-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2016; 6(2): 48-57

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20160602.03

The Preoperative Nutritional and Psychosocial Health Status among Patients Undergoing Open Heart Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study

Naglaa FA Youssef Elshamy1, Salwa H. Abdelaziz1, Ayman S. Gado2, Ahmed F. Hammed1

1Medical Surgical Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt

2Cardiothoracic Surgery Department, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt

Correspondence to: Naglaa FA Youssef Elshamy, Medical Surgical Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Assessing the nutritional and psychosocial health status among patients undergoing open heart surgery (OHS), particularly in Egypt, has received relatively little attention from researchers. Aim: This study aimed to describe and evaluate the preoperative nutritional and psychosocial health status of patients undergoing OHS. Method: In a correlational cross-sectional study, a sample of 84 patients was recruited in the period between January 2015 and January 2016 from a teaching hospital in Cairo. Patients were interviewed to complete four instruments: (1) Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST), (2) New York Heart Association (NYHA), (3) Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) and (4) Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21), alongside a questionnaire of socio-demographic and medical data. Results: The majority of patients were male (84.50%), married (90.50%), and employed (64.30%), with a mean age of 48.95±11.81. 43% of them had a NYHA classification III–IV. The mean Body Mass Index (BMI) was 27.90 kg/m2. 69% of patients were either obese or overweight; and 14% of them were at risk of malnutrition. The prevalence of depression (56%), anxiety (61.9%), and stress (59.5%) was relatively high. Using multiple regression analyses, the results showed that NYHA and education were not significantly associated with depression; while NYHA and age (p ≤ .01) were significantly associated with anxiety. Conclusion: The physical and psychosocial health of patients on the OHS waiting list should be continually assessed. Nurses and healthcare professionals should deliver a tailored care plan based on the patient’s age and physical functions, which can reduce preoperative depression, anxiety and stress.

Keywords: Open heart surgery, Preoperative, Body mass index, Mental health, Social support, Egypt

Cite this paper: Naglaa FA Youssef Elshamy, Salwa H. Abdelaziz, Ayman S. Gado, Ahmed F. Hammed, The Preoperative Nutritional and Psychosocial Health Status among Patients Undergoing Open Heart Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 6 No. 2, 2016, pp. 48-57. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20160602.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Heart disease is the leading cause of death in Egypt, with ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke accounting for 21% and 14% of all deaths respectively. Overall, cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality accounts for 46% of all mortality [1]. The high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. smoking, hypertension, diabetes, poor life style…etc.) contributes to a burden of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality generally in the Middle East and particularly in Egypt [2]. Overweight and obesity have also been reported as important risk factors, alongside physical inactivity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus for CVD. Open heart surgery (OHS) is one of the most commonly used procedures to remove the blockage of blood to the heart muscle, thus helping to improve the supply of blood and oxygen to the heart, relieving chest pain, enabling physical activity and improving the overall quality of life. However, the survival rate is variable after this procedure, as it is associated with many postoperative complications. Generally, the most common reasons for undertaking OHS are Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) and valve replacement (VR) [3].Several preoperative factors have been found related to postoperative health outcomes among patients undergoing OHS; such as physical condition, nutritional status, psychological status, social status and length of waiting time before surgery [4-7].The nutritional status of hospitalized patients generally reflects on their health outcomes. However, published research findings are contradictory as to whether there is an association between body mass index (BMI) and postoperative health outcomes. The research evidence is inconclusive regarding the outcomes of obese patients after OHS; although some findings do suggest that these patients end up with a higher incidence of morbidity and mortality [6]. Similarly, malnutrition has also been associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality after cardiothoracic interventions. In a multivariate analysis, low BMI, but not S-albumin, increased the risk of death while low S-albumin, but not BMI, increased the risk of postoperative infection [4]. This leads to high hospital costs because these patients have a greater need for a longer stay in hospital and specialized services [8]. Malnourished hospitalized patients are more susceptible to hospital-acquired diseases, progressed clinical complications, longer stays in hospital and in the intensive care unit, poor perceived quality of life, premature mortality, in-hospital mortality, renal complications, prolonged ventilation (>10 h), gastrointestinal complications and postoperative bleeding and reoperation for bleeding [9-15]. Screening the nutritional status and its risk factors has been acknowledged by researchers to be an integral part of caring for hospitalized cardiac patients [16].Perioperative anxiety and stress are considered to be a normal part of a person’s surgical experience; however, they can cause adverse health outcomes, particularly after surgery [5]. Preoperative patients with high levels of anxiety are more likely to experience high postoperative pain, an increased risk of wound infection and a delayed healing process [5]. Preoperative anxiety, depression and the physical health status have been found to be predictors of postoperative depression and anxiety among patients waiting for OHS [17]. It is recommended that healthcare professionals identify their patients’ preoperative feelings before heart surgery. This is essential because, in the hospital environment, nurses play a broad role in the care of people undergoing complex surgical procedures such as cardiac surgery. Nursing care ranges from delivering preoperative care and careful monitoring for early detection of postoperative complications to offering emotional and psychological support to patients and their families throughout the post-surgical recovery period. Reducing patients’ anxiety and preparing them for surgery are some of the main preoperative nursing interventions. Social support refers to the availability of trusted, reliable people who can make an individual feel cared for and valued [18]. Social support has been found to be an important factor in tolerating stressful life events, not only for reducing the incidence of disease, but also for improving health outcomes during illness. One of the important roles of nurses is to detect physical and psychosocial health problems, such as poor nutritional status, depression, anxiety and stress and how they perceive the surrounding support, which might occur during the waiting period for surgery. Thus, this study aimed to describe and evaluate the preoperative nutritional status and psychosocial health status of patients undergoing OHS. Specifically the study aimed to: 1. Evaluate selected determinants of the nutritional status of patients undergoing OHS.2. Assess the prevalence of psychosocial problems (i.e. perceived social support and mental health in terms of depression, anxiety and stress) of patients undergoing OHS.3. Identify the factors associated with the preoperative mental health status (depression, anxiety and stress) of patients undergoing OHS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

- A descriptive, correlational cross-sectional design was used in this study to: (1) determine the characteristics of people undergoing OHS and (2) explore the relationships between the identified patient variables and other independent factors [19, 20]. The study was conducted in a cardiothoracic ward in ElKasr ElAini Teaching Hospital. This hospital is one of the largest public hospitals in the Cairo region, where large numbers of patients from different socio-demographic backgrounds and from different regions in Egypt attend to have cardiac surgery.

2.2. Participants

- The target population was all adult patients undergoing OHS during the year from January 2015 to January 2016 (N = 213). A sample of 84 out of the 213 screened patients (40%), who met the specified inclusion criteria, was recruited. Inclusion and exclusion criteria Patients aged ≥18 years, who had elective CABG and/or valve replacement (VR) surgery were eligible to participate. Patients undergoing emergency surgery, or had psychological, neurological or communication limitations, were not eligible to participate.

2.3. Measurements

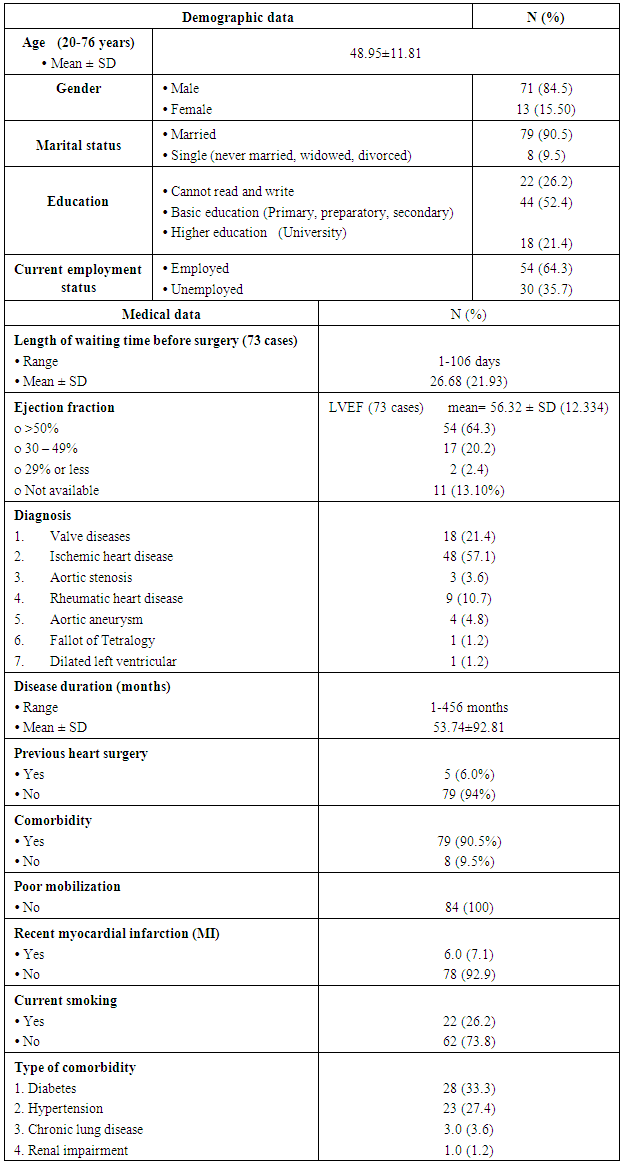

- Socio-demographic and medical data sheets: This sheet was divided into two parts: (i) the socio-demographic sheet was used to collect data such as age, gender, employment status, occupation, educational level, marital status and medical history, and (ii) the medical data sheet was used to record the diagnosis, disease duration, current smoking, comorbidity (i.e. diabetes, hypertension), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), serum albumin and other variables (see table 1).

|

2.4. Ethical Considerations and Patients’ Consent

- Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the heads of the hospital and ward. Each potential patient who met the inclusion criteria was fully informed of the purpose and nature of the study, then an informed consent was obtained from each patient who accepted to participate. The researcher emphasized that participation in the study was entirely voluntary and withdrawal from the study would not affect the care given. Patients’ anonymity and confidentiality was assured throughout conducting and disseminating this study.

2.5. Data Analysis

- The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 20 (IBM SPSS, Armonk, New York, United States) was used for the data analysis. Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize data. The Pearson product moment correlation coefficient (r) was used to assess the relationship between two parametric variables, and the Spearman's rank order correlation (rho) was used for non-parametric variables. A non-parametric statistical technique, chi-square for independence, was used to compare the frequencies of nominal variables. All statistical analyses were two tailed with p < 0.05 as the significance level.A multiple linear regression analysis using ''enter method'' was used to investigate the factors associated with mental health status (depression, anxiety and stress). Since this was an explanatory study, there was no prior decision regarding the order of entering the variables in the model [32]. The independent variables were: (1) Socio-demographic variables (age, gender, marital status, current employment status, educational level and current smoking), (2) Medical data (disease duration since diagnosis, previous surgery and LVEF), (3) Physical health status (NYHA), (4) Nutritional status parameters (albumen, HB and BMI) and (5) Perceived social support (MSPSS). The multiple regression assumptions were investigated and there was no violation of normality, linearity, multicollinearity and homoscedasticity.

2.6. Sample Size

- This rule of thumb method [N = 50 + 8 k (k is the number of independent variables)] was used to calculate the required sample size for the multiple linear regression analysis. [32]. Assuming a medium effect size relationship between the independent variables (variables significantly associated with depression and anxiety in the correlation matrix), and with alpha=0.05 and β=0.20 [32, 33] the required sample size for developing the regression model for depression and anxiety were 74 and 66 respectively for normally distributed data. Therefore the sample was sufficiently large for the regression analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

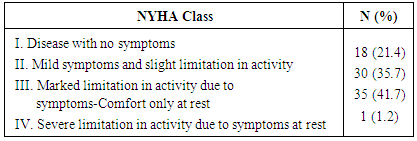

- A total sample of 84 patients with a mean age of 49 years [standard deviation (SD) 11.8 years] participated in this study. The majority of the patients were males (84.5%), married (90.5%) and employed (64.3%) (Table 1). Female patients were slightly younger (mean = 42.85 vs. 50.07, p = 0.04) than males. All patients were waiting for surgery at the hospital during the data collection, the length of waiting time ranged from 1 to 106 days. Most of the participants were diagnosed with either ischemic heart disease (IHD) (57.10%) or valve diseases (VD) (21.40%). The disease duration ranged from 1 to 456 months. The majority of the participants had not had heart surgery previously (94.0%). About 90% of the participants had medical comorbidity, with diabetes (33.30%) and hypertension (27.40%) most commonly reported in their medical records (Table 1). 20% had mild impairment of the left ventricular function, indicated by an ejection fraction of 30-49% and about 2% had severe impairment with an ejection fraction of 29% or less (Table 2). Table 3 shows that 42.9% of the patients had a NYHA classification III–IV, indicating that they experienced symptoms of fatigue, palpitations and/or dyspnea with ordinary activity or even at rest.

|

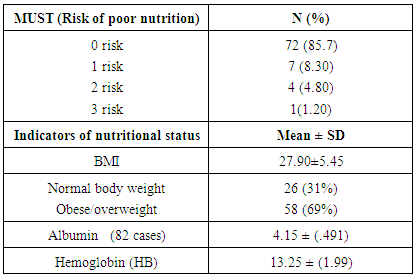

3.2. Nutritional Status

- The mean BMI for the whole group was 27.90kg/m2 (SD = 5.45). Most (69%) of the patients were obese or overweight, and 14.3% of them were at (low to high) risk of malnutrition (Table 3). The association of socio-demographic and medical data, physical health status, perceived social support, and selected indicators of nutritional status was assessed (Table not shown) as additional data. However, these results were not the focus of this study as the sample was not large enough to conduct a comparison based on the BMI classification. The results revealed that age associated negatively with albumen and hemoglobin levels. NYHA correlated positively with disease duration (r = .307, p< .002), but not with the nutritional status. BMI associated negatively with HB (-.270, p ≤ 0.05, respectively). Social support associated positively with albumin level (r = .295, p < .01); however, none of the relationships were strong (r ≤ .433). Interestingly, the length of waiting time had a significant negative association with hemoglobin and TLC (Total Leucocytes Count) (r= -.24, .20, p ≤ .04 respectively); indicating that with an increase in the length of waiting time there was decreasing in hemoglobin and TLC. Females had lower hemoglobin and TLC levels than males (p ≤ .04).

|

3.3. The Prevalence of Psychosocial Problems

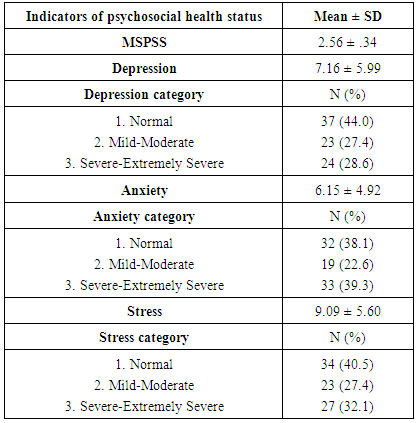

- The prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress were examined using the DASS-21, which identified that 56% of the patients suffered from depression, 61.9% suffered from anxiety and 59.5% suffered from stress, each from mild to extremely severe levels. The mean of the perceived social support was 2.56 (± SD .34), indicating that the patient's perceived social support from spouse, family and friends was high (Table 4). There was no significant difference between males’ and females’ mental health status (p ≥ .27) and perceived social support (p =.18) although females had a higher mean of depression, anxiety and stress than males. On the other hand, there was no significant association between length of waiting time and psychosocial status among these participants, although the mean score of depression, anxiety and stress of patients were waiting less than month was higher than patients were waiting more than month (7.35 vs. 7.14, 6.35 vs. 5.71 and 9.21 vs. 8.52, p ≥ .62 respectively).

|

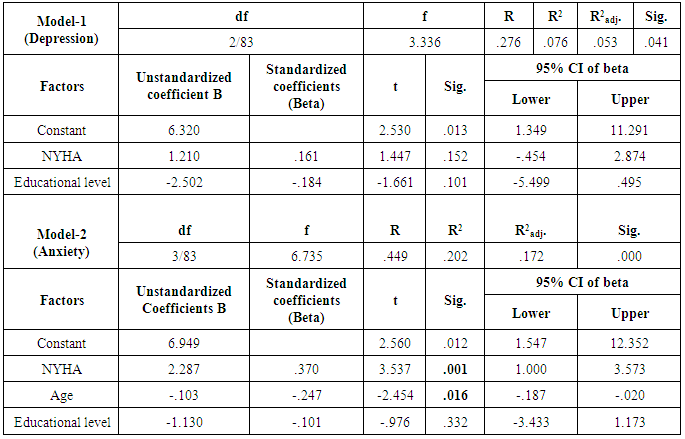

3.4. Factors Associated with the Preoperative Mental Health Status Using a Multivariable Test

- To identify factors associated with the preoperative mental health status, a correlation matrix was developed between the independent variables and the dependent variable to find variables that were significantly associated with depression, anxiety or stress. The matrix showed that the NYHA and educational levels were significantly correlated with the depression score (r = .206, -.236, p < .05 respectively). Therefore, these two variables were included in the multiple linear regression analysis to develop model-1 (Table 5). The anxiety score had a significant association with three variables: Age, NYHA and education (r = -.190, .361, -.191, p <.05 respectively); therefore, they were included in the multiple linear regression analysis to develop model-2 (Table 5). Stress was not significantly associated with any of the variables; therefore, a regression model was not developed for stress.Two models were developed to identify factors associated with depression and anxiety. Only variables that were significantly associated with them in the correlation matrix (table not shown) were entered in the models. Model-1 was developed to identify factors associated with depression. Although the model explained some variation (R = .276, R2 = .076, R2adj. = .053, p = .041) in the depression score, the two variables (NYHA and education) were not significantly associated with depression (Table 5). Model-2 was developed to find factors associated with anxiety. It could significantly explain 17.2% of the variation in anxiety (R = .449, R2 = .202, R2adj. = .172, p = .000). Two out of three Variables significantly associated with anxiety, NYHA and age (p ≤ .01). NYHA made the strongest contribution (37%, p =.001) to anxiety (Table 5).

|

4. Discussion

- To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has examined the prevalence of psychosocial health problems (depression, anxiety and stress) and associated factors as well as perceived social support among patients undergoing open heart surgery (OHS) in Egypt.

4.1. Medical Characteristics

- Similar to previous study, diabetes and hypertension were the most common reported comorbidities. Hypertension has a high prevalence in Egypt (26%) and is considered an important cause of cardiovascular diseases. Heart failure and CHD are common among hypertensive patients; the prevalence of both was 13.3% and 19.5 respectively among hypertensive patients [35]. In this study, 43% of the patients had a NYHA classification III–IV, indicating that they experienced symptoms of fatigue, palpitations, dyspnea and/or angina with ordinary activities or even at rest. A NYHA class is a commonly used method of classification and monitoring functional capacity of heart failure patients [36]. Spoladore et al. [36] found that a decrease in EF was linked to an increase in the NYHA class; although this association was not significant, it supported our findings.

4.2. Nutritional Status

- Several questionnaires, screening tools and risk indexes are available to assess the nutritional status. The screening tools and risk index (i.e. BMI, Albumen, Hemoglobin and MUST) were used in this study to assess the nutritional status of patients undergoing OHS. The BMI has been shown to be the quickest, most useful and most inexpensive measure of overweight and obesity [37]. It was selected based on its simplicity and ability to reflect fat adiposity that is positively related to body fat content [22, 38]. In our study, the mean BMI of patients was relatively high; indicating obese or overweight patients; a few of them also were at a low to high risk of malnutrition as measured by MUST. These results are similar to the reports of other studies that were conducted in Egypt [39] and elsewhere [40]. However, the risk of malnutrition was relatively higher among those patients [40] compared to our studied group. This might be because those patients were relatively older than our studied patients (mean age 74 vs. 48.95 years respectively). The risk for malnutrition was examined in this study by using ‘MUST’, which is a quick and easy tool to screen the risk for malnutrition [22]. A few of the patients had a low to high risk of malnutrition. This result is similar to a previous study [22]. It is therefore highly recommended to examine the nutritional status of hospitalized patients on their admission, in order to prevent complications, reduce the length of the hospital stay (LOS) and reduce overall costs [41].The small study sample with unbalanced nutrition groups made it hard to make comparisons between the studied patients according to their BMI and MUST classifications. Therefore, in a future study greater patient numbers with balanced groups would be necessary to overcome this limitation and find associated factors.

4.3. Prevalence of Mental Health Problems

- Abnormal depression, anxiety and stress scores were noted in over half of the patients preoperatively. Our study results are in line with previous studies in Egypt and elsewhere [17, 42-45]. In the Egyptian study, Darweesh et al. [46] observed that depression among patients with myocardial infarction, who attended outpatients for consultation, was relatively high, with about two thirds of them suffering from depression. Depression is highly prevalent among cardiac patients in general with 45% of patients with CAD having significantly depressive symptoms [42]. Most of the patients who participated in this study and also in previous studies [34] were males and employed. It is therefore likely that these patients have a lot of family and work responsibilities which may cause their depression, as well as anxious and stressful feelings. However, it might also be due to the fact that most of the participating patients were less educated and sufficient preoperative intervention or information was not given. Further research is required to test these hypotheses. In India, Vandana et al. [47] showed that patients who received preoperative information about the surgical procedure had a significantly lower preoperative anxiety score compared to uninformed patients.

4.4. Perceived Social Support

- Increased support from family, friends and significant people can facilitate the management of commonly experienced symptoms such as fatigue, emotional problems and cognitive impairment [48]. However, little is known about how patients undergoing OHS perceive their social support in Egypt; therefore it was essential to measure it. Our study's findings show that social support from spouse, family and friends as perceived by preoperative patients undergoing OHS was high and in line with previous studies [48]. Similarly, Bennett et al. [48] noted that the mean score of total support of hospitalized patients with heart failure was 56 at baseline and 53 at 12 months, indicating that these patients had moderate to high levels of perceived support. King et al. also found that the pattern of social support decreased between 4 and 12 months after heart surgery [49]. Culturally, in Egypt and elsewhere [48], the severity of the patients' health conditions may lead to increased support from the surrounding family members, particularly if the patient is hospitalized. Therefore, it was logical to find that the mean of the perceived social support was high among these patients. Because the social support may change throughout the disease trajectory [48, 49] it is essential to assess the level and types of social support preoperatively (baseline data) and postoperatively at different stages of the recovery.

4.5. Factors Associated with Mental Health Status

- Using a bivariate analysis, the results showed that NYHA and education were significantly associated with depression; but this association was not observed when those variables were entered into the regression test. This finding is inconsistent with previous studies' findings, which assessed the predictors of depression using the regression test [43, 50]. For instance, Dunkel et al. found that people being younger (≤ 65 years), lowly educated (≤ 9 years), female, and living alone were more likely to suffer symptoms of depression than other groups of patients. In the same study by Dunkel, it was noted that LVEF, dyspnea at rest, dyspnea on exertion, preoperative renal failure, many comorbidities and previous MI were independently associated with an increased risk of having depressive symptoms after adjusting for socio-demographic variables [43]. Nevertheless, our study's findings are consistent with a previous study's results [43], which noted that BMI, current smoking and employment status were not associated with the depression score. In an Egyptian study, Darweesh et al. [46] similarly observed that there was no significant difference between male and female patients. Related to the factors associated with anxiety, using the bivariate analysis test indicated that people being old, lowly educated and having low physical activity (according to NYHA) were more likely to have a high level of anxiety. When these three variables were entered into the regression model, the education correlation vanished, and only age and NYHA could explain the variation in the anxiety score. In line with previous studies, Fathi et al., [51] found that the anxiety score increased in lower educated, homeworkers, older and unemployed patients. In conclusion, other variables may contribute to the variation in the depression and anxiety scores and there is a need to explore these variables among the patients in Egypt further.

5. Recommendations

- Healthcare professionals should continually assess the nutritional and psychological health status of patients waiting for OHS to identify the patients who need extra support, and which type of support they need [52]. Interventions could be designed to decrease psychosocial distress, improve the nutritional status and either gain or lose weight. The development of a cardiac rehabilitation preoperative program that can assist patients to improve their cardiovascular physical functioning, as well as their psychological and nutritional status is required. Further care and support should be delivered to elderly patients and those who have low physical functions in order to decrease their level of anxiety. Also, further health care should be delivered to elderly people in order to improve their nutritional status during the waiting time. Further research is required to explore other factors that could explain the mental health status of these patients in Egypt. It is highly recommended to assess the nutritional and mental health status of patients throughout the first 48 hours of admission to the hospital and continue with follow up assessments to detect and manage any defect before the surgery. A longitudinal study is urgently required to examine the pattern of mental health and nutritional status preoperatively and how this links to postoperative health outcomes. There is a need to conduct a large comparison study to explore the effect of length of waiting time at hospital on physical and psychosocial health status.

6. Limitations

- It was decided to use a cross-sectional design for this study to be used mainly to generate inferences and hypotheses [20], since there is a shortage of research in this topic among these patients in Egypt. Therefore, developing causal relationships between the examined variables was impossible. The sampling method makes it difficult to generalize the study's findings, although the studied groups' characteristics are similar to those of previous studies' participants. Although the BMI can reflect a patient’s overall nutritional status, it cannot specify it precisely. Unbalanced BMI groups made it difficult to compare between these groups. Future studies are recommended with overcoming these limitations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- We are grateful to all the patients who participated in this research. We would also like to express our deep thanks to Dr. Josie Evan, reader in Public Health at the University of Stirling, UK for proofreading this research paper. Also, we would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the head of the cardiothoracic ward at ElKasr ElAini teaching hospital and all the physicians and nurses for their kind cooperation and support during the recruitment process.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML