-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2017; 7(1): 1-15

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20170701.01

Capacity Building for Nurses’ Knowledge and Practice Regarding Prevention of Diabetic Foot Complications

Wafaa H. Abdullah1, Samira Al Senany2, Hanaa Khaled Al-Otheimin3

1Assistant Professor, Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Menoufia University, Egypt

2Assistant Professor in Gerntology, Public Health Departemnt, Faculty of Nursing, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA

3Supervisor in Public Health, Regional Nursing Directorate, Al-Madina Al-Mounawara, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Wafaa H. Abdullah, Assistant Professor, Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Menoufia University, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Diabetic foot ulcers are a complication affecting approximately 15% of the total population with diabetes mellitus. There are three and half million diabetic patients in Saudi Arabia alone. Aim: to determine capacity building for nurses’ knowledge and practice regarding prevention of diabetic foot complications. Research Questions: 1. Does the nurse’s knowledge prevent diabetic foot ulcer and other foot complications? 2. Does the high practice of the nurses during foot screening can prevent diabetic foot ulcer in primary health care centers in Saudi Arabia? Design: Descriptive, research designs have been utilized. Setting: Chronic disease clinic in primary health care centers in Jeddah city. Subjects: a purposive sample of 30 nurses and convenience sample of 30 patients. Tools: A. Diabetic foot ulcer Structured interview questionnaire to assess nurse’s knowledge regarding diabetes mellitus and diabetic foot. B. Health status assessment questionnaire to assess health history status of diabetic client. C. An observational checklist to assess the nurse practice once during diabetic foot screening. Results: Significant increase in nurse's knowledge had been observed, while the majority of them had poor practice in relation to foot screening. Whereas complicated diabetic patients represent 35.7% of diabetic patients have neuropathy. Moreover, only 7.1% have neuropathy and diabetic ketoacidosis. Also there was a significant moderate positive correlation between the overall score of nurse’s knowledge and the overall score of the practice regarding diabetic foot complications. Conclusions: Proper foot care, early recognition and management of risk factors prevent foot ulcer. Recommendations: Developing a structured training educational program for nurses dealing patients with diabetic foot disorders.

Keywords: Nurses knowledge & Practice, Primary health care center, Diabetic foot complications

Cite this paper: Wafaa H. Abdullah, Samira Al Senany, Hanaa Khaled Al-Otheimin, Capacity Building for Nurses’ Knowledge and Practice Regarding Prevention of Diabetic Foot Complications, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2017, pp. 1-15. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20170701.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Diabetes is the “mother” of all disease and it is the third main reason of death globally [1]. The economic cost of diabetes and its related complications are abnormally high and moreover the human cost must be considered. Diabetes causes that were studied in Turku reported that one death occurs every 10 seconds and one amputation every 30 seconds [2]. Therefore, the effect of Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is significant not only on the diabetic patients but also on their families and the whole society [3]. The major categorizations of Diabetes Mellitus (DM) are type I diabetes, type II diabetes, gestational diabetes, and DM linked with other conditions or syndromes [4]. At national level, in Juvenile Diabetes or type I diabetes, there was a significant increase in childhood obesity, and results in insulin resistance [2].In Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) there are major influences on Saudis’ health-related behaviors such as financial growth, modernization and globalization, although critically, several researches have revealed that, nationally, the overall rate of inactivity in various age groups and genders vary from 43.3% to 99.5% [5]. Some factors that give rise to type II diabetes mellitus are obesity, sedentary habits, and inadequate diet [6] and obesity has increased among children as well as among Saudi adults. It is evident that, Type II DM, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia have grown significantly in recent years [5].The main goal of all management planning for diabetic patients is prevention of both short and long term complications [7]. A study found that between 49-85% of all amputations can be prevented by adopting well-structured preventive management for example; healthy diet, physical activity, the prevention of overweight & obesity, and stopping smoking [8]. Nutritional aspects play an important part in the management of DM. In more than 50% of diabetic patients presenting with limitation of energy intake, increased activity and weight reduction can normalize blood glucose level, while medication is likely to be needed later [9]. Lifestyle changes and nutritional modification that aimed to be low in calorie intake, low- fat, low-saturated fat, high-fiber diet and moderate-intensity physical activity of at least 150 minutes per week can result in a 5% reduction in initial body weight and post four years; the diabetic risk declines to 58%. The studies contain comprehensive, continued programs to reach the outcomes [3].Physical activity is a vital part of diabetic management. Regular exercise has been shown to normalize blood glucose level, reduce cardiovascular disease CVD risk factors, enhance weight loss, and improve well-being [10]. In general, the goals of diabetic management are to improve the quality of patients’ lives, to avoid premature death, and, macro or micro complications [9]. Smoking is significantly linked with critical complications among diabetic patients however quitting smoking is not given a lot of importance in the majority of diabetic clinic and has yet to become part of diabetes counseling sessions. Other studies have proven that cigarette smoking, whether active or passive, is an independent adjustable risk factor for the development of DM and its complications [11]. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy is the most common diabetic complication, accounting for substantial morbidity and mortality and leads to vast healthcare funding [12]. Lifestyle modifications can lower the risk of DM and also have other positive health benefits. The health care team should keep in mind that any prevention must be delivered in a culturally sensitive way [3]. The management of Diabetic foot complications (DFCs) can be optimized by using an interdisciplinary team that focuses on the correctable risk factors along with optimizing local wound care [13]. There are five cornerstones of diabetic foot management; regular inspection and examination of the at-risk foot, identification of the patient's at-risk for Diabetic foot complications, education of patient, family, & healthcare providers, appropriate footwear and treatment of non-ulcerative pathology [14].Diabetic foot assessment by an inter-professional team must be an integral part of diabetic management to determine patients at risk for Diabetic foot complications [3].Nurses evoke the sense of association between acute complications and the value of preventative action and maintenance through bridging with this basics knowledge through education [15]. The purpose of diabetic education is to offer knowledge and skills that assist patients to detect obstacles, and aid problem-solving and coping skills, to accomplish valuable and modifiable self-care behavior. Furthermore, a DM education plan, including “survival skill” education and a follow-up plan should be developed for each hospitalized diabetic client [16]. The health professional educator should demonstrate skills, such as how to cut nails correctly. The educational sessions must be given over time and on more than one occasion, preferably using combined methods. [17]. Practical and community based studies have demonstrated intensified prevention strategies including client education, assessment and identification of risky foot, implementing of preventive measures such as proper footwear and inter-disciplinary management can decrease by almost 50% the amputation rate in diabetic patients [18].Recent advances in basic science research and related techniques have influenced the options for the treatment of chronic wounds. A study concluded that if Diabetic foot complications (DFCs) are not 50% smaller at week 4 although optimal care, by week 12 it is unlikely to heal. An earlier decision to use advanced therapies improves the likelihood that these interventions will be effective. Several studies have shown that advanced biologic therapies, in combination with standard care, improve the healing of DFCs [13].Diabetic education is the key for prevention [19]. Nurses have a specialist responsibility to seek evidence-based with the power of diabetic practice to expand educational foundations and maintain a knowledge base, accessible and precise, in addition to promote competent self-care. Many diabetic patients are inadequately educated about caring for their limbs and must be aware of their risk factors and how to manage them [19]. Essential elements in diabetic preventive care are the patients' knowledge and awareness of DM and later, self-care which is aimed at client empowerment through nurse’s knowledge and education [15]. All patients with peripheral neuropathy must wear suitable footwear and assess their limbs every day to detect any changes early [10].In Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) diabetes mellitus care is mostly integrated into the community health system primarily through primary health care PHC centers. The diabetic patients are referred from PHC centers to specialist diabetic centers. There are two reasons for this. First, PHC interventions aim to manage diabetic patient’s starting's with the registration of the patients in a PHC center and the issuing of DM card. Medical diagnosis includes a physical examination and laboratory studies. Additionally, to medical treatment, management includes client education using the Diabetes Patient`s Education Checklist [20].To achieve optimal care of diabetes an interdisciplinary team expert, personnel is required, and the PHC system needs to allow and support sharing and collaboration between primary care and specialist care as needed [3]. The diabetic foot specialist nurse is the corner stone of this team, who involved in examining and educating patients; this strategy will have a greater impact on prevention of foot ulcers and amputations in future. A program at regional level and national level is required for the awareness of diabetes and its complications especially in foot complications and its prevention [21].A deficiency of DM knowledge among interdisciplinary team has contributed to diabetic patients getting inadequate instruction in PHC. Identification the nurse’s knowledge of DM and its management is vital for the safety of the client as well as for the projection of macro complications [3].Capacity building is defined as promoting an environment that increases the potential of individuals, organisations and communities to receive and possess knowledge and skills as well as to become qualified in planning, developing, implementing and sustaining health-related activities according to changing or emerging needs [22].Significance of the study:Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases [23]. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) was listed as having the 6th highest prevalence of diabetes globally [24]. Diabetes mellitus is a chronic debilitating medical condition which affects at least one in five Saudis i.e. there are three and half million of DM patients in Saudi Arabia [25]. Other gulf countries listed in the top ten include Bahrain with 19.9%, Kuwait 21.1%, and the United Arab Emirates 19.2% [26]. The prevalence of diabetes in (KSA) is rising, reaching a disturbing figure of 23.7% [25]. Jeddah is the second largest city in (KSA), with a total population exceeding 4 million people [27]. The annual incidence of diabetes was 3.1% as reported in a single study. Approximately 10,788 patients with (DM) are likely to develop diabetic foot ulcer each year in Jeddah [28]. It is estimated that 24.4% of the total health care expenditure for diabetic patients is related to foot complications [29].

2. Aim of the Study

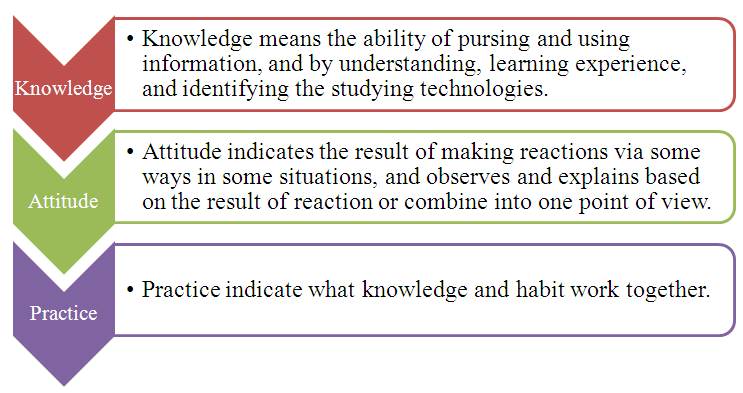

- Aim of the study was to determine capacity building for nurses’ knowledge and practice regarding prevention of diabetic foot complications.Research Questions:1. Does the nurse’s knowledge illustrate education role in preventing diabetic foot ulcer and other diabetic complications?2. Does the nurse's practice in foot screening would detect foot ulcer among diabetic patients?Operational definition:Indicators for Diabetic foot ulcer complications are infection, scarring, with or without deep tissue damage.Conceptual framework: The nursing conceptual framework of this study was based upon human caring theory which provides a framework for understanding the relationship of caring for the client and nurse through particular experience & values, quality, meaning, and soul- to-soul human phenomena that allows an integral view of the whole [30]. A conceptual framework directed approach to patients, and health care modification illuminates the need for significant changes to happen [31]. Watson's theory includes the Transpersonal Caring Occasion with 10 "caritas" that are the guiding principles of this theory. Interchangeably terms have been utilized such as the human being, personhood, life, self and client. Watson considers client as a union of mind, body, nature, and spirit, and in addition she described personhood as one’s spirit having a body that is not limited by objective, space and time [32].The other conceptual framework of this study was based on the knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) model and literature review related to prevention of diabetic foot complication for patients with diabetes. The KAP model was used in the 1950s in the field of family planning and population studies [33]. The KAP is an illustrative study performed on a specific population to determine the knowledge (K), attitudes (A) and practices (P) of a people on a particular subject [34]. Knowledge and practice (skill) are necessary for diabetes care. Knowledge helps the patients to recall and enhance understanding level of diseases DM, so, knowledge and practice were examined in this study for prevention of diabetic foot ulcer DFCs [6].According to the KAP Model, knowledge, attitude, and practice in this study are the main concepts representing nurses’ caring role to prevent DFCs; the three concepts are integrated as the following [35].

| Figure 1. The influence diagram of knowledge, attitude, and practice [36] |

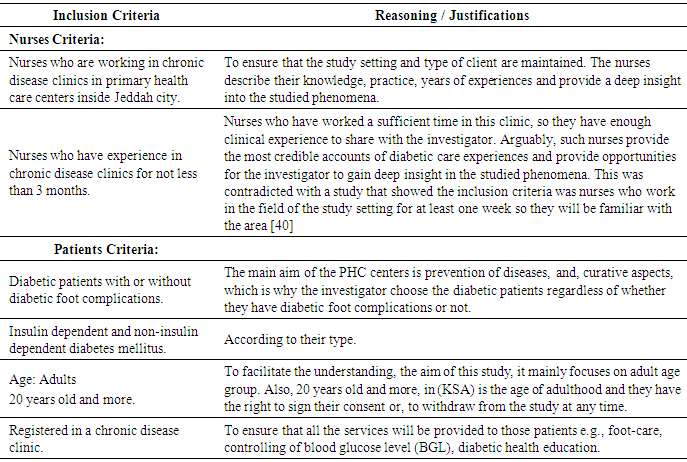

3. Subjects and Method

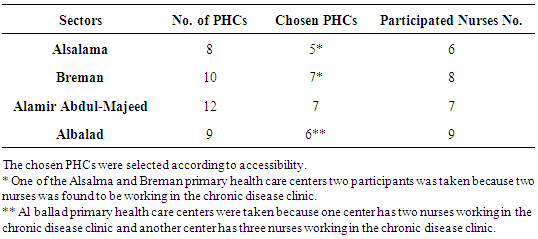

- Research Design:A quantitative, descriptive research design was used in this study. Setting:The study was carried out in Jeddah the second largest city after Riyadh the capital of Saudi Arabia. Jeddah considered as the mainland, sea and air gateway for pilgrims going to the two Holy Mosques in Makkah and Medina [37]. Jeddah has a population exceeding 4 million people [6] from diverse cultural backgrounds and ethnicities [37].There are thirty-nine centers inside Jeddah city with a total of 22,000 diabetic patients registered, and regularly visiting, these centers [24]. The main governmental agency, bearings the primary responsibility for the Kingdom’s provision of preventive, curative and rehabilitative services, is the MOH [5]. This study conducted in PHC centers within Jeddah city and was divided into four sectors: Alsalama, Breman, Alamir Abdul-Majeed and Albalad. The investigator chooses all the sectors inside Jeddah city.

| Table 1. The sectors inside Jeddah city |

|

4. Results

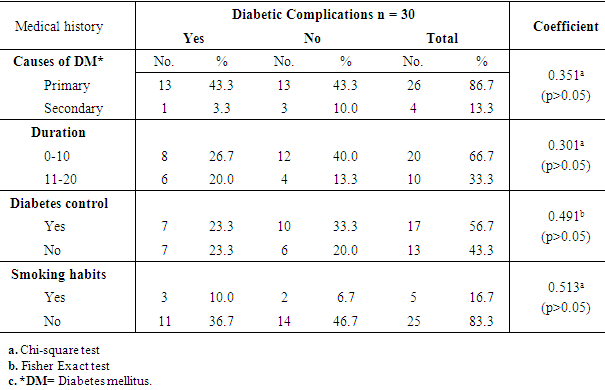

- Table (3) showed the relationships between medical history and diabetic complications among diabetic patients. Whether the patients had diabetic complications or not, the study result shows that 43.3% of patients had primary cause of DM. Regarding smoking habits, it was found that 83.3% did not smoke. While, only 16.7% had smoking habits with no statistical significant differences P= 0.513.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

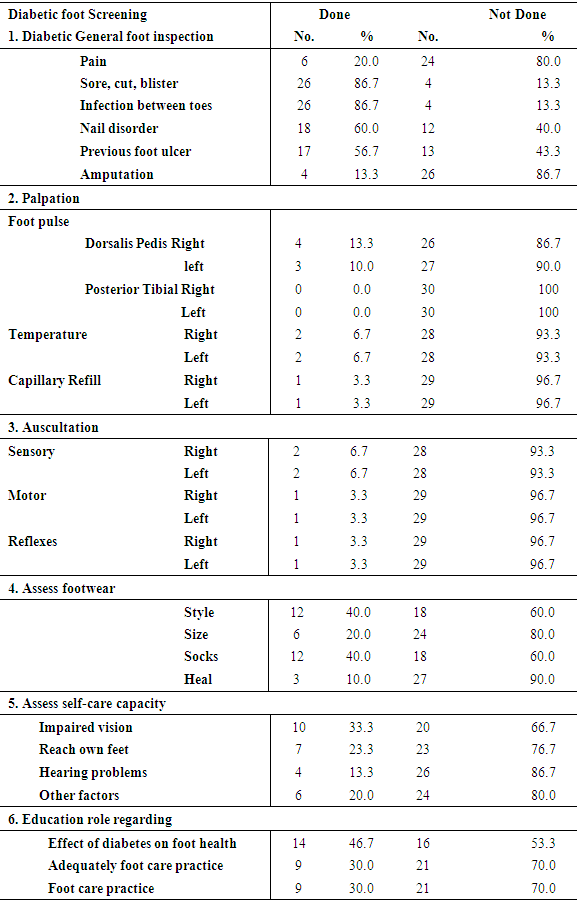

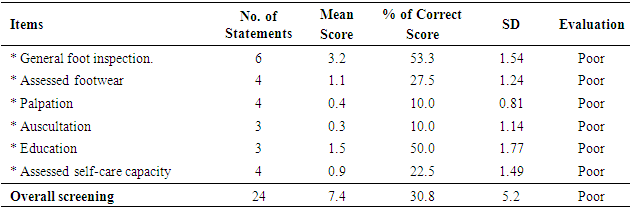

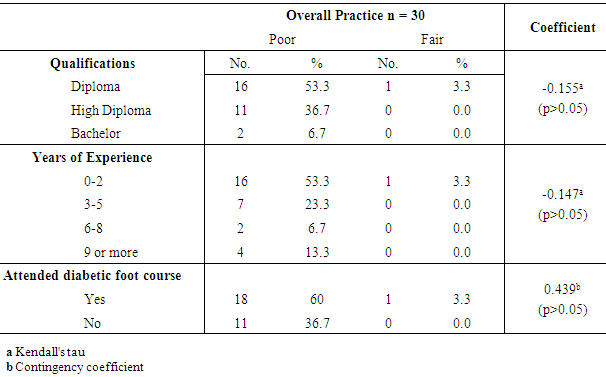

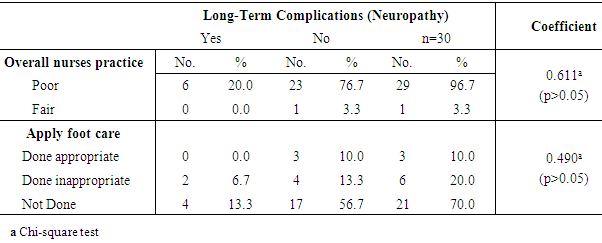

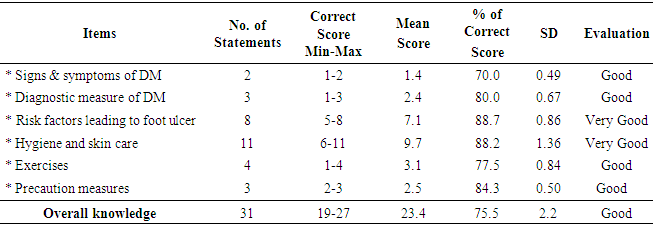

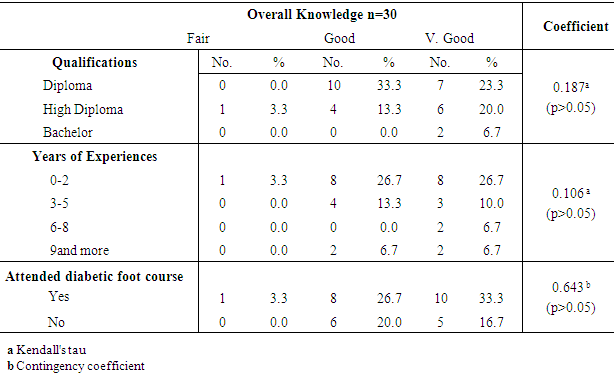

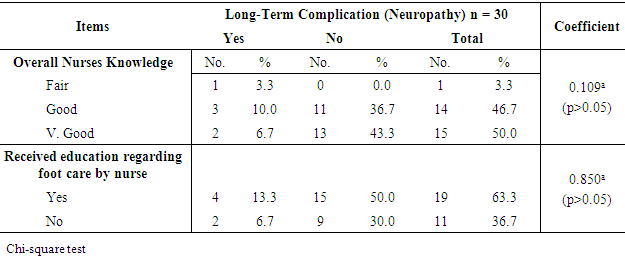

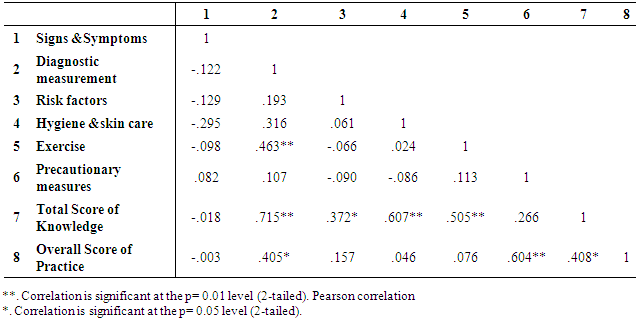

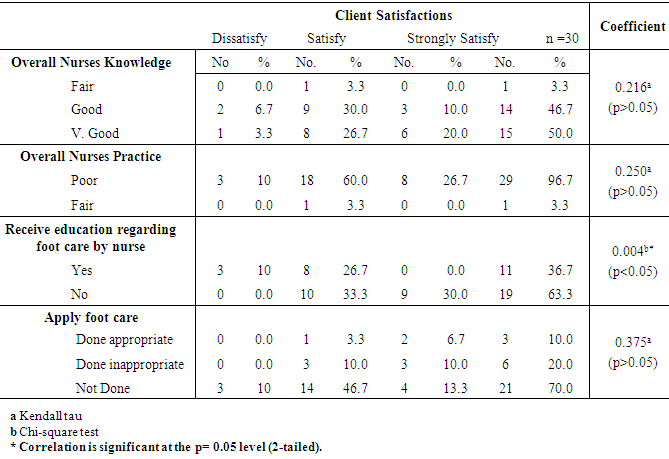

- Somewhere in the world every 20 seconds as a consequence of Diabetic Foot Complications a lower extremity is lost [2]. Diabetic foot complications and its associated morbidity and mortality have become a critical global burden, but it is preventable. It has been reported that the risk for diabetic patients to develop diabetic foot complications could be as high as 25% in their lifetime [43]. So, the overall aim of the study was to determine capacity building for nurses’ knowledge and practice regarding prevention of diabetic foot complications.The findings of the existing study revealed that the nurses who participated have good knowledge, but that they had poor practice regarding prevention of diabetic foot complications. Also, there is a positive relationship between the nurse's total score of the knowledge and practice at significant level 0.05. The discussion of the study results presented according to the research questions. Part One: (RQ 1): Skilled diabetic nurses play a vital role in the management of diabetic foot complications, such as educating and encouraging diabetic patients to participate in proper foot care, foot screening, and testing for signs and symptoms of diabetic foot complications [44].Regarding the relationships between patient`s sociodemographic characteristics as age, durations of diabetes, occupations, educational level, and marital status in correlation with diabetic complications, there was no statistical significant difference had been found among them (Table 3). This findings was not supported by other studies under the title of “The Assessment of Relations between Socioeconomic Status and Number of Complications among Type II Diabetic Patients” variables such as age, duration of diabetes, educational level, and occupations of 530 patients as all showed significant relations with number of diabetic complications among study population (P<0.001) but in relation to marital status there was no statistical significance difference, however, it was supported with the present study [45].Medical history of the participating patients as; incidence, diabetic control and smoking with diabetic complications; revealed that there was no statistical significant difference had been found (Table 3), while another study of the assessment of diabetes-related knowledge among nursing staff in a hospital setting” stated that there was contradiction in the view that tighter diabetic glycemic control has been linked with decline in complications, infections, length of stay, morbidity and mortality in a various of medical settings [46]. Also, a further study about Smoking and diabetes stated that multi surveys of smoker patients with history of DM consistently found a heightened risk of morbidity and premature death linked with the occurrence of macrovascular complications [47]. The Baqai Institute of Diabetology and Endocrinology which studied Diabetic Foot Care - A Public Health Problem concluded that lack of awareness, uncontrolled blood glucose level (BGL), and duration of DM was the main factors leading to diabetic foot complications [48].The present findings stated that their overall nurse’s knowledge score was very good regarding prevention of foot ulcer through hygiene and skin care (Table 8), also 33.3% of the nurses who attend diabetic foot courses had a very good overall knowledge regarding preventing of diabetic foot complications (Table 9). This is contradicted with [49] who studied “determining registered nurses’ knowledge of diabetes mellitus”. They reported that all nurse’s responses were correct 100% on foot care. Although nurses knew that patients with diabetes had problems with their feet. This may be attributed to the way of assessing the nurse’s knowledge could be in different manners. The overall nurse’s knowledge was good level and at the same time they had attended diabetic foot courses and their clinical experience was less than two years (26.7% & 26.7%) respectively (Table 9). This result differed from [50], who studied a Survey of Nurses’ Knowledge Regarding Prevention and Management of Diabetic Foot Ulcer concluded that there was no subject in the survey who had attended any courses or training programs related to prevention and management of diabetic foot ulcer. This defect in staff development or training can lead to gaps between knowledge and practice, which affect the quality of care.The research findings also found that the bachelor and diploma nurses had very good knowledge; also, for nearly one-third of the studied sample, their overall knowledge varied between good and very good and they had less than two years' experience (Table 9). This result contradicts with [46] who studied “Assessment of diabetes-related knowledge among nursing staff in a hospital setting” and determined that the level of nurse's knowledge was significantly higher in nurses with higher qualifications (bachelor's degree) when compared with diploma nurses. Also, the present result findings are contradicting with the same study [46] which reported that nurses with extended experience in their work and those with a higher degree of qualification showed a more advanced level of knowledge than their counterparts. However, the positive impact of extended experience in nurses with a diploma degree was not seen in those with the higher degree of qualifications. This could be due to retention time spans, as like a recently graduated nurse, they still keep their knowledge as long as their years of experience.The present findings revealed that there were no statistical differences with patients who received education regarding foot care by the nurse and the presence of the neuropathy (Table 10). This result is supported with [51] who studied “the Influence of diabetes related knowledge on foot ulceration”. It revealed that the diabetic patient’s knowledge with foot ulcer & those with no history of foot ulcer, and among all of them there is no statistical significant difference. Whereas [52] results were contradicted with the present study results who studied “An Assessment of The Level of Knowledge of Diabetic and Primary Health Care Providers in a Primary Health Care Setting, on Diabetes Mellitus". They reported that the mean knowledge score (6.5 out of a possible 11) there was a possible correlation between the score and having received advice on foot care (6.9 vs. 5.4, P=0.001). This can be attributed to receiving an educational program regarding foot care that have been carried out for the diabetic patients in chronic disease clinics. Part two: (RQ 2):Foot screenings, including assessment of neuropathy, appropriate foot care education and management were all the main risk factors linked with DFCs. Peripheral vascular disease and neuropathy assessment are important trends in diabetic foot ulcer complications and lower extremity amputations, particularly in those at high risk. Diabetic patients receiving foot screenings were significantly more likely to get education on foot care and prevention in comparison with patients who did not have their foot examined [53].The present findings revealed that the nurse’s practice regarding overall screening was a poor level (Table 5). This finding was contradicted by a study carried out about Foot examinations of diabetes patients by primary health care nurses in Auckland, New Zealand. It concluded that one third of 265 patients, confirmed that nurses routinely examine diabetic patient’s feet, while nearly half of patients had their feet examined [53]. Nurses emphasized that the reasons for their low practice could be interpreted as work overload, their views about screening of diabetic foot was not included in their job descriptions, and consider it as the physicians' role at consequently and refusing it (foot screening) as well. The present findings revealed that the participated nurses have lowest percentage score on auscultation and palpation during diabetic foot screening. Also, minority of them had a fair overall practice, and they had less than two years' experience (recently graduated). While the highest percentage scores of their practice was in general foot inspection such as; sore, cut, blister, and infection between toes (Table 4, 5 & 6). This was not supported with a studied titled “An Assessment of The Level of Knowledge of Diabetic and Primary Health Care Providers in a Primary Health Care Setting, on Diabetes Mellitus. It mentioned that annual foot screening for diabetic patients, the identification of patients to receive advanced foot care and education were given to all patients with DM [52]. While, [53] carried out study about Foot examinations of diabetes patients by primary health care nurses in Auckland, New Zealand. It illustrated that the patients consulted by district nurses were significantly more likely to have their feet examined for color, skin integrity and nail-beds compared with patients consulted by specialist nurses and practice nurses. The nurses in PHC centers had annual formative training courses regarding chronic disease as DM in general. That is why they should be a diabetic specialist nurse; where their works were focuses on preventive and curative aspects regarding DM and its complications.The present study found that less than half of the participating nurses provided the footwear assessment and patient's education (Table 5). Specialist nurses were more likely to carry out foot screenings that included palpation of pedal pulses, microfilament sensation testing and checking for edema, compared with the care that patient's consulted by both practice nurses and district nurses received (p<0.05) [53]. Footwear is a common cause of foot ulcer complication especially in diabetic patients with sensory neuropathy [54]. The intensive prevention strategy including patient's education, foot care practice, and appropriate footwear can save costs if the risk for lower limb ulcers and foot amputations can be decreased by 25% [55]. As foot wear are common causes of DFCs as neuropathy among diabetic patients. The PHC nurse may have to be more educated regarding foot wear assessment and foot care in general which would decrease the incidence of DFCs resulting in foot amputation.More than half of the nurses who have less clinical years of experiences had a poor score in overall practice. Also, despite some having more experience, nurses had same level of practice with no statistical significant differences (P=0.147). Although more than half of the nurses had attended a diabetic foot course, the current study showed that they still had poor practice with no statistical significant differences (P=0.439) (Table 6). This is supported by a study which illustrate that the specific diabetic education and experience in existing practice were not linked with nurses who frequently did diabetic foot screenings or provided foot care consultations [53]. The inability of the health care providers such as primary health care nurses to maintain knowledge and practice is a major concern in this challenging complication DFCs.Nurses' overall practice was poor, and nearly a quarter of the studied patients had diabetic neuropathy complications. Regarding the identification of appropriate application of foot care, for most of patients this was not done while for a minority of the patients it was done in-appropriate with no statistical significance differences in both (Table 7). Another study showed that no relationship was found among nurses who had identified foot ulcers as complications or neuropathy, and those who did screening of the diabetic foot [53].The present findings which ascertained that half of the diabetic patients, who received education regarding foot care by a nurse, had no neuropathy as diabetic complications. Although the study also found that more than half of the diabetic patients did not apply foot care and had no diabetic neuropathy complications, with no statistical significant differences (P=0.490) (Table 7 & 10) respectively. This is in line with a study done to assess the foot care practices of 61 diabetic patients all of whom had received foot care educations. While, improper foot care was evident in those who already had foot ulcers as well as in those who were at high risk. Also it was found that a significant reason behind lack of proper foot care was deficiency of provision of foot care education [48].Regarding to overall nurse's knowledge and practice; the present findings confirmed that there was a significant moderate positive relationship between the overall knowledge and the overall practice of the nurses regarding prevention of diabetic foot complication at significant level 0.05 which indicates that as the knowledge increases the practice of the nurses also increases (Table 11). This is not in line with [56] who have a study of Bridging the knowledge–action gap in diabetes: information technologies, physician incentives and consumer incentives converge. It revealed that the gap between diabetic knowledge and its application in diabetes care is apparent. Although research over the last decade has shown that adherence to standards of care can prevent or delay the onset of devastating diabetic complications whereas another study of bridging the gap between knowledge and practice. It mentioned that there is a gap between theoretical knowledge and its application in practice which is a point frequently discussed in the nursing press. In order to be effective, healthcare education must result in improved care and practice [57]. As nurses play a key role in promoting higher standards of health and client care. They should be updated with current knowledge and practice in their field. In addition, diabetic specialist nurses more specialized in the care and management of patients with diabetes which can prevent the devastating complications.The present study result showed that with the nurses who have a fair in total knowledge and practice; only minority of their patients were satisfied. While, another minority of the nurses having very good in their overall knowledge, and none of them with fair overall practice, their patients were dissatisfied from nurse’s practice with no statistical significant difference (P=0.21, P=0.250). About quarter of the patients who received education on how to care for their feet by the nurse were satisfied with statistical significant differences (P = 0.004) (Table 12). This is congruent with a study done about Quality of primary health care in Saudi Arabia: a comprehensive review. The results reported that the patients are moderately satisfied with, listening, nurse’s education and physician explanation and they were dissatisfied with poor communication and exchange of information or education between patients and health care providers, including physicians, nurses, and pharmacists [58].PHC centers are the first level of professional contact in the community and form the corner-stone strategy for the achievement of health level that will allow socially and economically productive life [59]. Foot care education and regular foot screening are strategies for prevention of foot ulcers and those preventive practices must be reinforced so that the patients without foot ulcers will not develop ulcers [48].The nurses who participated in this study have good knowledge but poor practice (Table 5 & 8). Diabetic foot complications are the major reason for hospitalization in DM patients and are one of the health system concerns. Although, nurses as part of the diabetic care team, not only need to play their role in health care, community education, health system management, client care and improving quality of life, but also must attend particular training programs to use the updated instructions for Diabetic foot complications care in order to offer effective services to assist and promote diabetic patients’ health [60]. When the nurses have adequate knowledge, they will be able to educate and coach their diabetic patients to prevent and deal with their complications more effectively [50]. This emphasizes the core role of nurses as they are pivotal members of the diabetic team.Limitations of sample size: Due to limited number of PHC centers inside Jeddah and some of the participated nurses were uncooperative during data collection.

6. Conclusions

- v The nurse’s knowledge affects positively in patient's education and reflects on prevention of diabetic foot complication with no statistical significant difference among them.v The highly educational level has a negative impact on nurses` practice.v As long as the diabetic patients caring for themselves and they received diabetic foot education by the nurse, half of them didn't develop neuropathy as a long term diabetic complication.v There is a significant moderate positive relationship between the total score of the knowledge and the total practice score of the nurses regarding diabetic foot complications.

7. Recommendations

- Ÿ Nursing Practice: Building a periodic nurse training programs regarding diabetic foot care to be licensed and certified as diabetic nurse specialist.Ÿ Nursing administrations and health policies: Encourage governmental policy makers and other decision makers in the Saudi community to support foot care programs in each primary health care center and formulate national treatment policies in order to prevent the foot ulcer. Ÿ Patients Education:v Patients` should be educated about foot care so that they become active members of their diabetes care team instead of being passive recipients.v Develop and apply a foot care guidelines or protocol for diabetic client in PHC centers.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML