-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2016; 6(3): 77-86

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20160603.03

Narrative Approach in the Investigation of Learning Mediated by ePortfolio

Kirsten Nielsen1, Birthe D. Pedersen2, Niels H. Helms3

1School of Nursing, VIA University College, Holstebro, DK, Denmark

2Department of Clinical Research, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, DK, Denmark

3Department for Research and Innovation, University College Sjælland, Vordingborg, DK, Denmark

Correspondence to: Kirsten Nielsen, School of Nursing, VIA University College, Holstebro, DK, Denmark.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The aim of this article is to present and discuss a narrative approach to the investigation of learning mediated by ePortfolio. It is a qualitative study within nursing education. The method was inspired by the French philosopher, Paul Ricoeur, with focus on Ricoeur’s theory of narrative and interpretation. Data were generated through participant observations, narratives and portfolio documents. The discussion revolves around the extent to which the method was effective in the generation of data, how the data were interpreted, and how the study contributed to the discourse on learning in clinical settings. The principal conclusion is that the method was practicable for the generation and interpretation of data. Thus, the study contributed to a more detailed understanding of learning in nursing education, especially as regards the discourse on learning in clinical settings.

Keywords: ePortfolio, Learning, Nursing education, Qualitative research

Cite this paper: Kirsten Nielsen, Birthe D. Pedersen, Niels H. Helms, Narrative Approach in the Investigation of Learning Mediated by ePortfolio, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 6 No. 3, 2016, pp. 77-86. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20160603.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The article presents and discusses a qualitative method inspired by the French philosopher, Paul Ricoeur (Ricoeur, 1976; 1991). The method was chosen to study how an electronic portfolio (ePortfolio), in this case a tool designed to facilitate four learning styles, mediates the learning process of nursing students in clinical settings. The portfolio design was inspired by Honey and Mumford’s theory of learning styles (Honey & Mumford, 2000) and the Swedish psychologist and portfolio pioneer, Roger Ellmin (Ellmin, 2001). The ePortfolio consists of a mandatory element, for planning and documentation of students’ study activities and an elective element in which the students records what they learn in their clinical placements. In this study, learning is understood as a lifelong dialectical process according to the Danish professor and psychologist, Mads Hermansen. This understanding of learning builds on a row of theories by Skinner, Thorndike, Pavlov, Bateson, Colaizzi, Rogers, Bruner, Gergen and Ricoeur (Hermansen, 2003). According to Hermansen, learning is represented by a new knowledge, skill, emotional reaction, or as a behavioural or attitudinal change in the learner. Learning can be initiated by both internal and external motivation, and takes place both in the learner and in the learner’s relation to the world around them. The process of learning is both unconscious and conscious, and includes factors such as habitus and reflection, learning by feed-forward and feedback, toil and exuberance (Hermansen, 2003). Thus, students learn by interaction and communication, by involving themselves both physically and emotionally in the surroundings and in other people’s lives and by reflecting on practice. Nursing by Merry E. Scheel is seen as an interactional practice, encompassing theoretical, ethical and practical knowledge and ability. The students have to learn to make professional judgements based on theoretical knowledge and ability, insights into unique patient situations and ethical considerations about relationships with various stakeholders. They also have to learn which actions should be taken, based on their judgements. The aim of nursing is the care of patients that includes health promotion, prevention of illness, rehabilitation, and to relieve suffering (Scheel, Pedersen, & Rosenkrands, 2008). When students write in ePortfolio about their experiences in clinical settings, their words are like footprints that give evidence about events and how the students experienced them. Their writings provide narratives about considerations and interventions in nursing practice. These are the grounds on which we consider that Ricoeur’s theory of narrative and interpretation is applicable to this study.

2. Background

- In a review of the Danish nursing curriculum, whose aim was to better prepare students for clinical practice, it was recommended that the revised educational programme take into account differentiation in the student body (Ministry of Education, 2008). This presented an opportunity to develop and implement an ePortfolio, intended to support differentiated guidance and formative evaluation of students. Even though the ePortfolio was designed to facilitate four different learning styles, some students responded that they experienced that they got no help from using the ePortfolio in the learning process. Therefore, we wanted to investigate how it could be that the ePortfolio helped many, but not all students.The literature also indicates that both benefits and barriers can be found in the implementation of ePortfolio in nursing education (Jones, Sackett, Erdley, & Blyth, 2007; Allern, Engelsen, Dysthe, Slåtto, & Øvregård, 2008; Taylor, Steward, & Bidewell, 2009; Bogossian & Kellett, 2010; Shepherd & Bolliger, 2011; Garret, MacPhee, & Jackson, 2013; Green, Wyllie, & Jackson, 2014; Andrews & Cole, 2015), and that both nursing students and preceptors can benefit from insight into preferred learning styles in their attempts to maximize students’ learning potential (Austin, Closs, & Huges, 2006; Rasool & Rawaf, 2007; Fleming, Mckee, & Huntley-Moore, 2011; Boström & Hallin, 2013; Hallin, 2014; Li, Yu, Liu, Shieh, & Yang, 2016). Conversely, some authors express concern about the risk that teachers can label students as certain types of learners (Cassidy, 2004; Coffield, Mosely, Hall, & Ecclestone, 2004; Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, & Bjork, 2009). Because our literature search returned no articles relating to ePortfolio designed to facilitate learning styles in nursing education, the purpose of our study was to investigate how such an ePortfolio mediates learning in clinical settings. The article presents and discusses Ricoeur’s approach to the narrative language using metaphors, text, discourse, and interpretation. The concepts are related to the specific research process used in the study of learning mediated by ePortfolio. The discussion revolves around three issues: firstly, whether the method is practicable for generating data about learning in a clinical setting; secondly, how the body of data should be interpreted to ensure that interpretations are trustworthy, and, finally, the extent to which the study can contribute to the discourse on learning in clinical settings.

3. Key Points from Ricoeur’s Theory

- Ricoeur (1913-2005) considered the main purpose of philosophy to be the ontology of human beings, society and the world. He endeavoured to settle the conflict of interests between, on the one hand, science, objectivity and technical expertise and on the other hand, humanistic culture, personal choice and ethics – or, in other words, to settle the conflict between explanation and understanding. Ricoeur argued for an understanding of sciences as a unity, including their metaphysical, ethical and aesthetical aspects (Ricoeur, 1993; Kemp, 1999) and developed his thinking in relation to a number of renowned philosophers (Tan, Wilson, & Olver, 2009). He named this aim concrete reflection, as it is the concrete human being in the living history that we endeavour to understand (Ricoeur, 1993, p. 15). Ricoeur’s work is considerable in its scope; in this article, only the key points most relevant to our method are drawn upon.Narrative and metaphorRicoeur was a proponent of the application of narratives in science, because telling narratives is part of being human, and narrative language expresses both the interaction between a person and the environment and the person’s interpretation of the interaction. Narratives are sources of realisation, experience and identity. Ricoeur was inspired by Aristotle in his understanding of narrative in terms of a threefold mimesis, but put more emphasis on the connection between time and narrative (Ricoeur 1984, pp. 52-54). Mimesis is the production of meaningful contexts concerning human actions and their value, as told in narrative language. It is structured with a beginning, a plot and an end, but it is more than a structure. It is also a process of creating new meaning: Mimesis1 concerns the narrator’s current impression of an event, coloured by his preconceptions. Mimesis2 is about how the narrator decides to construct the narrative in order to make explicit his impression of the event. Mimesis3 concerns the listener or reader trying to understand the content of the oral or written narrative. This understanding is influenced by the individual’s preconceptions. Thus, the content of a narrative refers to the past, the present and the future. Personal narratives frame relations, events and values into a coherent whole, and interpretation and reinterpretation guide living and acting in specific situations (Ricoeur, 1984, pp. 54-76). The narrative language contains symbolic expressions and metaphors. Ricoeur made an effort to show that a metaphor has a surplus of meaning, from a semantic point of view (Ricoeur, 1979, pp. 162-164). The metaphor relates more to the semantics of sentences than to the semantics of words, as a metaphor only becomes a meaningful expression as a remark or sentence (Ricoeur, 1979, p. 168). Because a metaphor is often a surprising fusion of words that are not usually connected, it is a semantic renewal of the language that tells something new about the reality (Ricoeur, 1979, pp. 171-172). It is the relation between the literal and the figurative meaning of a metaphoric expression that provides the surplus of meaning. Knowing the literal meaning allows for the understanding of the new, extended meaning (Ricoeur, 1979, pp. 173-189). To understand the full meaning of the metaphor, we must push aside our preconceptions. Thus, Ricoeur draws a parallel between a narrative language with metaphors and the language of science. Both languages have the intention of opening up a different world than that immediately given. In this manner, a new and different understanding becomes possible (Ricoeur, 1979, p. 190). Text, discourse and interpretationRicoeur defines a text as any transcribed discourse, and a discourse is: when someone says something to somebody about something. When what someone says to somebody is transcribed, it becomes a text. So, a text is a discourse preserved for future readers (Ricoeur, 1993, pp. 32-33). Thus, a discourse can be both spoken and written, and writing is the full manifestation of the discourse. When a discourse is written, the dialogue and face-to-face relation between the speaker and the listener are replaced by a relation between an author writing and a reader reading, who are independent of one another. A distance between the author and the text appears. The reader has no opportunity to ask the author questions in order to understand the content (Ricoeur, 1979, pp. 138-142; 1993, pp. 32-38). Ricoeur was a proponent of a two-dimensional approach to language that concerns both semiotics and semantics, because language depends on both characters and sentences (Ricoeur, 1979, p. 116). An isolated word is neither true nor false, because it takes a minimum of a connected noun and verb to express a statement in language and thoughts that stretches further than the words. Therefore, the sentence is the mainstay of the language and the minor unit in a discourse (Ricoeur, 1979, pp. 109-110). A discourse is also an event where somebody is using the language to tell somebody about something (Ricoeur, 1979, p. 139). Because what they tell is a message about something in the world, the message refers both to the world and the speaker. The message is composed of one or more sentences with statements that make the message meaningful. Thus, the discourse as an event and as a message is a dialectical unit of event and meaning in the sentence (Ricoeur, 1979, p. 121). In the process of transcription, the discourse as an event disappears, because it is only the deliberate attempts to make the relation between event and meaning external that get written (Ricoeur, 1979, pp. 138-139). The semantic autonomy of the text appears through writing, because the text is detached from the author’s understanding of the world. Meaning becomes a dimension of the text, because the author is not present. The meaning of the text is open to any reader and their interpretations. This is where hermeneutics begins (Ricoeur, 1979, p. 143-145). The purpose of interpretation is to implement something unfamiliar into one’s self-perception. According to Ricoeur’s interpretation, the dialectics is between explanation and understanding, because explanation and understanding tend to overlap: We explain something to facilitate someone’s understanding of it, and the person concerned can explain what s/he understood. Conversely, to explain is to make something explicit, to describe messages and meanings. To understand is to realise messages and meanings into a whole. There is a difference between explanation and understanding, but to explain something you need some understanding of the subject (Ricoeur, 1979, p. 194). The first level of understanding comes from a naïve reading of the text as a whole. Naïve reading means reading and sensing the text openly with preconceptions set aside. The text allows for several constructions, and there is no evidence to evaluate what might constitute the most important elements. It is a naïve guess about the meaning, so we need to examine the text to qualify our guess in the subsequent steps of interpretation (Ricoeur, 1979, p. 197-199). The specific structure of the text cannot be deduced from the structure of the single sentences, because the ambiguity of the sentences is different from the ambiguity of the whole text. Beginning the interpretation by understanding the whole is one way to delimit the number of possible constructions. However, reconstruction of the text is a circular process, because impressions of a certain whole enter into recognition of the parts and vice versa (Ricoeur, 1979, pp. 199-200). The second level of interpretation is the structural analysis, which plays an explanatory role and provides an objective distance to the text. It is about establishing different bodies of connected units of meaning and units of significance from parts of the entire data material. Afterwards, the units are integrated into larger themes, which together make up the explanatory structure of the text (Ricoeur, 1979, p. 210-211). Ricoeur suggests that structural analysis is a step between the naïve interpretation of the whole and the critical in-depth interpretation. It is in the structural analysis that it is possible to facilitate the dialectics between explanation and understanding and continue the hermeneutic cycle until a trustworthy interpretation is found; trustworthy, because Ricoeur draws attention to the fact that not every interpretation holds (Ricoeur, 1979, s. 212-215). The third level of interpretation concerns critical interpretation and discussion of the themes in order to underpin the themes and complete the new text. To demonstrate that one interpretation is more trustworthy than another is different from showing the truth of a conclusion; so, in this sense, validity is not equal to verification. Instead, the third level of interpretation is a discipline of argumentation in the sense of the interpretation of laws with circumstantial evidence pointing in the same direction that provides the basis of science concerning the individual (Ricoeur, 1979, pp. 202-213).

4. Methods

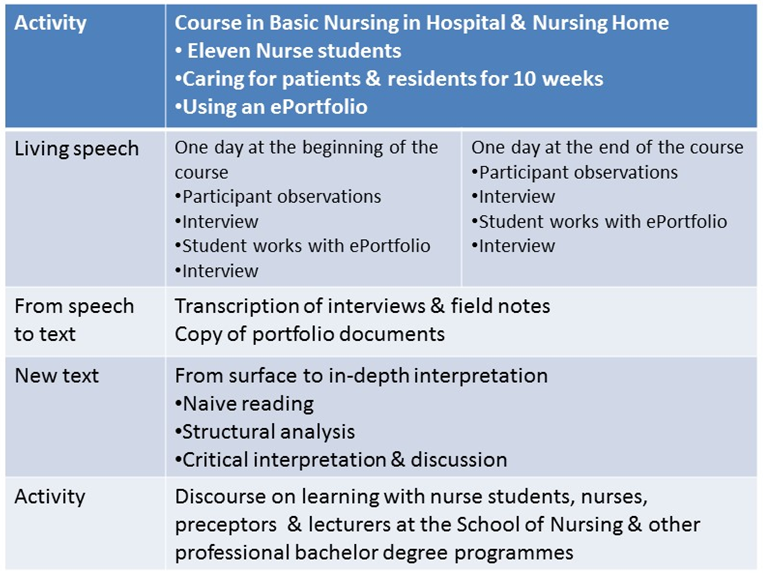

- The design takes a phenomenological-hermeneutic approach inspired by Ricoeur (Ricoeur, 1976; 1984; 1991) and later developed in nursing research (Pedersen, 1999; Wiklund, Lindholm, & Lindström, 2002). Ethical Guidelines for Nursing Research in Scandinavia (NNF, 2003), including the Helsinki Declaration, were followed. The informants received oral and written information and were included after giving informed consent. The study was submitted to the Scientific Ethics Committee and the Danish Data Protection Agency.Figure 1 gives an outline of the research process, which is further explained below.

| Figure 1. Illustration of the research process |

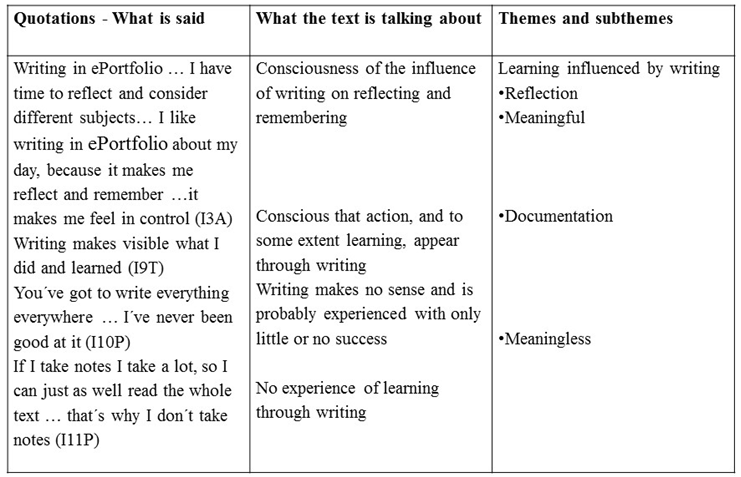

| Figure 2. An illustration of the structural analysis |

- The critical interpretation and discussion are based on the themes that emerged through the naïve reading and structural analysis. The themes were related to theory and other current research results. The interpretation involved a movement from a specific comprehension to a common comprehension, and the interpretation and discussion related to the research questions continued until argumentation for a trustworthy interpretation was found. According to Ricoeur the final activity in the research process was communication of the research results, which formed the content of three articles (Nielsen, Pedersen, & Helms, 2015a; 2015b; 2015c).

5. Discussion

- The following three paragraphs discuss the method used to generate data, the interpretation of data and the contribution to the discourse on learning, respectively. Discussion on the method used to generate dataA phenomenological-hermeneutic approach was chosen because learning was considered to be a phenomenon, and according to Ricoeur’s theory, phenomenology and hermeneutics work in a dialectical relationship. A phenomenological description gives an impression of the surface, but because it is not always obvious why human beings act as they do, it is necessary both to describe and interpret in order to gain an understanding about how humans learn (Ricoeur, 1976; 1991). In this case, the human beings to be understood were nursing students. The question was how to generate data about how students learn in clinical settings, including how they use the ePortfolio, and to what extent the mandatory and elective parts of ePortfolio support reflection on and the learning of nursing. Because nursing is an interactional practice encompassing theoretical, ethical and practical knowledge and ability (Scheel et al., 2008), the students have to learn by interaction and communication with the patients and other collaborators. Students must involve themselves physically and emotionally in practice in order to learn the arts and crafts of nursing and recognise the various nuances of reactions from patients, relatives and other health professionals. In order to generate data about this, we had to observe the students in the clinical settings. It would not be sufficient only to interview the students, because part of the learning would be unconscious (Hermansen, 2003), which is why students would not be able to tell about it.Students must also reflect on practice in order to achieve competence to make professional judgements concerning how to promote health, prevent illness, rehabilitate and relieve the suffering of the patient. It is a complicated process, because it deals with general theoretical knowledge, insight into the situation of the current patient as well as ethical considerations about how to support and respect the patient under the current circumstances. Because at least part of this reflection takes place inside the student, we had to generate data in a way whereby the reflections would be external. It was done by asking the students to write in the ePortfolio with or without pedagogical tools integrated in the elective part of the ePortfolio and by interviews. Data about the part of reflection already verbalised were generated by participant observations as well as by interviews. Data about what initiated and promoted learning were, thus, generated in the clinical setting in three ways, which are elaborated below. This is in accordance with Ricoeur’s theory, because it was the learning process of the human being in the present situation that we aim to understand (Ricoeur, 1993, p. 15). So, how was it realised?Participant observations are rooted in an ethnographical approach to research. Staying in the field being studied reveals what people do, what they say and know and what artefacts they use. Thus, participant observations bring to light the cultural meanings people use every day. In the ethnographical approach, researchers are considered to be a part of the social world they are studying, and therefore not objective but reflective and interpretive in their work. Nevertheless, when generating data, it is necessary both to be aware of and minimise preconceptions and thereby be open to the perception of the interviewee and the situation. To generate data, researchers observe, listen, ask questions and collect artefacts from the field. It is important to be able to alternate between working closely with the actors and to distance oneself in order to reflect and perhaps make adjustments to one’s interpretation (Spradley, 1980). The field in this study was clinical settings in hospitals and a nursing home, where the nurse trainees were learning basic nursing. Conducting research within one’s own work culture demands even more attention to strike a balance between being close to the field and distanciation, because something could be taken for granted. On the other hand, it was necessary to know the field in order to understand what was happening (Spradley, 1980). Thus, both Ricoeur and Spradley emphasise the importance of distanciation in the research process. The participant observations generated data on how the ePortfolio was employed, and an external perspective on learning gained from interactions between students and the clinical setting. However, as learning was seen as both an external and internal process (Hermansen, 2003), data from interviews and portfolio documents were necessary to provide an external expression of the part of the learning process inside the learner. The students’ written experiences, reflections or self-evaluation expressed their thoughts, reactions, learning level and learning needs. It was a written discourse and a text open to interpretation. It supported and supplemented the interviews. Aspects of the learning process that were unconscious to the student – for instance, a cultural habit of how they met the patients, as illustrated in the example of the naïve reading – appeared from both observations in the clinical settings as well as from interviews and portfolio documents at the onset of the interpretation.Ricoeur was preoccupied with linguistics and discourse, because that is where culture arises. Thus, both Ricoeur and Spradley emphasise the importance of the language as the primary means for transmitting culture from generation to generation (Ricoeur, 1976; Spradley, 1980, p. 12). Firstly, learning took place in an interaction between the student and the clinical setting as well as inside the student. Secondly, as narrative language expressed both the learning in interaction between the student and the environment and the student’s interpretation of the learning, it was a source of realisation and experience and provided an impression of the identity of the student. Therefore, asking students to tell us about what they had experienced and listening to the narrative language could provide an explicit expression of the student’s learning and interpretation of the interaction in the clinical setting.Each interview began with an open question in order to let the student begin the narrative at the point that seemed natural to the student concerned. The researcher avoided interrupting the interviewee’s associations, thus allowing for a free expression of what was important to the student. It could be argued that, in asking these questions shortly after practising care and working with ePortfolio, respectively, what students told could not always be considered as narratives with a beginning, a plot and an end. Nevertheless, the narrative language expressed the students’ experiences of interaction with patients and their environment, their preconceptions, values, feelings and reactions, regardless of whether it was spoken or written in the ePortfolio. Sometimes, metaphors appeared in the narrative language. They told us something surprisingly new about learning. For example, one student felt caught in the act when writing in her portfolio. This seemed to be a metaphor for a looming sensitivity that arose from the fact that her preceptor would read her personal concerns about nursing practice. It was the literal meaning of “being caught” that allowed for the understanding of how she felt and her preconceptions of being a nursing student. When we set aside our preconceptions, we gained new knowledge about what could inhibit writing in ePortfolio. Of course, the students mostly expressed in words the things they were aware of, and for this reason it was crucial that both an internal and an external perspective on the learning process were possible, in order to generate reliable data. Critics could argue that narratives are not valid data, because they are subjective and told by individuals who are colouring the narratives with their values. Nevertheless, in this study, our aim was actually to investigate what it meant to the subjects to learn in a way that was mediated by ePortfolio. According to Ricoeur, validity in this sense is not verification but rather argumentation with evidence supporting the same conclusion (Ricoeur, 1979, p. 202). Thus, the research process guided us to a trustworthy interpretation of students’ individual learning. Furthermore, it could be argued that eleven informants comprise too small a cohort from which to make generalisations. However, generalisation was not the aim of the study. As emphasised above, the aim was to find out how the ePortfolio mediates the individual learning process of the students with different learning styles and to identify themes common to these students. For this reason, we considered that the design and method employed were appropriate to the aim of the study. This was supported by former qualitative research projects, where the method was found to be appropriate for research into present situations of individual human beings (Pedersen, 1999; Wiklund, Lindholm, & Lindström, 2002; Lindseth & Nordberg, 2004; Dreyer & Pedersen, 2009).Discussion on interpretationThe comprehensive collection of texts to be interpreted came from field notes, interviews and portfolio documents. When portfolio documents were copied and the narratives and field notes were transcribed, they were separated from both students and other actors and objectified. The text took the place of the spoken words. It was the text – not the students or other actors – who spoke. This was the first step in objective distanciation. Thereby, the text became open to interpretation. Interpretation covers both explanations at a critical distance and facilitation of understanding. As in life itself, interpretation was essential in the research process through which the researcher created meaning, coherence and understanding of the data about learning as mediated by ePortfolio. The interpretation began with the phenomenological part of the interpretation, which was the naïve reading with preconceptions consciously minimised and the senses open to what moved us, when reading and re-reading. Otherwise, we risked perceiving only what we expected to find. However, because mimesis3 is about the reader’s effort to understand the content of the text, and this process is also facilitated by the reader’s preconceptions (Ricoeur, 1984, p. 77), what also happened was that we related our preconceptions to the discourse of the text, and a new holistic understanding of the meaning content thereby emerged. As researchers, we had to strike a balance between reading the texts open-mindedly and using our preconceptions to guess what was important in order to get a surface impression of what was learned by students participating in nursing care and what was mediated by the ePortfolio. This was the reason why this part of the interpretation had to be followed by structural analysis, critical interpretation and discussion related to theory and other research results. The structural analysis is the explanatory part of the interpretation. This level provided a productive distance to the texts. Texts about caring for the patients and texts about using ePortfolio were seen as objects in the light of understanding the whole, which derived from the naive reading. According to Ricoeur, this is important, because “the specific structure of the text cannot be deduced from the structure of the single sentences, because understanding the whole is an aspect of delimiting the number of possible constructions of the sentences” (Ricoeur, 1979, pp. 199-200).This was the reason for having structural analysis as the second level of interpretation, contrary to Tan, Wilson and Olver, who began with the structural analysis and followed with naïve reading (Tan et al., 2009). In the structural analysis, the texts were read again. Expressions of one or more connected sentences were systematised by asking what the text said about something. The next step was to ask what the expressions were talking about, in order to establish different bodies of connected subjects from parts of the whole. Going backwards and forwards through the texts looking for units of meaning and units of significance allowed for themes to emerge, as illustrated in Figure 2. The subjects were gathered into larger themes that were relevant to the research questions, and the structural analysis was completed by writing a new text with an overview over units of meaning, units of significance and the clarified themes.The research questions concerned trainee nurses’ learning as mediated by ePortfolio. According to Hermansen, learning can appear as new knowledge, skill, an emotional reaction, or behavioural or attitudinal change in the learner (Hermansen, 2003). We did not expect it to simply appear from the text. It was necessary, in line with Ricoeur, both to describe and interpret in order to achieve knowledge about students’ learning. However, as referred in the example of the naive reading we did find some traces of learning in the texts; for instance, in the case of the student who changed her approach to the patients. According to Ricoeur, traces in a text are present expressions of the past, because mimesis1 is the narrator’s current impression of an event coloured by preconceptions, and mimesis2 is how the narrator decided to construct the narrative in order to express the impression of the event (Ricoeur, 1984, pp. 54-70). So, in this case, traces were present expressions of the student’s interpretation of past interactions between the student and the patients in the clinical setting, which, through interpretation, appeared to be steps in the learning process. Critical interpretation and discussion was the final and in-depth part of the interpretation. To qualify the themes and uncover immanent insight in the content, relevant theories and research results were involved, because, in accordance with Ricoeur, when the discourse of the text from the structural analysis was related to the discourse of other texts, the interpretation could swing backwards and forwards in order to look at all sides of the research questions: how the ePortfolio was employed in clinical settings, whether the ePortfolio mediated reflection and learning of nursing in clinical training, and what characterised the interaction between learning, learning styles, and ePortfolio use. The process continued until we could expound a trustworthy interpretation of the results, underpinned by relevant research results as well as by internationally approved theory that supported the same conclusion; i.e., when the results reached into the future and beyond the context and the informants in this study to something common to all learners.Contributions to the discourse on learningSeveral surveys on ePortfolio and students’ learning styles have been undertaken. Much important knowledge about barriers involved in portfolio use, such as lack of clear guidelines for portfolio work (Taylor, Steward, & Bidewell, 2009), students’ difficulties in gaining access to computers and ePortfolio, lack of time for portfolio use, and staff being reluctant or having difficulties guiding ePortfolio use (Bogossian & Kellett, 2010) is provided by way of these surveys. However, there is an inherent risk that surveys with students as informants do not throw light on some issues of importance, because students are often conscious of inhibitors in the surroundings and unconscious of inhibitors inside themselves. This study generated knowledge from narratives, participant observations and portfolio documents. Because the narratives were initiated with one open question, the interviewee could tell their story in the way that seemed meaningful, instead of answering questions that originated out of our preconceptions. In interpreting narratives and portfolio documents, where the students wrote on their own initiative, this method contributed some new kinds of inhibitors from inside the students such as students´ vulnerability and students thinking that they learn only by acting or by dialogue with their preceptors. These findings are unfolded in the article about portfolio use in clinical settings (Nielsen, Pedersen, & Helms, 2015b).Findings about increased consciousness of one’s own learning process and nursing in clinical settings through students planning their own individual way to meet the learning outcome of the course are unfolded in the article about the mandatory part of the ePortfolio (Nielsen, Pedersen, & Helms, 2015a). Surveys on learning styles contributed with important knowledge about the ability to change preferred learning style (Fleming, Mckee, & Huntley-Moore, 2011), and that it is important to both students, teachers, and preceptors to use time to become conscious of one’s own preferred learning style (Boström & Hallin, 2013; Hallin, 2014; Li, Yu, Liu, Shieh, & Yang, 2016). The contribution of this study is that a combination of ePortfolio and learning styles was important for both students and preceptors, so that learning to be a nurse could be based on the student’s preferred learning style and subsequently form the basis for the development of other learning styles. Findings about the interactions between learning, learning styles and ePortfolio are dealt with in the article about the elective part of ePortfolio (Nielsen, Pedersen, & Helms, 2015c).

6. Conclusions

- A phenomenological-hermeneutic approach is practicable for studying how an ePortfolio designed to facilitate four learning styles mediates students’ learning in clinical settings. The employed approach, that generated data, including participant observations, interviews and portfolio documents, contributed to a more detailed understanding of learning in nursing education. This understanding was facilitated by the narrative language, because language mediates understanding of learning from the learner’s as well as from the researcher’s perspective. Interpretation through naive reading, structural analysis, critical interpretation and discussion, where the interpretation moved from a surface to an in-depth interpretation, led to a trustworthy interpretation. As the investigation involved learning in the setting of three hospitals and a nursing home, the study contributed in particular to the discourse on learning in clinical settings. Limitations of this study are that it included only first-year students in clinical settings, and that it was carried out only in one School of Nursing. Further studies could be carried out that would include students through the whole nursing programme and include a number of institutions.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML