-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

International Journal of Nursing Science

p-ISSN: 2167-7441 e-ISSN: 2167-745X

2014; 4(1): 1-10

doi:10.5923/j.nursing.20140401.01

Effect of Implementing Clinical Pathway on the Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Aida Faried Abd-Elwanees1, Azza Hamdi El-Soussi2, Sahar Younes Othman1, Raed Elmetwaly Ali3

1Mansoura University, Faculty of Nursing, Mansoura, Egypt, Critical Care and Emergency Nursing

2Alexandria University, Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria, Egypt, Critical Care and Emergency Nursing

3Mansoura University, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura Egypt, Pulmonary Medicine

Correspondence to: Sahar Younes Othman, Mansoura University, Faculty of Nursing, Mansoura, Egypt, Critical Care and Emergency Nursing.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2012 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) represent a major burden for patients and health care systems. It results in increased patient mortality, length of hospital stay, and healthcare costs. The clinical pathway for hospitalized patients suffering from AECOPD is poorly established, although a clinical pathway is an integral part of total quality management. Hence, the aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of implementing a clinical pathway on the clinical outcomes in the management of patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A quasi experimental research design was utilized during the current study and it was conducted on 60 adult patients at the Respiratory Intensive Care Unit of Mansoura Main University Hospital. The patients were divided into two groups (control and study group) 30 patients in each. The control group: non-clinical pathway group non-CP group involved patients receiving the routine management regimen while the study group: clinical pathway group CP group involved patients who received management according to the clinical pathway. Clinical outcomes were evaluated by comparing the length of ICU stay, dyspnea level, anxiety level, pulmonary function tests and ABG values. The findings of this study revealed that patients in the CP group had significantly shorter length of stay than the non-CP group with mean 4.73 day versus 7.83 day p= 0.00.The mean dyspnea score declined from admission to discharge for the CP group from (8.2±1.6) to (0.4± 0.5) compared with (7.9±1.7) to (3.1±1.3) for the non-CP group. On discharge the differences between the two groups were statistically significant p=0.00. Also the mean anxiety score significantly decreased from admission to discharge for the CP group from (3±0.0) to (1.1± 3.0) compared with (2.9± 0.18) to (2.2±0.6) for the non-CP group p=0.00. Moreover, there was a significance difference between the CP group and non-CP group on discharge regarding pulmonary function tests and ABG values. The findings indicated that COPD patients with acute exacerbations can be effectively managed using a clinical pathway. The established pathway achieved its goal of decreasing patient's length of stay, improving dyspnea and anxiety levels, improving pulmonary function test and improving the arterial blood gases.

Keywords: Acute Exacerbation of COPD, Pulmonary Rehabilitation, Clinical Pathway, and Clinical Outcomes

Cite this paper: Aida Faried Abd-Elwanees, Azza Hamdi El-Soussi, Sahar Younes Othman, Raed Elmetwaly Ali, Effect of Implementing Clinical Pathway on the Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, International Journal of Nursing Science, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2014, pp. 1-10. doi: 10.5923/j.nursing.20140401.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) is one of the most common causes of hospital admissions. These hospital admissions come with a high mortality rate particularly in those requiring ventilator support. AECOPD represents an extremely severe event that can occur at any point during the long course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). It can be lethal and can impair a patient’s health-related quality of life severely and permanently[1,2,3 ]. It is estimated that approximately 210 million people worldwide have COPD, and its incidence is believed to be rising. Mortality predictions suggest that COPD will become the third leading cause of death in 2020 and the fourth leading cause of death in 2030[2,4,5]. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are characterized by increased dyspnea, reduced quality of life and muscle weakness. Depending on the severity of baseline COPD, additional derangements can occur during acute exacerbation, including hypoxemia, worsening hypercapnia, cor-pulmonale with worsening lower extremity edema, or altered mental status and enhanced symptoms of depression and fatigue[6]. Most exacerbations can be managed in the outpatient setting; however, patients with AECOPD causing acute respiratory failure with severe hypoxia or persistent or severe respiratory acidosis, altered mental status, or hemodynamic instability require admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) for management[7]. The main goals of treating patients with AECOPD are to restore the patient to his or her previous stable baseline and to prevent or reduce the likelihood of recurrence. This requires identifying the precipitating factors and reversing or ameliorating it while optimizing gas exchange and improving the patient's symptoms[6].Moreover, AECOPD results in acute muscle deconditioning and weakness. Hence patients with frequent exacerbations have more pronounced skeletal muscle weakness. Pulmonary rehabilitation may improve prognosis in these patients by addressing relevant risk factors for exacerbations such as low exercise capacity[8]. Man et al., 2004 reported that early pulmonary rehabilitation for AECOPD is safe and results in clinically significant improvements in exercise capacity and health status of patients. It can be considered as soon as the vital signs of patients are stabilized, even if they are requiring life support to maintain this stability[10].Nurse-led care for patients, who were hospitalized with an acute exacerbation, including pulmonary rehabilitation, self-management education and an action plan, resulted in reduced mortality rates. It has been established that treatment plans incorporating, for example, individualized diet and exercise programs; education around pharmacotherapies, inhalation techniques and relaxation practices, can improve the mental and physical well-being of AECOPD patients [11].Now healthcare is changing towards more patient focused care and the organization of the care process is one of the main areas of interest within the next years for clinicians and health care managers. A main method to reorganize a care process is the development and implementation of a clinical pathway (CP)[12]. Randomized controlled trials, evidence - based medicine, clinical guidelines, and total quality management are some of the approaches used to render science-based health care services. CP is a document outlining a standardized, evidence-based multidisciplinary management plan, which identifies the appropriate sequence of clinical interventions, timeframes and expected outcomes for a homogenous patient group[1].The CP for hospitalized patients suffering from AECOPD is poorly established, although a clinical pathway is an integral part of total quality management. To date, there has been no published study on the effectiveness of AECOPD clinical pathway development and implementation in Egypt and also very few studies worldwide. In view of the positive outcomes reported in the literature in decreased length of stay (LOS) and readmission, the researchers decided to examine the effect of implementing CP on the clinical outcomes of COPD patients with acute exacerbations.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

- A quasi experimental research design was utilized in this study to examine the effect of implementing clinical pathway on the clinical outcomes in the management of patients with AECOPD.

2.2. Setting

- This study was carried out in the Respiratory Intensive Care Unit (RICU) of Mansoura Main University Hospital.

2.3. Subjects

- A convenience sampling method was used during the current study. Sixty adult patients (aged 40 years and above) of both sexes admitted to RICU were included in this study. The sixty patients having an episode of AECOPD and becoming clinically stable; and managed either by conventional oxygen therapy or non invasive mechanical ventilation were included in this study. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a diffuse interstitial lung disease, systemic neurological disease, severe orthopedic problem, cardiovascular instability, use respiratory depressant drugs or intubated & mechanically ventilated on the first day of admission. The patients were divided into two groups (control and study group) 30 patients in each. The control group: non-clinical pathway group "non-CP group" involved patients receiving the routine management regimen while the study group: clinical pathway group "CP group" involved patients who received management according to the developed clinical pathway from admission until discharge.

2.4. Ethical Approval

- All patients or a family member gave a written informed consent and the study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing, Mansoura University.

2.5. Tools

- Two tools were developed by the researchers based on the related literature[7,13-18] and used to collect necessary data about the study subjects.Tool I: Patient's Assessment SheetIt was developed by the researchers in order to record patient's data, physiological and psychological parameters and includes two parts. Part I: Socio-demographic data and baseline characteristics. Part II: physiological and psychological Parameters. Physiological parameters include: pulmonary function test (Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and FEV1/ FVC), arterial blood gases and dyspnea scale (Modified Borg Dyspnea Scale)[14]. The dyspnea scale rates the difficulty of breathing, starts at number 0 where breathing is causing no difficulty at all and number 10 where breathing difficulty is maximal. Psychological parameters include: Hamilton Anxiety Scale[13], this scale consists of 14 items, each defined by a series of symptoms and measures both psychic anxiety and somatic anxiety. Each item is scored on a scale of 0(not present) to 4 (severe), with a scoring system, if it is less than 17 indicates mild severity, 18-24 mild to moderate severity and 25-30 moderate to severe. Tool II: Clinical Pathway Audit Tool It was developed by the researchers after reviewing related literature[19] and it is utilized to evaluate the established AECOPD clinical pathway by the clinical and academic experts. The AECOPD clinical pathway audit tool consists of 14 items. Each item is rated as '' agree'' and '' disagree''.

2.6. Data Collection

- Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the hospital administrative authority. Tools were tested for their reliability and validity. The tools were reviewed by a jury composed of seven experts in the field of critical care nursing and pulmonary critical care medicine for revision of its content validity and clarity. Moreover, the reliability of the tools was estimated using the Cronbach’s Coefficient alpha test. The reliability of the tools showed higher level of internal consistency (>0.85). A pilot study was carried out on 6 patients who met the predetermined selection criteria to assess the feasibility and the applicability of the data collection tools. The patients were divided into two groups (control and study group) 30 patients in each. The first 30 patients was the control group: non-clinical pathway group "non-CP group" involved patients receiving the routine management regimen while the second 30 patients was the study group: clinical pathway group "CP group" involved patients who received management according to the developed clinical pathway from admission until discharge. The study was carried out from June 2010 to April 2012. It was conducted on four phases; observation phase, establishing AECOPD clinical pathway phase, implementation phase and evaluation phase.Phase One:'' Observation Phase''During this phase, the researcher observed clinical outcomes for non-CP group who received the routine pulmonary care practices provided by critical care nurses in RICU. Patients in this group were followed up by the researcher from the time of enrollment in the study until discharge. Patient's socio-demographic data and baseline characteristics were documented by the researcher in tool one. Moreover, the clinical outcomes of those patients (including ICU LOS of dyspnea level, anxiety level, pulmonary function tests and ABG results) were evaluated during this phase.Phase Two: "AECOPD Clinical Pathway Development"This phase was accomplished by the following steps:Step 1: Selection of the Care Population and Selection of an Expert PanelThe patient population under study was specified as ‘Patients admitted to the RICU with AECOPD. Expert panel was involved in each step of pathway development. This panel was composed of the following: (i) two respiratory professors from faculty of medicine who are specialized in pulmonary care; (ii) two professors in faculty of nursing who have extensive clinical and scientific expertise in development and implementation of clinical pathways; (iii) the head nurse and two staff nurses; (iv) one physiotherapist; (v) one social worker; and (vi) the researchers.Step 2: Literature Review An extensive literature review was conducted by the main researchers to identify all available evidence for management of patients with AECOPD, the following resources were explored: websites of international respiratory societies: European Respiratory Society (ERS) (www.ersnet.org); Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD (GOLD) (www.goldcopd.org); National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (www.nice.org.uk); and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (www.sign.ac. uk). Also it was conducted through several relevant nursing and medical Journals[1,7,17,18,20-23]. Step 3: Formulation of AECOPD Clinical Pathway DraftThe expert panel and researchers met four times over a four weeks period and the pathway was redrafted twice before the final agreed format was ready for piloting on the study group. The AECOPD clinical pathway formulated into three phases including: acute phase (day 1-2), transition phase (day 3-5) and pre-discharge phase (day 6-7). It consists of the following interventions: (1) Day-to-day patients assessment; (2) Treatment regimes including bronchodilator therapy, corticosteroid and antibiotic requirement, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis's, fluid regime; (3) Aeration practices including elevation of the head of the bed greater than 30 degree, chest physiotherapy, administration of humidified oxygen, maintaining adequate hydration and providing nebulizer therapy; (4) Circulation/perfusion practices; (5) Activity practices: (The activity begins from the first day with turning the patient every 2 hours until dangled at bed side, encourage bed rest in high fowler position, then progressed daily as patient's tolerance; (6) Pain control practices; (7) Education practices including purse lip breathing, positioning, relaxation, effective coughing techniques, and exercise & strength building; (8) Nutrition practices including daily assessment of the nutritional status, providing high- protein, high caloric diet offered and divided into 5-6 meals/ day, and providing stress ulcer prophylaxis; (9) Discharge planning including smoking cessation, influenza and pneumococcal vaccination, diet and life style changes, medications, equipment used at home, how to use an oral inhaler or oxygen therapy at home and how to recognize symptoms of exacerbations. Finally, coordination with social worker was performed to assess for support if patient has no access to financial or community support. Moreover, the AECOPD clinical pathway includes expected daily outcomes (stabilization of vital signs, improvement of dyspnea & anxiety levels, maintaining adequate oxygenation, ensuring clear breath sounds, balanced intake and output, optimal GIT function, adequate pain control and patients remained safe from harm. Additionally, the AECOPD clinical pathway includes variance tracking record which allows the deviations to be documented and analyzed daily from the first day until discharge. Analysis of variance informs clinicians of patients’ immediate needs. It also includes what occurred, why and what was done about it. Step 4: Evaluating of Content ValidityContent validity of the AECOPD clinical pathway was evaluated and examined by 15 academic and clinical experts using tool II.Step 5: Piloting A pilot study was carried out to evaluate the feasibility of the AECOPD clinical pathway and to modify the pathway accordingly. Step 6: Formulation of Dissemination and Implementation StrategySeparate sessions for nursing staff (10 nurses) to introduce the AECOPD clinical pathway were scheduled over a four weeks period to explain the pathway in brief and outline the main roles to be played by each one.Phase Three: "AECOPD Clinical Pathway Implementation"During this phase, the developed AECOPD clinical pathway was applied to the study group (CP group) for approximately six months started in June 2009. A multidisciplinary team composed of 10 nurses and 4 physicians was formulated to help in the implementation of AECOPD clinical pathway for the study group. Patients admitted to the RICU with a diagnosis of AECOPD were screened within 24 hours of admission and managed according to the AECOPD clinical pathway if the patients fulfilled the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The established pathway was implemented by the trained nurses and the researcher daily in three shifts in RICU until patient discharge. The expected daily outcomes were assessed daily from admission until discharge. Variances affecting the adherence to the developed pathway were monitored, analyzed, recorded, and a plan was developed to overcome them. Phase Four: "Evaluation Phase"This phase consisted of comparing the outcomes for both groups (non-CP group and CP group) including: length of ICU stay (ICU LOS), dyspnea level, anxiety level, pulmonary function tests and ABG values.Statistical analysisThe collected data were organized, tabulated and statistically analyzed using the statistical package for social studies (SPSS) version 15. Variables were presented as number and percentage and differences between non-CP group and CP group were compared using chi square test. For variables with 2X2 categories where chi square was not suitable for the presence of small observations with expected values less than 5, Fisher exact test was used instead. For other variables with more than more than 2X2 categories, Monte Carol test was used. The level of significance was adopted at p<0.05. For comparing the admission variables versus discharge variables on the same groups whether non-CP group and CP group the paired t test is used. The independent t test is used for comparing variables between the non-CP group and CP group.

3. Results

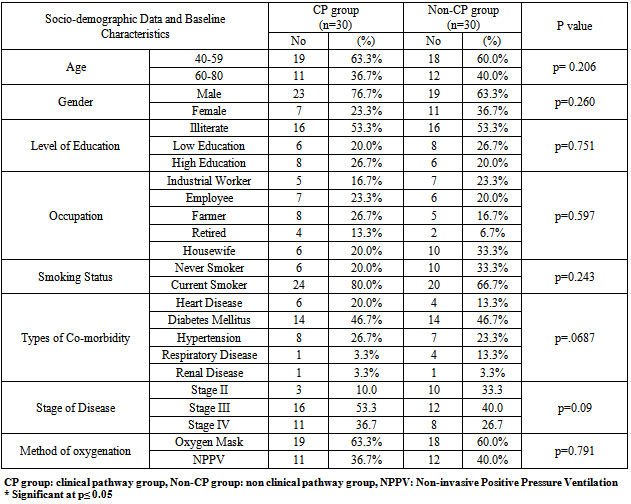

3.1. Socio-demographic Data and Baseline Characteristics

- Table[1] illustrates socio-demographic data and baseline characteristics of the non-CP group and CP group. The basic demographic distributions between the two groups were comparable and no significant differences were noted in age, gender, level of education and occupation. Next the baseline characteristics of smoking status, COPD stage, co-morbidities and method of oxygenation were examined and no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were noted between the two groups.

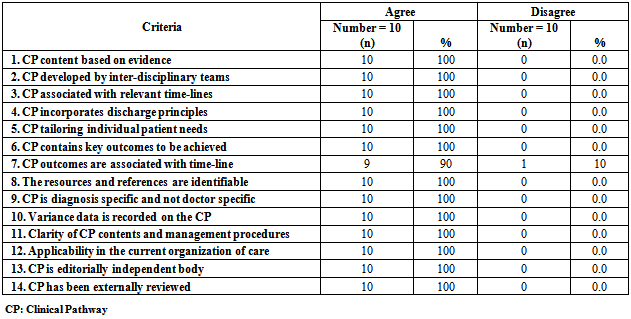

3.2. Clinical Pathway Audit Tool Evaluation Criteria

- Table[2] demonstrates clinical pathway audit evaluation criteria. These results were collected after the establishment of the AECOPD clinical pathway and before its implementation for the study group. It was revised by 10 experts in the field of critical care nursing and pulmonary critical care medicine. It was noticed that (100%) of the audits agreed with all criteria of the established AECOPD clinical pathway except one criteria was accepted by (90%) of the audits which relates to the time-line of the clinical pathway's outcomes.

3.3. Outcomes of Implementing AECOPD Clinical Pathway

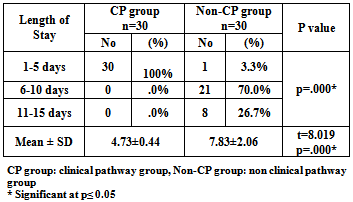

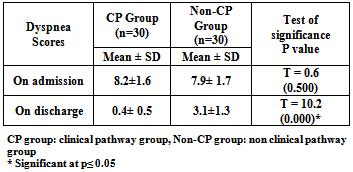

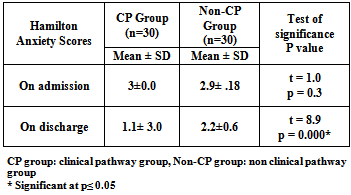

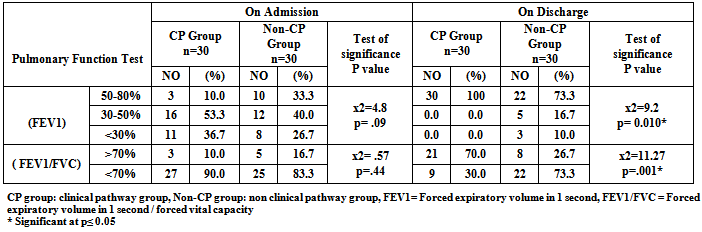

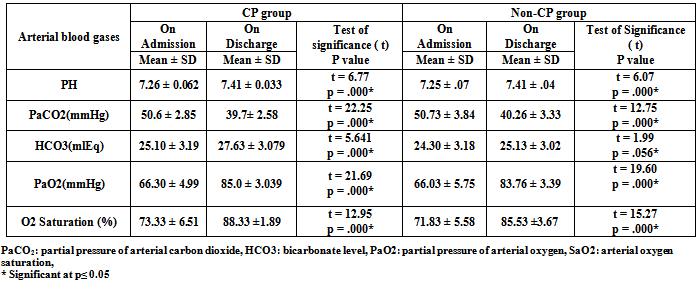

- Table[3] shows comparison between CP and non-CP groups regarding length of stay in RICU. The results of the current study revealed that the overall LOS ranged from 2 to 15 days. All patients (100%) of CP group stayed in RICU from (1-5) days while the majority (70%) of non-CP group stayed in RICU from (6-10) days. The mean LOS of patients managed by the clinical pathway was 4.73±0.44 day compared to 7.83±2.06 day for the non-CP group who were managed according to the unit's routine care. It can be noted from the same table that the T-test reflects highly significant differences between the CP and non-CP groups in relation to RICU LOS p=0.00. Concerning dyspnea score, it was found that the average mean of dyspnea score on admission was (8.2±1.6) and (7.9±1.7) for the CP and non-CP groups respectively with no significance difference between the two groups. On discharge, the results of the present study revealed a significant decline in dyspnea score among patients in the both groups. It represents (0.4± 0.5) and (3.1±1.3) for the CP and non-CP groups respectively. It can be noted that the level of reduction in the CP group was higher than its level in the non-CP group. Table[4]Regarding Hamilton Anxiety Score, it was observed that the average mean of Hamilton Anxiety Score on admission was (3±0.0) for the CP group and (2.9± 0.18) for the non-CP group with no significance difference between the two groups. On the other hand, on discharge the mean value of Hamilton Anxiety Score was significantly reduced to be (1.1± 3.0) for the patients managed by the clinical pathway (CP group) and (2.2±0.6) for the non-CP group. Also we can detect that the level of reduction in the CP group was higher than its level in the non-CP group. Table[5]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- In the past decade, critical care nurses have witnessed an increased interest in improving outcomes for critically ill patients and there has been a surge of interest in the use of evidence based protocols and care pathways in clinical practice[24]. It is important that critical care nurses contribute to the development of such clinical pathway in order to actively shape their own practice. In response to this the current study was performed to investigate the outcomes of implementing AECOPD clinical pathway. The current clinical pathway was developed by multidisciplinary group involved member from different disciplines including; critical care nursing, pulmonary critical care medicine, academic and respiratory intensive care clinicians, because the need to provide efficient care requires the collaboration of all disciplines involved in providing care for critically ill patients. The current clinical pathway was evaluated by external audits to ensure content validity, clarity, and applicability by group experts from different categories. The advantages of using expert group to evaluate clinical pathway include sharing of work among group members, reduced potential for bias in the evaluation process, and increased awareness of the developed clinical pathway. The results of audits' evaluation of the current pathway demonstrated that the overall pathway audit criteria were met and they were strongly agreeing its application in clinical practice. The researchers developed and implemented a clinical pathway for the management of patients with AECOPD, and compared the outcomes (LOS, anxiety level, dyspnea level, pulmonary function test and arterial blood gases) of patients managed with the pathway (CP group) with patients managed by the routine pulmonary care practices provided by the critical care nurses (non-CP group). As a baseline for comparison, the non-CP group was comparable to the patients in the CP group: both groups had similar access to drugs, pulmonary care and ICU services; and their demographic profiles were similar. There are no any significant differences in the age, gender, and others demographic and baseline characteristics between the two groups.Regarding length of stay, the results of the current study confirmed our hypothesis that usage of clinical pathway in the management of patients with AECOPD significantly decreased the RICU LOS for the CP group as compared to the non-CP group. It was found that the mean LOS of patients managed by the clinical pathway was 4.7 day compared to 7.8 day for the non-CP group who were managed according to the unit's routine care. These shorter durations in the CP group may be attributed to the fact that the subjects in this group were approached by the established pathway. The utilization of such approach optimizing patient care process, sequencing and timing interventions by multidisciplinary critical care professionals in orders to achieve the desired outcomes. Also, there was a clear discharge plan listed in the clinical pathway. Therefore, this pathway allowed improving the quality of care while keeping hospital length of stay to an acceptable minimum time through early recognition and interventions of medical complications, nursing or social problems that necessitate prolonged hospitalization period. These factors may have contributed to a shorter ICU LOS.On the other hand, patients in the non-CP group were handled by the unit's routine care. There were no structured guidelines or protocols kept in place for the non-CP group. Thus, the use of such approach led to unnecessary prolongation of ICU LOS among this group of patients. This could be attributed to the relative increase in the number and duration of complications suffered by this group of patients. The results of the current study are in agreement with Ban et al., 2012[2], who found a significant reduction in LOS of the CP group as compared to the non-clinical pathway group. The median LOS in non-CP group was 7 days whereas the LOS in CP group was 5 days. Furthermore, a study by Celis et al., 2012[7], which utilized the COPD clinical pathway, also showed a significant reduction of mean hospital stay of 13.21 days in the control group and 10.24 days in the clinical pathway group. In contrast to previous reports and the results of the present study, Nishimura et al., 2011[1] found that there is a longer LOS where the average LOS was 20.3 days, and the median value was 15 days. He mentioned that longer LOS is mainly due to complications and this difference can be attributed to the different systems of health care delivery and different complications. In relation to dyspnea level, there was a strong association of the presence of dyspnea and severity of AECOPD where the increased dyspnea is one of the three cardinal symptoms of the COPD exacerbation and dyspnea control is one of the first line of management of AECOPD patients. The current study explained that patients in the CP and non-CP groups were almost equally distributed regarding dyspnea score and no significant differences were found between them on admission. Also the current study showed that there was a significant improvement of the dyspnea score among the patients in the CP group as compared to the non-CP group. Where the mean dyspnea score for the CP group decreased from 8.2 to 0.4 while for the non-CP group decreased from 7.9 to 3.1. The improvement of the dyspnea score among CP group was due to the subjects in this group were approached by the clinical pathway where it effectively manages dyspnea by pulmonary rehabilitation practices. On the other hand, patients in the non-CP group were not handled by the clinical pathway. These results are in agreement with the findings Nava, 1998[25], who suggested that dyspnea scores improved in both groups, but the improvement was more marked in group A (received pulmonary rehabilitation) than in group B (received routine medical therapy). Also Paz-Díaz et al., 2007[26], shows that in patients with severe COPD, pulmonary rehabilitation induces independent changes in dyspnea and health-related quality-of-life, where dyspnea measured by the MRC scale was significantly better in the pulmonary rehabilitation group.Concerning anxiety level, anxiety is experienced with depression in the majority of the patients with AECOPD and there was a dynamic relation between dyspnea and emotional functioning, specifically anxiety. Anxiety was seen not as the underlying cause of distressing dyspnea, but as a sign of longstanding or acute respiratory failure.In the current study on comparing the CP and non-CP groups regarding anxiety level, both groups were almost equally distributed and no significance differences were found between them on admission. While there was a reduction of anxiety level on discharge for the both groups and the level of reduction in the CP group was higher than its level in the non-CP group. Where the anxiety level decreased from (severe to mild severity) for the CP group while the anxiety level decreased from (severe to moderate severity) for the non-CP group. The improvement of anxiety level for the CP group may be due to the application of the clinical pathway which involved pulmonary and psychological rehabilitation practices. This pathway contains psychological care and educational aspects concerning anxiety experience. On the contrast the non-CP group received unit's routine care without focusing on patient's psychological problems. These results are in agreement with Güell et al., 2006[27], who revealed in the psychological testing an improvement in personality styles, attitudes, and ability to cope with the disease, together with reductions in depression and anxiety, following the pulmonary rehabilitation program for severe COPD. Also, Tselebis et al., 2013[28], mentioned that pulmonary rehabilitation programs should be offered to all COPD patients irrespective of disease severity, since they all lead to improvement in anxiety and depressive symptoms. Also statistically significant reduction in anxiety and depression was revealed at all stages of COPD. Moreover Withers et al., 1999[29], revealed that pulmonary rehabilitation produced statistically significant falls in mean Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale. Pulmonary rehabilitation also reduced the number of patients with significant anxiety or depression and anxious patients showed statistically greater improvements in exercise capacity following pulmonary rehabilitation. Furthermore, Garuti et al., 2003[30], explained that pulmonary rehabilitation may improve levels of anxiety and depression as well as symptoms, exercise capacity and health related quality of life in moderate to severe COPD patients after an acute exacerbation, where the total percentage of patients with abnormal anxiety score changed (from 31% to 21%) after inpatient pulmonary rehabilitation. Contrary to the previous results and the current results, Coventry, 2009[31], revealed that pulmonary rehabilitation appears to improve anxiety and depression in rehabilitating COPD patients with less favorable psychosocial health, but its efficacy for treating more severe and enduring anxiety and depression is largely unproven. As regards to pulmonary function test as an indicator of clinical outcomes, the current study documents that the majority of the whole patients in the CP and non-CP groups had low Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1) on admission. It was between 30% -50% (which indicated severe stage of COPD) while on discharge the FEV1 improved to 50% -80% (which indicated moderate severity of COPD) on both groups but the level of improvement in patients of the CP group was greater than those in the non-CP group. Moreover, the present study reveals that on admission, the majority of patients in the CP and non-CP groups had low Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second / Forced Vital Capacity (FEV1/FVC) <70% (which indicated moderate severity of COPD). While on discharge, FEV1 /FVC was elevated to >70% (which indicated mild severity of COPD) on both groups but the level of improvement in patients of the CP group was greater than those in the non-CP group.These results are in agreement with the findings of Donaldson, 2002[32]; Ernerman and Cydulka, 1994[33], they reported that the pretreatment FEV1 was low percent and the post treatment FEV1 was little high percent also they mentioned that forty-three percent of the patients had an improvement in pulmonary function of at least twenty percent following treatment. Also Nishimura et al., 2011[1], mentioned that the spirometry performed before discharge revealed that the FEV1/FVC was over 70%. As regards to arterial blood gases, the current study documents that there was no significance difference in arterial blood gases between CP and non-CP groups on admission. In relation to the mean value of PaCO2 among the study and control groups, the values declined on the both groups from respiratory acidosis to normal acidity. Also the mean value of PaO2 was relatively improved among patients in the CP and non-CP groups from admission to discharge. As regards arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2), the present study was reported that the mean values of (SaO2) for the CP and non-CP groups were insignificantly increased from admission to discharge. Finally these results are in agreement with the findings of Nava, 1998[25] who reported that in both groups there was a significant difference in PaCO2 recorded at discharge, also Nishimura et al., 2011[1], mentioned that exacerbated patients presented with high mean value of PaCO2 and low mean value of PaO2 on admission.

5. Conclusions

- The findings indicated that COPD patients with acute exacerbations can be effectively managed using a clinical pathway. The established pathway during the current study achieved its goal of decreasing patient's length of stay, improving dyspnea and anxiety levels, improving pulmonary function test and improving the arterial blood gases.

6. Recommendations

- Based on The findings of this study, the following recommendations are suggested:§ Clinical pathway should be implemented routinely for COPD patients with acute exacerbations.§ Establishment of pulmonary rehabilitation unit attached to the respiratory intensive care unit. § All COPD patients and their family should receive adequate knowledge and skills regarding management of COPD and its exacerbations.§ Nurses should be encouraged to collaborate with the other health members to provide a comprehensive holistic care for the patients with AECOPD utilizing the clinical pathway.§ Integrating AECOPD clinical pathway into plan of care to replace the traditional nursing care plan.§ Conducting training program for health care providers on the AECOPD clinical pathway implementation for better quality of care.§ The study can be replicated on a larger sample selected from different geographical area in Egypt.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML