-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2014; 4(2): 26-31

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20140402.03

Psychiatric Workers’ Perception of Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill in Government Hospitals in Jamaica

Andrea Pusey-Murray, Hermi Hewitt, Karen Jones

Caribbean School of Nursing, University of Technology, Kingston, Jamaica

Correspondence to: Andrea Pusey-Murray, Caribbean School of Nursing, University of Technology, Kingston, Jamaica.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2014 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

The purpose of the study was to investigate the perceptions that psychiatric workers in Government Hospitals in Jamaica have concerning deinstitutionalized patient care for the mentally ill. A qualitative descriptive design was used. Participants were selected through convenience sampling and comprised twenty-two psychiatric workers who at the time were working with psychiatric patients in two public hospitals. Ethical approval was obtained. Data were collected through three focus group discussions guided by five broad questions. These sessions were audio taped with the consent of participants. These data were then transcribed, analyzed for themes and relevant responses subsumed under each theme. A four-item questionnaire was also used to capture the demographic data of participants. The results showed that participants’ perceptions of deinstitutionalization were both positive and negative. The main themes that emerged were: family bonding; stigma and discrimination; community reaction/unpreparedness; regression of patients; inadequate community resources; absence and noncompliant with medication; caregivers coping mechanism; benefits of institutionalized care and mental health officers’ roles.

Keywords: Community mental health services, Community resources, Deinstitutionalization, Institutionalization, Stigma and discrimination

Cite this paper: Andrea Pusey-Murray, Hermi Hewitt, Karen Jones, Psychiatric Workers’ Perception of Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill in Government Hospitals in Jamaica, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 4 No. 2, 2014, pp. 26-31. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20140402.03.

1. Introduction

- Deinstitutionalization is the removal of patients’ care from hospital to community, usually within proximity to their residence. Patients with long term chronic mental illnesses can have an improved quality of life by remaining clinically stable with less medication when supported by a mental health system with adequate community resources and continuity of care (Hobbs, Newton, Tennant, Rosen, & Tribe 2002). The deinstitutionalization process enables the reduction of beds in the existing psychiatric hospitals rather than a structural change with a modification to psychiatric departments in general hospitals (Haug & Rössler 1999). Deinstitutionalization in Jamaica began in the 1960s and overtime the number of hospitalized patients has decreased. In 1960 there were 3,094 psychiatric patients in the island’s only mental health Hospital and currently there are approximately 900 hospitalized patients (Hickling, & Gibson 2005). Most (60%) of the hospitalized patients are over the age of 65 years (Hickling, & Gibson 2005; Abel, McCallum, Hickling & Gibson 2005). It is purported that there are three component processes in deinstitutionalization (Bachrach, 1976). The processes are the release of persons residing in psychiatric hospitals to alternative facilities in the community; the diversion of potential new admissions to alternative facilities; and the development of specific services for the care of a non institutionalized mentally ill population (Bachrach 1976). In Jamaica it has been demonstrated that deinstitutionalization provides individualized care for mentally ill patients for a diverse and heterogeneous group of people. However for deinstitutionalization to work successfully, service planning must be tailored to the needs of individuals (Sartorius, 1992).Lamb & Bachrach (2001) made the point that deinstitutionalization provides the opportunity for acutely ill patients to have shorter hospitalization. The author further suggested, however, that the discharge from hospital should not take precedence over clinical concerns. Heginbotham (1998) describes deinstitutionalization as a double edged sword by indicating that on one hand the patient is being released from the confinement of mental hospitals and reintegrated into society. Conversely, deinstitutionalization brings into sharp focus the behaviors of mentally ill persons that in the first instance caused them to be shut away from the society at large. The mentally ill patients without support systems may have difficulties coping when they are discharged from the hospitals to their communities. According to Bachrach (1996) Canada and the USA have many patients who have benefited tremendously from deinstitutionalization. There is an indication that patients are living happier and more hopeful lives than they otherwise would have in hospital-oriented settings (Bachrach 1996). Pusey-Murray and Miller (2013) found that the caregivers recognized the importance of and valued social interaction with family members and the community, both for themselves and their sick relative. People living with mental health problems and illnesses often report that they experience of stigma. These experiences are usually from members of the public, friends, family, co-workers, and even at times from the service systems that they turn to for help. It is believed that these experiences are more devastating impact on them than the illness itself (Canadian Alliance on Mental Illness and Mental Health 2007). Sealy and Whitehead (2006) indicated that the policies of deinstitutionalization provide savings by reducing mental hospital beds. The author further stated that these savings can be invested to improve mental health services. These services would treat patients in their communities and allow them to stay at home rather than becoming institutionalized. Sealy and colleague described three primary bases for deinstitutionalization policy: Firstly, psychiatric hospitals are expensive and provide for fewer patients than can be served in a community based setting. Secondly, people are more likely to access services that are located close to where they live; and thirdly, reducing admissions and length of stay in long-term psychiatric hospitals allow patients to make maximum use of their current social supports and or reduce their level of readjustment upon discharge (Sealy & Whitehead 2006).Deinstitutionalization started in Jamaica over five decades ago but up to this time the process has not been fully completed. Mental Health Officers were introduced into the system to facilitate deinstitutionalization, but there has never been enough to meet the needs. Studies have been conducted to determine the Jamaica population’s receptiveness to the rehabilitation of persons diagnosed with mental illness back into society (Hickling & Gibson 2012; Abel, McCallum, Hickling & Gibson, 2005). The authors found that there are both positive and opposing views regarding rehabilitation of mentally ill patients in Jamaica. There are two government hospitals in Jamaica that provide exclusive care for the mentally ill. One is the Bellevue psychiatric hospital in the urban setting. The other is a floor at the Cornwall Regional Hospital in a rural setting. Recently the Ministry of Health, Jamaica has accelerated its effort to deinstitutionalize mental health care. This is being done by making mental health services more available within the community, supporting training of mental health/ psychiatric nurse practitioners and the development of limited residential services for discharged patients. Psychiatric health workers have been caring for patients with mental illnesses in the two government hospitals for 153 years and 38 years respectively. Therefore, their input is vital in the decision-making process of deinstitutionalization.The aim of the study was to explore the perceptions that psychiatric workers held regarding deinstitutionalization of mentally ill patients. The objectives were to identify the differences in the perceptions held by psychiatric workers regarding hospitalized care of the mentally ill and deinstitutionalized care; and to identify the views of the psychiatric workers about care of the mentally ill patients in the community.

2. Methodology

- Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committees of the University of Technology, Jamaica, the Western Regional Health Authority and the South East Regional Health as well as the Authority Advisory Panel on Ethics and Medico-Legal Affairs in the Ministry of Health.Participants were selected by convenience sampling obtained through published recruitment and face-to-face invitation. Data were collected through focus group discussions involving 22 participants. The participants comprised psychiatric health workers who were actively caring for psychiatric patients in two Government Hospitals. Five broad questions guided the focus group discussion namely: 1. What do understand by the term deinstitutionalization?2. Based on your understanding of deinstitutionalization, how effective will deinstitutionalized care be as opposed to institutionalized care?3. As a member of the health care team, do you have any concerns about deinstitutionalization?4. Are there any positives that the patients have been experiencing with institutionalization?5. Do you think the community is equipped to accept the return of the mentally ill patients to the community and homes?Sessions were audiotaped with the consent of participants. Data were then transcribed, read independently, themes identified and relevant responses subsumed under each theme. A four-item questionnaire captured the demographic data of participants. The questions were: what is your gender? What age category do you best fit in? What is your present employment status? What is the name of your Institution?How long have you been employed to this institution? Please state in years.

3. Results

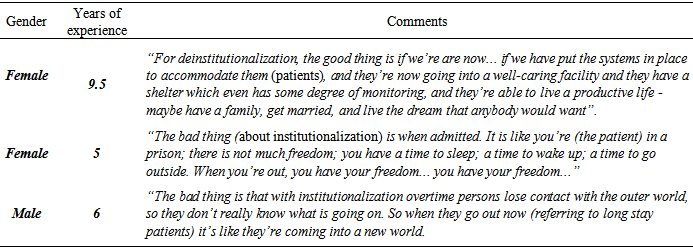

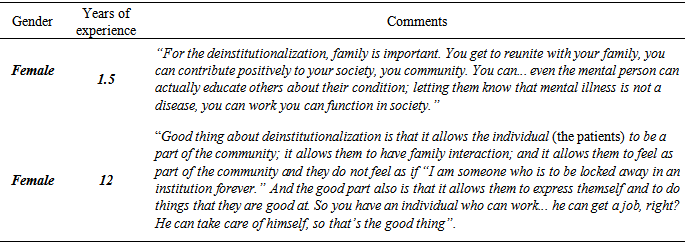

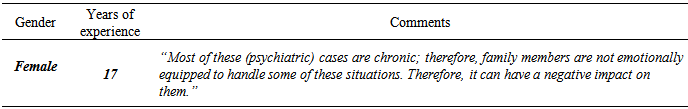

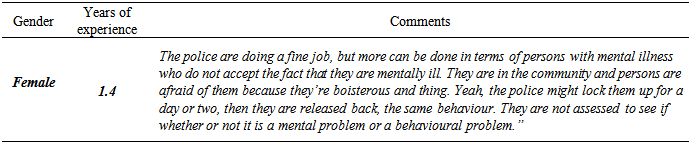

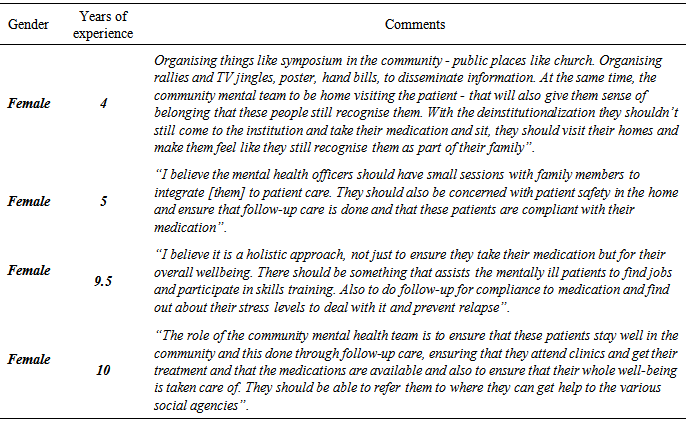

- The findings of the study are presented in two parts: firstly demographics, and secondly by the research objectives.There were 17 (77.2%) female and 5 (23%) male participants. The ages of participants ranged from 24 to 55 years. The Psychiatric workers experiences were between one year and four months and twenty five years. The majority (46%) of the respondents had between 6 and 11 years experiences working within the psychiatry settings. The main themes that emerged from the findings were: family bonding; stigma and discrimination; community reaction or unpreparedness; preference towards hospitalized care regression of patients; inadequate community resources; absence and noncompliance with medication; caregivers’ coping mechanism; benefits of institutionalized care and mental health officers’ roles. Psychiatric workers perceived deinstitutionalization to have both negative and positive consequences for the mentally ill patient. Examples of the positive and negative responses that psychiatric workers held towards deinstitutionalization see Table 1.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The intent of the study was to elicit the perceptions psychiatric workers have towards deinstitutionalized care for persons with mental illness. More female workers were represented in this study which is not unusual in the health system. The majority (45.4%) of the psychiatric workers were between 36 and 45 years old. The combined experiences of the psychiatric health workers at the two hospitals amounted to 217 years. Each hospital had 164 years and 53 years respectively. Therefore, the perceptions of these workers are respected and should be taken into consideration in any decision about deinstitutionalization. Mental Health workers from both hospitals gave both negative and positive perceptions about deinstitutionalization. The negative perceptions clustered around community receptiveness to have persons diagnosed with mental illness readmitted into their communities; also the advantages that mentally ill patients have when they are nursed in a hospitalized setting. The therapeutic nature of the hospital, the adherence to treatment and knowledge of the staff to care for the hospitalized patient were emphasized. Many of these workers have been accustomed to caring for patients in hospital where they have authority and control over the schedule of the patients. The possibility of losing control could appear disconcerting and influence the perception that was held about institutionalized versus deinstitutionalized care. The psychiatric workers see it as their right to be the custodian of the mentally ill patients care hence they questioned the ability of families and communities to relieve them of those duties. This finding is consistent with other findings on institutionalized services Hickling (2011), and inconsistent with caregivers (Pusey-Murray and colleagues, 2010).The Psychiatric workers gave views pertaining to care of the mentally ill in the community. Their main concerns evolved around the lack of human and material resources to continue treatment also the lack of community education in that persons need to gain adequate understanding of the nature of mental illness and to ensure that patients are accepted and cared for effectively. The Psychiatric workers expressed apprehension about the availability of medications to prevent patients from reverting to the acute stage of their illness. Another misgiving that the workers had was the knowledge that family members and caregivers possess to achieve compliance with medication and follow-up appointments. The concerns of the workers are valid because if patients return to their respective communities without the necessary resources and support systems in place the basic tenets of deinstitutionalization will be destabilized. Pusey-Murray and Miller (2013) found that although caregivers recognized the importance of and valued social interaction with family members and the community, both for the mentally ill and themselves there were problems associated with cost, accessibility and availability of medications. Negative attitudes, stereotypes and discrimination are still prevalent with mentally ill patients (Hansson & Markström 2014). Stigma and discrimination continue to be deterrent to deinstitutionalized services. Hickling and Gibson (2012) found these variables still exist in society. Stigma and discrimination of persons with mental illness add to the burden of living with a mental illness. One would have hoped that with the increased thrust of the Ministry of Health towards deinstitutionalized care more effort would be made to address this on a national scale. A concerted effort must be made towards educating the public. Jamaica is not the only country that has embarked on deinstitutionalized care therefore lessons can be learned from those who are successful. The study could serve as a basis for a future island-wide study inclusive of general hospitals and community health centers.

5. Conclusions

- The study demonstrates that psychiatric workers hold views that are noteworthy about the care that mentally ill patients should receive and perceive themselves as guardians of psychiatric care. It is obvious that they have given much thought about the factors that facilitate and hinder deinstitutionalization. Both negative and positive views about institutionalized and deinstitutionalized care were vividly expressed. It would be instructive for decision makers to include the perceptions of the workers in charting the path towards successful deinstitutionalization. The findings can also be used to heighten the awareness of communities regarding rehabilitation issues of persons with mental illnesses after they have been stabilized in hospital. Measures to improve resources to sustain the mental health of patients, allowing them to remain with their families and to be more productive in society should be taken.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- This project was supported by a grant from the School of Graduate Studies, Research and Entrepreneurship, University of Technology, Jamaica. We acknowledge the contribution of Mrs. Alta Mowatt in assisting with the data collection.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML