-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2016; 6(1): 1-6

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20160601.01

Turkish Nurses’ Attitudes towards Patients with Cancer

Ozden Dedeli1, Ummu Kacer Daban2, Sezgi Cinar Pakyuz3

1Department of Internal Medicine, Celal Bayar University School of Health, Manisa, Turkey

2Department of Internal Medicine, Celal Bayar University, Hafsa Sultan Hospital, Manisa, Turkey

3Chair of Department of Internal Medicine, Celal Bayar University School of Health, Manisa, Turkey

Correspondence to: Ozden Dedeli, Department of Internal Medicine, Celal Bayar University School of Health, Manisa, Turkey.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2016 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The purpose of this study was to assess Turkish nurses’ attitudes towards cancer and patients with cancer. The study design was descriptive and cross sectional. In the three hospitals, the sample consists of 332 nurses. A questionnaire has been designed including socio-demographic and Turkish version of Attitudes Towards Cancer Scale (T-ATC). Data were expressed as mean±standart deviation (SD). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, sample t-test and multiple regression analysis. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Nurses’ total T-ATC score was 96.2±15.5 (Mean±Standart Deviation) and it showed that generally nurses had positive attitudes towards cancer patients. It was found that nurses’ positive attitudes towards cancer and patients with cancer were affected by older age, more years of nurses practice and giving care for patients with cancer. The results of this study indicated that nurses hold positive attitudes towards patients with cancer. It was suggested that the experienced and seniority nurses or specialist nurses should care for patients with cancer.

Keywords: Cancer, Attitude, Nursing

Cite this paper: Ozden Dedeli, Ummu Kacer Daban, Sezgi Cinar Pakyuz, Turkish Nurses’ Attitudes towards Patients with Cancer, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2016, pp. 1-6. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20160601.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Cancer as a disease is often associated with distressing images of treatments and of suffering and death [1]. Despite advances in cancer treatment and decreases in mortality rates, cancer is still seen by individuals, the first and foremost, as a death sentence [2]. A fear of possible impending death of their clients with cancer by health care professionals may influence their attitudes towards such clients when making contact with them. These attitudes may, on occasion, be manifested negatively towards the client by the health care professional, consequently affecting his/her behaviour towards the client’s management [3].Especially, nurses involved in caring for patients with cancer who are involved in caring for patients who are dying or have a terminal stage and are faced with the process of dying. Working with these patients and their families can be emotionally demanding and challenging [4]. Many oncology nurses describe their work as meaningful and rewarding as well as emotionally draining. Despite the emotional demand of the caring process, however, oncology nurses cite other issues as major sources of stress in their work. Organizational variables -setting, staff relationships, and available supports- are cited more often as major sources of stress. In particular, feeling inadequately prepared to meet the emotional demands of patients and their families are a significant source of stress for nurses Nurses’ attitudes towards caring for patients that are terminally ill and dying are influenced by working with these patients on a daily basis [2]. Nurses’ attitudes may be positively or negatively influenced by demographic factors (for example age and years of experience in oncology), work satisfaction and the degree of support in the working environment. If one considers that the role of caring and compassionate nursing staff has consistently been recognized as contributing to improvements in functional adjustment and quality of life of the patient with cancer. [5] The International Council of Nurses, stress that the nurses’ role is important when dealing with terminally ill patients in reducing suffering and improving the quality of life for patients and their families in the management of physical, social, psychological, spiritual and cultural needs. Nurses play an important role in developing a caring and supportive environment that acknowledges cancer in order to help patients and their family members to understand and deal with symptoms [5]. Nurses working with person who have cancer are part of society which regards the disease with fear and dread. As health professionals, they are expected to hold objective views and have the most up-to-date knowledge in order to give the best services possible to their clients. However, little is known about the attitudes of nurses working with cancer patients, in particular those working in medical and surgical wards of distinct general hospitals. Although these nurses are not expected to have specialist knowledge and skills in cancer care, they must be sufficiently informed, aware and skilled in order to give optimum care and to know when and how to refer patients to appropriate specialist services [6]. Traditionally, oncology units were among the least favored places for nurses to work in Turkey. Many general nurses have reported not wanting to work with cancer patients due to their negative view of cancer as terminal condition in addition to the comparative lack of support in general for clinical nurses in Turkey [7]. Although much has been written about attitudes toward cancer patients how the nurses would care in the clinical setting most studies have focused on only knowledge about cancer, symptom management and evidence based nursing practices [7-9]. There was no research which used valid and reliable tool for assessing Turkish nurses’ attitudes towards cancer and cancer patients. The purpose of this study was to assess Turkish nurses’ attitudes towards cancer and cancer patients.

2. Methods

- This study was conducted as a descriptive and cross sectional study. Of the five hospitals, we randomly selected three hospitals in Manisa Center, Turkey. These hospitals were University Hospital, State Hospital and Private Hospital. A sampling technique was used to recruit nurses from three hospitals. There were a total of 688 nurses in these three hospitals. Participants were selected according to the following criteria; who had been 18 years of age and over 18, able to speak and read Turkish, to be willing participant. The study subjects included 150 nurses (45.8%) in University Hospital, 155 nurses (43.1%) in State Hospital, 27 nurses (11.1%) in Private Hospital. The study purpose, procedural details, the participant’s rights and potential benefits and risks of the study were explained and written consent forms were obtained from them.

2.1. Instruments

- Data were collected by using Turkish version of the Attitudes Towards Cancer Scale (T-ATC) and a demographic instrument, which took a range from 20 to 30 minute.A demographic instrument: A questionnaire was composed by the authors to capture personal information on age, gender, department, marital status, participation in scientific meeting and in-service training about cancer.Turkish Version of the Attitudes Towards Cancer Scale: The Attitudes Towards Cancer Scale (ATC) was initially developed by Tichenor and Rundall (1977). ATC is used in Likert format and it consists of 30 statements expressing both positive and negative sentiments about a person with cancer [10]. Turkish version of the ATC scale (T-ATC) was tested the reliability and validity by Kacer et al (2014) that can be used in Turkish speaking countries in order to measure attitudes towards cancer and patients with cancer. T-ATC consisted of 30 items with six responses (+1, +2, +3, -1, -2, -3) for each statement. The items were scored in such a way that a score of +3 indicated strong agreement and that of -3 indicated strong disagreements with statement. There was no neutral or zero point provided on the scale, so the respondent had to indicate to some extent either agreement or disagreement with each item. The mean scores of the T-ATC are 95.5±14.3 (Mean±Standart Deviation). Higher scores indicate more positive attitudes towards patients with cancer. Alpha coefficient is 0.68 [11]. In the present study, alpha coefficient was found 0.79 for the T-ATC.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

- The data were analyzed using The SPSS for Windows Version 16.0. Data were given as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and percentage (%). Independent sample t-test was used to examine difference between gender, marital status, job satisfaction, in-services training about cancer, and participation in scientific meeting about cancer according to the T-ATC scale. One-Way ANOVA was used to evaluate difference among age groups, educational status, status of giving care for patients with cancer, and working years according to the T-ATC scale. The T-ATC scale was applied to multiple regresyon analysis as the criterian variable yielded independent variables (i.e., sociodemographics factors). A two-tailed p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

2.3. Ethical Consideration

- This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Celal Bayar University Faculty of Medicine at Manisa, Turkey. In addition, local health authority in Manisa gave written permission for conducting research. Participants were informed that they could refuse or withdraw from the study at any time. Participants signed a consent form before questionnaires were administered.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

- Of the 332 nurses, 290 were women, the majority of whom was married (62.7%). The average age of the nurses was 31.9±7.2 years. The demographic and other characteristics of nurses are shown in the Table 1.

|

3.2. Nurses’ Attitudes toward Cancer and Cancer Patients

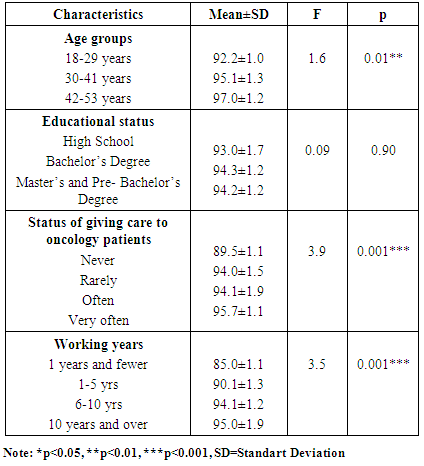

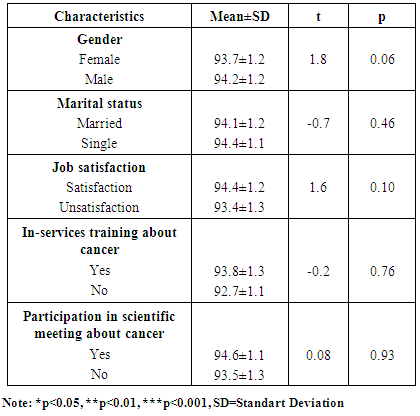

- Nurses’ total T-ATC score was 96.2±15.5 (min = 44.0 - max=143.0). Table 2 presents relationships between nurses’ total T-ATC score and demographic characteristics. There were statistically significant relationships between nurses’ total T-ATC score and age groups, working years, status of giving care for patients with cancer (respectively, p<0.01, p<0.001 and p<0.001), but there was no significant relationship between nurses’ total T-ATC score and gender, marital status, educational status, job satisfaction, in-services training about cancer and participation in scientific meeting about cancer (p>0.05) (Table 3). That is, nurses’ positive attitudes towards cancer and patients with cancer were affected by older age, excess of working years and giving care for patients with cancer, but it was not affected by gender, marital status, educational status, job satisfaction, in-services training about cancer and participation in scientific meeting about cancer.

|

|

4. Discussion

- Cancer is a chronic disease that symbolizes the death and distinguishes the limits of our control in life while causing many psycho-social problems with much inconveniency in daily routine. These psycho-social problems do not only affect the patients but also their families. It affects the health care professionals who involved with the curing and treatment of the patients too. Especially nurses those who are involved with the chronic and fatal diseases such as cancer may be under a great risk of developing negative attitudes [12]. Demmer (1999) stated that talking about death and dying with patients and family members is an ongoing challenge for nurses. This issue has been described as the most difficult aspects of care by nurses while caring for patients who were dying. Moreover, it was found that nurses’ attitudes towards patients who were dying were negative affected by these negative experiences [13]. Astrom et al (1994) reported from her study that nurses who had negative experience with patients tended to expect negative outcomes with patients [14].The negative or positive attitudes toward cancer and cancer patients in the health care services have almost appeared, regarding recent studies. Some health professionals are likely to have negative attitudes toward patients with cancer. The personal beliefs and attitudes of nurses can have serious implications for their practices [6, 14, 15, 16]. Few studies have examined Turkish nurses’ attitudes towards patients with cancer [7, 17]. In the current study, we aimed to assess Turkish nurses’ attitudes toward cancer and patients with cancer. The results from this study indicated that Turkish nurses hold positive attitudes towards cancer and patients with cancer. Nurses’ positive attitudes towards cancer patients could be evaluated satisfaction for nursing care and positive outcomes of patients. In the study by Yildirim-Usta et al (2012) the nurses were aware of their attitudes towards being positive with cancer patients and its significance in support for cancer patients [7]. Terakye (2011) stated that many Turkish nurses describe their work with cancer patients as meaningful and rewarding as well as emotionally draining [17]. Adversely, several researches demonstrated that health care professionals hold negative attitudes towards patients with cancer [1, 16, 18]. Nurses’ attitudes towards cancer patients that may be influenced by the demographic factors such as age, workplace and years of experience in oncology, degree of work satisfaction5, gender, profession and clinical experience or specialist education [18], oncology course, medical education about oncology [19] a workshop or a seminar on cancer [20]. In the current study, significant relationships were observed between nurses’ attitudes toward cancer and patients with cancer and age, working years and status of giving care for patients with cancer. This could indicate that nurses whose ages were 40 years and over also working years were 10 years and over, and had experiences in caring for patients with cancer, had more positive attitudes. The results were supported by a multiple regression analysis. Indeed, it would seem that nurses’ attitudes towards patients with cancer are more strongly developed by professional experiences. Similar to our findings, the research of Elkind (1981) and Elkind (1982) stated [21, 22] that nurses’ personal and professional cancer experiences, specialist education and seniority as mediating negative attitudes in a positive direction. As in Lange et al.’s (2008) study [6], oncology nurses have more positive attitudes towards death and caring for dying patients than another health care professional. It was found to be there was statistically significant correlation between positive attitudes and age, duration of working in oncology clinical, working years. Our results of study contrast the work of Corner (1993), who found that professional experience acted to reinforce or increase already nurses’ negative attitudes. Corner (1993) interviewed 127 cancer nurses about their attitudes toward cancer and caring for patients with cancer. The most commonly occurring theme was a feeling of inadequacy and lack of preparation for their role in cancer care. The greatest area of concern was feeling an inadequacy in giving psychosocial care and in communicating with patients. Nurses experienced the greatest difficulty in answering patients' questions and determining how much information they were allowed to give to the patients [16].In the current study, it was no significant relationships between nurses’ attitudes and their educational status, gender and marital status. As like Kearney et al (2003) stated [18] that oncology health care professionals hold negative attitudes towards cancer and changing these attitudes presents a significant challenge. No statistically significant difference was detected between gender and specialist education. We detected that no significant relationships exist between nurses’ attitudes and their educational status, in-services training about cancer, participation in scientific meeting about cancer. Lebovits et al (1984) compared [19] the attitudes of medical students towards cancer before and after undertaking an oncology course and with students who did not participate in the programme. They found that those students participating in the course were more positive towards the out-patient functioning of patients with cancer and also less pessimistic towards the disease than those students who had not participated. Based on these findings they believed that early medical education in oncology, alongside contact with ambulatory patients with cancer, can positively influence attitudes towards cancer. Corner & Wilson-Barnett (1992) compared [20] the effects of a workshop, seminar or no intervention on newly qualified nurses' attitudes towards cancer. Evaluation using a cancer attitude scale showed no difference in attitudes while data from open-ended, semi-structured interviews showed greater optimism and sophistication regarding nurses' perception of patients' ability to cope psychologically with a cancer diagnosis in the group who had participated in the workshop. This led the authors to presume that the attitude scale was not particularly sensitive to attitude change.The findings of our study indicated that no significant relationships exist between nurses’ attitudes and their job satisfaction. In contrast, deKock (2011) stated [5] that oncology nurses’ attitudes towards caring for patients that are dying, to determine the degree of work satisfaction experienced by these nurses, to determine the perceived supportive nature of their work environments, and to establish and examine any relationships between oncology nurses’ attitudes towards caring for patients that are dying and work satisfaction and a supportive work environment. The nature and quality of cancer nursing care depends on a number of factors including personal characteristics of nurses, their knowledge and skills, resources, support and clear and relevant policies. One of the most important personal characteristics which can affect nursing care in any setting is the attitude of nurses. Nurses’ attitudes and beliefs about cancer patients can have serious implications for their practices. The knowledge and skills they require must be underpinned by the kind of attitudes that will ensure that their patients receive the best possible care. We found that nurses who had less experiences and more young hold negative attitudes toward cancer patients. In addition, nurses who cared for cancer patients more frequently they hold more positive attitudes towards cancer patients. This could indicate that nurses who having experience alone with cancer clients was sufficient to promote positive attitudes. It is important that nurses' personal and professional experience of cancer patients contribute towards a balanced and informed view of the disease and treatments.

5. Conclusions

- The care of patients with cancer has been explored in the nursing literature, with studies focusing on caring for the patient throughout diagnosis, treatment, possible recurrence, palliative care, and more recently, survivorship. Most of this research has focused on the experiences of oncology trained nurses and those working in specialist cancer units. However, very little attention has been paid to the experiences of generalist or non-specialist nurses when caring for patients with cancer on medical and surgical units. Despite of these limitations, results of this study demonstrated Turkish nurses hold positive attitudes towards patients with cancer. The results from this study indicate that the positive attitudes towards patients with cancer held by Turkish nurses replace by are significant regarding to age, status of giving care to oncology patients, working years. Nevertheless, this study provides evidence the attitudes towards cancer and cancer patients among nurses. Therefore, further studies confirm that our results are recommended. Our findings suggested that the T-ATC should be tested in other population (health professionals, public, etc.) in the way of attitudes towards cancer and cancer patients.

6. Recommendations

- Our research is the first study that has been performed in Turkey, to assess Turkish nurses’ attitudes toward cancer and patients with cancer. However, the current study has limitations. The first limitation of study was conducted only nurses. The second limitation was that this study was performed in Manisa, Turkey (West Anatolian).The results of this study indicated that nurses hold positive attitudes towards cancer and patients with cancer. Having more experience along with cancer patients and having seniority were promoting positive attitudes. Nurses’ attitudes plays important role in cancer patients’ efficient use of systems for coping with the treatment and coping with complications that could be posed by the disease or other treatment modalities such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy. It was suggested that the experiences and seniority nurses or specialist nurses should care for patients with cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- We would like to thank Chief of Medicine of Celal Bayar University Hafsa Sultan Hospital, Turkey Ministry of Health General Secretary of Manisa Association of Public Hospitals, and nurses who participated in.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML