-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2016; 6(5): 109-116

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20160605.01

Leadership, Management and Team Competencies of Filipino Nursing Student Manager-Leaders: Implications on Nursing Education

Romeo Luis A. Macabasag1, 2, 3, Kathleen Kirby A. Albiento1, 3, Dianne Eraphie A. Tabo-on3, Mark Joseph D. R. Barceñas1, 3, Charmaine Anne E. Batongbacal1, 3, Diana Marie C. Bonion1, 3, Relmsley B. Geloryao1, 3, Caradel T. Idea1, 3, Jewel S. F. Saludo1, 3, Dean Jerald P. Villaverde1, 3, Kathleen Joy I. Ropero1, 3, Patrick Joshua C. Pascual1, 3

1College of Nursing, Our Lady of Fatima University, Antipolo City, Philippines

2Graduate School, Our Lady of Fatima University, Valenzuela City, Philippines

3Research Development and Innovation Center, Our Lady of Fatima University, Valenzuela City, Philippines

Correspondence to: Romeo Luis A. Macabasag, College of Nursing, Our Lady of Fatima University, Antipolo City, Philippines.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Objective: This research described and examined significant difference in the leadership, management and team competencies of student manager-leaders. Methods: This study used survey questionnaire to gather data, and was described using weighted mean. Significant difference was tested using Krukal-Wallis test and Welch’s ANOVA. Results: Findings of the study suggests strong agreement between the evaluation made by student manager-leaders (4.62) and clinical instructors (4.64), while moderate agreement was observed from student subordinates (4.17). A significant difference was also observed in the parameters of workforce planning, work environment and leadership. Conclusions: This research emphasizes the need to create conducive learning environment and innovative teaching methods to instill theoretical and practical concepts of leadership, management and team work. Data collected and analyzed have been helpful in describing the variables, but there are obvious methodological limitations in this study, hence it yields low generalization of results. Methodological suggestions were provided to address the limitations identified.

Keywords: Nursing Students, Leadership, Management, Teamwork, Competency

Cite this paper: Romeo Luis A. Macabasag, Kathleen Kirby A. Albiento, Dianne Eraphie A. Tabo-on, Mark Joseph D. R. Barceñas, Charmaine Anne E. Batongbacal, Diana Marie C. Bonion, Relmsley B. Geloryao, Caradel T. Idea, Jewel S. F. Saludo, Dean Jerald P. Villaverde, Kathleen Joy I. Ropero, Patrick Joshua C. Pascual, Leadership, Management and Team Competencies of Filipino Nursing Student Manager-Leaders: Implications on Nursing Education, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 6 No. 5, 2016, pp. 109-116. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20160605.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Competence is commonly used in the field of nursing education [1] in spite of the difficulties in defining and measuring the said concept [2]. Available literature defines competence as one’s ability and functional adequacy to assimilate knowledge, skills, values and attitudes in various context of one’s practice [3], thus competence can be seen as a combination of different attributes, attitudes and abilities that supports practice [4].Leadership, management and teamwork competencies of nurses are seen as one of the areas of competent nurses [5]. Terms such as administration, leadership, and management are commonly used interchangeably, though they are actually not synonymous [6]. Leadership chiefly centres on human relationship – focused on helping people, who are part of an organization – to achieve one shared vision. On the other hand, management aims to maintain order in the organization, through planning, organizing, coordinating and maintaining rules and regulations [7]. Although the two latter concepts are different, a review shows that out of 894 articles addressing leadership and management, 862 studies show large intersection of leadership and management competencies, indicating lack of discrimination and strong commonalities between the two concepts. In addition, team competencies closely relates with the concept of leadership and management. In fact, the latter review shows that aside from the predominant theme of leadership and management, teamwork and collaboration were mentioned several times [8]. Collaboration and teamwork is defined as the capacity to create collaborative relationship among colleagues – facilitating efficient communication between members of the healthcare team [9].In the Philippines, the current curriculum for Bachelor of Science in Nursing is guided by the Core Competency Standards for Nursing Practice, which serves as a unifying framework for nursing practice, regulation and education. The core competency areas include Safe and Quality Nursing Care, Management of Environment and Resources, Health Education, Legal Responsibility, Ethico-moral Responsibility, Personal and Professional Development, Quality Improvement, Research, Record Management, Communication, and Collaboration and Teamwork [10]. Though not explicitly stated in the 11 core competency standards, leadership, management and team competencies (LMTC) of nursing students is considered as necessary competency area. In fact, a study in Europe identified leadership, management and teamwork, among others, as one of the competency area that nursing students have to develop [5]. LMTC includes making effective decisions, leading the workforce [11], delegating and managing delivery of nursing care to various recipients [12], and facilitating teamwork and collaboration with different members of the healthcare team [13]. Attempts were made in the Philippines to explore competencies of nursing student, however most of the study focused on the general core competencies [14, 15], caring competencies [16], and leadership competencies alone [17]. In response, this study was conducted to determine the LMTC of student manager-leaders. Specifically, this study aims to: (a) describe the LMTC of student manager-leaders as evaluated by themselves, their student subordinate and their clinical instructors and, (b) examine significant difference in the evaluation of the three groups.

2. Method

2.1. Research Design

- This study used a descriptive, cross-sectional design to describe the variables pertaining to the LMTC of student manager-leaders. A survey was designed to obtain describe and examine difference of among the variables collected from 2012-2013, without establishing causation.

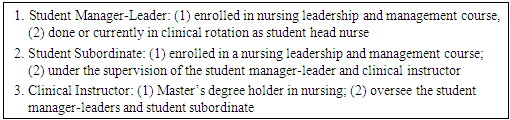

2.2. Participants

- The respondents of this research were composed of three groups namely, the student manager-leaders, student subordinates and clinical instructors. At the time of the data collection, the respondents were currently having their clinical rotation in a tertiary hospital in Quezon City, Philippines. Part of the nursing course “Leadership and Management” is to act as head nurses themselves as their practicum – thus those students acting as head nurses were operationally classified in this study as “student manager-leaders”. In the same way, other nursing students served as subordinates, while the clinical instructors acted as the supervisors. Participants were chosen using a non-randomized purposive sampling, which is based on the assumption that the researcher has enough knowledge about the participants fit for the study [18]. 15 student manager-leaders, two (2) clinical instructors, and 75 student subordinates were chosen as study participants. One of the clinical instructors evaluated eight (8) student manager-leaders, while the other one evaluated seven (7). In totality, this study collated 105 evaluations. All of the respondents participated voluntarily and was chosen based on a predetermined criteria set in this study (see Box 1).

|

2.3. Research Instrument

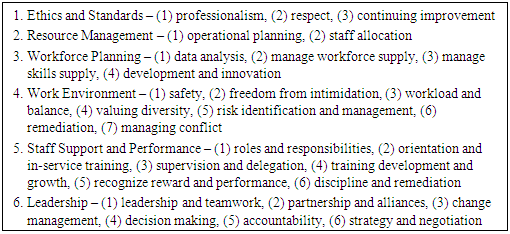

- The tool used to measure the LMTC among student manager-leaders was adapted from the competency standards developed by Una Reid and Bridget Weller for the International Centre for Human Resources (ICHR) in Nursing and International Council of Nursing (ICN) entitled as Nursing Human Resources Planning and Management Competencies [19]. An email correspondence was sent to the ICN to seek approval to use the competency framework – approval was secured later on by the researchers. The competency framework was slightly modified to fit as a survey questionnaire. The first part encompasses the demographic data of the respondents namely: age, sex, and area of assignment. Then it is followed by the six (6) parameters – ethics and standard [5, 10, 20-23], resource management [10, 20-23], workforce planning [10, 20-23], work environment [10, 20-22, 24], staff support and performance [10, 20-22, 25] and leadership [10, 20-23] – which has been mentioned implicitly in literatures regarding leadership, management and teamwork competencies (see Box 2). The LMTC questionnaire consists of 28 questions. Box 2 also shows the number of questions in each parameter. Statements that best describes the student manager-leaders were graded using a five-point Likert Scale as 5= Strongly Agree; 4= Agree; 3= Undecided; 2= Disagree; and 1= Strongly Disagree. Examples of statement include: “Staff Allocation – Creates and manages staffing patterns to meet patient care needs;” “Workload and Balance – Prioritizes workload and manages time effectively.”

|

2.4. Procedures

- Permission from key officials of the College of Nursing was secured before implementing the approved study protocol. Survey questionnaire, as well as an informed consent and invitation letter containing the purpose, procedure and significance of the study was distributed afterwards. The respondents were all in contact in the two-week Nursing Leadership and Management practicum. Members of the research team contacted the potential respondents one week prior to their scheduled clinical rotation to introduce the research and seek their participation. On the last day of the clinical rotation, the survey questionnaires were administered to the respondents, before their post-duty conference. After retrieving the questionnaires, the research team tallied the results of the survey using Microsoft Excel. Likewise, the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 17.0 was used for statistical analysis.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

- The research committee of the Our Lady of Fatima University – Antipolo College of Nursing, approved the study protocol to be ethically sound. The study was implemented following the principles stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation in this study is voluntary. Informed consent was provided, explained and clarified to the respondents. Respondents can freely withdraw from the study at any point in time. Confidentiality was assured in the course of the study.

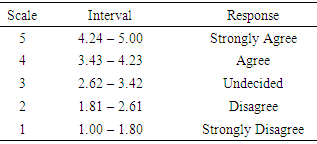

2.6. Data Analysis

- SPSS was used for the descriptive and inferential analyses of the data. Percentage distribution was used to describe the demographics of the student manager-leaders. Likewise, LMTC as evaluated by the three groups of respondents were presented using weighted mean. The scale of interpretation was computed as follows (see Table 1).

|

|

3. Result

3.1. Demographic Data of Student Manager-Leaders

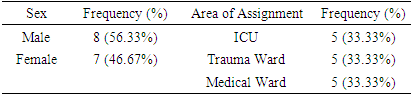

- In Table 3, majority of the student manager-leaders were male (n=8, 56%). The 15 student manager-leaders were equally distributed (n=5, 33%) in all three clinical areas in the research locale. Only the two demographic data were captured since the respondents were chosen purposively and that it is expected that majority of the demographics of the student manager-leaders are the on the same course (e.g. age, year level in nursing studies, nursing course currently enrolled).

|

3.2. Leadership, Management and Team Competencies

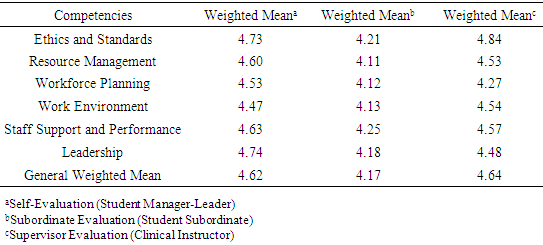

- Table 4 shows the calculated weighted mean of the LMTC of student manager-leaders as evaluated by themselves, student subordinates and clinical instructors, on the six subscales of the Nursing Human Resources Planning and Management Competencies. A general weighted mean of 4.62 and 4.64 for the self-evaluation of the student manager-leaders and clinical instructors was observed, while a general weighted mean of 4.17 was gleaned from the evaluation of the student subordinates. It can be also gleaned that Leadership (4.74), Staff Support and Performance (4.25), and Ethics and Standards (4.84) were the highest ranked subscales according to the student manager-leaders, student subordinates and clinical instructors respectively. On one hand, “Work Environment” (4.47), “Resource Management” (4.11), and “Workforce Panning” (4.27) were rated as the three lowest ranked subscale as evaluated by the three groups of respondent.

|

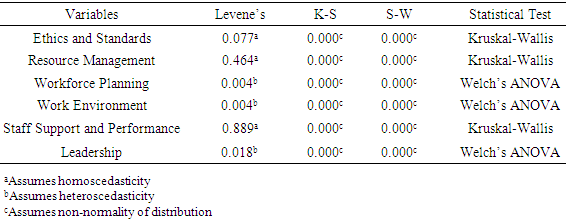

3.3. Comparison of the Evaluations made by the Three Groups of Respondents

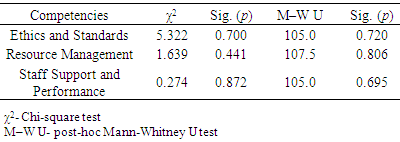

- A Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to compare the evaluation of the three groups of respondents (see Table 5). The analysis shows that all the computed p values for Ethics and Standards (p=0.700), Resource Management (p=0.441), and Staff Support and Performance (p=0.872) are above the level of significance (α = 0.05). Consistently, the post-hoc Mann-Whitney U (M-W U) test shows an alpha level of significance above 0.05, thus denoting absence of significant difference among the evaluations.

|

|

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Result

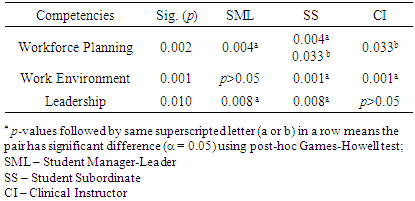

- In this study, self and supervisor evaluation of the LMTC of student manager-leaders shows strong agreement. In the same way, subordinate evaluation shows agreement. Some may claim that nursing educational programs do not really prepare nurses for leadership and management roles [30], hence nursing education must continually incorporate concept of leadership, management and teamwork at the stage of basic nursing education and training [17]. Earlier studies also show that nursing students tend to trust their competence at the point of graduation [31, 32]. Nursing student’s claim may be seen positively and can be a basis for a successful nursing education. It is essential that student nurses – whom will soon be new nurses – be confident of their competence, however caution must be regarded for overconfidence based on inaccurate evaluations can be devastating to new nurses [33].The student manager-leaders themselves rated “leadership” highest, compared to other subscales. It concurs with other studies [17] wherein student nurses, like the student manager-leaders in this study, rated themselves as highly competent leaders. Literatures agree that effective leaders may have high self-rating of leadership competencies because effective leaders have a considerable degree of self-regard [34], self-confidence [35] and self-efficacy [36]. Teaching leadership to nursing students may pose a challenge among educators considering the gaps between knowledge and practice. Educators can teach the theoretical concepts of leadership, but learning how to be a leader is an embodiment of one’s knowledge, skills and attitude that requires situational awareness and time to develop [37].For the student subordinates, “staff support and performance” ranked as the highest LMTC subscale of student manager-leaders. The main focus of staff support and performance is the ability to foster an enabling working environment that can contribute to recruitment and retention of nursing workforce [19]. Experts concluded that high leadership competencies of nurse unit managers has correlation with subordinates’ reduced turnover rate, increased job satisfaction, and patient’s improved outcome [38, 39]. In addition, effective performance of nurse manager-leaders’ are vital in empowering subordinates’ to foster efficient performance in their workplace [40]. Meanwhile for the clinical instructors, “ethics and standards” ranked as the highest among other subscales of LMTC. Ethics and standards focuses on ensuring that nursing practice is ethically and professionally sound [19]. Available literature acknowledged the role of nursing educators in promoting professional and ethical competence among students [41]. Both nursing educators and students agree in the importance of ethics in nursing education as it enhances perception to ethical issues and facilitated development of analytical and reflective skills [42]. No significant difference was seen between the three groups of rater, for Ethics and Standards, Resource Management, and Staff Support and Performance. The rating for the above mentioned LMTC variables were nearly identical for the three groups. Though there was a trend for student manager-leaders and clinical instructor to give higher rating, the differences were not great enough to be statistically significant. This is similar to the study of Hemalatha and Shakuntala in which nursing students’ competencies were rated above novice level [26]. Conversely, a significant difference was seen in LMTC variables namely Workforce Planning, Work Environment and Leadership. Harris and Shaubroeck provided possible reasons that may affect variances among sources of ratings. Firstly, it is possible that different raters may have diverse knowledge of others’ ratings. For instance, raters may receive informal feedback while in the course of the clinical rotation – such contamination may lead to variances. Degree of interaction among raters may also affect the ratings such that a group of rater who may have more interaction with co-raters than in others [43]. Other factors may include amount of rater training [44], purpose of rating [45], and motivation of the rater [46]. Also, the significant difference seen in the evaluations concurred with the study of Shang and Yu [47] on the managerial competencies based on self (manager) and subordinate-evaluation. Subordinates’ lower rating may be a result of varied perceptions of the role requirements of the managers within the group or organization [43].

4.2. Implications

- Nursing education may lean towards the development of fundamental clinical knowledge and skills to prepare students for future roles as nurses, the current curriculum for bachelor’s degree in nursing in the Philippines is in fact geared towards producing highly competent nurses equipped with theoretical, clinical and practical knowledge, skills and attitudes. The findings of the study may show overall positive result in terms of the LMTC of student manager-leaders, even so stakeholders responsible for nursing education must continue to provide a conducive learning environment to further hone student nurses’ knowledge, skills, and attitude in leadership, management and teamwork. This should start as early as in the baccalaureate level. While self-evaluation of student manager-leaders may reflect self-regard [34], self-confidence [35] and self-efficacy [36] as discussed – student subordinates’ evaluation may suggest actual capacity to manage and lead, as posited in transformational theory of leadership. This theory presents leaders’ ability to inspire followers to accomplish more than what is expected of them by creating an environment that will facilitate productivity [48]. Thus, evaluation from student subordinates may be considered indispensible in appraising students who are taking the practicum portion Nursing Leadership and Management course. Nursing educators are in a key position in doing this. Discussions on leadership, management and teamwork may not be contained inside the classrooms and in one semester or a year, and its context must not remain on its theoretical aspects. But rather, nursing educators must take opportunities to include practical and real life applications of leadership, management and teamwork concepts, to further facilitate learning. This may pose a challenge, but this may also serve as opportunity to showcase innovative teaching styles of nurse educators. Future studies concerning innovative teaching strategies for LMTC, culturally bound to Filipino nursing students, are encouraged.Regular evaluation of student nurses’ competencies are highly advocated for it promotes self-awareness. The latter is defined as one’s understanding of desires, values, motivations, goals, emotions, strengths and weaknesses. The development of self-awareness is supplemented by feedback from others – like evaluation activities [49]. Furthermore, self-awareness is related to one’s level of performance and influence. In fact, leaders with high level of self-awareness tend to be more aware and more open for improvement since they are much conscious of their own strength and limitations [50].The health facilities itself is a good arena for nursing students to observe and document leadership, managerial and inter-professional practices. Discussions on this may be considered aside from that of clinical cases. At the same time, nurse educators must remain prudent in supervising nursing students. Certainly, hospitals offer real-life scenarios where nursing students can learn, however it is also the responsibility of the nurse educators to delineate best practices from those which are not.

4.3. Limitations

- Several limitations exist in this study, thus findings must be inferred with prudence. Even so, this study was able to collate and summarize gathered data to allow description of the LMTC student manager-leaders. The research design and purposive sampling methodology and, small and unequal sample size used in this study were only drawn from a single private university affiliated in a public tertiary hospital were the respondents had their clinical rotation. In effect, this limits generalizability of the findings. Parallel research can be conducted utilizing larger sample from different universities and hospitals – public and private – through randomized sampling to increase representativeness. Choosing only senior nursing students for pilot testing can be considered as a limitation. Including faculty members and practicing nurse manager-leaders may offer additional perspective that can improve further the reliability of this study. The two-week clinical rotation of senior nursing students as student manager-leader might be too short to actually show LMTC. Future study can also be done on other clinical areas, since this study was limited only to the three available clinical areas – Trauma Ward, Medical Ward and Intensive Care Unit. Instead of cross-sectional design, future researchers can consider conducting a longitudinal prospective study to explore other underlying factors related to the focus of the study. Finally in terms of employing the evaluation, it may be valuable to consider a peer evaluation – an evaluation from a fellow student manager-leader – aside from self, subordinate and, supervisor evaluation. Considering the abovementioned methodological recommendations can increase the generalizability of the future studies.

5. Conclusions

- This study describes the leadership, management and team competencies of student manager-leaders. Implications for nursing education have been made, based on the findings of the study. Particularly, this research emphasizes the need to create conducive learning environment and innovative teaching methods to instill theoretical and practical concepts of leadership, management and team work. In addition, regular evaluation of LMTC has been also posited. Data collected and analyzed has been helpful in describing the variables, but there are obvious methodological limitations in this study, hence it yields low generalization of results. Methodological suggestions have been made to provide reference for future researchers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The researchers would like to express their sincerest gratitude to the following individuals:Hans Christian Vitug, RN, MAN Ace Lenon Babasa, RN, RM, MSAHPMelvin Medes, RN, RM, CRN, MANCheryl Sebison-Lenon, RN, MANFrancis Castro, MBA

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML