-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2014; 4(3): 33-36

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20140403.01

Florence Nightingale who Raised Nursing as a Highly Profession

Mohammad Taghi Sarmadi

Tehran, Iran

Correspondence to: Mohammad Taghi Sarmadi, Tehran, Iran.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

For centuries, religious orders had followed their vows of charity by looking after the ill, and infirm and providing them with food, drink, beds, bedding, and clothes. The modern term “sister” derives from the sister of the convent. Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), an English gentlewoman whose dedication and service during the Crimean War (1853-1856), led to a dramatic reduction in mortality rate. She was known as “The Lady with Lamp” after her regular habit of making rounds at night. She organized a fund to establish a training institute for nurses at St Thomas’ Hospital in London (now part of King’s College London), and improved hygiene conditions and the establishment of an army medical corps. Her book, “Notes on Nursing” (1859) was the profession’s best seller.

Keywords: Florence Nightingale, Crimean War, Conventional nursing, Modern secular nursing

Cite this paper: Mohammad Taghi Sarmadi, Florence Nightingale who Raised Nursing as a Highly Profession, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 4 No. 3, 2014, pp. 33-36. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20140403.01.

Article Outline

1. The Crimean War

- The Crimean War (1853-1856), was fought between Russia on one side and Turkey, France, Britain, and Sardinia on the other side. Although militarily insignificant, it was politically important. The war rose from a dispute over protection of the holy places in Palestine, then under Ottoman Turkish rule. By weakening Russia and by making the Italian question one of general European concern, it furthered the success of national movements in Italy, Germany, and the Balkans, and led to the reorganization of the European state system. The Turks declared war against Russia in October 1853. Britain and France feared Russian domination of the route from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, and so choose to help Turkey. When a Turkish fleet was destroyed by Russia, French and British fleets sailed into the Black Sea; their armies went to Crimea in September 1854 and laid siege to Sebastopol for a year. In autumn 1855 and early in 1956, Russia accepted peace terms. Most to the losses on both sides resulted from hunger, exposure and disease during the siege. Russia blindly stumbled, to destroy the myth of Russian military might and to set free in Central Europe the forces of liberal nationalism [1].

2. Nightingale’s Own Campaign

- The Crimean War, Was the first war to take place in the era of steamships and telegraph. “The Time” newspaper despatched a correspondent to cover the war, and he sent back a graphic description of Scutari Military Hospital, which was overcrowded, had blocked sewers, no blankets, no bandages and no trained nurses. Sydney Herbert, a cabinet minister who was a friend of Nightingales, asked Florence to go to Scutari and recognize it, which she did.Florence took contingent of Catholic, Anglican, secular and trained nurses with her to the Scutari Military Hospital to care for the British wounded in the Crimean War. She found conditions in the overcrowded military hospitals appalling: miles of dirty beds, no facilities or equipment with which to care for or properly feed the soldiers and a mortality rate which at times reached over 40 per cent [2].She not only offered aid and comfort, but restructured many military hospital services, waging her own war on disorganization and dirt. Together with others, her efforts paid off handsomely. When Nightingale’s party first arrived at the Scutari base camp in November 1854, the soldiers there were suffering a 60 per cent death rate. But at the end of the period of her reorganization of the hospitals there and at Balaclava, the mortality rate dropped just to over one per cent, with an overall drop in British military hospitals from 42 per cent to 2.2 per cent. While many factors contributed to this drop, the cleaning and scrubbing she organized undoubtedly helped. From her time at least, the cleansing and whitewashing of up-to-date hospital interiors left its own chemical scent on the staff and inmates [3]. Although most of her hours were spent in organizing, directing, and writing, the soldier quickly responded to her obvious concern for their welfare: “we lay there by the hundreds; but we could kiss her shadow as it fell and lay our heads on the pillow again content [4]”.

| Figure 1. Florence Nightingale founded the modern secular school of nursing |

3. More about Florence Nightingale

- Florence Nightingale (12 May, 1820-1910), British pioneer of nursing and hospital reforming, born in Florence while her wealthy parents were visiting Italy. She reacted strongly against the pleasure-loving society that admired her girlish charm and wit. In 1837, she developed a strong sense of vocation. She decided to devote her life to nursing, then a despised and undisciplined occupation carried on by ignorant and often delinquent nurses in filty, fever-ridden hospitals [10]. Many of them were lazy, unkind, unhygienic, drunken, and often stole from their charges. They earned nursing a very bad reputation. Florence’s parents opposed her plans, but she persisted. When she was 24, began her campaign in 1844. She had already refused to marry some very eligible suitors. It took her seven years to convince her parents of her intentions.

| Figure 3. A pair of moccasins which Nightingales wore in Crimean War |

4. Conclusions and Impact

- Some 2000 years ago, wounded Roman soldiers were cared for by auxiliary soldiers and slaves. With the spread of Christianity, monks and nuns cared for the sick. Most nursing took place at home and was haphazard. In the 18th and 19th centuries public hospital were established, but even then the nurses were mostly untrained, and ill-paid women. Catholic and Protestant groups began to train nurses. In 1836, a priest Theodor Fliender (1800-1864), and his wife founded a three-year training course for nurse-deaconesses in Germany. English Quaker and prison reformer, Elizabeth Fry (1780-1845), visited them and, back in England, helped found the Institute of Nursing, which improved the standards [14] of “caring for the sick.” But it was Florence Nightingale, the most outstanding figure in the history of nursing who dedicated her life to nursing at a time when it was shunned by other English gentlewomen of her class. She also travelled all over the world, taking her ideas about nursing with her, to found nursing schools and to change the image of nurses worldwide. Miss Nightingale’s brilliant success raised the social standing of nursing as a profession and stimulated movements for the teaching and training the nurses in Great Britain and throughout the world. The opening of her nursing school in London, marked the beginning of the transition of nursing from an art practical by dedicated but untrained workers to a profession whose members are trained in the basic medical sciences and are capable of administering the complex procedures of modern medicine [15].

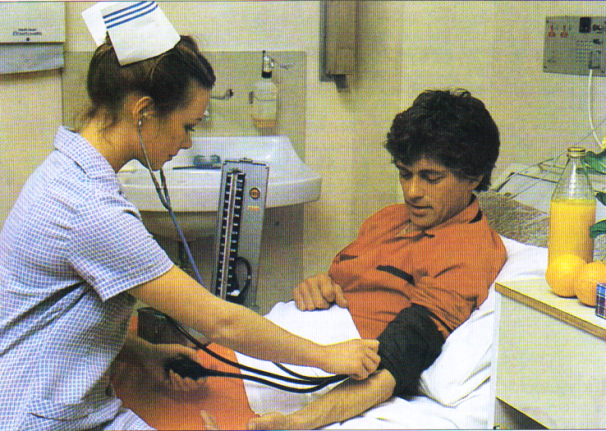

| Figure 4. Nightingale revolutionized standards of cleanliness and patient care. Today the nurses play an important role in the curing of the patients |

| Figure 5. Nightingale’s statue, in London Road, Derby |

| Figure 6. The plaque for Florence Nightingale, South Street, Mayfair |

Note

- ∗ She took 14 trained nurses and 24 nuns with her because there were more suitably trained nuns than there were nurses.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML