-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2015; 5(4): 131-135

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20150504.02

Nursing Guidelines for Children Suffering from Beta Thalassemia

Lamiaa Ahmed Elsayed1, Sahar Mahmoud El-Khedr Abd El-Gawad2

1Pediatric Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Ain shams University, Egypt

2Pediatric Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt

Correspondence to: Sahar Mahmoud El-Khedr Abd El-Gawad, Pediatric Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Thalassemia is heterogeneous hereditary anemia characterized by a reduced output of β-globin chains. It affects approximately 4.4 of every 10,000 live births throughout the world. Treatment with a regular transfusion program and chelating therapy, aimed at reducing the transfusion iron-overload. Managements allows for normal growth and development, extends the life expectancy into the third to fifth decade. Oral iron chelatorsdeferiprone has led to reduced morbidity, increased survival and improved quality of life. Bone marrow transplantation has offered a definitive cure for the fraction of patients with available donors. Children with thalassemia have fewer circulating red blood cells than normal and make less hemoglobin that results in anemia. Pediatric nurses set guidelines for providing high-quality nursing care for children suffering from thalassemia and establish criteria for evaluating the care provided to those children. Such guidelines help assure children with thalassemia, are receiving high-quality care. Developing Guidelines for caring of children suffering from thalassemia include combining four strategies including education, carrier screening, counseling and prenatal diagnosis. So, this article aimed to establish guidelines for children suffering from beta- thalassemia.

Keywords: Nursing Guidelines, Children & Beta Thalassemia

Cite this paper: Lamiaa Ahmed Elsayed, Sahar Mahmoud El-Khedr Abd El-Gawad, Nursing Guidelines for Children Suffering from Beta Thalassemia, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 5 No. 4, 2015, pp. 131-135. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20150504.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Thalassemia is an inherited autosomal recessiveblood disorder characterized by abnormal formation of hemoglobin. This results in improper oxygen transport and red blood cells destruction. [1] Thalassemia is caused by missing genes that affect how the body makes hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen. Children with thalassemia have fewer circulating red blood cells than normal and make less hemoglobin, that results in microcytic anemia.Complications of thalassemia include, iron overload, bone deformities, and cardiovascular diseases. In that respect, the various thalassemias resemble another genetic disorder affecting hemoglobin, sickle-cell disease. [2, 3] Thalassemia resulted in 25,000 deaths in 2013 down from 36,000 deaths in 1990. [4] It affects approximately 4.4 of every 10,000 live births throughout the world. Both males and females inherit the relevant gene mutations equally. Approximately 5% of the worldwide population has a variation in the alpha or beta part of the haemoglobin molecule, although not all of these are symptomatic and some are known as silent carriers. In fact, only 1.7% of the global population has signs as a result of the gene mutations, known as a thalassemia trait. [5]Thalassemia is a heterogeneous group of hemoglobin production disorders that is primarily found in the Mediterranean, Asian, Indian, and Middle Eastern regions. These regions account for 95% of all thalassemia births in the world. The epidemiology of thalassemia, however, is rapidly evolving due to migration patterns. [6] Beta Thalassemia is the most common chronic hemolytic anemia in Egypt (85.1%). A carrier rate of 9-10.2% has been estimated in 1000 normal random subjects from different geographical areas of Egypt. The life expectancy and the quality of life of thalassemics remarkably improved over the last 9 years after the development of different centers for their management and care but still they have the problem of hepatitis C which is 76.7%. [7] In Egypt there are 10,000 registered thalassemia cases and more than 20,000 non-registered cases. 95% are beta thalassemia major; 5% are thalassemia intermedia or hemoglobin H disease. Trait carrier rate ranges between 5.5% to > 9.5% based on a study carried out on 5000 normal candidates in 5 governorates in Egypt. [8]

2. Overview of Thalassemia

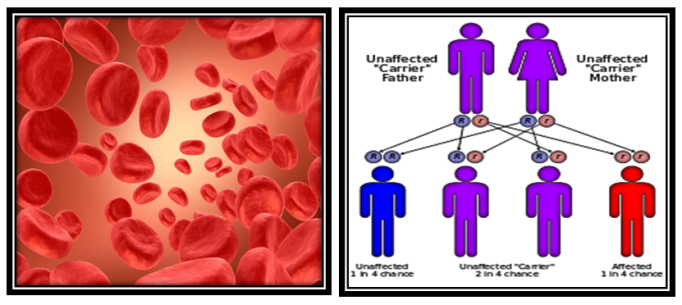

- Thalassemia is a group of inherited blood disorders. It is an inherited diseases passed on through the genes of parents. There are two kinds of proteins that produce hemoglobin, called alpha protein and beta protein. A person with alpha thalassemia doesn't have enough alpha protein; a person with beta thalassemia doesn't have enough beta protein. Beta thalassemia disorders result from decreased production of beta globin chains, resulting in relative excess of alpha globin chains. The degree of excess nonfunctional alpha chains is the major predictor of disease severity. [9]

| Figure 1. |

3. Common Definitions Used in Thalassemia

- Beta thalassemia refers to the absence of production of beta globin. When patients are homozygous for a beta thalassemia gene, they cannot make any normal beta chains (hemoglobin A). Beta thalassemia major is a clinical diagnosis referring to a patient who has a severe form of the disease and requires chronic transfusions early in life. Beta thalassemia intermedia is a clinical diagnosis of a patient characterized by a less severe chronic anemia and a more variable clinical phenotype. Alpha thalassemia refers to a group of disorders characterized by inactivation of alpha globin genes. This results in a relative increase in nonfunctional beta globin or gamma globin tetramers and subsequent cell damage. Normally, there are four alpha genes. Absence or non-function of three alpha genes results in hemoglobin H disease, and the loss of all four alpha genes usually results in intrauterine death. [10]Thalassemia is a genetic disorder that involves the decreased and defective production of hemoglobin, a molecule that's found inside all red blood cells and is necessary to transport oxygen throughout the body. There are two types of thalassemia: alpha-thalassemia and beta-thalassemia, .the Beta thalassemia is one of the commonest recessive genetic diseases that results in a severe anemia. Therefore, children with ß- thalassemia major need regular blood transfusions in order to live. [11, 12]Thalassemia is a genetic blood disorder which can be fatal if proper treatment is not received. Blood transfusion therapy is the mainstay of treatment, and needed for children with thalassemia to live. Diminished quality of life, uncertainties over the entire lifespan, and disruptions to the family system are the outcomes of an illness. [13] In this regard, children with thalassemia major have good survival but little is known about their quality of life. Therefore, It is important to provide efficient educational support regarding thalassemia for the children can raise their awareness, and can help to improve their quality of life. [14]

4. Pathophysiology of Beta-thalassemia

- βeta-thalassemia syndromes reflect deficient β-globin synthesis usually owing to a mutation in the βeta-globin locus. The relative excess of α-globin results in the formation of insoluble aggregates leading to ineffective erythropoiesis and shortened red cell survival. A relatively high capacity for fetal hemoglobin synthesis is a major genetic modifier of disease severity, Iron overload secondary to red cell transfusions causes an increase in liver iron and leading to endocrine and cardiac dysfunction. [15, 16]The thalassemias are inherited disorders of hemoglobin (Hb) synthesis. Their clinical severity widely varies, ranging from asymptomatic forms to severe or even fatal entities. Beta-thalassemia is due to impaired production of beta globin chains, which leads to a relative excess of alpha globin chains. These excess alpha globin chains are unstable, incapable of forming soluble tetramers on their own, and precipitate within the cell, leading to a variety of clinical manifestations. The degree of alpha globin chain excess determines the severity of subsequent clinical manifestations, which are profound in patients homozygous for impaired beta globin synthesis and much less pronounced in heterozygotes who generally have minimal or mild anemia and no symptoms. [15, 16]Alpha thalassemia, in comparison, is due to impaired production of alpha globin chains, which leads to a relative excess of beta globin chains. The toxicity of the excess beta globin chains in alpha thalassemia on the red cell membrane skeleton appears to be less than that of the excess partially oxidized alpha globin chains in beta thalassemia. Unbalanced alpha globin chain synthesis leads to hemolysis of red cells in the peripheral circulation and, more importantly, to the extensive destruction of erythroid precursors within the bone marrow and in extra medullary sites, such as the liver and spleen (ineffective erythropoiesis. [16, 17]

5. Clinical manifestation for children with Thalassemia

- The clinical picture that appear on children suffering from thalassemia varies widely, depending on the severity of the condition and the age at diagnosis. Signs and symptoms of different types of thalassemia include the following:1. Pallor, slight sclera icterus, enlarged abdomen. [18]2. Severe hemolytic process 3. Β-Thalassemia: Extreme pallor, swollen abdomen due to hepato-splenomegaly4. Bone deformities: Severe bony changes due to ineffective erythroid production (eg, frontal bossing, prominent facial bones, dental malocclusion). [19]

| Figure 2. |

6. Management of Thalassemia

- Children with thalassemia traits do not require medical or follow-up care after the initial diagnosis is made. [22] People with β-thalassemia trait should be warned that their condition can be misdiagnosed as the more common iron deficiency anemia. They should avoid routine use of iron supplements. [23] Children with Severe thalassemia, require medical treatment. Blood transfusion was the first effective measure thus prolonged life. [22] Multiple blood transfusions can result in iron overload. Iron overload can be treated by chelation therapy, that resulted in improved life expectancy in those with thalassemia major. [24]Bone marrow transplantation (BMT) may offer the possibility of a cure in young people who have an Human Leukocytes antigen matched donor. [25] The success rates of BMT ranged between 80–90% range, while mortality rate is about 3%. [25] There are no randomized controlled trials which have tested the safety and efficacy of non-identical donor bone marrow transplantation in persons with β-thallassemia who are dependent on blood transfusion. [26] If the person does not have an HLA-matched compatible donor, another method called bone marrow transplantation (BMT) from haploidentical mother to child (mismatched donor) may be used. In a study of 31 people, the thalassemia-free survival rate 70%, rejection 23%, and mortality 7%. The best results are with very young people. [27]

7. Standardized Nursing Guidelines

- The nurse plays a vital role in the care of patients with thalassaemia.. It is therefore of the utmost importance to have a nursing service that is integrated, seamless and suitable for patients in both the acute and community setting, irrespective of what part of the world they are in.Nurses are also essential in helping children to become aware in their own condition, teaching effective techniques for self-management, the prevention of complications and the transition of pediatric patients to the adult team of healthcare specialists, as well as in genetic counseling. [28]The pediatric nurse is an essential element in the successful management of thalassaemia. Nurse specialists provide experienced, skilled support and encouragement throughout an often standardizes treatment regime. The nurse who knows the patient, family and their social situation intimately is uniquely placed to provide an indispensable link between the haematologist, the patient and other health professionals and essential services. The nurses provide an optimum level of care. [29]Developing Guidelines for caring of children suffering from thalassemia include combining four strategies including education, carrier screening, counseling and prenatal diagnosis. The need for effective health service structure co-operation, adequate education of responsible health professionals, although thalassemia cannot be prevented, it can be identified before birth by prenatal diagnosis. [17, 30] Nurses can play a critical role in the wellbeingand quality of life of children. In particular, nurses should be sure that patients are educated about their disease and about the treatment options available. Children suffering fromlong-term conditions require continuing support and nursing care throughout their lives. The nursing care of the child with thalassemia is primarily aimed at supporting the child and their families for minimize the effect of illness. [14]Pediatric Nurse practitioner are trained to treat children with thalassemia, meet their specific needs and counsel all family members on preventive treatment measures and serious complications. Pediatric nurse practitioner evaluates every child with thalassemia during visits for their routine transfusions under the supervision of a hematologist. A nurse provides continuing education and monitors compliance with chelation therapy. They also, provides support regarding the diagnosis and therapy, and identifies all necessary resources for the family. [17]

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML