-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2015; 5(1): 5-19

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20150501.02

Effective Characteristics of a Clinical Instructor as Perceived by BSU Student Nurses

Rencel Finnos V. Sabog, Lawrence C. Caranto, Juan Jose T. David

College of Nursing, Benguet State University, La Trinidad, Benguet, Philippines

Correspondence to: Rencel Finnos V. Sabog, College of Nursing, Benguet State University, La Trinidad, Benguet, Philippines.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2015 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This article is a report on a study conducted to explore the effective characteristics of a clinical instructor as perceived by student nurses. Specifically, it aimed to: (1) determine if a significant difference exists on students’ perceptions of the effective characteristics of clinical instructors when grouped according to academic level and sex; (2) identify the top ten (10) effective characteristics as perceived by student nurses; (3) determine which subset among the five (5) domains of characteristics was deemed most important by student nurses; and (4) establish why student nurses have such perceptions on clinical instructor characteristics. Clinical faculty members have a significant role in the education and development of nursing students. Despite the many studies conducted regarding clinical teaching behaviours, a gap still exists regarding the topic of clinical teaching effectiveness. Exploration of effective characteristics expected from clinical instructors may provide insights to further improve educational programs for student nurses. The study utilized a mixed-method design. Quantitative data were collected by administering questionnaires to 224 student nurses in January 2015. Questions were asked to measure the importance of each of the thirty (30) effective clinical instructor characteristics enumerated. Results were subjected to several statistical measures using the SPPS version 21 (IBM Corp., 2011). Qualitative data, on the other hand, were gathered by conducting 32 key informant interviews to answer the last objective. It was deduced that sex is not a variable in student nurses’ perceptions of effective clinical instructor characteristics. Conversely, it was established that difference in academic level poses an effect in students’ perceptions of the identified characteristics. Professional competence is deemed to be the most important characteristic among the five (5) domains. It was supported by the inclusion of three (3) competence-related clinical teaching behaviours in the upper half of the roster. By and large, characteristics pointed out by the students during the interviews are clinical teaching behaviours that help them bridge the gap between theory and practice. It was concluded that generally, CIs need both character and competence when aimed at gearing student nurses to become successful members of the profession.

Keywords: Effective, Perceptions, Clinical instructor characteristics, Student nurses

Cite this paper: Rencel Finnos V. Sabog, Lawrence C. Caranto, Juan Jose T. David, Effective Characteristics of a Clinical Instructor as Perceived by BSU Student Nurses, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 5 No. 1, 2015, pp. 5-19. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20150501.02.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Health care education curricula are first and foremost divided into two components: didactic and clinical. Customarily, the didactic bit involves the usual 4-walled setting type of learning. Meanwhile, the clinical aspect paints the picture of students applying into practice the theories they have understood in the classroom. Furthermore, it aims to develop and imbue students with professional competencies necessary for them to be apt in the world of health care. Taken as a whole, it is geared towards crafting confident, independent and unwavering student nurses (Elcigil & Sari, 2007) [1].The clinical education, regardless of the profession or setting, is a process that has been studied from various points of view to establish better learning objectives (Tiwari, Rose, and Chan, 2005) [2]. Laurent and Weidner [3] (2001) pointed out that it is employed by diverse professions as a mode to carry out didactic models in a practical milieu. In addition, Shen and Spouse [4] (2007) have claimed that mentorship is an important resource for student; a well-functioning student–mentor relationship supports students’ and nurses’ professional development. Hence, it is imperative that nurses who take the mentor role should have special qualities to be able to professionally develop student nurses’ competence in the nursing practice while they are still in the academe.Clinical faculty members have a significant role in the education and development of nursing students. Investigation of effective characteristics expected from them provides insight into improvement of educational programs for developing nurses. Therefore, it is useful to identify characteristics that lead to highly effective skills and techniques of those in instructional roles. Primarily, the purpose of this study was to identify the perceptions of Benguet State University – College of Nursing student nurses of clinical faculty traits that are most beneficial to student learning outcomes.Specifically, the research aimed to: determine if a significant difference exists on students’ perceptions of the effective characteristics of clinical instructors when grouped according to academic level and sex; identify the top ten (10) effective characteristics as perceived by student nurses; determine which subset among the five (5) domains of characteristics was deemed most important by student nurses and give light on why student nurses have such perceptions on clinical instructor characteristics.The independent variables in the study are the respondents’ sex and year level. The dependent variables, on the other hand, are the student nurses’ perceptions on the effective clinical instructor characteristics.This study may advance clinical nursing education by contributing information utilizing students’ individual perceptions of an effective clinical instructor. Students’ views of the effectiveness of the preceptors’ behaviours are important indicators to modify and facilitate effective clinical instruction. At present, studies regarding students’ perspectives of how an effective clinical instructor should be like are limited, especially in the Philippines. Results may assist faculty to appreciate students’ views and compare it with their own perceptions. As a result, they may become aware of those characteristics of success to reinforce them, as well as those that need improvement.

2. Background

- Using exploratory descriptive techniques, Kelly [5] (2006) explored which clinical teaching behaviours and contextual influences affect student learning. An overwhelming amount of data indicating “teacher knowledge” as the highest student rated category for effectiveness was found. Characteristics from this category cited by students as effective included “application of theory and clinical experience of instructors” and the “instructor’s ability to apply material to real life learning situations.” Students rated feedback as the second highest category citing the need to have timely feedback on tasks, teacher availability, and teacher’s allowing students to have time to state their own views. Students also emphasized the need to have privacy when receiving praise or constructive criticism. Furthermore, they have voiced concerns about the importance of clinical site, citing staff incivility as a major concern. Meanwhile, Ali and Phelps [6] (2009) revealed that nursing students have common and unique perspectives on the importance of a clinical instructor demonstrating effective characteristics. Personality traits ranked lowest (72.6%) while knowledge and experience topped the list of the most important effective characteristics of a clinical instructor from students’ point of view. Furthermore, Kube [7] (2010) reported teaching behaviours demonstrated by clinical instructors and most frequently perceived by nursing students as influencing student learning. The teaching behaviours reflecting positive influence on student learning are as follows: (a) approachable, (b) appears organized, (c) provides support and encouragement, (d) provides frequent feedback, (e) well prepared for teaching, (f) encourages mutual respect, (g) listens attentively, and (h) makes suggestions for improvement. In 2010, Heshmati-Nabavi and Vanak [8] identified five key features of effective clinical educators: (1) personal traits; (2) meta-cognition; (3) making clinical learning enjoyable; (4) being a source of support and (5) being a role model. They concluded that effective clinical instructors are those who are in synchronization with students and act as a role model for students and patients. Using quantitative research method, Girija et al. [9] (2013) revealed that both male and female Omani nursing students rated professional competence of instructors as the most important characteristic. Students ranked the first five most effective clinical instructor characteristics as followed: objective evaluation, role modelling, clinical competence, communication skills, and respecting students’ individuality. A more recent study by Al-Hamdan et al. [10] (2014) concluded that a mentor has a major influence on students’ drive to learn and their capacity to adjust to new conditions. Mentors’ activities and qualities play a vital role in the clinical teaching and students’ education. Successful development of nursing students into a professional role as caring nurses is increasingly believed to be dependent on the quality of the clinical learning environment (Hofler, 2008) [11]. Conversely, perceptions of unfair treatment by nursing faculty lead to student nurses voicing their concerns, leaving the program or conforming to the situation to avoid being failed (Thomas, 2003) [12]. Although such a relationship has been claimed to form the basis for student–teacher connection and to be a positive influence on students’ learning outcomes, there is a paucity of research exploring these claims (Gillespie, 2002) [13].

3. Methods

3.1. Design

- The study employed the mixed method research design which involves both quantitative-descriptive and the qualitative designs.

3.2. Sampling

- It included student nurses currently enrolled in Related Learning Experience at the College of Nursing, Benguet State University. This guarantees that the respondents have experienced assessing teaching behaviours of clinical instructors in the clinical setting and during return demonstration. Random sampling was utilized to have an equal representation of the different academic levels.

3.3. Instrument

- For the quantitative section, a self-reporting survey was utilized. This method was employed because of its ability to collect a large amount of information from many participants using only one instrument, as Portney and Watkins [14] (2008) pointed out.The survey instrument utilized in the study was a modified version of the Effective Clinical Instructor Characteristics Inventory (ECICI) developed by Girija et al. [9] (2013) previously revised by Alasmari [15] in February 2014. Some inputs were taken from an older tool, the Clinical Teaching Evaluation instrument, developed by Dr. Fong (Fong & McCauley, 1993) [16]. This instrument was selected for use in relation to the content it encompassed. A brief demographic survey of the population was included in Section I of the questionnaire to determine the academic level and sex of the respondents. The instrument included thirty (30) clinical teaching behaviours in Section II in which subjects rated in terms of importance using a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 4 - Very Important to 1 – Not Important. Validity and reliability were established by review of the College Dean, Chair of the Department of Clinical Instruction, three (3) nursing faculty members and two (2) counsellors from the university’s Office of Student Services. A tool lifted from Garambas [17] (2010) was provided to the said experts in validating the questionnaire. The resulting overall mean from the tally was 4.67 (excellent), indicating that the data gathering tool was valid and reliable.Meanwhile, comprehensive criterion sampling was utilized for the qualitative portion. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with thirty-two (32) key informant Level IV student nurses. Qualitative data were drawn only from the fourth year students considering that they are the most experienced when it comes to clinical practice. For the same reason, they have more information regarding effective clinical teaching behaviours, as they have been through more years assessing their clinical instructors.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

- Participation in the study was strictly voluntary with implied consent assumed with return of the completed survey. For the interviews, volunteerism was assumed when the respondent agreed prior to the interview process. Meanwhile, there were no risks identified for being included in the study. Benefits from the study cover the identification of effective characteristics of clinical instructors which may provide a positive effect on student learning outcomes in the clinical setting.

3.5. Statistical Treatment

- The quantitative data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20 [18] (IBM Corp., 2011). T-test was utilized to determine if a significant difference exists between the male and female’s perceptions of the effective characteristics included in the data gathering tool. Meanwhile, F-test was utilized to identify the differences in students’ perceptions when grouped according to their academic levels with Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference Test utilized as a post-hoc analysis treatment. The data were subjected to post-hoc treatment to determine which populations differed significantly in the results. To identify which characteristics belong to the top ten (10) amongst the thirty (30) clinical teaching behaviours, arithmetic mean, standard deviation, and ranking were used. In mean scores, higher scores implied more important characteristics.The same descriptive statistics were used to establish the ranking of the five (5) domains. On the other hand, the qualitative data were analyzed thematically. A thematic analysis is one that looks across all the data to identify the common issues that recur, and identify the main themes that summarize all the views one has collected (Brikci and Green, 2007) [19]. Data were transcribed and were coded, accessing significant statements anchored on the topics addressed.

4. Results and Discussion

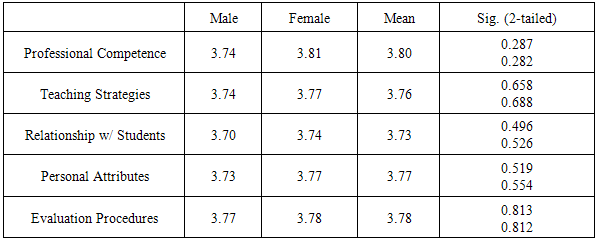

4.1. Perceptions of the Characteristics of Male and Female Student Nurses

- The author explored which clinical teaching behaviours and contextual influences affect student learning in the area. Table 1 shows that there is no significant difference between male and female student nurses’ perceptions of the effective clinical instructor characteristics. The results coincided with the study of Girija et al. [9] (2013) wherein most of the categories were not significantly different when sex was considered. However, for the category relationships with students, a significant difference (p = 0.034) existed whereby females rated it higher than male students.

|

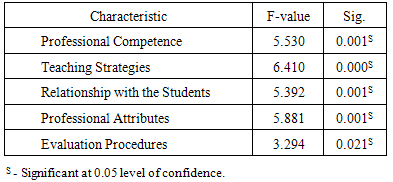

4.2. Difference in Perceptions of the Characteristics among the Different Year Levels

- Table 2 points that there is a significant difference among the respondents’ view of the effective clinical instructor characteristics when grouped according to year level in contrast with Girija’s study [9] which showed no statistical difference.

|

|

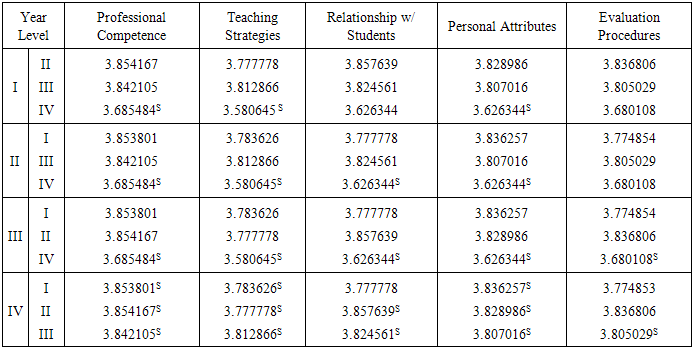

4.3. Difference in Perceptions of the Characteristics among the Different Year Levels

- Table 4 highlights the top ten characteristics ordered in descending importance. On average, the characteristic ‘respects student as an individual’ was noted to be the most important by the respondents. The result is in alignment with Ali’s study [21] (2012) which claimed that student nurses perceived clinical instructors’ caring behaviours in several ways which include the particular characteristic being discussed. It has been postulated that clinical instructors must possess caring behaviours such as the abovementioned if they want to facilitate students' entry and learning in a multifaceted world of clinical practice (Ali, 2012) [21].

|

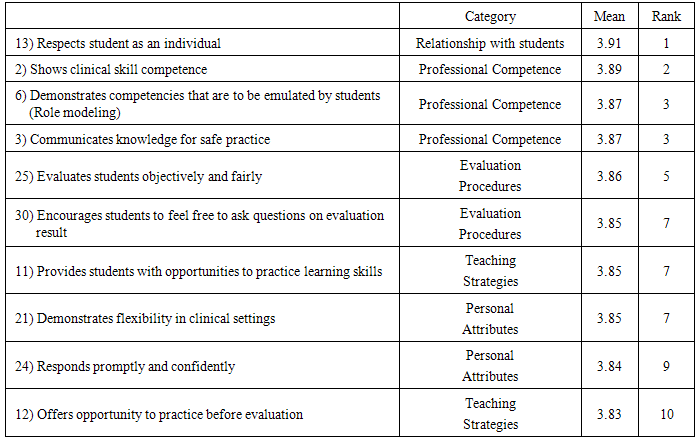

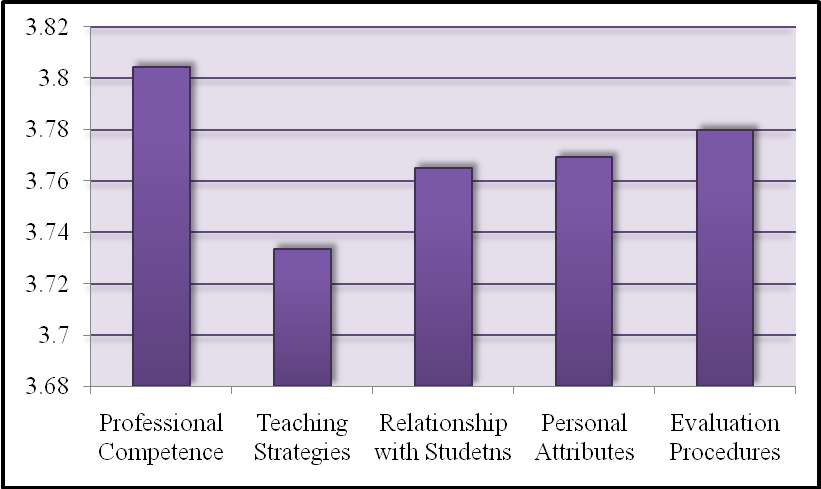

4.4. Comparison of the five (5) Domains of Effective Clinical Instructor Characteristics

- Figure 1 discloses that the most important effective clinical instructor domain is professional competence. This is in agreement with several studies whereby the same subset was rated with the highest importance. Girija (2013) [9] concluded that nursing students value clinical instructors’ professional competencies as the most important characteristic. Despite changes in curriculum and teaching methods and the wide-spread dependence on the internet as source of knowledge, nursing students depend primarily on their mentor as a source of knowledge (Al-Hamdan et al., 2014) [10]. The authors claimed that accurate knowledge and competent clinical skills had the highest mean and median for the participants in three countries, indicating that it is the most important quality that students like to see in their mentor.

| Figure 1. Comparison of the Five (5) Categories of Effective Clinical Instructor Characteristics |

4.5. Effects of Instructors’ Clinical Teaching Behaviours on Student Nurses

- Nine (9) themes have emerged from the thematic analysis, namely: Be less stern, and I’d be more confident; More inputs please, and I’ll perform better; With less barriers, there’d be less drama; Talk to me so I’ll learn; Be considerate, I’ll be more focused with that; Your energy gets me motivated; Your competence is my key to success; You’re God-fearing, and so am I; and, Be fair, and I’ll be square.

4.5.1. Be Less Stern, and I’d be more Confident

- Developing confidence is an important component of clinical nursing practice. This entails that development of confidence should be facilitated by the process of nursing education so that students may become competent (Grundy, 1993) [29]. A lot of the participants have relayed that the characteristics such as being approachable, understanding, considerate and the like have a great impact on their performance at the clinical area. When asked about which characteristic of a CI he values most, C says: “A CI should be friendly. If a CI is friendly, the student will not feel nervous. In addition, the student would feel lax.” Meanwhile, F elaborates, “When a CI is approachable, I feel better. However, I do not appreciate the ‘approachable’ CI who would observe you yet will keep on correcting you, talking nonchalantly while doing so.” He further narrates that a CI’s physical presence would be more than enough; as long as the CI is there, he’d be more than confident of what he’s performing. Deviating, F mentions that if the CI is not approachable, it would seem like he could no longer do the procedure he is about to perform. Similarly, L reports that if she’s with a CI who’s not approachable, she’d feel frightened the entire shift. When she deliberates on whether or not to interact with the CI, she’d end up opting not to because it seems like the CI would somehow be mad at her. She reasons, “It seems like the CI keeps his eyes on you on whatever you do. As a result, you’d be scared. Instead of being able to perform the procedure calmly, you’d end up shaking once you see that he’s out there. It’s kind of like a sudden black-out.” In addition, participant 1 claims, “They always say that when you are in doubt, you should ask. But then, if you are scared of your instructor, you won’t ask anymore. A terror CI is a barrier for a student to become competent.” To add, D recounts an incident of his, “I believe I would have been able to perform properly when he was the CI. But then, he’s a CI who’s like constantly rattled and keeps on rushes things. Instead of me performing interventions carefully or gently, my hands would start shaking. And then you’ll see him behind you ready to pinch you in the event that you commit an error.”On a lighter note, B asserts, “If the CI is approachable, your performance in the ward would be better. Given that you are able to approach them, you’d be more confident that your actions are right. They are able to give inputs on what you may do.” This is in line with Johns’ [30] (2003) study where he stated that clinical supervision is recognized as a developmental opportunity to develop clinical leadership. Working with the practitioners through the milieu of clinical supervision is a powerful way of enabling them to realize desirable practice.Aside from gaining confidence when an instructor shows approachability, others view a CI’s jolliness as effective in boosting confidence. M, in particular, declares that when the CI gives off a jolly vibe, she’d lighten up and consequently end up performing her responsibilities better. She relays, “If the CI is jolly, you would not be anxious thinking that you would commit an error any time. Well, I’m like that. However, if the CI is jolly, you can easily do your thing; if ever you’d commit a mistake, you’ll know that he’d understand.”Exposing students to excellent role models inspires them to study better (Okoronkwo et al., 2013) [31]. Gillespie [13] (2002) similarly argues that the personality of a lecturer can have a strong effect on the behaviour and attitude of his students. It implies that clinical teachers should pay more attention to their characteristics if quality of their teaching is to be improved.

4.5.2. More Inputs Please, and I’ll Perform Better

- Participants claimed that to be able to perform interventions safely and appropriately, they need more of their clinical instructors’ guidance. As Viverais-Dresler & Kutschke [26] (2001) assert, the competent clinical teacher knows how to function in clinical practice and can guide students in developing clinical competencies. This requires the clinical instructor to be present with the student at the ward.Aligned to this, A quotes: “Because the CI is approachable, the student would not be afraid to seek consult with him.” B narrates an experience whereby it came to a point that the only thing checked by his CI during the entire 8-hour shift was his charting, and that’s it. He says, “My experience with him was… it felt like every time that I needed something, he would make ways to avoid me whenever I attempt to ask him about it. I tried several times to interact with him but to no avail.”Anchored on the above, K comments, “Of course, you as a student would want to confirm the steps of the procedure you are about to do for it to be more precise, even if you quite got the catch of how the procedure goes. At the least, he’d supervise you. Or he may add on to what you already know, simply by communicating it to you.” To boot, O points out that a CI should be approachable because in that way, students may easily communicate to them what they have observed in their patients. Also, she states, “The CI may help you in your patient’s plan of care. I have experienced a CI who wasn’t approachable. I don’t know if it was just me, but I really felt that he was not one who would entertain you nicely. As a result, I asked the opinions of my co-student nurses. Of course, you would not be that sure. What if they were also mistaken; thus, your efforts would go to waste.” Y had the same thought, whereby she claims, “You are students; all of you would not know things just like how a CI does.”On the same note, Lambert and Glacken [32] (2005) found that if students are to acquire knowledge of and skills in clinical practice, someone must be there to supervise and demonstrate how theoretical knowledge can be integrated into practice. Clinical supervision of students is a powerful way of enabling students to realize desirable practice.A better experience was related by B. He shares that once, there was a CI who helped him after he spoke about his problem. “‘Sir, how would I approach my patient? He doesn’t like me. He doesn’t trust me.’ So there, I asked my CI. He recommended trying explaining all interventions I perform, in detail.” B applied the CI’s suggestion and claimed it was effective. The patient finally nodded to what he strongly disagreed to initially. On the same note, N elaborates, “You can liberally ask your CI regarding your patient’s case so that you may deliver a more accurate health teaching to your patient. This is because primarily, you were able to approach your CI without hesitations.”In consonance, Elcigil and Sari [1] (2007) discovered that students wanted to work with knowledgeable and experienced mentors specialized in the given field. They stated that they learned more when the mentors presented knowledge, demonstrated new interventions and helped them perform these interventions.

4.5.3. With less Barriers, there’d be less Drama

- A few participants have offered some suggestions on how CIs may keep out from being the talk of the town. It may appear like they’re merely saying so to help the CIs out there, but they’re basically hitting two birds with a lone stone. They claim that these problems may be barriers in building a fine mentor-student relationship which may consequently hinder a good learning process; hence, the following propositions:For starters, Q explains, “It would be good if the CI and student maintain a professional mentor and student relationship. If they do not, somehow, the way you view the instructor would change. Even the way you treat the student attached to the CI’s name may also differ.” She continues, “Hence, when in the ward, you’ll just tend to be far from the CI, knowing that he behaves that way. Not really staying away; rather, it would be like limiting interactions or conversations with him.” As a result, there would be lesser chances of learning, because the contact between the student and instructor was voluntarily limited by the former. These particular findings are in agreement with Clifford [33] (1999), who emphasized that the teacher can be effective when maintaining a good interpersonal relationship with the students. Students argue that it is more agreeable if the CIs maintain a professional relationship with their students, elaborating that the instructors need not be too friendly just to show their openness. In the same way, Elcigil and Sari [1] (2008) documented that the student-teacher relationship truly is an important factor in the clinical learning environmentGillespie [13] (2002) elaborates that students learn if a connected relationship did not exist between them and their CI; yet as defined in this study, the group reiterated that the relationship should be focused on learning of skills and technical aspects that may help them realize the answers to their instructors’ queries.W shares an experience where she was scolded twice for committing a mistake – and this was a result of the CI somehow creating a wall to keep her off. “One time, in the delivery room, my CI was not that approachable. And then, a little while later while charting, I entered several minor mistakes. Once the staff nurse saw my chart, she got mad and called for me. I was scared, but I was okay, knowing that I’d solely take the blame. Suddenly, even the CI was sent for and also took some scolding which apparently was transferred again… to me. In the end, I kind of had a double beating, just because my CI was not approachable.” W further elaborates that being approachable is truly an ingredient a CI should not miss. According to her, she becomes more effective as a nurse if the CI is an open one because she is able to communicate everything to him/her. On the same ground, W explains that she is able to easily admit her mistakes and consequently wants to strive to learn more if the CI keeps the abovementioned trait. Meanwhile, D offers another option, “They need to level themselves with their students. They should not be serving as discouragement. As a consequence, when they keep on with such behaviours, unwanted talks about them would quickly sprout like grapevines everywhere. It would be like, ‘I dislike this CI, that also.’ ”On the same note, K adds, “It would really be best if the CI levels with his students. Sometimes, a CI’s negative actions and words become a barrier to maintaining a healthy mentor-student relationship.” When such a barrier exists, learning once again is impeded. He went on and continues, “They should level themselves with their students. Not too low, but in a way that they’d be able to healthily challenge their students. When faced with a Level IV, the CI should level himself with the thinking of someone who is in that academic level. They should never compare their students with themselves, being yet in a higher level. Obviously, they’d know better.”Murray and Main [34] (2005) asserted that the experience is the stimulus for learning and positive role models view reflection as an opportunity to advance their students’ nursing knowledge and clinical practice. For a CI to be effective during the learning process, he should display enthusiasm for the process, ask questions at a level appropriate to students’ abilities and stage of training and listen attentively to their responses.

4.5.4. Talk to me so I’ll Learn

- Several of the participants have related that it means so much to them that clinical instructors would interact with them more frequently for it allows them to gain more knowledge. As Y relates, “Personally, I want a CI who is approachable because when times come and you do not know a thing or two about something, you may approach the CI to obtain answers to your queries. You won’t be forever clueless about it, as a result. Also, a CI needs to be knowledgeable so that he’ll be able to give you the right answers.” Chow and Suen [35] (2001) reported that the students found the assisting role of the mentors as the most important factor and that mentors should create learning opportunities to facilitate learning in the clinical environment.Y further elaborates, “Of course, if the CI is not well-informed, you’d end up not knowing what to do either the moment that you ask him a question and no response will be given.” Participant 1 quotes, “An approachable instructor can mold a wise student, because the student gains more knowledge by asking.” As Murray and Main [34] (2005) claim, poor role modelling behaviours would see the mentor allowing no time for questioning and creating an atmosphere of possible fear, hesitancy and a lack of trust and respect.Meanwhile, E relates “When I was in 2nd year, at the OB ward, I deliberately searched for random information about this and that, just in case the CI asks me about them. When I was faced with the CI, she asked me about something; luckily, I knew what it was so I immediately responded. But then, the conversation ended just like that. As a student, you’ll always be looking for additional knowledge. As a result, I spontaneously disliked a rotation when she was the CI.” In comparison with a CI who teaches you impulsively about things not fully understood in the four corners of the classroom, E mentions that he would always keep on looking forward to the rotations in which he’ll be handled by that CI. Hayajneh [36] (2011) emphasized that the second most effective clinical teaching characteristic by nursing students was the ability of the CI to ask questions relevant to clinical practice. With this, the student’s critical thinking is enhanced; it also helps in retaining whatever is learned in the ward.Similarly, U points out that when a CI is knowledgeable, she gets inspired to perform interventions appropriately, ideally if possible. She adds, “It’s like you’ll be motivated to read every duty. When a CI is knowledgeable, he asks too many questions, and he’d be expecting to hear the right answers from you. There are others who seem to be so lax that you won’t be the least encouraged to read on this, to read on what is.”Having been exposed to the clinical setting for about a year and a half now, H believes that a clinical instructor should focus on teaching strategies. He states, “Honestly, my initial exposures in the clinical area had been stressful ones. It seemed like I was out of place. When we were already allowed to perform activities in the ward, I got into some thinking. ‘It’s like these had never been taught to us. We were not made aware of what we should be expecting prior,’ I thought.” Copeland [37] (1990) have elaborated that differences between actual and expected behaviour in the clinical placement creates conflicts in nursing students. Nursing students receive instructions which are different to what they have been taught in the classroom. As a result, anxiety has an effect on their performance. Nonetheless, H claims that the duties were memorable; he learned a lot of things which were not mentioned in the classroom. He adds, “Also, it is rousing when the instructor shares out-of-the-blue and fun facts ‘bout this and that, especially when he relates them to our patients’ cases. It becomes more effective when he teaches them in an engaging manner, which makes it more interesting and fun.”Deviating, U explains why wisdom is a requirement for a clinical instructor. She mentions, “An instructor should really be knowledgeable so that he’d be able to instruct or guide his students in any given situation.” Johnson-Farmer and Frenn [38] (2006) revealed that teaching excellence is a dynamic process involving the active engagement of students and faculty. The authors described active engagement as a process whereby the faculty is knowledgeable, uses multiple teaching strategies, clearly communicates expectations and outcomes, remains student-centered, and draws all students into active questioning and learning through discovery.On the other hand, M speaks out about CIs not being easy to talk to. She accounts, “There are instances when you believe that it’s better to ask help from the staff nurse instead of going to your CI, considering that it’s the CI’s job to look out for you, because he’s the CI. There was a time when I kept on bothering the staff nurse of my uncertainties because I was really scared to approach my own CI.”

4.5.5. Be Considerate, I’ll be more Focused with that

- Most of the participants have declared that they are able to function better when their CIs are considerate and understanding. Despite the fact that the participants are already in the 4th level, all of them appeal that they still need their CI’s guidance. Wolf et al. [39] (2004) identified faculty traits which serve as strengths; to wit, being knowledgeable, strategic teaching with professionalism, being supportive, and creating positive learning environment with display. These findings coincide with the following findings of the present study.For instance, R reiterates, “A CI should primarily be understanding. Of course he knows your level, what you can accomplish at that level. Hence, he should not be expecting more of what you can do. It does not mean that because you are already a senior, you’d already know everything. There are also times when you will need his supervision.” Moreover, the participants have related that CIs should refrain from getting their blood pressure pumped up, in a sense that they should avoid getting angry at mistakes their students commit. L says, “A CI should never scold you in front of your patient. And if ever you commit an error, he should at least approach you in a nice way. He should not easily get angry, flashing irritated stares at you; if a CI does that, of course you’ll feel bad.” This is in agreement with the finding of the Ali [21] in 2012 which strongly indicated that nursing students perceive that clinical instructors should demonstrate caring behaviours to facilitate reduction of their anxiety in the clinical setting.Meanwhile, O gives a detailed explanation on why she believes that a CI should have patience. She claims, “There are times, especially in charting, when CIs assume that the moment their students saw their patients, after they get their clients’ vital signs, they would immediately have a focus running in their minds. Actually, that’s not even possible. Also, in the OR, especially when you’re arranging instruments in your tray, and you know that your CI is close and is ready to pinch you, you’ll get more tensed. Is it not possible that the CI would just let you be? Can’t he just let you prepare what is needed on your own, considering that the patient has not yet arrived, or the patient is still being anesthetized?” Furthermore, she says that she can’t concentrate; she gets tensed when the CI keeps that behaviour. In the event, the more she could not focus herself on what she’s performing. When the CI nudges her, exclaiming, “Faster! Get that ready…,” the more she gets tensed. Instead of focusing on the proper procedure, she ends up thinking of her speed, because it is what the CI wants her to focus on. Instead of being right on the track, she becomes nuts especially when the CI pinches her, crying out, “Hurry! Pass that instrument.” How could a student nurse function in such a situation? As T says, “Fear is not conducive for learning.”Moscaritolo [23] (2009) revealed the same findings he concluded that clinical instructors should understand how their behaviour influences the anxiety levels of student nurses and their performance of skills in addition to learning in the clinical setting. He further elaborated that high levels of anxiety lead to interference with learning, and the ability of student nurses to perform safely and effectively with patients.R narrates a dreadful experience that has left an awful mark on her. “CI B terribly scolded me.” “It was like, ‘Wait, this is the first time I’m performing the procedure,’ I thought. When he scolded me, it was like I did very terrible thing. I thought of giving up, of not continuing the return demonstration. And up to this moment, when I perform the procedure (suctioning), there’s still that bit of panic in me. I still remember how that CI got mad at me like crazy back then.” When asked what she believes the CI should have done back there, she suggests, “He should not have gone mad so quickly. He should have taught me how it should really be done; he should have corrected on what I did wrong. Not… I believe he said something that really hurt me, I just don’t remember what it was. Hence, nowadays, when I perform the procedure, I don’t want to be alone. I really need someone to accompany me.”The above experience would denote that clinical instructors should be trained to utilize appropriate teaching strategies to be able to properly guide their students in the most humane way possible. This is supported by the findings of Nelson [40] (2011) and Hayajneh [36] (2011), whereby their participants thought that the ideal clinical instructor should be informative, able to give valuable advice, supportive and encouraging. These, with the ability to answer questions appropriately, if possessed by the CI described above, would have been beneficial to the participant. Having to suffer humiliation would have been prevented if only the CI practiced the characteristics being emphasized. Meanwhile, S believes that a clinical instructor should have consideration and acceptance of the students’ limitations or shortcomings. She claims that such traits greatly affect the student nurses’ performance in the clinical area. “If they give off an attitude, for instance, saying, “What are you doing? Why is it like this,” you’d lose your confidence, you’d lose everything. Even though they have the brains, even if they are the most intelligent, that wisdom they have would all go to waste if they do not take students as students – that apparently, their students are still learning.”Brookfield [41] (2006) accounts, some level of anxiety is needed to support learning drive and critical thinking. However, excessive anxiety or stress in the clinical setting created by a clinical instructor may do the opposite and negatively influence nursing students abilities to focus, recall and problem solve (Moscaritolo, 2009) [23] which is in agreement with the above findings.P pitches in, saying, “When the CI is a person who easily gets mad, you get affected. Despite the fact that you want to have fun in your shift, his vibe would make you lose your lively mood to continue on with your duty. Your performance would get affected; your drive would be gone, and in the end, your patient gets the bad side. It’s like your patient would be left out because you’re no longer in the mood.” Al-Hamdan et al. [10] (2014) support these statements as they have concluded that a mentor has a major influence on students’ drive to learn and their capacity to adjust to new conditions. Mentors’ activities and qualities play a vital role in the clinical teaching and students’ education.F also mentions something on being close-minded. He elaborates, “There are those ones who are close-minded; they’re the types who impose that what they know is what’s right. Ideas would only matter to them if it is what they know. When the CI is close-minded, personally, I get frustrated and my performance goes downtown.” Aligned with this, Al-Hamdan et al. [10] (2014) mentioned in their literature that mutual respect between mentor and mentee is considered important for success, coupled with the need for mentors to be non-judgmental and open-minded.McGregor [42] (2007) explained that a toxic student-instructor environment can lead to the following: (a) loss of a worthy student to the nursing profession, (b) avoidance of the clinical instructor and therefore loss of learning opportunities, (c) inability of students to be their authentic self, and (d) the development of underlying frustration and anger suppressed for fear of retaliation.Conversely, the participants reveal that if the clinical instructor is patient and considerate, they get more confident. S mentions, “Because CI C was accepting, I knew that my performance has improved. I was not afraid to take on the proper assessment procedures.” She shares quite a detailed story of her experience back during her sophomore year as a comparison. “When I was in second year, CI D... because of her intimidating character, I felt so stupid during that one shift. It seemed like all that I’ve learned vanished all of a sudden. All I thought was, ‘Gosh!’ I knew I could have handled her questions – that I would have been able to give the correct answers at other circumstances but not that one time, because of the attitude CI D was presenting. She was pressuring me, instead of giving me ample time to formulate my response.”Moreover, O declares that when the CI is patient, the student nurse would be able to gain his focus. The student nurse will be encouraged to perform better and quicker as possible. P adds, “When the CI is patient, the duty would be fine. Not that you become so assured, but you know that you’ll be able to perform all interventions that you plan to do; that you’ll be able to finish everything in time without making haste.”Nonetheless, some student nurses still believe that a bit of strictness in a CI would somehow benefit them. G mentions that he gains more knowledge when the CI is quite stern. He claims, “He’ll correct you when you’ve committed a mistake.” On the other note, he elaborates, “However, if the CI is too strict, it won’t do me any good. It would be more difficult for me, thinking that anytime, he’ll be scolding you once you perform something incorrectly. Nonetheless, if I’ll ever be scolded out of the CI’s sternness, proper strictness at that, I’ll take it as a challenge. Somehow, I’ll strive to do better. However, if a CI is very lax, has no sense of austerity at all, he may not be able to give you sufficient corrections whenever you commit a mistake at the area.”Similarly, D expresses that he sees the un-approachableness of a CI as challenging. He confides, “When the CI is not approachable, it would somehow get you to be stricter with yourself, in whatever you perform. You’ll be stern with your own self in a sense that you’re being challenged by the way the CI is being somewhat rigid. You’d be motivated to perform with all your best because naturally, you’re scared by how the CI behaves. When the CI levels with you, it would be like, nothing. You’d start treating him like a friend; in return, it would appear like everything that you suggest would easily be green lighted.” G adds, “If the CI lacks strictness, you won’t be disciplined. If you have no discipline, your performance would be affected. Tendency is, you’ll have difficulty building good relationship with others – co-workers, CIs and your patient.” These perspectives may be explained by Bandura [43] (1977) where he stated that people with a high sense of self-efficacy view “difficult tasks as challenges to be mastered” as opposed to people with low sense of self-efficacy who tend to avoid challenging tasks. Furthermore, he said that as one’s sense of self-efficacy increases, so too does how long they will strive and how long they will persist in their attempts. It was noted that both participants who have mentioned that a CI’s strictness are considered as a challenge are males. Few literatures can be found regarding differences in self-efficacy when sex is considered. In the field of engineering, a male-dominant course, research suggests that decreased self-esteem and self-efficacy of women in engineering majors are significant obstacles to persistence (Somers, 1986) [44]. This is in alignment with the present study in which males were noted to display a more challenge-taking behaviour which may be assumed to be a result of their self-efficacy.Meanwhile, participant I extends a somewhat different view regarding the matter. “Considering that we are already in our 4th year, I believe it would be better if they become more approachable, more encouraging, at this point in our studies,” she relays. “Of course, if they have been that level of ‘encouraging’ to Level III students, it would be helpful. For me though, if they have behaved as such while we were still in Level III, we may tend get careless. Hence, I believe that the CI should not be very encouraging more so to the students in Level II. When a student is still in that level and the CI is very gracious, tendency is they get to a different level of close and the student may consequently take the CI for granted.” She mentions her views ‘as-a-matter-of-factly’ which showed that it was really a stand that she had always been taking on.Digressing, K focuses more on trust issues. She narrates, “Somehow, a student becomes more confident in whatever procedure she’ll be performing when he knows that the CI trusts him. The effect is completely the opposite when a CI shows doubts on the student nurse’s abilities.” She elaborates that the CI’s behaviour, the way he would show his doubt, would definitely lower the student’s self-esteem. When asked about what behaviour she is pertaining to, she replies, “You’ll immediately catch that the CI has doubts on you when he starts blabbering nonsense at you, instead of properly asking how you’ll be performing the procedure.”The above behaviour shown defies the propositions of Jarvis and Gibson [45] (1997) which state that a relationship of trust and respect is essential if there is to be ‘an enriching teaching and learning transaction’. The mentor must create trust in an atmosphere where the student can ask questions freely without feeling foolish (Ellis and Hartley, 2000) [46].

4.5.6. Your Energy Gets Me Motivated

- When asked what characteristic an instructor should have, a lot have agreed on the behaviour being energetic. B explains, “If the CI is energetic, he’d be able to move his students; the energy that he emanates can be contagious. In addition, he’d also have the ability to motivate his students if he’s energetic.” Wolf et al. [39] (2004) related that this ability encompasses the skills required to transmit knowledge, skills, and attitudes from the teacher to the student. Aside from these, they have also pointed that this ability requires being able to create an atmosphere that encourages student learning.H forwards his appreciation to the CIs who have vibrant energy and positivity. He says, “When they know that it’s your first time pulling off that skill, they’d be there guiding you. Their simple words of “You can do that” expressed with sincerity topped with a simple smile can get you moving a long way.”In like manner, Hayajneh [36] (2011) stated that the ideal clinical instructor is a dynamic, energetic person who stimulates students’ interest in patient care, and helps students’ ability to relate therapeutically to patients; passionate about her work and presenting a caring, empathetic approach. Cook [47] (2005) similarly shared that student anxiety was lower when inviting teaching behaviours were utilized by clinical instructors.

4.5.7. Your Competence is My Key to Success

- Competence was valued by most of the participants. Participant I relates, “For me, for a clinical instructor to be effective, he or she must display constancy in everything. Meaning, he or she must be competent in the area for the student nurse to follow him. He must serve as a role model.” Berggren and Severinsson [48] (2003) suggested that the clinical nurse supervisors should express their existence as a role model for the supervisees. Participant I adds, “Still, the most important characteristic is professional competence. How can they be effective if they themselves do not know what they’re teaching? On another note, the CI’s competence ensures security of the students; the students get guaranteed knowing that the CI could readily help them.” She continues that a student may also get inspired when the CI is competent. Seeing their CI’s level, students get motivated to perform their best, she asserts.Ali [21] (2012) discovered that nursing students wanted their clinical instructors to be knowledgeable and competent in their own field and agree that knowledge and competence are the most important and essential components for effective teaching. He asserted that these may be because respondents wanted to spend their clinical training with specialized educators and more experienced instructors, allowing them to feel more secure in the clinical environment.Meanwhile, K gives a more specific clinical teaching behaviour that a CI should have. “For me, a CI becomes more effective when the CI conducts pre-conferences. There is this one CI who never fails to conduct pre-conferences whenever he is our CI. In effect, I really never got lost in the ward, literally and metaphorically.” She elaborates, “In contrast, when a CI does not perform a pre-conference, you’d tend to commit mistakes. The even heavier downside is that you’d get blamed for it; you’ll be told to write LEs and such.” “There really is this one CI whom I have appreciated because he orients his students as every rotation commences. He shows where things should be kept, taken, and so forth. Also, he is a CI who does not get agitated easily. He’ll point out your mistakes in a gentle manner which gets you encouraged to perform better,” she narrates.Edwards et al. [49] (2004) stated that it is important that clinical teachers plan the orientation to the facility (placement), which includes providing information about the location and physical setup, the agency policy, daily schedules and routines, procedures for responding to emergencies, and documentation of patients’ care. Moreover, Ali [21] (2012) declared that a clinical instructor should be able to communicate expectations to students in a clear way, be well prepared, check student understanding, ensure that basic familiarization is well organized, and demonstrate that the ward can be regarded as a good learning environment.Meanwhile, participant I narrates, “Another characteristic that a CI should possess is the ability to pose his authority. For example, the student sees him as an instructor. Personally, I believe that you’d easily respect a person who has both authority and skill. Naturally, a person respects a person with authority; but the respect and honour is greater when the person in authority also exhibits sufficient skills. In the area, the student would view him more as a clinical instructor. Consequently, learning would be more effective because he has the competence which goes hand in hand with knowledge.”

4.5.8. You’re God-fearing, and so am I

- Anchored on the discourse, G blurts out that the prized characteristic that a CI should possess is fear of God. He confides, “First, the CI should be God-fearing; in that way, I’d know that the CI has a good personality. Whatever mistake I lay upon myself, I know that we’d still be in good terms considering that the CI is God-fearing. And even when we’ll be at our worst point in the mentor-student relationship scale, there would always be that one similarity that would bring us together, and that would be our value for the Lord.”

4.5.9. Be Fair, and I’ll be Square

- A details the necessity for a CI to be fair. He accounts, “A CI should be fair so that he may inspire the students to go for the trophy. If a CI is not, a student would opt not to give the best shot at everything because he only sees the one he likes.” “When the CI is not just, I tend not to ask him; I only approach him when I have to get my chart checked, and that’s it. It would appear like I only need him to sign my chart, and I’m done. Also, when he’s not fair, you’d rather not show what’s in store because he’ll give you a grade that’s just the same as when you opted to go the other way,” he concludes.Thomas [50] (2003) identified the presence of anger in nursing students related to critical and unfair nursing clinical faculty. Emotional responses to unfair treatment by nursing faculty led to negative consequences, summarized as: (a) interference with learning, (b) decreased role development, (c) dissatisfaction, and for some students (d) leaving the nursing program or nursing completely.Understanding that responses may command evaluation, Murray and Maine [34] (2005) found that student nurses are discontented by ineffective mentors when they provide destructive feedback or fail to provide any feedback on performance.

4.5.10. Summary of Findings

- Developing confidence is an important component of the clinical nursing practice. Students believe that the characteristics such as being approachable, understanding, considerate and the like have a great impact in their performance at the clinical area, making them better and more confident. The opposite of these traits, on the other hand, pose anxiety on the students, making them frightened and less efficient as nurses. Given that the members are able to their CIs, they get more confident that their actions are right, consequently making them more competent student nurses. To be able to perform interventions safely and appropriately, students claim that from time to time, no matter what level they’re at, their clinical instructors’ guidance would always be a necessity. As a student, they would want to confirm the steps of the procedure they are about to do for it to be more precise. A CI’s openness is beneficial to them even to the simple intervention of delivering accurate health teachings. Accordingly, this is due to the fact that they can liberally confirm their thoughts regarding the matter.Moreover, students have argued that it is more agreeable if the CIs maintain a professional relationship with their students, elaborating that the instructors need not be too friendly just to show their openness; they reiterated that the relationship should be focused on learning of skills and technical aspects that may help the students realize the answers to their instructors’ queries. A CI’s openness also helps student develop maturity by allowing them to easily admit their mistakes.Students further accounted on the CIs’ need to evaluate how they treat their students. Accordingly, the CIs should learn how to level themselves with their students for the following reasons: reduction of anxiety and pressure among their students, prevention of discouragement for further learning, and upholding of a good mentor-student relationship. Despite a lot of students disdaining CIs who are not approachable, still, there are a few who view this as a reasonable challenge. On interaction, the group related that the act means so understanding that it allows for the verification of knowledge; thus its supposed frequency. They elaborated that a CI needs to be knowledgeable so that he’ll be able to give students the right answers in any given situation. Furthermore, students declare that they get motivated to learn more and strive to perform better in such event. As claimed, being able to function better is reinforced by a CI who shows consideration, acceptance and trust in his students. Accordingly, a CI should not be expecting more of what the student can do. Aligned to this, the participants have shared that CIs should know how to handle stress and manage their anger issues. This is to facilitate reduction of anxiety in the clinical setting. When a CI transfers his stress on the student by way of getting mad at the latter, the student tends to lose his focus and consequently unknowingly commits mistakes. In the end, the student’s patient gets the bad side.Students also value a CI who is energetic. They say that it is contagious, getting them moved and driven to perform better as nurses. Besides that, a CI’s simple words of “You can do that” expressed with sincerity topped with a simple smile are believed to keep a student moving uphill.Distinctly, ‘competence’ was prized by student nurses. With competence comes constancy, role modelling, and orientation skills. These are ingredients claimed by the group to be beneficial in the learning process. These particular traits help CIs bridge the gap between theory and practice. Meanwhile, a participant has emphasized the need for a CI to be God-fearing. Accordingly, it brings him closer to the CI, knowing that the CI also values the Lord the way he does. Finally, a CI should be fair in all manners of evaluation to motivate the students to bring out the best in them. If a CI does not, a student would opt not to give the best shot at everything because he only has eyes for the one he likes.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- The results of the study revealed that sex is not a variable in student nurses’ perceptions of effective clinical instructor characteristics. Conversely, it was established that difference in academic level poses an effect in students’ perceptions of the identified characteristics. Significant differences can be seen when Levels I, II, and III were compared to Level IV in their perceptions of professional competence, teaching strategies and personal attributes. On the importance of the subset ‘relationship with students’, all lower levels differed significantly with the seniors, except for the freshmen. For the ‘evaluation procedures’, only Levels III and IV statistically differed from the other. Moreover, the top ten (10) effective clinical instructor characteristics were identified as follows, in descending order: ‘Respects student as an individual’, ‘Shows clinical skill competence’, ‘Demonstrates competencies that are to be emulated by students (Role modeling)’, ‘Communicates knowledge for safe practice’, ‘Evaluates students objectively and fairly’, ‘Encourages students to feel free to ask questions on evaluation result’, ‘Provides students with opportunities to practice learning skills, ‘Demonstrates flexibility in clinical settings’, ‘Responds promptly and confidently’, and ‘Offers opportunity to practice before evaluation’. The student nurses considered professional competence as the most important subset among the five (5) identified effective clinical instructor characteristic categories.From the results, it is deduced that sex is not a variable in the student nurses’ perceptions of the effective clinical instructor characteristics. Furthermore, it is concluded that difference in academic level poses an effect in students’ perceptions of the identified characteristics. Nonetheless, the researchers believe that further studies need to be conducted to validate them, with a wider population, and possibly, the inclusion of the clinical instructors’ views themselves. Also, refinement of the instrument by combining similar items, factor analysis, and renaming categories would aid in providing a more user friendly and discriminating tool is to be employed when replication of the study is intended.Professional competence is deemed to be the most important characteristic among the five (5) domains. It was supported by the inclusion of three (3) competence-related clinical teaching behaviors in the upper half of roster. By and large, characteristics pointed out by the students during the interviews are clinical teaching behaviors that help them bridge the gap between theory and practice. Personal attributes have topped the interviews, with students reiterating that these are more important than competence. In view of that, they claim that a student would less likely benefit from a CI’s excellence and competence if he is not approachable, a personality trait mentioned over and again during the interview sessions. Nonetheless, collated quantitative and qualitative findings imply that generally, CIs need both character and competence when aimed at gearing student nurses to become successful members of the profession. Clinically, the results may be utilized to improve faculty awareness of students’ views on their performance in the area. Hence, it is recommended that the institution establish programs for clinical instructors to develop in themselves more clinical teaching behaviors that could facilitate their methods of bridging theory and practice gaps. It may also help if clinical instructors be provided with opportunities to examine clinical issues with co-faculty members to set courses of action that may promote healthier learning in the clinical area. In general, to achieve excellence in nursing education, it is imperative that extensive orientation and re-orientation of principles and evidence based practices of clinical teaching behaviors be practiced.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- The authors extend their deepest gratitude to the experts who have validated the tool, Prof. Doris S. Natividad, Ms. Maureen E. Gay-as, Ms. Editha A. Grande, Ms. Angeli T. Austria, Mr. Glenn Ryan I. Palao-ay, and Mr. Keverne Jhay P. Colas. They also forward their utmost appreciation to all students who willingly participated in the study; without their wholehearted input, this study could not have been possible. No manuscript is ever a reality without the dedication and perseverance of editorial staff who were our colleagues. This was a non-funded study and there is no conflict of interest.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML