studies have suggested that males have more co-morbid conditions at the point of cancer diagnosis than do females. As co-morbidities are independent prognostic indicators, pre-existing chronic conditions may contribute to poorer cancer survival could be due to the increase prevalence of cancer across the young age continuum. As regard to self-efficacy scale among Hemodialysis and Oncology patients; the current study revealed that almost half of the hemodialysis group verbated moderately or exactly true that It was easy for them to stick to their aims and accomplish their goals while more than half of the oncology group verbated that it is hardly true for the same item of the self-efficacy scale with a highly statistical significant difference P < 0.01 (Table 2). This is in line with [35] who surveyed “association of breast cancer patient’s self-efficacy with coping with cancer, perceived barriers to pain management, distress, and pain outcomes in a multiethnic”. Their Results revealed Greater self-efficacy for coping with cancer was associated with older age, less time since diagnosis, and less distress. Also [36] stated that patients on hemodialysis used coping methods “sometimes” and “seldom,” respectively, for coping with the existing conditions, and further added that coping methods were slightly helpful for patients. This is could be because both renal failure and oncology diseases considered as a chronic illness in which one’s patients passed the stage of shock and denial gradually will move into a stage of adaptation and coping.Whereas, a study titled; “The Development and Preliminary Testing of an Instrument for Assessing Fatigue self-management Outcomes in Patients with advanced cancer”. It concluded that fatigue is a prevalent symptom in advanced cancer. Support for this distressing symptom can be endorsed by understanding the complexity of components of self-management including the frequency, perceived effectiveness, and perceived self-efficacy of fatigue self-management behaviors [37]. This is supported the present study results which declared that almost half & majority of the hemodialysis and oncology group respectively verbated agree that their fatigue prevents sustained physical functioning, also more than half & majority of the hemodialysis and oncology group respectively verbated agree that fatigue interferes with their physical functioning with a statistical significant difference P < 0.01 & <0.05 respectively. As regard to fatigue interferes with carrying out certain duties and responsibilities; more than third & majority of hemodialysis and oncology group respectively verbated agree with highly statistical difference P< 0.01 (Table 3). Moreover, it reveals positive correlation as evident as when fatigue managed appropriately, self-efficacy increases=0.176 with p value >0.05 (Fig. 4). As it come to fatigue management among Hemodialysis Vs Oncology patients; the results reflect differences in responses for the nature of fatigue inherited among two groups. The statement “is your fatigue continues “revealed to be highly statistically significant with P value <0.001* in majority of hemodialysis patients, while more than half of oncology patients stated that fatigue was intermittent. In regards to time of fatigue, more than two thirds of the hemodialysis group reported that fatigues comes with physical effort while more than half of oncology patients reported from fatigue all the time with highly statistically significant with P value <0.001* (Table 4) & (Fig. 5). This is supported with a study about “Activity Pacing Self-Management in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” by [23]. The findings revealed that activity pacing self-management was effective for participants with chronic fatigue syndrome and showing that adaptive pacing alone was not effective in treating chronic fatigue syndrome. More over Activity pacing self-management uses the principle of activity pacing but incorporates a grading phase to gradually increase activity and exercise levels [38, 39]; self-management of fatigue means giving priority to certain activities that are considered essential (e.g., personal hygiene) and deferring, postponing, or delegating all those activities that are not essential (e.g., shopping). Patients may find it useful to keep a personal diary to determine which of their activities are associated with the most intense fatigue. Then, activities and related periods of rest can be planned.Moreover, for fatigue self-management; the results showed that only one third & almost half of hemodialysis and oncology group respectively stated that they are sleeping a lot as an overcoming action with a highly statistical significance P <0.05 (Table 4). This is contradicted with [40] who identified several strategies that patients may found useful for managing their own fatigue, including energy conservation techniques such as prioritizing activities, pacing (alternating physically demanding with more sedentary activities), scheduling activities at times of peak energy, taking naps as long as they do not interfere with night-time sleep and following a structured daily routine. Distraction through engaging in pleasurable activities is also recommended. This is due to the connection between sleep and chronic fatigue looks at the role of pain. The physical pain associated with chronic fatigue may be a significant factor in the sleep problems experienced by people with chronic fatigue. It has been noticed that pain and sleep influence each other in multiple ways. Pain can make sleep difficult to achieve and sustain. Lack of sleep, in turn, can make patients more sensitive to pain vice versa.Correlation between fatigue and self-efficacy scale among Hemodialysis Vs Oncology patients; resulted in evident of negative correlation between fatigue and self-efficacy as fatigue increases, self-efficacy decreases, R = - 1.88 with p value of <0.05 (Figure 3). This is supported by a study about “Association between general self-efficacy, social support, cancer-related stress and physical health-related quality of life”. They stated that general self-efficacy is considered a key factor in coping with adjustment to cancer and health related quality of life” HRQoL” [15]. More over general self-efficacy refers to a global confidence in coping abilities across a wide range of demanding situations and reflects a person’s general problem-solving ability better mental and physical health related quality of life HRQoL, increased physical functioning and increased cancer specific health related quality of life HRQoL have been demonstrated. In patients with neuro endocrine tumors, higher general self-efficacy was associated with better mental and physical health related quality of life HRQoL [41-44]. Strategies for the management of cancer-related fatigue (CRF) emphasize evidence-based strategies for reducing this common symptom. The largest body of data exists for the benefits of exercise for reducing CRF. Patient education and counseling are also considered integral to effective management of CRF. Additional interventions can be non-pharmacologic or pharmacologic, although a combination of approaches may be employed. Several factors known to be associated with CRF may be particularly amenable to treatment.

6. Conclusions

- Ÿ There is an evident of negative correlation between fatigue and self-efficacy as fatigue increases, self-efficacy decreases.Ÿ Patients on hemodialysis endure a high symptom burden that causes daily distress and negatively affects their physical activity.Ÿ Positive correlation as evident as when fatigue managed appropriately, self-efficacy increases.Ÿ There is a highly statistical significant difference regarding fatigue self -management among both groups of the present study.

7. Recommendations

- Ÿ Nurses need to assess fatigue levels routinely among patients who are either receiving chemotherapy or hemodialysis. Also nurses need to exert efforts and spend quality time with chronic fatigue patients and find means to raise self-efficacy and employ all possible means to better manage fatigue.Ÿ Clinical research on cancer-related fatigue should focus on an improved understanding of the etiology of fatigue, relationships between fatigue and co-occurring symptoms, and evaluating treatment interventions.Ÿ Well-designed clinical trials are urgently needed for the development of empirically supported fatigue management strategies to reduce the symptom burden associated with cancer.Ÿ With growing interest in chronic illness, recognition of fatigue as a prioritizing issue for researcher’s grants, and treatment guideline development for clinicians to create. Oncologists, and oncology nurses as well as the entire medical team, should become more aware of fatigue problem, its impact on patient quality of life, and the various strategies that may be helpful in its management.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML